Decoding Disease Through Metabolic Networks: From Systems Biology to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how metabolic networks are reconstructed, analyzed, and applied to understand complex human diseases.

Decoding Disease Through Metabolic Networks: From Systems Biology to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how metabolic networks are reconstructed, analyzed, and applied to understand complex human diseases. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of metabolic imbalance in conditions like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and Crohn's disease. The content details cutting-edge computational methodologies including genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) and flux balance analysis (FBA) for simulating disease states. It further addresses challenges in model curation and validation, compares metabolic states between healthy and diseased conditions, and highlights emerging applications for biomarker discovery and identifying novel therapeutic targets. The synthesis offers a roadmap for leveraging metabolic network analysis to advance personalized medicine and drug development.

The Architecture of Life: How Metabolic Networks Underlie Health and Disease

Metabolic networks are comprehensive, structured assemblies of biochemical reactions that enable cells to convert nutrients into energy, synthesize essential building blocks, and eliminate waste products. These networks represent a fundamental bridge between genetic information and cellular phenotype, orchestrating the biochemical processes that sustain life. In the context of disease research, understanding metabolic networks is paramount, as pathological states often arise from, or result in, significant reprogramming of these core biochemical circuits. The systematic study of these networks through genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) provides a computational framework to simulate metabolism and predict cellular behavior under various conditions, offering powerful insights into disease mechanisms [1]. Alterations in metabolic network function serve as critical drivers in numerous diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and inflammatory conditions, making them a prime target for therapeutic intervention [2] [3].

Core Principles of Metabolic Network Biology

Architectural Components and Hierarchical Organization

Metabolic networks are intrinsically hierarchical, operating across multiple interconnected levels. At the most fundamental intracellular level, metabolism encompasses the conversion of nutrients into energy (ATP) and biosynthetic precursors through pathways involving glucose, lipids, and amino acids [2]. These intracellular processes do not operate in isolation; they are coordinated through intercellular metabolic interactions where different cell types—such as neurons, glial cells, and endothelial cells—exchange substances and metabolites to maintain tissue homeostasis [2]. Finally, at the highest level of organization, the metabolic microenvironment emerges from the collective interactions between cells and their surroundings, which can become profoundly remodeled in disease states like glioblastoma, where tumor cells "domesticate" their microenvironment to support growth and immune evasion [2].

This hierarchical organization is mirrored in computational representations of metabolism. The two-level representation used in systems biology distinguishes between a structural level (depicting pathways as nodes and their relationships as edges) and a functional level (representing the specific reaction content within each pathway) [4]. This modular approach enables both local analysis of specific metabolic functions and global comparison of entire metabolic networks across different organisms or conditions [4].

Key Functional Properties and Network Dynamics

Metabolic networks exhibit several defining characteristics that govern their functional capabilities. Metabolic reprogramming represents a fundamental property wherein cells alter their metabolic flux patterns in response to changing conditions or disease states. For instance, cancer cells frequently exhibit the "Warburg effect," preferentially generating energy through aerobic glycolysis rather than mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation even in oxygen-rich environments [2]. This metabolic flexibility is enabled by intercorrelation between metabolites, where molecules from common enzymatic pathways or origins demonstrate high degrees of coordination, creating complex regulatory dynamics that can vary substantially between healthy and diseased states [5].

The dynamic regulation of metabolic networks allows cells to prioritize different metabolic outcomes based on physiological demands. A striking example is the fate of pyruvate, a central metabolic node: its diversion into mitochondrial energy production versus cytosolic biosynthesis can directly control fundamental cellular properties like cell size, demonstrating how metabolic decisions can override conventional signaling pathways to dictate cellular physiology [6].

Metabolic Network Alterations in Disease Pathogenesis

Cancer Metabolic Rewiring

Cancer cells extensively reprogram their metabolic networks to support rapid proliferation and survival in challenging microenvironments. A seminal study revealed a surprising connection between the mitochondrial enzyme succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) and purine synthesis, a process essential for DNA production in proliferating cells [7]. When SDH is inhibited, succinate accumulation interferes with the enzyme SHMT2, stalling purine production. Cancer cells counter this limitation by activating a backup purine salvage pathway to recycle old purines, revealing a metabolic vulnerability that can be therapeutically exploited through dual inhibition of both SDH and the salvage pathway [7].

Table 1: Key Metabolic Alterations in Cancer Cells

| Metabolic Process | Normal Function | Cancer Alteration | Therapeutic Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purine Synthesis | Controlled nucleotide production for DNA/RNA | Becomes dependent on salvage pathways when de novo synthesis is impaired | Combined inhibition of SDH and purine salvage pathway shows anti-tumor effects [7] |

| Glucose Metabolism | ATP production via oxidative phosphorylation | Preferential use of aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect) | Creates acidic microenvironment that promotes invasion and treatment resistance [2] |

| Pyruvate Fate | Balanced between energy production and biosynthesis | Altered mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC) expression | MPC downregulation increases cell size; manipulation affects tumor growth [6] |

Neurodegenerative and Brain Disorders

The brain's exceptionally high metabolic demand—consuming 20-25% of the body's oxygen at rest—makes it particularly vulnerable to metabolic disturbances [2]. In Alzheimer's disease, endothelial metabolic dysfunction reduces glucose supply to critical regions like the hippocampus and frontal cortex, impairing neuronal energy metabolism and promoting pathological protein aggregation [2]. Parkinson's disease features mitochondrial dysfunction and elevated oxidative stress that disrupt neuronal metabolism, reducing ATP production and facilitating α-synuclein aggregation [2]. These chronic deficits contrast with the acute metabolic collapse observed in ischemic stroke, where disrupted glucose and oxygen supply rapidly impair energy production, leading to ionic imbalance, oxidative stress, and widespread cell death [2].

Inflammatory and Metabolic Diseases

Metabolic network analysis has revealed profound alterations in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), where the construction of cell-type-specific metabolic models of colonic epithelial cells (iColonEpithelium) has identified distinct changes in nucleotide interconversion, fatty acid synthesis, and tryptophan metabolism in both Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis [1]. More broadly, metabolic phenotypes—comprehensive characterizations of an individual's metabolites—precisely reflect interactions between genetic background, environment, lifestyle, and gut microbiome, serving as molecular bridges between healthy homeostasis and disease-related metabolic disruption [3].

Methodologies for Metabolic Network Research

Genome-Scale Metabolic Reconstruction

The construction of high-quality, genome-scale metabolic reconstructions represents a foundational methodology in metabolic network research. This process transforms genomic and biochemical information into structured knowledge-bases that can be converted into mathematical models for computational analysis [8]. The reconstruction pipeline proceeds through four major stages: (1) creating a draft reconstruction from genomic annotations and biochemical databases; (2) manual refinement and network gap identification; (3) conversion to a mathematical model; and (4) network validation and debugging [8]. For well-studied organisms, this process can take 6-24 months and requires integration of diverse data types, including genome sequence, biochemical pathways, and physiological information.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Metabolic Network Reconstruction

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Databases | Comprehensive Microbial Resource (CMR), Genomes OnLine Database (GOLD), NCBI Entrez Gene | Provide annotated genome sequences for identifying metabolic genes [8] |

| Biochemical Databases | KEGG, BRENDA, Transport DB | Offer curated information on biochemical reactions, enzyme functions, and metabolite transport [8] |

| Organism-Specific Databases | Ecocyc, Gene Cards, PyloriGene | Supply specialized metabolic information tailored to specific model organisms [8] |

| Reconstruction Software | COBRA Toolbox, CellNetAnalyzer, Simpheny | Enable computational construction, simulation, and analysis of metabolic network models [8] |

| Chemical Databases | PubChem, pKa databases | Provide physicochemical properties of metabolites essential for modeling reaction thermodynamics [8] |

Experimental Modulation of Metabolic Pathways

CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing has emerged as a powerful tool for experimentally validating metabolic network predictions. For instance, to investigate the role of SDH in purine metabolism, researchers used CRISPR-Cas9 to knock out the SDH enzyme in cells, confirming that its loss impaired de novo purine synthesis and forced reliance on salvage pathways [7]. This approach can be combined with chemical inhibitors to achieve dual metabolic targeting, such as simultaneously inhibiting both SDH and the purine salvage pathway to synergistically decrease tumor growth [7].

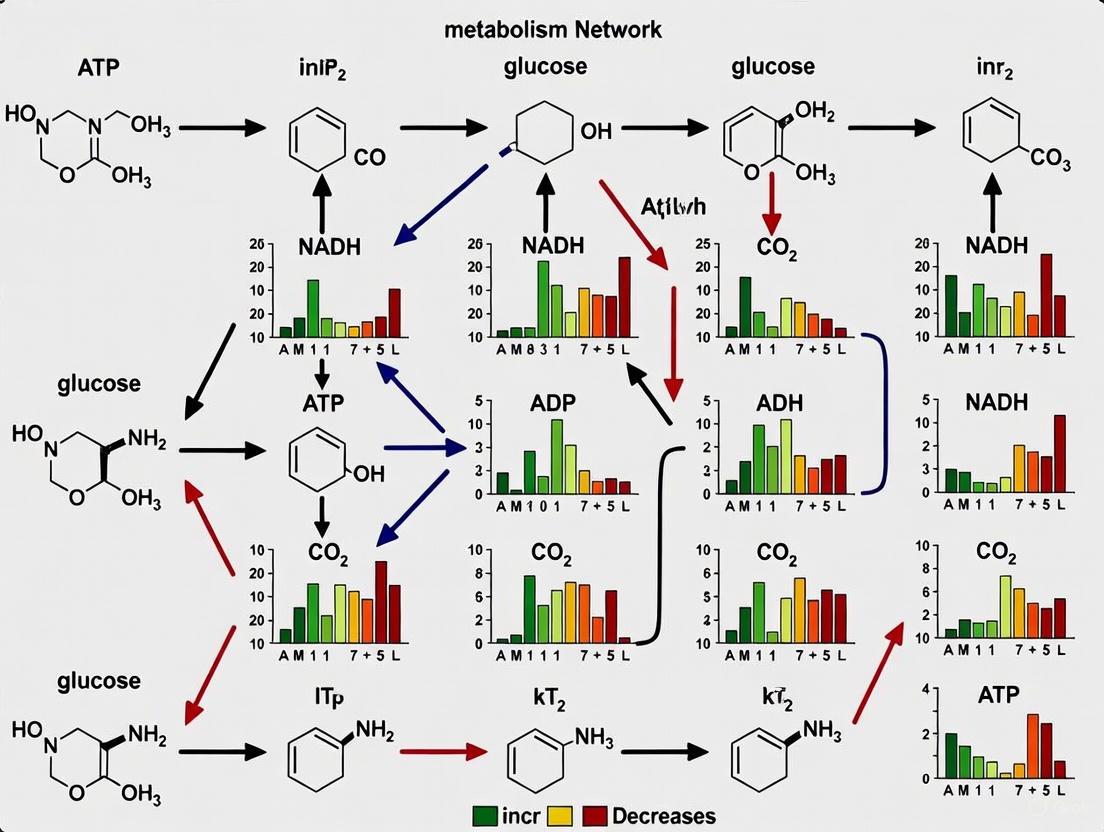

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for investigating metabolic networks using genetic and chemical approaches:

Statistical Analysis of Metabolomics Data

Advanced statistical methods are essential for analyzing high-dimensional metabolomics data. With emerging technologies now capable of profiling thousands of metabolites, researchers must select appropriate analytical approaches based on study design and data characteristics [5]. Sparse multivariate methods like sparse partial least squares (SPLS) and least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) generally outperform traditional univariate approaches, especially in nontargeted metabolomics datasets where the number of metabolites exceeds or approaches the number of study subjects [5]. These methods demonstrate greater selectivity and lower potential for spurious relationships in high-dimensional data, making them particularly valuable for biomarker discovery and pathway analysis in disease research.

Visualization and Interpretation of Metabolic Networks

The complexity of metabolic networks presents significant visualization challenges. Conventional network layout algorithms often sacrifice low-level details to maintain high-level information, complicating the interpretation of large biochemical systems like human metabolic pathways [9]. Innovative approaches like Metabopolis address this problem by adapting concepts from urban planning, creating visual hierarchies where biological pathways are analogous to city blocks and grid-like road networks [9]. This method partitions the map domain into semantic sub-networks, bundles long edges to reduce clutter, and maintains simultaneous global and local context—enabling visualization of entire metabolic networks like human metabolism with unprecedented clarity [9].

Tools like MetNet further facilitate metabolic network analysis through two-level representation and comparison capabilities. This approach allows researchers to automatically reconstruct metabolic networks from KEGG database information, compare networks across different organisms or conditions, and visualize both structural similarities and functional differences [4]. Such visualization capabilities are crucial for identifying metabolic signatures associated with disease states and understanding how specific pathway alterations contribute to pathological processes.

Therapeutic Applications and Future Directions

The therapeutic targeting of dysregulated metabolic networks represents a promising frontier in drug development. The systematic identification of metabolic vulnerabilities—such as the compensatory purine salvage pathway activated when SDH is inhibited—enables rational design of combination therapies that simultaneously block multiple metabolic adaptations [7]. This approach demonstrates how understanding network-level metabolic compensation can reveal synergistic therapeutic strategies with potent anti-tumor effects.

Future research directions will increasingly focus on multi-omics integration, combining metabolomic data with genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic information to build more comprehensive models of metabolic regulation in health and disease [3]. The application of artificial intelligence and big data mining to metabolic phenotypes will further enhance our ability to identify complete regulatory networks, advancing early diagnosis, precise prevention, and targeted treatment strategies [3]. Additionally, the development of more sophisticated cell-type-specific metabolic models like iColonEpithelium will enable deeper investigation into tissue-specific metabolic alterations in disease and facilitate exploration of host-microbiome metabolic interactions [1].

The continued refinement of metabolic network analysis promises to catalyze a paradigm shift in medicine—from treating disease symptoms to targeting underlying metabolic dysfunction, ultimately advancing a more preventive and personalized approach to healthcare.

Metabolic networks represent complex systems of biochemical interactions that convert nutrients into energy and essential biomolecules. Growing evidence from systems biology reveals that the pathogenesis of diverse chronic disorders—including cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, and metabolic diseases—stems from fundamental dysregulation within these metabolic networks [10]. Rather than isolated molecular defects, these conditions exhibit system-wide disturbances in metabolic flux, compartmentalization, and cross-tissue communication. Modern research approaches now leverage genome-scale metabolic models, spatial covariance mapping, and multi-omics integration to decode these complex network pathologies [11] [12] [13]. This whitepaper synthesizes current mechanistic insights, quantitative evidence, and methodological frameworks for investigating metabolic network imbalances across disease states, providing researchers with advanced tools for mapping disease-specific metabolic rewiring.

Molecular Mechanisms Linking Metabolic Imbalance to Disease Pathogenesis

Core Pathogenic Drivers in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD)

MASLD pathogenesis demonstrates how multiple metabolic disruptions converge to drive disease progression. The condition involves complex interactions between genetic susceptibility, metabolic and endocrine disorders, imbalanced intestinal flora, and disrupted hepatocyte homeostasis [14]. Key mechanisms include:

- Lipid accumulation: Central to MASLD pathogenesis, ectopic fat deposition in hepatocytes initiates endoplasmic reticulum stress, triggering apoptosis and activating immune responses that promote hepatic inflammation [14].

- Hepatocyte homeostasis imbalance: Metabolic overload induces endoplasmic reticulum stress, leading to unfolded protein response activation and ultimately hepatocyte apoptosis [14].

- Hepatic stellate cell activation: Inflammatory signaling from damaged hepatocytes activates stellate cells, driving excessive collagen deposition and liver fibrosis [14].

- Gut-liver axis disruption: Intestinal dysbiosis and increased gut permeability allow microbial products to reach the liver, exacerbating hepatic inflammation through pattern recognition receptor activation [14].

Metabolic-Epigenetic Nexus in Cardiovascular Diseases

Cardiovascular diseases exhibit sophisticated crosstalk between cellular metabolism and epigenetic regulation, creating persistent metabolic memory that drives pathology even after initial triggers resolve [15]. Key mechanisms include:

- Metabolites as epigenetic regulators: Cellular metabolites serve as substrates and cofactors for epigenetic modifications, directly influencing gene expression patterns in cardiovascular tissues [15]. Acetyl-CoA provides acetate groups for histone acetylation, S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) serves as a methyl donor for DNA and histone methylation, and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) functions as substrate for ADP-ribosylation and sirtuin-mediated deacylation [15].

- Novel post-translational modifications: Recently discovered lactylation links glycolytic flux (via lactate) to epigenetic regulation, providing a direct mechanism through which metabolic state influences chromatin architecture and gene expression in cardiovascular cells [15].

- Transcriptional regulation of metabolism: Epigenetic modifications reciprocally regulate metabolic enzyme expression, creating feedback loops that perpetuate metabolic dysfunction in conditions like heart failure, myocardial infarction, and atherosclerosis [15].

Metabolic Dysregulation in Neurodegenerative Disorders

Neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), and Huntington's disease (HD) share common features of metabolic decline that closely track with disease progression [11] [12]. Characteristic features include:

- Cerebral glucose hypometabolism: Position emission tomography (PET) studies consistently reveal reduced glucose utilization in specific brain networks years before overt symptom manifestation [12].

- Mitochondrial dysfunction: Impaired electron transport chain function, increased reactive oxygen species production, and defective quality control mechanisms disrupt cellular energy homeostasis in vulnerable neuronal populations [11].

- Lipid metabolism alterations: Dysregulated phospholipid and sphingolipid metabolism compromises membrane integrity and synaptic function while promoting pathological protein aggregation [11].

- Bile acid metabolism disruptions: Altered circulating and cerebral bile acid profiles contribute to AD and PD pathophysiology through modulation of neurotransmitter signaling and mitochondrial function [11].

Table 1: Key Metabolic Alterations in Neurodegenerative Diseases

| Disease | Primary Metabolic Disturbances | Affected Brain Regions | Imaging Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease | Glucose hypometabolism, Altered bile acid metabolism, Cholesterol dyshomeostasis | Temporoparietal cortex, Posterior cingulate, Prefrontal cortex | FDG-PET hypometabolism, PCC connectivity loss |

| Parkinson's Disease | Glucose hypermetabolism in pallidum, Mitochondrial complex I deficiency, Lipid peroxidation | Basal ganglia, Thalamus, Motor cortex | PDRP network activity, 18F-FDG PET covariance patterns |

| Huntington's Disease | Increased caudate glucose metabolism, Mitochondrial defects, Energy deficit | Caudate/putamen, Cortical regions | CMS hypometabolism, Caudate glucose utilization |

Quantitative Evidence: Causal Relationships and Epidemiological Data

Mendelian Randomization Evidence for Metabolic-Cardiovascular Disease Links

Mendelian randomization studies provide compelling evidence for causal relationships between metabolic disorders and cardiovascular diseases, overcoming limitations of observational studies by minimizing confounding and reverse causation [16]. Genetically predicted metabolic disorders significantly increase risk for multiple cardiovascular conditions:

Table 2: Causal Effects of Metabolic Disorders on Cardiovascular Diseases from Mendelian Randomization Analysis

| Cardiovascular Disease | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Genetic Instruments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary Heart Disease | 1.77 (1.55-2.03) | <0.001 | 14 independent SNPs primarily related to dyslipidemia and obesity |

| Myocardial Infarction | 1.75 (1.52-2.03) | <0.001 | 11 SNPs after outlier removal |

| Heart Failure | 1.26 (1.14-1.39) | <0.001 | 10 SNPs after outlier removal |

| Hypertension | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | 0.002 | 13 SNPs after outlier removal |

| Stroke | 1.19 (1.08-1.32) | <0.001 | 13 SNPs after outlier removal |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 1.03 (0.94-1.12) | Not significant | 14 SNPs |

The concordance of results across multiple complementary sensitivity analyses (MR-Egger, weighted median) reinforces the robustness of these causal inferences [16]. These findings underscore the importance of targeting metabolic disorders to reduce cardiovascular disease development.

Global Burden of MASLD and Transplantation Implications

MASLD represents a substantial and growing global health burden, affecting more than a quarter of adults worldwide [14]. The condition not only creates severe medical burdens for affected individuals but also significantly impacts donor organ availability through several mechanisms:

- Reduced donor pool: MASLD livers demonstrate increased susceptibility to ischemia-reperfusion injury and cold ischemic damage during transplantation procedures [14].

- Post-transplantation complications: Lipid deposition, microcirculation disturbance, and inflammation in MASLD donor livers exacerbate ischemia-reperfusion-related damage, compromising graft function and survival [14].

- Therapeutic implications: Minimizing cold ischemia time, implementing machine perfusion, and applying MASLD-specific treatments after transplantation represent key strategies for preserving graft function in affected organs [14].

Experimental Approaches and Analytical Frameworks

Metabolic Network Modeling Methodologies

Metabolic network analysis provides powerful tools for investigating system-level metabolic alterations across diseases. Multiple complementary approaches enable researchers to model different aspects of metabolic interactions:

Table 3: Metabolic Network Modeling Approaches and Applications

| Network Type | Key Methodologies | Strengths | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation-Based | Pearson/Spearman correlation, Distance correlation, Gaussian graphical models | Identifies coordinated metabolite behaviors, Reveals system-level relationships | Disease pathogenesis studies, Biomarker discovery |

| Causal-Based | Causal inference models, Structural equation modeling (SEM), Dynamic causal modeling (DCM) | Infers directional relationships, Models dynamic system behavior | Mechanistic studies, Intervention prediction |

| Pathway-Based | Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), Flux balance analysis, Constraint-based modeling | Context-specific network reconstruction, Predictive flux simulations | Host-microbiome interactions, Drug target identification |

| Chemical Structure-Based | Chemical similarity networks, Reaction similarity mapping | Links metabolic structure to function, Identifies novel metabolic routes | Enzyme function prediction, Metabolite annotation |

Protocol: Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling for Disease-Specific Metabolic Networks

Purpose: To reconstruct context-specific metabolic networks from multi-omics data for investigating metabolic dysregulation in disease states [11] [13].

Step 1: Network Reconstruction

- Obtain a generic genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., Recon3D for human metabolism, AGORA for microbiome)

- Integrate transcriptomic, proteomic, and/or metabolomic data from disease and control samples

- Implement context-specific extraction algorithms (e.g., FASTCORE, INIT, mCADRE) to generate tissue/cell-type specific models [11]

Step 2: Metabolic Flux Prediction

- Apply constraint-based modeling approaches, including Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and Flux Variability Analysis (FVA)

- Define system constraints based on experimental measurements (uptake/secretion rates, ATP maintenance)

- Optimize for biologically relevant objectives (e.g., biomass production, ATP yield, metabolite production)

Step 3: Network Analysis

- Calculate reaction activity scores across conditions

- Identify differentially active pathways using linear mixed models accounting for patient effects

- Predict metabolic exchanges in microbial communities or host-microbiome systems [13]

Step 4: Validation and Interpretation

- Compare model predictions with experimental metabolomics data

- Perform sensitivity analysis on key reactions

- Integrate network topology metrics (degree centrality, betweenness) to identify critical network nodes

Protocol: Spatial Covariance Analysis of Brain Metabolic Networks

Purpose: To identify disease-specific spatial covariance patterns in functional brain imaging data for neurodegenerative disorders [12].

Step 1: Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Acquire resting-state FDG-PET or fMRI scans from patients and matched controls

- Perform spatial normalization to standard template space

- Apply appropriate smoothing to improve signal-to-noise ratio

Step 2: Scaled Subprofile Model (SSM) Analysis

- Implement SSM/PCA (principal component analysis) on normalized brain images

- Compute group-invariant reference region for scaling

- Extract principal components representing spatially distributed networks

Step 3: Pattern Identification and Validation

- Identify disease-related patterns through discriminant analysis

- Validate patterns in independent test cohorts

- Compute subject scores representing pattern expression in individual patients

Step 4: Longitudinal and Treatment Assessment

- Track pattern expression over time to assess disease progression

- Evaluate network modulation in response to therapeutic interventions

- Correlate network expression with clinical measures of disease severity

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Metabolic Network Studies

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (e.g., Recon3D, AGORA) | Provide biochemical network framework for constraint-based modeling | Context-specific metabolic network reconstruction [11] [13] |

| HRGM (Human Gastrointestinal Microbiome) Collection | Reference genomes for microbiome metabolic modeling | Gut microbiome metabolic network reconstruction in IBD [13] |

| Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) Toolbox | MATLAB-based platform for metabolic flux simulation | Flux balance analysis, metabolic network modeling [11] |

| R/Bioconductor (e.g., ggplot2, limma) | Statistical computing and visualization | Differential expression analysis, data visualization [17] |

| Python Libraries (e.g., NumPy, Pandas, SciPy) | Data manipulation and analysis | Metabolic network construction, statistical analysis [10] [17] |

| Gaussian Graphical Model Packages | Partial correlation analysis for network inference | Correlation-based metabolic network construction [10] |

| Structural Equation Modeling Software (e.g., lavaan) | Causal pathway modeling | Causal metabolic network analysis [10] |

| FDG (Fluorodeoxyglucose) | Tracer for cerebral glucose metabolism | Brain metabolic network mapping in neurodegeneration [12] |

Visualizing Metabolic Networks and Experimental Workflows

Metabolic Network Analysis Workflow

Metabolic Network Analysis Workflow: Integrated computational-experimental pipeline for investigating metabolic networks in disease states.

Host-Microbiome Metabolic Crosstalk in Disease

Host-Microbiome Metabolic Crosstalk: Bidirectional metabolic interactions between host and microbiome in inflammatory diseases like IBD.

Metabolic-Epigenetic Nexus in Cardiovascular Disease

Metabolic-Epigenetic Nexus: Mechanism by which cellular metabolites influence epigenetic modifications to drive cardiovascular disease pathogenesis.

This whitepaper delineates the core principles governing metabolic homeostasis, focusing on the dynamic roles of metabolites, metabolic flux, and energy metabolism. Framed within the context of disease research, we detail how perturbations in metabolic networks—the complex systems of biochemical reactions—contribute to pathological states. The document provides a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals, integrating quantitative data summaries, experimental protocols for flux analysis, and standardized visualizations to facilitate the study of metabolic dysregulation in diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease and cancer.

Core Principles of Metabolic Function and Homeostasis

Metabolism encompasses the sum of all biochemical processes that sustain life, performing four essential functions: (1) energy conversion and ATP production; (2) the breakdown of nutrients (catabolism), which often releases energy; (3) the synthesis of macromolecules (anabolism), which requires energy; and (4) participation in cellular signaling and gene transcription regulation [18]. Homeostasis is maintained through the precise regulation of metabolic flux—the rate at which metabolites flow through biochemical pathways—balancing catabolic and anabolic processes to meet cellular energy and biosynthetic demands.

The direction and rate of metabolic reactions are governed by thermodynamics. The Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) determines whether a reaction releases energy (exergonic, ΔG < 0) or requires energy (endergonic, ΔG > 0) [18]. Enzymes, as biological catalysts, increase the rate of these reactions by lowering the activation energy but do not alter the reaction's ΔG or its directionality [18]. The actual ΔG of a reaction in a cellular context is influenced by the concentrations of reactants and products, as described by the law of mass action [18].

Table 1: Fundamental Functions of Metabolism

| Function | Core Description | Energy Relationship | Key Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Production | Generation of ATP to power cellular functions. | Releases usable energy. | Oxidative Phosphorylation |

| Catabolism | Breakdown of complex nutrients (e.g., fats, proteins) into simpler structures (e.g., fatty acids, amino acids). | Often releases energy. | Glycolysis, β-Oxidation |

| Anabolism | Synthesis of complex macromolecules (e.g., proteins, lipids) from simpler precursors. | Requires energy input. | Cholesterol Synthesis |

| Signaling & Regulation | Metabolites act as substrates for post-translational modifications (e.g., acetylation) or regulate gene expression. | Can require or be regulated by energy. | Protein Acetylation by Acetyl-CoA |

Metabolic Networks and Flux in Systems Biology

A metabolic network is a graphical representation of the interconnected biochemical reactions within a cell or organism. In these networks, metabolites are represented as nodes, and the biochemical reactions that interconvert them are represented as edges [10]. The metabolic connectome refers to the comprehensive map of these physical, biochemical, and functional interactions [10]. Analyzing the properties of these networks—such as node degree, clustering coefficient, and modularity—helps reveal the organization and robustness of the metabolic system and can identify critical control points within pathways [10].

Metabolic flux is the measurable rate of flow of metabolites through a metabolic pathway, representing the functional output of the network [19]. Understanding flux is a threshold concept in biochemistry, as it reveals the dynamic and regulated nature of pathways, showing how carbon and energy journey through the cellular system in response to different conditions, such as hypoxia or in cancer [19]. The concept of metabolic coherence is a quantitative measure used to assess how well gene expression profiles from patient samples align with the structure of a reference metabolic network, thereby inferring the activity state of the network [20].

Constructing and Analyzing Metabolic Networks

Different computational models are employed to construct metabolic networks, each providing unique insights [10]:

- Correlation-Based Networks: Built using statistical correlations (e.g., Pearson, Spearman, Gaussian Graphical Models) between the measured levels of metabolites. While useful for identifying coordinated behaviors, correlation does not imply direct causation [10].

- Causal-Based Networks: Utilize methods like causal inference models, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), and Dynamic Causal Modeling (DCM) to infer directional influences and causal relationships between metabolites from observational data [10].

- Biochemistry-Based Networks: Rely on known biochemical reactions from databases (e.g., Recon2 model) to map the exact pathways of metabolite conversion [20].

Table 2: Methodologies for Metabolic Network Construction

| Network Type | Core Method | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation-Based | Calculates pairwise correlations (e.g., Pearson) between metabolite abundances. | Simplifies complex data; identifies coordinated changes. | Correlations may be indirect; does not imply causation. |

| Causal-Based | Uses algorithms (e.g., SEM, DCM) to infer causal direction from data. | Reveals potential driver relationships and mechanisms. | Model-dependent; requires careful validation. |

| Biochemistry-Based | Curates networks from known metabolic pathways and reaction databases. | Grounded in established biochemical knowledge. | May not reflect condition-specific network states. |

Metabolic Dysregulation in Disease States

Dysregulation of metabolic networks is a hallmark of numerous diseases. Metabolic network coherence analysis has been applied to gene expression data from pediatric inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients, revealing a statistically significant difference in coherence between IBD patients and controls [20]. This approach successfully stratified patients and controls based on distinct metabolic network states, highlighting the crosstalk between metabolism and other vital pathways, such as cellular transport of thiamine and bile acid metabolism [20]. Such network-based stratification provides a powerful approach for reclassifying clinically defined phenotypes and uncovering novel subtypes with potential therapeutic implications.

Furthermore, metabolic flux is notably altered in cancer. The Warburg effect, where cancer cells preferentially utilize glycolysis for energy production even in the presence of oxygen, is a classic example of flux rerouting [19]. Advanced animations and modeling of central carbon metabolism have visualized how fluxes change in cancer, demonstrating how carbon from nutrients like glucose and glutamine is redirected to support rapid cell proliferation and biomass synthesis [19].

Experimental Protocols for Metabolic Analysis

Protocol: Metabolic Network Coherence Analysis

This protocol outlines the process for inferring metabolic network states from gene expression data, as applied in IBD research [20].

- Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: Obtain transcriptomic data (e.g., RNA-Seq) from patient and control tissue samples. Normalize raw read counts using standardized methods (e.g., DESeq2) to generate comparable expression values across samples.

- Define Saliently Expressed Genes: For each individual sample, classify genes as "saliently expressed" if their normalized expression Z-score exceeds a defined threshold (e.g., ±3). This creates a sample-specific set of active genes.

- Map onto a Reference Metabolic Network: Utilize a genome-scale metabolic model, such as Recon2, as a template [20]. Project this model to create a gene-centric metabolic network where genes are nodes, and edges represent functional metabolic connections.

- Construct Sample-Specific Effective Networks: For each sample, map its set of saliently expressed genes onto the gene-centric metabolic network. The resulting subgraph is the "effective metabolic network" for that sample.

- Calculate Metabolic Coherence: Quantify the connectivity and integrity of each sample's effective network. Coherence is a single global quantity per sample, often calculated based on the relative number of connected components and edge density compared to random expectations [20].

- Statistical Analysis and Stratification: Analyze the distribution of coherence values across the cohort. Use mixture model analysis (e.g., Gaussian mixture models) to identify multimodality, which suggests the presence of distinct metabolic states. Correlate these states with clinical phenotypes.

Protocol: Investigating Flux Using Stable Isotope Tracers

This methodology allows for the experimental measurement of metabolic flux in cultured cells or model systems [19].

- Tracer Selection: Choose a stable isotope-labeled nutrient (e.g., U-¹³C-Glucose, ¹³C,¹⁵N-Glutamine) that feeds into the pathway of interest.

- Experimental Incubation: Incubate cells with the tracer-containing medium under defined experimental conditions (e.g., normoxia vs. hypoxia) for a specific duration to allow the tracer to incorporate into metabolic pathways.

- Metabolite Extraction: At designated time points, rapidly quench metabolism (e.g., using cold methanol) and extract intracellular metabolites.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Analyze the metabolite extracts using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS). The mass spectrometer detects the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of metabolites, identifying the incorporation of heavy isotopes.

- Flux Calculation: Use specialized software to model the flow of the labeled atoms through known metabolic network structures. The pattern of isotope enrichment (e.g., M+0, M+1, M+2 masses) for pathway intermediates is used to calculate absolute metabolic fluxes.

Table 3: Key Reagents for Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Tracers (e.g., U-¹³C-Glucose) | Label carbon atoms within nutrients to track their fate through metabolic pathways. |

| LC-MS (Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) | The core analytical platform for separating, detecting, and quantifying labeled metabolites. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (e.g., Recon3D) | Curated computational networks of human metabolism used to contextualize data and simulate fluxes. |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) Software | Constraint-based modeling approach to predict flux distributions in a metabolic network at steady state [20]. |

| Quenching Solution (e.g., Cold Methanol) | Rapidly halts enzymatic activity at the time of harvest to preserve the in vivo metabolic state. |

Quantitative Data in Metabolic Research

The application of quantitative data analysis is fundamental to interpreting complex metabolic data. Techniques range from descriptive statistics, which summarize central tendency and dispersion, to inferential statistics, which test hypotheses about larger populations [21]. Below is a synthesized summary of quantitative findings from metabolic network studies.

Table 4: Quantitative Summary of Metabolic Network Coherence in IBD

| Diagnostic Group | Sample Size (n) | Median Metabolic Coherence | Statistical Significance (p-value) | Identified State (from Mixture Analysis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Individuals | 24 | -0.195 | p = 0.0095 (Kruskal-Wallis test) | State A (Mean: -0.272) |

| Crohn's Disease (CD) Patients | 23 | 0.596 | Not Significant vs. UC (p > 0.2) | State B (Mean: 1.029) |

| Ulcerative Colitis (UC) Patients | 19 | 0.723 | Not Significant vs. CD (p > 0.2) | State B (Mean: 1.029) |

Table 5: Common Quantitative Data Analysis Methods in Metabolism Research

| Analysis Method | Primary Use Case | Key Metric/Output |

|---|---|---|

| Descriptive Statistics | Summarizing metabolite concentration levels across sample groups. | Mean, Median, Standard Deviation, Variance |

| T-Test / ANOVA | Determining if differences in a metabolite's level between two or more groups are statistically significant. | p-value |

| Correlation Analysis | Identifying linear relationships between the levels of different metabolites. | Pearson Correlation Coefficient (r) |

| Regression Analysis | Modeling and predicting the value of a dependent variable (e.g., disease severity) based on metabolic predictors. | R², Regression Coefficients |

| Cross-Tabulation | Analyzing the relationship between categorical variables (e.g., metabolic state vs. clinical response). | Contingency Table, Chi-square statistic |

A deep understanding of metabolites, metabolic flux, and the principles of energy metabolism is indispensable for deciphering system homeostasis. The application of network biology and advanced analytical techniques, such as metabolic coherence analysis and stable isotope tracing, provides a powerful framework for moving beyond static molecular lists to a dynamic, systems-level view. This approach is critical for identifying disease-specific metabolic vulnerabilities, stratifying patient populations based on their underlying metabolic network state, and ultimately informing the development of novel therapeutic strategies aimed at restoring metabolic homeostasis.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains a leading cause of global mortality, with projections indicating a rise to 35.6 million cardiovascular deaths annually by 2050 [22]. The heart, as a high-energy-demand organ, requires continuous ATP production to maintain contractile function and basal metabolism. Myocardial metabolic disorders—alterations in how the heart derives and utilizes energy—are now recognized as fundamental contributors to the pathogenesis and progression of various CVDs, including heart failure, myocardial infarction, and atherosclerosis [23] [24]. This whitepaper explores the core concepts of cardiac energy metabolism, focusing on the shifts between glycolytic and oxidative metabolic pathways in health and disease, and frames these changes within the broader context of metabolic network alterations in disease states.

Energy Metabolism in the Healthy and Diseased Heart

Metabolic Substrate Utilization in the Heart

The healthy adult heart is metabolically flexible, capable of utilizing various substrates to meet its substantial energy demands. Under normal conditions, the heart derives approximately 40-60% of its energy from fatty acid oxidation, with the remainder coming primarily from glucose metabolism, and minor contributions from lactate, ketone bodies, and amino acids [23]. This energy is largely produced via mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, yielding high ATP per molecule of substrate.

Table 1: Primary Energy Sources for Cardiac Myocytes

| Metabolic Substrate | Contribution in Healthy Adult Heart | ATP Yield | Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty Acids (Palmitate) | 40-60% of total ATP [23] | ~106 ATP/molecule | β-oxidation → TCA cycle → OXPHOS |

| Glucose | 10-30% of total ATP [23] | ~30-32 ATP/molecule (if fully oxidized) | Glycolysis → TCA cycle → OXPHOS |

| Lactate | 10-20% of total ATP | ~15 ATP/molecule (per pyruvate equivalent) | Conversion to pyruvate → TCA cycle → OXPHOS |

| Ketone Bodies | 5-10% of total ATP | Varies by type (e.g., ~20 ATP/β-hydroxybutyrate) | Mitochondrial oxidation → TCA cycle → OXPHOS |

Developmental Metabolic Shifts and Loss of Regenerative Capacity

The mammalian heart undergoes a critical metabolic transition shortly after birth that coincides with the loss of regenerative capacity. During embryonic development, cardiomyocytes primarily rely on anaerobic glycolysis, which occurs in a relatively hypoxic environment [23]. This glycolytic metabolism supports cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart regeneration following injury.

Around the first week of postnatal life in mammals, a dramatic metabolic shift occurs: the heart transitions from glycolysis to mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, with fatty acid β-oxidation becoming the dominant energy source [23]. This shift corresponds precisely with the loss of the heart's regenerative capacity. Research demonstrates that 1-day-old neonatal mice can fully regenerate after cardiac injury, while 7-day-old mice lose this ability and develop irreversible fibrosis following injury [23]. This suggests that the metabolic shift from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation may contribute to cell cycle arrest in cardiomyocytes.

Figure 1: Metabolic Shift from Embryonic to Adult Heart and Impact on Regenerative Capacity

Glycolytic Pathways in Cardiovascular Disease

Glycolytic Reprogramming in Heart Failure

In various forms of cardiovascular disease, the heart undergoes metabolic reprogramming characterized by a shift back toward fetal metabolic patterns, with increased reliance on glycolysis despite adequate oxygen availability—a phenomenon analogous to the "Warburg effect" observed in cancer cells [24]. This metabolic shift represents an early adaptive response to cardiac stress but may become maladaptive over time.

In heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), studies in Dahl salt-sensitive rat models have demonstrated that increased glycolysis is the earliest detectable metabolic change, occurring before significant alterations in fatty acid oxidation or overall ATP production rates [25]. This elevated glycolysis often becomes uncoupled from subsequent glucose oxidation, leading to proton accumulation and impaired contractile function.

Table 2: Key Glycolytic Enzymes in Cardiovascular Pathology

| Enzyme | Isoform | Role in Glycolysis | Association with CVD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hexokinase | HK1, HK2 | Catalyzes glucose to glucose-6-phosphate; first committed step | HK2 dissociates from mitochondria during I/R, promoting mPTP opening and apoptosis [26] |

| Phosphofructokinase-1 | PFK1 | Rate-limiting enzyme; converts F6P to F1,6BP | Activity and glycolytic flux increase in HF [26] |

| Pyruvate Kinase | PKM2 | Final step; produces pyruvate and ATP | M2 isoform associated with proliferative and hypertrophic states [26] |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase | LDH | Converts pyruvate to lactate | Elevated in ischemia; serum levels indicate hypoxic burden [26] |

Uncoupling of Glycolysis from Glucose Oxidation

A critical metabolic disturbance in failing hearts is the uncoupling of glycolysis from glucose oxidation. Under normal conditions, glycolytically-derived pyruvate enters mitochondria and is oxidized through the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. In heart failure, while glycolysis increases, glucose oxidation may not proportionately increase, or may even decrease [25].

This uncoupling has significant pathophysiological consequences. For every glucose molecule that undergoes glycolysis but not subsequent oxidation, there is net production of 2 protons, contributing to intracellular acidosis [25]. This acidotic environment impairs calcium handling and myofilament sensitivity, directly reducing contractile efficiency. Additionally, the ATP consumed to restore ionic homeostasis further decreases cardiac efficiency, creating a vicious cycle of worsening function.

Figure 2: Metabolic Consequences of Uncoupled Glycolysis and Glucose Oxidation in Heart Failure

Fatty Acid Metabolism in Cardiovascular Disease

Aberrant Fatty Acid Metabolism

As the primary energy source for the adult heart, fatty acids play a crucial role in myocardial metabolism, and their dysregulation significantly contributes to CVD pathogenesis. Alterations in fatty acid metabolism can lead to myocardial energy imbalance through multiple mechanisms, including lipotoxicity, oxidative stress, inflammation, and mitochondrial dysfunction [27] [28].

Different classes of fatty acids exert distinct effects on cardiovascular health. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), produced by gut microbiota fermentation of dietary fiber, generally exhibit cardioprotective effects through anti-inflammatory mechanisms and improvement of endothelial function via GPR41/43 receptor activation [27] [28]. In contrast, saturated fatty acids (SFAs) promote CVD by inducing lipotoxicity, oxidative stress, and vascular remodeling. The balance between ω-3 and ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) is also critical, with ω-3 PUFAs exerting anti-inflammatory and cardioprotective effects, while excessive ω-6 PUFAs may promote inflammation and disease progression [27] [28].

Table 3: Fatty Acid Classes and Their Roles in Cardiovascular Disease

| Fatty Acid Class | Major Types | Primary Effects in CVD | Proposed Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Chain Fatty Acids | Acetate, Propionate, Butyrate | Cardioprotective [27] | Anti-inflammatory; improve endothelial function via GPR41/43 activation; reduce oxidative stress |

| Medium-Chain Fatty Acids | C8:0, C10:0, C12:0 | Neutral/Mixed effects | Direct mitochondrial import; rapid β-oxidation; may reduce lipotoxicity |

| Long-Chain Saturated FA | Palmitate (C16:0), Stearate (C18:0) | Promote CVD [27] | Induce lipotoxicity, oxidative stress, inflammation, and vascular remodeling |

| ω-3 Polyunsaturated FA | EPA (20:5), DHA (22:6) | Cardioprotective [27] | Anti-inflammatory; modulate lipid metabolism; inhibit platelet aggregation |

| ω-6 Polyunsaturated FA | Arachidonic Acid (20:4) | Generally promote CVD [27] | Pro-inflammatory eicosanoid production; promote disease progression |

Key Regulatory Nodes in Fatty Acid Metabolism

Several molecular regulators serve as critical control points in fatty acid metabolism and represent potential therapeutic targets:

CD36: A fatty acid transporter protein that facilitates cellular uptake of long-chain fatty acids. CD36 dysfunction is associated with impaired fatty acid utilization and lipotoxicity in cardiomyocytes [27] [28].

CPT1 (Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase 1): The rate-limiting enzyme in mitochondrial fatty acid uptake. CPT1 activity determines the flux of fatty acids into β-oxidation and is regulated by malonyl-CoA levels [27] [28].

PPARs (Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors): Nuclear transcription factors that regulate expression of genes involved in fatty acid uptake, metabolism, and storage. PPARα activation enhances fatty acid oxidation capacity [27] [28].

AMPK (AMP-activated Protein Kinase): An energy-sensing kinase that activates fatty acid oxidation during energy stress while inhibiting anabolic processes. AMPK activation improves metabolic flexibility and cardiac efficiency [27] [28].

Metabolic Networks in Cardiovascular Disease Research

Metabolic Connectome and Network Analysis

The study of myocardial metabolic disorders has evolved from examining individual pathways to investigating complex metabolic networks. The "metabolic connectome" represents the comprehensive network of metabolic interactions within a biological system, where metabolites serve as nodes and their biochemical interactions as edges [10]. This network approach provides a systems-level understanding of metabolic regulation and dysfunction in CVD.

Metabolic networks can be constructed using various relationship types, including:

- Correlation-based networks: Utilize statistical correlations between metabolite levels to infer connectivity

- Causal-based networks: Employ causal inference models to establish directional relationships between metabolites

- Pathway-based networks: Built upon established biochemical pathways and reaction networks

- Chemical structure similarity-based networks: Group metabolites by structural similarities [10]

Network analysis metrics such as node degree, clustering coefficient, average shortest path length, and centrality help identify critical control points in metabolic networks that may represent promising therapeutic targets for CVD intervention [10].

Applications of Metabolic Network Analysis in CVD

Metabolic network analysis has emerged as a powerful tool for elucidating disease mechanisms, predicting and diagnosing diseases, and facilitating drug development [10]. By mapping gene expression profiles onto metabolic networks, researchers can identify distinct metabolic states in cardiovascular tissues that correlate with disease progression and treatment response.

This approach has revealed that patterns of metabolic network "coherence"—how well individual patterns of expression changes match the underlying metabolic network structure—can distinguish between diseased and healthy states, and may identify subtypes within cardiovascular disease populations with different metabolic characteristics and potential treatment responses [20].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Isolated Working Heart Perfusion for Metabolic Flux Analysis

The isolated working heart preparation provides a robust experimental system for directly assessing cardiac energy metabolism. This methodology allows precise control of perfusion conditions and simultaneous measurement of mechanical function and metabolic fluxes [25].

Protocol:

- Heart Excisions: Hearts are rapidly excised from anesthetized rats and immediately placed in ice-cold buffer.

- Aortic Cannulation: The aorta is cannulated for initial Langendorff (retrograde) perfusion with oxygenated Krebs-Henseleit buffer.

- Working Heart Mode Conversion: The perfusion is switched to working mode by introducing left atrial perfusion at 11.5 mmHg preload against an 80 mmHg aortic afterload.

- Substrate Supplementation: The perfusion buffer is supplemented with physiological concentrations of energy substrates:

- 5 mM glucose

- 0.5 mM lactate

- 0.8 mM palmitate bound to 3% fatty acid-free BSA

- Isotope Tracers for Flux Measurements:

- [U-14C] glucose to measure glucose oxidation (via 14CO2 collection)

- [5-3H] glucose to measure glycolytic flux (via 3H2O production)

- [9,10-3H] palmitate to measure fatty acid oxidation (via 3H2O production)

- Functional Assessment: Cardiac function parameters (aortic pressure, cardiac output, heart rate) are continuously monitored throughout the perfusion.

- Metabolite Analysis: Perfusate and tissue samples are collected for subsequent biochemical analysis [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Cardiac Metabolism Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isotopic Tracers | [U-14C] glucose, [5-3H] glucose, [9,10-3H] palmitate | Metabolic flux analysis [25] | Tracing specific metabolic pathways; quantifying substrate oxidation rates |

| Fatty Acid Probes | BODIPY-labeled fatty acids, [125I]-BMIPP | Fatty acid uptake imaging | Visualizing and quantifying cellular fatty acid uptake and trafficking |

| Metabolic Inhibitors/Activators | Etomoxir (CPT1 inhibitor), Dichloroacetate (PDK inhibitor) | Pathway modulation [25] | Targeting specific metabolic enzymes to investigate pathway functions |

| Antibodies for Metabolic Proteins | Anti-CD36, Anti-GLUT4, Anti-HK2, Anti-PPARα | Protein expression analysis | Detecting protein abundance, localization, and post-translational modifications |

| Metabolomics Kits | Targeted LC-MS kits for acyl-carnitines, TCA intermediates, glycolytic intermediates | Metabolic profiling | Comprehensive assessment of metabolite levels in tissues and biofluids |

Myocardial metabolic disorders represent a fundamental aspect of cardiovascular disease pathophysiology, characterized by shifts in energy substrate utilization, impaired metabolic flexibility, and disrupted network-level metabolic regulation. The transition from fatty acid oxidation to glycolytic metabolism in the failing heart, while initially adaptive, ultimately contributes to contractile dysfunction and disease progression through mechanisms such as uncoupled glucose metabolism and proton-mediated toxicity.

Understanding these metabolic alterations within the framework of metabolic networks provides valuable insights for developing targeted therapeutic interventions. Strategies that restore metabolic balance—such as improving the coupling of glycolysis to glucose oxidation, modulating fatty acid utilization, or targeting key regulatory nodes in metabolic networks—hold significant promise for the future of cardiovascular medicine. As metabolic network analysis technologies continue to advance, they will undoubtedly uncover novel diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets, ultimately enabling more personalized approaches to CVD management based on individual metabolic phenotypes.

The brain's immense energy demand makes it uniquely vulnerable to age-related metabolic decline. While representing only 2% of body weight, the brain consumes 20% of the body's glucose and 70-80% of its ATP, with neurons being particularly energy-dependent cells [29]. Emerging research positions metabolic dysregulation as a fundamental driver of brain aging, creating a state of metabolic fragility characterized by reduced robustness, flexibility, and adaptability of the brain's energy systems [30]. This metabolic network disruption initiates a cascade of events: impaired cellular metabolism leads to dysfunctional cell-cell interactions, ultimately promoting a malignant microenvironment conducive to neurodegenerative diseases [31]. Understanding these multilayered metabolic networks provides critical insights for developing interventions against age-related cognitive decline. This whitepaper examines the mechanisms underlying the aging brain's metabolic fragility and its consequences for cognitive function, framing these changes within the broader context of metabolic network alterations in disease states.

Core Mechanisms of Metabolic Fragility in the Aging Brain

Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Energy Crisis

The aging brain experiences a progressive failure in mitochondrial energy production, which constitutes a central aspect of metabolic fragility. Mitochondria in aged neurons exhibit impaired oxidative phosphorylation and reduced ATP synthesis, directly impacting neuronal excitability and synaptic function [29]. The tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle shows significant alterations with aging, including abnormal accumulations of citrate and succinate, and reduced catalytic activity of pyruvate dehydrogenase, leading to decreased acetyl-CoA production [29]. These changes create an energy deficit that particularly affects metabolically demanding processes such as action potential generation and neurotransmitter recycling.

Table 1: Key Metabolic Alterations in the Aging Brain

| Metabolic Parameter | Young Brain Profile | Aged Brain Profile | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATP Production | Optimal levels maintained | Significantly reduced | Impaired neuronal firing |

| Na+/K+-ATPase Activity | High activity | Markedly reduced | Disrupted ion homeostasis |

| Glycolytic Flux | Balanced with PPP | Often excessive | Reduced antioxidant capacity |

| Mitochondrial TCA Cycle | Normal flux | Reduced flux & citrate accumulation | Impaired energy generation |

| Lactate Levels | Balanced | Elevated in aging | Potential signaling disruption |

| NAD+ Pool | Adequate levels | Reduced | Impaired sirtuin activity & signaling |

Metabolic Network Destabilization

The aging process fundamentally reorganizes metabolic networks, reducing their resilience. A comprehensive molecular model of the neuro-glia-vascular system revealed that metabolic pathways cluster more closely in the aged brain, suggesting a loss of robustness and adaptability [30]. This increased metabolic rigidity undermines the system's capacity to efficiently respond to stimuli and recover from damage. The model, comprising 16,800 biochemical interaction pathways, identified reduced metabolic flexibility as a key characteristic of the aged brain, making it more vulnerable to molecular damage and other challenges affecting enzyme and transporter functions [30] [32]. The interdependencies of molecular reactions create a system where disruption in one pathway can have cascading effects throughout the metabolic network.

Neuro-Glia Metabolic Uncoupling

The coordinated energy metabolism between neurons and astrocytes becomes compromised in the aging brain. The astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle, which provides metabolic support during neuronal activation, shows age-related dysfunction [29]. Contrary to previous assumptions about "selfish glia," research indicates that astrocytes may subserve the metabolic stability of neurons during aging, though this supportive function becomes impaired [30]. The metabolic model predictions suggest that reduced Na+/K+-ATPase activity constitutes the leading cause of impaired neuronal action potentials in aging, directly linking metabolic support to electrical activity [30]. This metabolic uncoupling extends to the neuro-vascular unit, where blood flow regulation and nutrient delivery become less responsive to neuronal demands.

Quantitative Assessment of Brain Aging

The Brain Age Gap as a Metabolic Biomarker

The Brain Age Gap (BAG) has emerged as a powerful neuroimaging-derived biomarker that quantifies deviation from normal brain aging. Computed using machine learning models trained on neuroimaging data from healthy individuals, BAG represents the difference between an individual's estimated brain age and their chronological age [33]. A positive BAG indicates accelerated brain aging, with each one-year increase in BAG raising Alzheimer's risk by 16.5%, mild cognitive impairment by 4.0%, and all-cause mortality by 12% [34]. The highest-risk quartile (Q4) shows a 2.8-fold increased risk of Alzheimer's disease and a 6.4-fold risk of multiple sclerosis [34]. Cognitive decline is most evident in this group, particularly affecting reaction time and processing speed.

Table 2: Brain Age Gap (BAG) Risk Associations Across Modalities

| Imaging Modality | Primary Aging Features Measured | Clinical Associations | Model Performance (MAE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural MRI | Gray matter volume, cortical thickness | Alzheimer's disease, general cognitive decline | 2.68-3.20 years |

| Molecular PET | Metabolic activity, neurotransmitter systems | Early neurodegenerative changes | Research ongoing |

| Functional MRI | Functional connectivity, network organization | Neuropsychiatric disorders, cognitive reserve | Research ongoing |

| Diffusion MRI | White matter integrity, microstructural changes | Processing speed, executive function | Research ongoing |

Metabolic Signatures of Cognitive Decline

Specific metabolic patterns emerge in the aging brain that correlate with cognitive impairment. Research indicates that reducing blood glucose while increasing blood ketone and lactate levels could help restore metabolic function in aging brains [32]. The nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) pool declines with age, impairing vital signaling pathways and energy metabolism [30] [29]. Additionally, methylglyoxal (MG), a highly reactive byproduct of glycolysis, accumulates in aging and can induce cellular dysfunction through chemical modification of proteins and lipids [29]. These metabolic signatures provide potential targets for intervention and biomarkers for tracking cognitive decline.

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Computational Modeling of Brain Metabolism

The development of comprehensive, data-driven molecular models represents a breakthrough in simulating the complex relationships between the aging brain, energy metabolism, blood flow, and neuronal activity.

Experimental Protocol: Neuro-Glia-Vascular System Modeling

- Model Construction: The most comprehensive molecular model to date integrates the neuro-glia-vascular system, comprising 16,800 interaction pathways including all key enzymes, transporters, metabolites, and circulatory factors vital for neuronal electrical activity [30].

- Aging Simulation: RNA expression fold changes from mouse cell-type studies are used to scale enzyme and transporter concentrations, simulating aging by incorporating changes in arterial glucose, lactate, β-hydroxybutyrate levels, total NAD+ pool, and synaptic glutamate concentration changes [30].

- Model Validation: The model is extensively validated against experimental data not used in its construction, confirming its accuracy in predicting changes in biochemical activity in neurons with age [30] [32].

- Intervention Screening: The model performs unguided optimization searches to identify potential interventions capable of restoring the brain's metabolic flexibility and action potential generation [30].

In Vivo and In Vitro Assessment Methods

Multiple experimental approaches are employed to validate metabolic changes and test potential interventions in model systems.

Experimental Protocol: Theta-Shaking Intervention in Senescence-Accelerated Mice

- Intervention: Senescence-accelerated mouse prone-10 (SAMP10) mice are exposed to low-frequency (5 Hz) "theta-shaking" whole-body vibration for 30 weeks [35].

- Behavioral Assessment: Spatial memory is evaluated using Y-maze spontaneous alternation test at 10, 20, and 30 weeks. Anxiety-related behavior is assessed using marble burying test [35].

- Tissue Analysis: Histological and immunohistochemical analyses are conducted to assess neuronal density and protein expression (PGC1α, BDNF, NT-3) in hippocampal subregions (CA1, subiculum) and lateral septum [35].

- Statistical Analysis: Data are analyzed using appropriate statistical tests (e.g., repeated measures ANOVA for behavioral data) with significance set at p < 0.05 [35].

Intervention Strategies and Research Tools

Targeted Metabolic Interventions

Research has identified multiple strategic interventions capable of counteracting metabolic fragility in the aging brain.

Table 3: Metabolic Intervention Strategies for Brain Aging

| Intervention Category | Specific Approach | Proposed Mechanism | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| NAD+ Modulation | NAD-boosting supplements | Enhance sirtuin activity, improve mitochondrial function | Computational prediction [30] [32] |

| Ketogenic Strategies | Increase β-hydroxybutyrate | Provide alternative energy substrate, reduce glycolysis dependence | Model optimization [30] |

| Lactate Supplementation | Increase blood lactate levels | Enhance astrocyte-neuron energy shuttle, signaling functions | Model prediction [30] [29] |

| Glycolytic Regulation | Reduce blood glucose | Limit harmful glycolysis byproducts, improve insulin sensitivity | Lifestyle intervention correlation [29] [32] |

| Transcription Factor Targeting | Activate ESRRA | Enhance mitochondrial biogenesis, oxidative metabolism | Identified as central aging target [30] [32] |

| Non-Invasive Stimulation | Theta-shaking (5 Hz WBV) | Increase PGC1α expression, mitochondrial biogenesis | Mouse model validation [35] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Brain Metabolism in Aging

| Reagent/Resource | Application | Function/Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| iColonEpithelium GEM | Genome-scale metabolic modeling | Computational framework for simulating metabolic networks in colonic epithelium (6,651 reactions, 4,072 metabolites) [1] |

| Neuro-Glia-Vascular Model | Brain metabolism simulation | Open-source model with 16,800 biochemical interactions for simulating young vs. aged brain metabolism [30] |

| Gs-Rb1 (Ginsenoside-Rb1) | Glycolysis modulation | Increases sirtuin 3 activity, benefitting glycolysis and local energy supply in aging models [29] |

| CMS121 and J147 Compounds | Acetyl-CoA regulation | Increase acetyl-CoA levels by inhibiting acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1, preserving mitochondrial homeostasis [29] |

| 3D Vision Transformer | Brain age estimation | Deep learning framework for estimating brain age from T1-weighted MRI scans (MAE: 2.68-3.20 years) [34] |

The aging brain undergoes a systematic metabolic breakdown characterized by mitochondrial dysfunction, network destabilization, and neuro-glia uncoupling. This metabolic fragility directly impairs neuronal function and promotes cognitive decline, creating a vulnerable substrate for neurodegenerative diseases. The emergence of comprehensive computational models and the validation of the Brain Age Gap as a predictive biomarker provide researchers with powerful tools for quantifying these changes and screening potential interventions. Successful strategies appear to share a common theme: enhancing metabolic flexibility by providing alternative energy substrates, reducing harmful metabolic byproducts, and activating transcriptional programs that support mitochondrial health. Future research should focus on validating these computational predictions in human studies, developing targeted delivery systems for metabolic interventions, and exploring combination approaches that address multiple aspects of metabolic network dysfunction simultaneously.

The concept of the metabolic phenotype represents the overall characterization of an individual's metabolites at a specific point in time, precisely reflecting the complex interactions among genetic background, environmental factors, lifestyle, and gut microbiome [36]. This phenotype serves as a key molecular link between healthy homeostasis and disease-related metabolic disruption, functioning as a crucial "bridge" for analyzing the mechanisms of complex diseases [36]. In recent years, high-throughput metabolomics strategies have enabled the systematic analysis of small molecule metabolites in physiological and pathological processes, providing unprecedented insights into how genetic variations propagate through biological systems to manifest as clinical disease phenotypes.

The transition from genotype to phenotype occurs through multilayered regulatory networks that influence metabolic flux, pathway dynamics, and ultimately systemic physiology. Metabolic deficiencies arise when disruptions at the genetic level impair the function of these networks, leading to pathological states in complex diseases such as diabetes and cancer [36]. Unlike traditional single-target approaches that often fail to fully explain disease processes involving multiple metabolic pathways, metabolic phenotypes provide comprehensive physiological fingerprints of an organism's functional state, effectively reflecting physiological and pathological conditions across various levels from small molecules to the whole organism [36].

Genetic Foundations of Metabolic Diseases

Large-Scale Genetic Mapping of Metabolism

Recent advances in genetic mapping have dramatically improved our understanding of the genetic architecture underlying metabolic variation. A landmark 2025 study created the largest genetic map of human metabolism to date, examining the consequences of genetic variation on blood levels of 250 small molecules—including lipids and amino acids—using data from half a million individuals through the UK Biobank [37]. This research systematically identified genes contributing to human metabolism across diverse populations and revealed that genetic control of metabolites remains remarkably consistent across ancestries and between men and women, suggesting that fundamental metabolic regulatory mechanisms are shared across human populations [37].

The study employed sophisticated computational approaches to link genetic variants with metabolite levels, identifying hundreds of genes—including novel ones—that govern blood molecule levels. For example, researchers newly identified the VEGFA gene as potentially controlling aspects of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol metabolism, highlighting potential new avenues for developing medicines to prevent cardiovascular diseases [37]. Such large-scale genetic studies provide the foundational framework for understanding how inherited genetic variation contributes to metabolic deficiencies that predispose to complex diseases.

Table 1: Key Genetic Findings from Large-Scale Metabolic Mapping Studies

| Genetic Factor | Metabolic Influence | Disease Association | Research Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| VEGFA | HDL cholesterol metabolism | Cardiovascular disease | Novel therapeutic target for lipid management |

| APOE polymorphisms | Lipid metabolism regulation | Alzheimer's disease, cardiovascular disease | Well-established modulator of lipid metabolism |

| CYP450 polymorphisms | Drug metabolism efficiency | Variable drug toxicity and efficacy | Critical for pharmacogenomics and personalized medicine |

| Brain insulin receptor network | Glucose metabolism, eating behavior | Obesity, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome | Links early life stress to adult metabolic disease risk |

Expression-Based Polygenic Scores and Metabolic Susceptibility

Beyond individual genetic variants, expression-based polygenic scores (ePRS) represent an innovative approach to consolidating the effects of thousands of genetic variants that exert small cumulative effects over the lifetime. These scores reflect individual variation in the expression of tissue-specific gene co-expression networks and have proven particularly valuable for understanding metabolic disease susceptibility [38]. For instance, brain-based insulin receptor ePRS (ePRS-IR) can identify risk for metabolic and frailty outcomes in older adults, with the mesocorticolimbic ePRS-IR moderating the association between early adversity and increased visceral adipose tissue as well as metabolic syndrome in adult women [38].

Research has demonstrated that the mesocorticolimbic ePRS-IR moderates the association between early life stress and increased visceral adipose tissue as well as metabolic syndrome, with consistently stronger effects observed in women versus men [38]. This suggests that variations in the function of the brain insulin receptor network influence susceptibility to the long-term metabolic effects of adversity, highlighting a target system for prevention and novel treatments. The characterization of the prefrontal and striatal expression-based polygenic score for the insulin receptor gene network (ePRS-IR-PFC-STR) revealed 37 hub-bottleneck genes within the 258-gene co-expression network, with the CTCF gene emerging as the most representative hub-bottleneck gene with previously established roles in insulin biology [38].

Metabolic Dysregulation in Diabetes

Insulin Signaling and Metabolic Phenotypes

Insulin regulates peripheral glucose metabolism and acts as a neuromodulator in the brain, playing a key role in linking early life adversity to the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders, increased body fat, and metabolic disturbances [38]. In brain regions such as the prefrontal cortex, ventral striatum/nucleus accumbens, ventral tegmental area, hippocampus, hypothalamus, and amygdala, insulin influences memory, attention, reward sensitivity, inhibitory control, energy balance, and eating behavior [38]. These regions are strongly affected by early adversity, suggesting a potential link between early life stress and insulin signaling disruption that contributes to long-term metabolic disturbances.

The metabolic phenotype in diabetes is characterized by several hallmark features, including impaired mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and disrupted circadian metabolic rhythms [36]. For instance, insulin sensitivity normally peaks in the morning and declines throughout the day, while hepatic gluconeogenesis increases at night to maintain glucose homeostasis during fasting. Disruptions to this temporal organization, such as nighttime eating, can inhibit fat oxidation, promote lipid storage, and increase obesity risk [36]. Additionally, uncontrolled hepatic gluconeogenesis can lead to fasting hyperglycemia—a fundamental defect in type 2 diabetes.

Diagram 1: Brain Insulin Signaling in Metabolic Disease Pathogenesis. This pathway illustrates how early adversity interacts with brain insulin receptor networks to drive progression toward type 2 diabetes.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Metabolic Inflexibility

Mitochondrial dysfunction represents a core feature of diabetic metabolism, particularly in skeletal muscle and liver tissue. In the context of cancer cachexia, research has identified impaired cAMP-PKA-CREB1 signaling as a driver of mitochondrial dysfunction in skeletal muscle, contributing to persistent muscle wasting despite adequate nutrition [39]. Similarly, studies of hepatocyte function have demonstrated that mitochondrial NAD+ content—regulated by the mitochondrial NAD+ transporter SLC25A51—serves as a key determinant of liver regeneration capacity [39]. These findings highlight the fundamental role of mitochondrial metabolism in maintaining tissue homeostasis and the pathological consequences when these systems become dysregulated.