Emerging Biomarkers for Metabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes: From Pathophysiology to Precision Medicine

This comprehensive review synthesizes the latest advancements in biomarker science for Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM), targeting researchers and drug development professionals.

Emerging Biomarkers for Metabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes: From Pathophysiology to Precision Medicine

Abstract

This comprehensive review synthesizes the latest advancements in biomarker science for Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM), targeting researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational pathophysiology linking these conditions, including chronic inflammation, insulin resistance, and multi-organ crosstalk. The article details established and novel biomarkers—from traditional inflammatory markers and HOMA-IR to emerging candidates like suPAR, Galectin-3, and specific metabolite panels. It critically evaluates methodological approaches in biomarker discovery, including metabolomics and multi-omics integration, while addressing key challenges in clinical validation, specificity, and standardization. Finally, we discuss the translation of these biomarkers into improved risk stratification, therapeutic monitoring, and personalized treatment strategies, framing their potential to reshape early intervention and drug development.

Unraveling the Pathophysiological Web of MetS and T2DM

The conceptual understanding of metabolic disorders has undergone a profound transformation over recent decades, evolving from a collection of distinct risk factors into sophisticated models of multisystemic dysfunction. This progression from Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) to the comprehensive Cardiovascular-Renal-Hepatic-Metabolic (CRHM) syndrome framework reflects an increasingly nuanced appreciation of the interconnected pathophysiological processes that drive disease progression across organ systems. For researchers and drug development professionals, this evolution carries significant implications for biomarker discovery, therapeutic targeting, and clinical trial design. The integration of omics technologies, advanced analytics, and population-specific considerations is reshaping our approach to these complex conditions, particularly within the context of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes research. This whitepaper traces the conceptual evolution of syndrome terminology, examines the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms, and explores the biomarker and therapeutic innovations that are enabling more precise, effective interventions for these interconnected conditions.

The Historical Trajectory of Syndrome Concepts

The conceptual framework for understanding metabolic disorders has progressed through several distinct phases, each building upon previous understanding while incorporating new clinical and scientific insights.

Metabolic Syndrome: The Foundational Concept

The concept of metabolic clustering was first formally recognized in 1988 when Gerald Reaven introduced "Syndrome X," highlighting insulin resistance as a central pathological feature connecting hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia [1]. This cluster was subsequently operationalized in 2001 by the National Cholesterol Education Program—Third Adult Treatment Panel (NCEP-ATP III), which established diagnostic criteria requiring at least three of five components: abdominal obesity, elevated triglycerides, reduced HDL cholesterol, elevated blood pressure, and elevated fasting glucose [1]. While clinically useful for identifying at-risk individuals, this binary diagnostic approach failed to capture disease severity or the full spectrum of cardiometabolic risk [1].

Intermediate Conceptual Developments

Between 2004-2008, the Cardio-Renal Syndrome (CRS) framework emerged, categorizing five subtypes based on primary organ dysfunction and disease chronicity [2]. This recognized the bidirectional relationship between heart and kidney disorders but remained limited in scope. In 2012, the "Circulatory Syndrome" concept proposed refining MetS by incorporating markers of cardiovascular disease including renal impairment, microalbuminuria, arterial stiffness, and ventricular dysfunction [3]. This represented an important step toward a more integrated view of metabolic-cardiovascular interactions.

Contemporary Syndrome Frameworks

Table 1: Evolution of Syndrome Concepts in Metabolic Disease

| Year | Concept | Key Components | Advancements | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1988 | Syndrome X [1] | Insulin resistance, hypertension, dyslipidemia | Identified insulin resistance as central defect | Limited component scope |

| 2001 | Metabolic Syndrome (NCEP-ATP III) [1] | 3 of 5 criteria: waist circumference, triglycerides, HDL-C, blood pressure, fasting glucose | Standardized clinical diagnosis | Binary diagnosis; no severity grading |

| 2004-2008 | Cardio-Renal Syndrome (CRS) [2] | 5 subtypes based on primary organ and acuity | Recognized heart-kidney interactions | Excluded liver and broader metabolic aspects |

| 2012 | Circulatory Syndrome [3] | Added renal impairment, microalbuminuria, arterial stiffness to MetS | Incorporated vascular and renal damage markers | Limited adoption in guidelines |

| 2023 | Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic (CKM) Syndrome [4] | Metabolic risk factors, CKD, cardiovascular system | AHA-recognized; staging system | Underemphasized liver involvement |

| 2024-2025 | Cardiovascular-Renal-Hepatic-Metabolic (CRHM) Syndrome [4] [2] | CVD, CKD, MASLD, obesity, T2DM, dyslipidemia, hypertension | Includes hepatic system; comprehensive multiorgan view | Complex staging; emerging validation needs |

In 2023, the American Heart Association introduced Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic (CKM) syndrome, defining it as "a systemic disorder characterized by pathophysiological interactions among metabolic risk factors, CKD, and the cardiovascular system leading to multiorgan dysfunction and a high rate of adverse cardiovascular outcomes" [4] [1]. This framework incorporated a staging system from stage 0 (no risk factors) to stage 4 (clinical CVD with complications) to capture disease progression [4].

Most recently in 2025, Theodorakis and Nikolaou proposed expanding CKM to CRHM syndrome to incorporate the liver's pivotal role, defining it as "a systemic disorder that leads to parallel multiorgan dysfunction driven by shared pathophysiological mechanisms, including metabolic inflammation (meta-inflammation) and dysregulation, especially insulin resistance" [4] [2]. This expansion acknowledges metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) as both a driver and consequence of systemic metabolic dysfunction, completing the conceptual integration of major organ systems [4].

Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Continuum

The progression from isolated metabolic abnormalities to multisystemic dysfunction follows a recognizable pathophysiological continuum driven by core mechanistic processes.

Central Role of Adipose Tissue Dysfunction

Obesity, particularly visceral adiposity, initiates the pathological cascade through adipose tissue dysfunction characterized by impaired adipogenesis, resistance to insulin-mediated suppression of lipolysis, reduced fatty acid uptake, and excessive collagen deposition [1]. These structural and functional abnormalities promote chronic low-grade inflammation through immune cell infiltration and proinflammatory cytokine release [1]. When subcutaneous adipose storage capacity is exceeded, lipids accumulate in visceral depots and ectopic sites including liver, skeletal muscle, pancreas, and renal sinus [1].

Lipotoxicity and Organ-Specific Damage

Ectopic fat accumulation produces lipotoxicity—a toxic overload of lipids in non-adipose tissues that triggers organ-specific fibro-inflammatory responses [1]. The severity of cellular injury depends on factors including tissue resilience and the balance between inflammatory and fibrotic signaling [1]. This process contributes to insulin resistance, atherosclerosis, cardiac remodeling, hepatic inflammation (MASLD/MASH), and renal impairment [1].

Core Pathophysiological Drivers

Four interconnected pathophysiological drivers create a self-perpetuating cycle of multi-organ dysfunction in CRHM syndrome:

- Chronic Inflammation: Foundation of tissue damage through pro-inflammatory cytokines, immune activation, and fibrotic changes [2]

- Insulin Resistance: Fuels metabolic dysfunction, hyperglycemia, and lipid dysregulation [2]

- Oxidative Stress: Amplifies cellular injury through mitochondrial dysfunction and reactive oxygen species production [2]

- Endothelial Dysfunction: Impairs vascular integrity, increases arterial stiffness, and perpetuates ischemic injury [2]

These shared mechanisms explain the clinical clustering of conditions within CRHM syndrome and provide targets for therapeutic intervention.

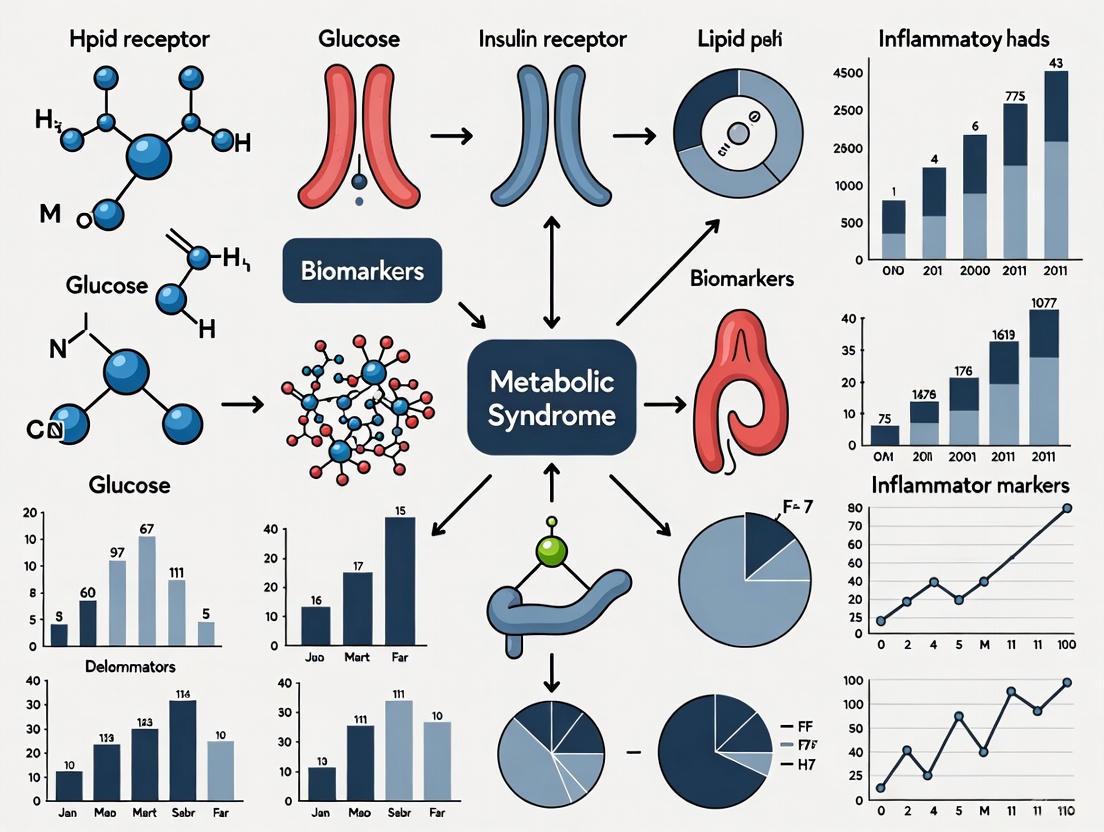

Diagram Title: Pathophysiological Pathways in CRHM Syndrome

Biomarker Advancements in Syndrome Research

The evolving syndrome concepts have driven corresponding advancements in biomarker research, particularly for metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes, with emerging biomarkers offering improved diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic monitoring capabilities.

Traditional and Emerging Circulating Biomarkers

Table 2: Biomarkers in Metabolic Syndrome and CRHM Syndrome Research

| Category | Biomarker | Association/Function | Research Utility | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Biomarkers | HbA1c [5] | Long-term glycemic control | Diabetes diagnosis and monitoring | Limited in certain populations |

| HOMA-IR [5] | Insulin resistance assessment | Research on insulin sensitivity | Lack of standardization | |

| CRP [2] | Systemic inflammation | Cardiovascular risk assessment | Limited specificity | |

| Emerging Circulating Biomarkers | suPAR [2] | Systemic chronic inflammation | Renal disease progression, cardiovascular risk | Stable inflammatory marker |

| GDF-15 [5] [2] | Cellular stress response, mitochondrial dysfunction | Obesity, insulin resistance, cardiovascular aging | Higher in males, older adults | |

| Galectin-3 [2] | Fibrosis and inflammation regulation | Cardiac remodeling, hepatic fibrosis, kidney disease | Multi-organ fibrosis marker | |

| Novel Omics-Based Biomarkers | miRNA-126 [2] | Vascular integrity | Endothelial dysfunction, atherosclerosis | Potential therapeutic target |

| miRNA-423-5p [2] | Heart failure progression | HF diagnosis and monitoring | Requires validation | |

| DNA methylation patterns [6] | Gene expression regulation | T2D risk prediction, early detection | Tissue-specific patterns | |

| Organ-Specific Biomarkers | ALDH3A1, CDK1, DEPDC1, HKDC1, SOX9 [5] | Glycolysis-related genes in MAFLD | MAFLD progression, immune infiltration | Hepatocyte-fibroblast-macrophage axis |

Growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF-15), a member of the TGF-β superfamily upregulated under cellular stress, has emerged as a promising biomarker with demonstrated associations with obesity, insulin resistance, and demographic factors. In a study of 2,083 participants from the Kuwait Diabetes Epidemiology Program, GDF-15 levels were significantly higher in males (580.6 vs. 519.3 ng/L, p < 0.001), participants >50 years (781.4 vs. 563.4 ng/L, p < 0.001), and those of Arab ethnicity compared to South/Southeast Asians [5]. Positive correlations were observed with BMI, waist circumference, blood pressure, insulin, and triglycerides, supporting its role as a metabolic disorder biomarker [5].

Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) has emerged as a stable inflammatory biomarker associated with renal disease progression, cardiovascular risk, and metabolic disorders. Elevated suPAR levels correlate with CKD, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery calcification, with genetic studies linking suPAR to proinflammatory monocyte activation and vascular dysfunction [2].

Epigenetic Biomarkers and Omics Technologies

Epigenetic modifications, particularly DNA methylation, represent promising biomarker sources for T2D risk prediction and understanding disease mechanisms. DNA methylation (5-methylcytosine) at CpG sites regulates gene expression and is influenced by environmental factors including diet, chemical exposures, and chronic stress [6]. Microarray-based studies have identified epigenetic associations with T2D in blood and pancreatic β-cells, though sequencing-based approaches are increasingly advocated for improved genome-wide coverage [6].

The integration of multi-omics approaches is advancing biomarker discovery for complex metabolic conditions. In MAFLD research, integrative analysis of bulk RNA-seq, single-cell RNA-seq, and spatial transcriptomics has identified glycolysis-related key genes (ALDH3A1, CDK1, DEPDC1, HKDC1, SOX9) that discriminate MAFLD progression and interact with immune infiltration processes [5]. Single-cell analysis revealed the hepatocyte-fibroblast-macrophage axis as the predominant glycolysis-active niche, while spatial transcriptomics showed colocalization of CDK1, SOX9, and HKDC1 with the monocyte-derived macrophage marker CCR2 [5].

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Research into CRHM syndrome and its components employs diverse experimental approaches spanning basic science to clinical applications.

Biomarker Discovery and Validation Workflows

Comprehensive Protocol 1: Multi-Omics Analysis for MAFLD Biomarker Discovery

Sample Preparation and Data Generation

- Patient Cohort Selection: Recruit MAFLD patients and controls with detailed phenotyping (anthropometrics, metabolic parameters, liver histology)

- Tissue Collection: Obtain liver biopsies for bulk RNA-seq, single-cell RNA-seq, and spatial transcriptomics

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Perform RNA sequencing using appropriate platforms (Illumina for bulk RNA-seq, 10x Genomics for single-cell RNA-seq, Visium for spatial transcriptomics)

Computational Analysis

- Differential Expression Analysis: Identify significantly dysregulated genes between MAFLD and control samples using appropriate statistical thresholds (FDR < 0.05, log2FC > 1)

- Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA): Construct gene modules and identify glycolysis-correlated key genes

- Immune Infiltration Analysis: Utilize single-cell and spatial transcriptomics to characterize immune cell populations and interactions

- Machine Learning Application: Employ multiple models (random forest, SVM, etc.) to identify feature genes and predict MAFLD status

Experimental Validation

- External Cohort Validation: Confirm key gene expression patterns in independent patient cohorts

- In Vivo Models: Utilize methionine choline-deficient diet murine models to validate biomarker expression and functional significance

- Spatial Localization: Verify cellular colocalization of key biomarkers using immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence [5]

Comprehensive Protocol 2: DNA Methylation Biomarker Studies for T2D

Study Design Considerations

- Population Selection: Include diverse populations, particularly Indigenous communities disproportionately affected by T2D

- Sample Type: Peripheral blood (most common), pancreatic β-cells (when available), or other relevant tissues

- Longitudinal Sampling: When possible, collect samples at multiple timepoints to establish temporal relationships

Laboratory Methods

- DNA Extraction: High-quality DNA isolation using standardized kits with quality control (spectrophotometry, fluorometry)

- Bisulfite Conversion: Treat DNA with bisulfite to convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils while preserving methylated cytosines

- Methylation Profiling:

- Microarray-Based: Illumina EPIC arrays for cost-effective genome-wide coverage of ~850,000 CpG sites

- Sequencing-Based: Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing for comprehensive coverage or targeted bisulfite sequencing for specific regions

- Validation: Pyrosequencing or targeted bisulfite sequencing for confirmation of significant CpG sites

Data Analysis

- Quality Control: Remove poor-quality probes, correct for batch effects, check for sample outliers

- Differential Methylation Analysis: Identify significantly differentially methylated positions/regions between cases and controls

- Functional Annotation: Associate methylation changes with genomic features (promoters, enhancers, gene bodies)

- Integration: Correlate methylation patterns with gene expression data when available [6]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for CRHM Syndrome Biomarker Studies

| Category | Specific Products/Platforms | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptomics Platforms | Illumina RNA-seq [5] | Bulk gene expression analysis | Genome-wide expression profiling |

| 10x Genomics Single-Cell RNA-seq [5] | Single-cell resolution transcriptomics | Cellular heterogeneity analysis | |

| Visium Spatial Transcriptomics [5] | Tissue spatial gene expression mapping | Maintains spatial context of gene expression | |

| Epigenetics Tools | Illumina EPIC Methylation Arrays [6] | DNA methylation profiling | ~850,000 CpG sites coverage |

| Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing [6] | Comprehensive methylation analysis | Single-base resolution genome-wide | |

| Targeted bisulfite sequencing [6] | Validation of specific CpG sites | Cost-effective for specific regions | |

| Proteomics/Biomarker Assays | ELISA-based suPAR assays [2] | Quantitative suPAR measurement | High sensitivity and specificity |

| GDF-15 immunoassays [5] | GDF-15 quantification in plasma/serum | Research-use-only validated | |

| Mass spectrometry-based assays [7] | Protein/peptide quantification in diabetes | High precision and accuracy | |

| Animal Models | Methionine choline-deficient diet models [5] | MAFLD/MASH research | Recapitulates human disease features |

| High-fat diet rodent models [1] | Obesity and insulin resistance studies | Induces metabolic syndrome features | |

| Computational Tools | WGCNA R package [5] | Gene co-expression network analysis | Identifies correlated gene modules |

| Seurat/Single-cell analysis tools [5] | Single-cell RNA-seq data analysis | Comprehensive scRNA-seq processing |

Diagram Title: Biomarker Discovery Workflow for CRHM Syndrome

Diagnostic Staging and Clinical Translation

The evolution from MetS to CRHM syndrome has been accompanied by more sophisticated staging systems that enable better risk stratification and targeted interventions.

CRHM Syndrome Staging Framework

Table 4: Proposed Staging System for CRHM Syndrome

| Stage | Definition | Clinical Features | Management Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 0 | No CRHM risk factors | No overweight/obesity, metabolic risk factors, CKD, MASLD, or CVD | Preventive lifestyle strategies |

| Stage I | Excess and/or dysfunctional adiposity | Stage Ia: Overweight (BMI ≥25 kg/m²) or high-normal waist circumference; Stage Ib: Obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m²) or abdominal obesity; Stage Ic: Dysfunctional adiposity with prediabetes | Weight management, dietary intervention, physical activity |

| Stage II | Metabolic risk factors, CKD, or MASLD | One or more of: hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, MetS, diabetes mellitus; Low-moderate risk CKD; MASLD with fibrosis stage F0-F1 | Risk factor control, monitoring for progression |

| Stage III | Subclinical CVD | Subclinical ASCVD or stage B HF among individuals with Stage I/II risk factors; Risk equivalents: very high 10-year cardiovascular risk, high/very high-risk CKD, MASLD with fibrosis stage F2-F4 | Intensive risk factor modification, consider organ-protective therapies |

| Stage IV | Clinical CVD | Clinical CVD (ASCVD, HF) among individuals with Stage I/II risk factors; Stage IVa: Without end-stage renal disease or cirrhosis; Stage IVb: With end-stage renal disease and/or cirrhosis | Multidisciplinary care, advanced disease management [4] |

Therapeutic Implications and Emerging Treatments

Novel therapeutic classes have demonstrated benefits across multiple organ systems in CRHM syndrome, supporting the integrated framework. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), initially developed for glycemic control, have shown significant improvements in cardiovascular and renal outcomes in patients with and without diabetes [1]. Similarly, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) and combined gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 receptor agonists demonstrate multi-organ protective effects through antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-fibrotic mechanisms; enhancement of myocardial energetics; decreased neurohormonal activation; improved endothelial function; and reduced arterial stiffness [1].

These therapeutic advances align with the CRHM model by targeting shared pathophysiological pathways rather than individual disease states. Their mechanisms support the interconnected nature of cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, and metabolic systems and provide clinical validation of the syndrome concept.

Future Directions and Research Implications

The conceptual evolution from MetS to CRHM syndrome continues to shape research priorities and methodological approaches in several key areas:

Biomarker Innovation and Validation

Future biomarker development requires addressing several critical challenges. Emerging biomarkers must be validated across diverse populations, including Indigenous communities who experience disproportionate T2D burden but remain underrepresented in research [6]. For example, American-Indian young people experience more than double the burden of T2D compared to American young people overall (46.0 vs. 17.9 per 100,000) [6]. Biomarker discovery in these populations must be conducted ethically with community engagement and respect for data sovereignty.

Advanced technologies including sequencing-based DNA methylation analysis, single-cell multi-omics, and spatial transcriptomics will enable more comprehensive biomarker discovery [5] [6]. The transition from microarray to sequencing-based approaches for DNA methylation analysis provides improved genome-wide coverage and better capture of genetic and environmental complexities in T2D [6].

Precision Medicine and Population-Specific Approaches

The future of CRHM syndrome management lies in precision medicine approaches that account for individual variability in genetics, environment, and lifestyle. This requires:

- Development of integrated biomarker panels that combine traditional and novel biomarkers for improved risk stratification

- Refinement of staging systems to incorporate biomarker data for more dynamic progression monitoring

- Implementation of standardized protocols for biomarker testing and interpretation to ensure clinical utility

- Education and training for healthcare providers to effectively utilize biomarker data in clinical decision-making [5]

Interdisciplinary Research Models

Addressing the complexity of CRHM syndrome necessitates breaking down traditional silos between cardiology, nephrology, hepatology, and endocrinology. Future research should embrace:

- Integrated experimental models that capture multi-organ interactions rather than studying systems in isolation

- Clinical trial designs that evaluate outcomes across multiple organ systems simultaneously

- Collaborative research networks that bring together specialists from different disciplines

- Shared data repositories that enable comprehensive analysis of interconnected physiological systems

The conceptual evolution from Metabolic Syndrome to Cardiovascular-Renal-Hepatic-Metabolic syndrome represents a paradigm shift in understanding interconnected metabolic disorders. This progression reflects an increasingly sophisticated appreciation of the shared pathophysiological mechanisms driving multisystemic dysfunction, particularly relevant in the context of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes research. The CRHM framework acknowledges the intricate interactions between cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, and metabolic systems, moving beyond organ-specific approaches to embrace a more holistic understanding of disease pathogenesis.

For researchers and drug development professionals, this evolving conceptual landscape presents both challenges and opportunities. The development and validation of novel biomarkers—from traditional circulating markers to epigenetic signatures and multi-omics profiles—are essential for advancing early detection, risk stratification, and therapeutic monitoring. Emerging therapeutic classes with multi-organ protective effects provide clinical validation of the CRHM concept and offer promising avenues for intervention. As research methodologies continue to advance, embracing integrated, interdisciplinary approaches will be crucial for addressing the complex pathophysiology of CRHM syndrome and developing effective, personalized strategies for prevention and treatment.

The global rise in metabolic syndrome (MetS) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) represents a critical public health challenge, driven by the intertwined pathophysiological forces of insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, and oxidative stress [8] [9]. These core mechanisms create a self-sustaining cycle that promotes disease progression and leads to serious complications, including cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative disorders, and cancer [10] [11]. Understanding these interconnected pathways is paramount for developing novel biomarkers and targeted therapeutic strategies. This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of these mechanisms, framed within the context of advanced biomarker research for MetS and T2DM, offering a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals.

Molecular Mechanisms of Insulin Resistance

Insulin Signaling Pathway and Disruption Mechanisms

Insulin resistance (IR) is a state of diminished responsiveness to insulin stimulation in key target tissues—primarily liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue [12]. The canonical insulin signaling pathway is initiated when insulin binds to its cell-surface receptor (INSR), triggering a phosphorylation cascade that involves the recruitment and tyrosine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate (IRS) proteins, activation of PI3-kinase (PI3K), and subsequent activation of AKT isoforms [12].

The table below summarizes key defects in the insulin signaling pathway that contribute to insulin resistance:

Table 1: Defects in Insulin Signaling Pathways Leading to Insulin Resistance

| Signaling Component | Defect Type | Functional Consequence | Associated Tissues |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin Receptor (INSR) | Decreased surface content; Reduced kinase activity | Impaired insulin binding and signal initiation [12] | Liver, Muscle, Adipose |

| IRS Proteins | Reduced expression; Serine phosphorylation | Decreased PI3K binding and activation [12] | Muscle, Liver |

| PI3K | Inhibited expression/activity | Attenuated AKT activation [12] | Muscle, Liver |

| AKT | Impaired phosphorylation (Ser473) | Reduced downstream signaling [12] | Muscle, Liver |

| GLUT4 | Impaired translocation | Decreased insulin-stimulated glucose uptake [12] | Muscle, Adipose |

Experimental Models for Studying Insulin Resistance

Investigating these complex mechanisms requires robust experimental methodologies. The following protocol outlines a standard approach for assessing insulin sensitivity in vitro and in vivo.

Table 2: Core Experimental Protocol for Insulin Resistance Research

| Experimental Stage | Key Methodologies | Measured Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| 1. In Vivo Assessment | Hyperinsulinemic-Euglycemic Clamp (Gold Standard) [11] | Whole-body insulin sensitivity; Tissue-specific glucose disposal rates |

| Homeostatic Model Assessment (HOMA-IR) [11] | Fasting insulin and glucose levels to estimate IR | |

| Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) [11] | Postprandial glucose metabolism and insulin response | |

| 2. In Vitro Models | Cell culture (e.g., L6 myotubes, 3T3-L1 adipocytes, HepG2 hepatocytes) treated with high glucose/FFA [12] | Insulin-stimulated glucose uptake; IRS/PI3K/AKT phosphorylation |

| 3. Molecular Analysis | Western Blot; Immunoprecipitation [12] | Protein expression and phosphorylation status in signaling pathways |

| 4. Advanced 'Omics | Metabolomics (NMR, Mass Spectrometry) [13] | Circulating metabolites (e.g., BCAAs, triglycerides, HDL) |

Chronic Inflammation as a Metabolic Driver

Inflammatory Pathways in Metabolic Disease

Chronic, low-grade inflammation is a cornerstone of metabolic dysfunction, characterized by persistent immune activation and elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines [10] [14]. Adipose tissue, particularly in visceral obesity, acts as a primary endocrine organ, releasing adipokines, cytokines, and chemokines that sustain this inflammatory state [5] [15]. Key mediators include Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), and C-Reactive Protein (CRP) [14] [15].

These inflammatory molecules directly interfere with insulin signaling. TNF-α, for instance, promotes serine phosphorylation of IRS-1, rendering it a poorer substrate for the INSR and targeting it for degradation, thereby disrupting the insulin signal transduction cascade [14]. This creates a direct molecular link between inflammation and insulin resistance.

Biomarkers of Metabolic Inflammation

The table below summarizes key inflammatory biomarkers relevant to MetS and T2DM research:

Table 3: Key Inflammatory Biomarkers in Metabolic Syndrome and T2DM

| Biomarker | Cellular Origin | Pathophysiological Role | Association with IR/MetS |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | Macrophages, Adipocytes | Induces serine phosphorylation of IRS-1; Suppresses GLUT4 expression [14] | Strongly positive; levels correlate with obesity and IR [14] |

| IL-6 | Immune Cells, Adipocytes (~30%) | Hepatic CRP synthesis; Impairs insulin signaling [14] | Elevated in T2DM; predicts disease progression [14] |

| CRP | Liver (induced by IL-6) | Acute-phase reactant; Non-specific marker of inflammation [14] | Independent predictor of T2DM and CVD risk [14] |

| Leptin | Adipocytes | Regulates appetite/satiety; Pro-inflammatory at high levels [5] | Increases with adiposity (leptin resistance) [5] |

| Adiponectin | Adipocytes | Enhances insulin sensitivity; Anti-inflammatory [5] | Reduced in obesity and IR [5] |

| GDF-15 | Multiple tissues under stress | Member of TGF-β superfamily; cellular stress response marker [15] | Associated with obesity, IR, and diabetic traits [15] |

Oxidative Stress and Redox Imbalance

Oxidative stress (OS) arises from an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the body's antioxidant defense capabilities [16]. In metabolic diseases, chronic nutrient excess (glucose and lipids) drives mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS overproduction through multiple pathways, including the polyol pathway, advanced glycation end-product (AGE) formation, and activation of protein kinase C (PKC) [16] [14].

ROS directly damage cellular components—lipids, proteins, and DNA—and act as signaling molecules that disrupt insulin action. Specifically, ROS can inhibit insulin signaling by oxidizing critical components in the pathway, further exacerbating insulin resistance [16] [14]. This establishes a vicious cycle where hyperglycemia-induced ROS impairs insulin secretion and action, leading to worsened hyperglycemia.

Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress

Clinically validated biomarkers are essential for quantifying oxidative stress. The table below details key OS biomarkers and their significance in metabolic disease.

Table 4: Established and Emerging Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress

| Biomarker Category | Specific Marker | Significance / Mechanism | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid Peroxidation | F2-isoprostanes | Gold standard; stable peroxidation products of arachidonic acid [16] | Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) |

| DNA Damage | 8-Hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) | Oxidative modification of guanine in DNA; marker of genomic damage [16] | ELISA, Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) |

| Antioxidant Enzymes | Superoxide Dismutase (SOD), Glutathione Peroxidase (GPX1), Catalase (CAT) | Key enzymatic defenses; their activity/levels often altered in disease [14] | Activity assays, ELISA |

| Glycated Proteins | HbA1c | Indirect marker of oxidative burden; reflects sustained hyperglycemia [5] | High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) |

Interplay and Amplification Loops

The pathophysiological triad of IR, inflammation, and OS does not operate in isolation. Instead, they engage in complex crosstalk and form positive feedback loops that drive metabolic decline.

- Inflammation → Oxidative Stress: Pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α can activate NADPH oxidases (NOX), major enzymatic sources of ROS, thereby increasing oxidative stress [16].

- Oxidative Stress → Inflammation: ROS activate redox-sensitive transcription factors, such as Nuclear Factor-kappa B (NF-κB), which in turn upregulate the expression of pro-inflammatory genes (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6), perpetuating the inflammatory state [8] [16].

- Adipose Tissue as a Hub: Dysfunctional, expanded adipose tissue is a primary site for this crosstalk, releasing both inflammatory cytokines and non-esterified fatty acids (NEFAs). Elevated NEFAs contribute to lipotoxicity, further promoting ectopic fat deposition, mitochondrial dysfunction, ROS production, and IR in liver and muscle [12] [11].

The Researcher's Toolkit

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Advancing research in this field relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details essential solutions for investigating these core mechanisms.

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Core Metabolic Mechanisms

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Application / Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Based Assay Kits | Glucose Uptake Assay Kits (e.g., fluorescent 2-NBDG) | Quantify insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in cultured cells (myotubes, adipocytes) [12] |

| ELISA Kits | Phospho-specific ELISAs (e.g., p-AKT, p-IRS-1); Cytokine ELISAs (TNF-α, IL-6, Adiponectin); OS Marker ELISAs (8-OHdG) | Measure protein phosphorylation, inflammatory markers, and oxidative damage in cell lysates, tissue homogenates, or serum/plasma [14] |

| Metabolomic Panels | NMR-based metabolomic profiling (e.g., Nightingale Health panel) | Quantify 100+ circulating metabolites (lipids, fatty acids, glycoproteins, amino acids) for network analysis [13] |

| Signal Pathway Modulators | PI3K Inhibitors (e.g., LY294002); AKT Inhibitors; TNF-α neutralizing antibodies; Nrf2 activators | Chemically probe specific nodes in insulin, inflammatory, and antioxidant signaling pathways [12] [16] |

| Animal Models | High-Fat Diet Fed Mice; ob/ob and db/db Mice; ZDF Rats | Model human MetS and T2DM to study disease progression and therapeutic interventions in vivo [8] |

Emerging Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets

The application of omics technologies is revealing novel biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets. Branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), total triglycerides, and large HDL cholesterol have been identified as central hubs in the T2DM risk metabolome network, with BCAA levels serving as potent early indicators in pre-T2DM individuals [13]. The inflammatory glycoprotein GlycA demonstrates female-specific risk associations [13]. Non-coding RNAs, such as serum miR-484, are also being investigated for their role in glucose metabolism and as potential diagnostic markers [15].

Emerging therapeutic strategies focus on breaking the cycles of dysfunction. These include mitochondria-targeted antioxidants (e.g., MitoQ), Nrf2 activators to restore redox balance, specific NOX isoform inhibitors, and interventions aimed at modulating the gut microbiota to reduce systemic inflammation and OS [8] [16].

Cardiometabolic diseases represent an escalating global health crisis, slowing or even reversing earlier declines in cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality [1] [17]. The understanding of metabolic disorders has evolved dramatically from isolated disease models to a comprehensive framework recognizing intricate inter-organ communication. Cardiovascular-Renal-Hepatic-Metabolic (CRHM) syndrome has emerged as a conceptual framework describing interconnected pathophysiological mechanisms across multiple organ systems [2] [18]. While not yet a formal diagnosis, this paradigm provides valuable insights into shared disease processes and therapeutic strategies for addressing conditions that collectively intensify disease progression, elevating the risk of multi-organ dysfunction, morbidity, and mortality [2].

This syndromic concept extends the American Heart Association's Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic (CKM) syndrome model by incorporating the liver's pivotal role in systemic metabolic dysfunction [17]. The proposed CRHM syndrome is defined as "a systemic disorder that leads to parallel multiorgan dysfunction driven by shared pathophysiological mechanisms, including metabolic inflammation (meta-inflammation) and dysregulation, particularly insulin resistance" [2] [18]. This framework captures the clinical reality that conditions once managed separately—obesity, type 2 diabetes (T2DM), atherosclerotic CVD, heart failure (HF), chronic kidney disease (CKD), and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)—are interconnected disorders sharing common pathophysiological pathways [1] [17].

Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Multi-Organ Cross-Talk

The pathophysiology of CRHM syndrome is driven by multifaceted interactions of unified mechanisms, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of multi-organ dysfunction. At its core, chronic inflammation acts as the foundation, initiating tissue damage through pro-inflammatory cytokines, immune activation, and fibrotic changes [2] [19]. Insulin resistance fuels this process, worsening metabolic dysfunction, hyperglycemia, and lipid dysregulation, which further strain the cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, and metabolic systems [2]. As the condition progresses, oxidative stress amplifies cellular injury, mitochondrial dysfunction, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, worsening organ failure [2]. Finally, endothelial dysfunction impairs vascular integrity, increases arterial stiffness, and perpetuates ischemic injury, creating a vicious cycle of multi-organ damage [2] [19].

Central Role of Adipose Tissue Dysfunction and Inflammation

Obesity-induced adipose tissue dysfunction initiates a chronic low-grade inflammatory state, or "meta-inflammation," which plays a pivotal role in developing cardio-renal-metabolic diseases [18] [19]. As adipose tissue expands, hypoxia and cellular stress trigger adipocyte death and recruit pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages, replacing anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages [18]. This phenotypic shift exacerbates inflammation and disrupts metabolic homeostasis. M1 macrophages secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α and IL-6, which impair insulin receptor signaling by activating serine kinases like c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and inhibitor of kappa B kinase-beta (IKK-β) [18]. These kinases phosphorylate insulin receptor substrates (IRS), reducing glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4)-mediated glucose uptake and promoting insulin resistance [18].

The dysfunctional adiposity and ectopic fat deposition are central drivers of this pathophysiology [1]. When subcutaneous adipose tissue storage capacity is exceeded, lipids accumulate in visceral deposits and ectopic sites including the liver, skeletal muscle, pancreas, renal sinus, and even intramyocardial compartments [1]. This ectopic fat accumulation leads to lipotoxicity—a toxic overload of lipids in non-adipose tissues—provoking organ-specific fibro-inflammatory responses that contribute to systemic metabolic dysfunction and multi-organ damage [1].

Key Signaling Pathways in Inter-Organ Communication

Mechanistic investigations have revealed that aberrant activation of several signaling pathways constitutes a complex inflammatory regulatory network facilitating inter-organ crosstalk [19]. These pathways establish positive feedback loops among the heart, kidneys, liver, and metabolic tissues, amplifying pathological processes including oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, and fibrosis in a cascading manner [19]. The following diagram illustrates the core inflammatory signaling pathways and their interactions in CRHM syndrome:

The NF-κB pathway serves as a master regulator of inflammation, activated by cytokines, oxidative stress, and metabolic danger signals [19]. Once activated, it triggers transcription of numerous pro-inflammatory genes, creating a feed-forward loop that sustains chronic inflammation across organ systems. The JAK-STAT pathway transmits signals from cytokine receptors to the nucleus, modulating immune cell differentiation and inflammatory responses [19]. Simultaneously, PI3K-AKT pathway dysregulation impairs insulin signaling, creating a bridge between inflammatory and metabolic disturbances [19]. These pathways facilitate coordinated damage across cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, and metabolic systems, establishing the molecular basis for CRHM syndrome progression.

Organ-Specific Pathological Consequences

Cardiovascular System

Cardiac manifestations in CRHM syndrome include atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), and diabetic cardiomyopathy [19] [17]. Cardiovascular damage results from endothelial dysfunction, increased arterial stiffness, cardiac lipotoxicity, fibrosis, and impaired myocardial energetics [1] [17]. MASLD independently increases cardiovascular mortality risk (hazard ratio 1.30) and non-fatal CVD events (HR 1.40) [17].

Renal System

Chronic kidney disease in CRHM syndrome develops through multiple interconnected pathways: hemodynamic changes from systemic hypertension, glomerular hyperfiltration in diabetes, inflammatory glomerular and tubulointerstitial damage, and renal sinus lipid accumulation [19] [1]. Leptin, elevated in obesity, induces glomerulosclerosis and fibrosis while promoting oxidative stress in renal tubular epithelial cells [19].

Hepatic System

MASLD represents the hepatic manifestation of metabolic dysregulation, characterized by triglyceride accumulation in hepatocytes (>5% steatosis) [17]. Progression to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) involves hepatocyte injury, inflammation, and fibrosis driven by lipotoxicity and inflammatory cytokines [17]. The liver contributes to systemic insulin resistance and dyslipidemia, creating bidirectional relationships with other organ systems [17].

Emerging Biomarkers for CRHM Syndrome

Traditional inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) have limitations in predicting long-term disease progression in CRHM syndrome [2] [18]. Emerging biomarkers offer novel insights into systemic disease mechanisms and potential for personalized medicine approaches. The following table summarizes key traditional and emerging biomarkers with their clinical associations and research applications:

Table 1: Biomarkers for Cardiovascular-Renal-Hepatic-Metabolic Syndrome

| Biomarker Category | Specific Biomarker | Pathophysiological Role | Organ System Associations | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Inflammatory Markers | CRP | Acute phase reactant, general inflammation marker | Cardiovascular risk assessment | Limited specificity for long-term outcomes [2] |

| IL-6 | Pro-inflammatory cytokine | Systemic inflammation, atherosclerosis | Therapeutic target in clinical trials [19] | |

| TNF-α | Pro-inflammatory cytokine | Insulin resistance, endothelial dysfunction | Mechanism studies [18] [19] | |

| Emerging Biomarkers | suPAR | Systemic chronic inflammation, immune activation | CKD progression, atherosclerosis, coronary artery calcification [2] [18] | Predictive marker for renal and cardiovascular outcomes [2] |

| Galectin-3 | Fibrosis and inflammation regulation | Cardiac remodeling, hepatic fibrosis, kidney disease [2] [18] | Prognostic marker in heart failure and liver disease [2] | |

| GDF-15 | Mitochondrial dysfunction, cardiovascular aging | Metabolic stress, cardiovascular events [2] [18] | Risk stratification for cardiovascular aging [2] | |

| miR-126 | Angiogenesis, vascular integrity | Endothelial dysfunction, atherosclerosis [2] | Vascular health assessment [2] | |

| miR-423-5p | Heart failure progression | Myocardial stress, cardiac remodeling [2] | Heart failure monitoring [2] | |

| Metabolic Biomarkers | TyG-BMI | Insulin resistance surrogate | CVD risk in CKM syndrome [19] | Epidemiological research [19] |

| Stress Hyperglycemia Ratio (SHR) | Glycemic variability | All-cause mortality in CKM stages 0-3 [19] | Prognostic biomarker [19] |

Promising Novel Biomarker Profiles

Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) has emerged as a stable and predictive biomarker of systemic chronic inflammation, with strong associations with renal disease progression, cardiovascular risk, and metabolic disorders [2] [18]. Elevated suPAR levels correlate with CKD, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery calcification, with genetic studies linking suPAR to proinflammatory monocyte activation and vascular dysfunction [2] [18].

Galectin-3, a key regulator of fibrosis and inflammation across multiple organ systems, is strongly associated with cardiac remodeling, hepatic fibrosis, and kidney disease progression [2] [18]. Elevated levels predict higher mortality in heart failure and correlate with liver fibrosis severity [2].

Growth Differentiation Factor-15 (GDF-15) is implicated in mitochondrial dysfunction and cardiovascular aging, with elevated levels observed in metabolic stress and cardiac injury [2] [18]. This biomarker responds to cellular stress and inflammation across organ systems.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) including miR-126 (vascular integrity) and miR-423-5p (heart failure progression) show promise as biomarkers with altered expression patterns correlating with atherosclerosis, insulin resistance, and cardiac dysfunction [2] [18]. These regulatory RNAs offer potential as both biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Experimental Models and Methodologies

In Vivo Models of Multi-Organ Disease

Animal models reproducing CRHM syndrome pathophysiology typically combine genetic predispositions with dietary interventions. The following table outlines key experimental approaches for modeling CRHM syndrome:

Table 2: Experimental Models for CRHM Syndrome Research

| Model Category | Specific Model | Induction Method | CRHM Manifestations | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diet-Induced Models | High-Fat, High-Fructose, High-Cholesterol Diet | 12-24 weeks special diet | Obesity, insulin resistance, hepatic steatosis, early cardiac/renal dysfunction [20] | Disease progression studies, therapeutic interventions |

| Western Diet + NASH-inducing components | High-fat diet with added cholesterol/fructose | Progressive MASLD/MASH, renal impairment, cardiovascular changes [20] | Liver-focused CRHM investigations | |

| Genetic Models | Leptin-deficient (ob/ob) or leptin receptor-deficient (db/db) mice | Natural mutations or genetic engineering | Severe obesity, insulin resistance, hepatic steatosis, cardiomyopathy [20] | Metabolic component studies |

| ApoE-/- or LDLR-/- mice with metabolic challenge | Genetic ablation + high-fat diet | Atherosclerosis, insulin resistance, hepatic steatosis [20] | Cardiovascular-metabolic interactions | |

| Combination Models | CKM syndrome mouse model | High-fat diet + low-dose streptozotocin + unilateral nephrectomy | Insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, renal dysfunction, cardiac fibrosis [20] | Comprehensive multi-organ studies |

| Aged mice with metabolic challenge | Aging + high-fat diet | Age-related multi-organ dysfunction, insulin resistance [20] | Aging-CRHM interactions |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following research reagents are critical for investigating CRHM syndrome mechanisms and evaluating therapeutic interventions:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRHM Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Reagents | Research Application | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Models | Primary hepatocytes, adipocytes, renal tubular epithelial cells, endothelial cells | In vitro mechanistic studies | Cell-type specific signaling studies [19] |

| Immortalized cell lines (HepG2, THP-1, HK-2) | High-throughput screening | Therapeutic candidate evaluation [19] | |

| Antibodies for Signaling Pathways | Phospho-specific antibodies (p-NF-κB, p-AKT, p-STAT3) | Western blot, immunohistochemistry | Pathway activation assessment [19] |

| Cytokine antibodies (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) | ELISA, flow cytometry | Inflammatory mediator quantification [19] | |

| Fibrosis markers (α-SMA, collagen I, galectin-3) | Immunohistochemistry, Western blot | Tissue remodeling evaluation [2] [19] | |

| Molecular Biology Tools | miRNA inhibitors/mimics (miR-126, miR-423-5p) | Transfection experiments | Functional miRNA studies [2] |

| qPCR assays for emerging biomarkers (suPAR, GDF-15, Galectin-3) | Gene expression analysis | Biomarker expression profiling [2] | |

| RNA-seq libraries | Transcriptomic profiling | Global gene expression patterns [20] | |

| Metabolic Assays | Glucose uptake assays (2-NBDG) | Cellular metabolism studies | Insulin sensitivity assessment [19] |

| Mitochondrial function kits (Seahorse) | Bioenergetics profiling | Metabolic flux analysis [19] | |

| Lipid quantification kits (triglycerides, free fatty acids) | Hepatic and plasma lipid measurement | Lipotoxicity assessment [19] |

Standardized Experimental Protocol for CRHM Assessment

The following workflow provides a comprehensive methodological approach for evaluating multi-organ cross-talk in experimental models:

Week 0: Baseline Characterization

- Metabolic parameters: Body weight, fasting blood glucose, oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), insulin tolerance test (ITT), plasma lipid profile

- Cardiovascular assessment: Blood pressure measurement (tail-cuff or telemetry), echocardiography for cardiac structure and function

- Renal function: Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR), plasma creatinine

- Hepatic status: Plasma ALT, AST measurements

Week 4-24: Intervention Period (depending on model)

- Dietary intervention: High-fat diet (45-60% kcal from fat) + high fructose (10-20%) in drinking water

- OR genetic model maintenance with standard monitoring

- Bi-weekly metabolic parameter assessment

Week 24: Terminal Endpoint Analyses

- Tissue collection (heart, kidney, liver, adipose tissue) with division for:

- Histopathology (formalin fixation)

- Molecular analyses (flash-freezing in liquid N₂)

- Primary cell isolation (immediate processing)

- Comprehensive tissue analysis:

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

Emerging Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Multi-Organ Pathways

Recent advances in pharmacotherapy have revealed several drug classes with pleiotropic effects across multiple organ systems in CRHM syndrome. These therapies target shared pathophysiological pathways rather than individual disease entities, representing a paradigm shift in management approach.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, initially developed for glycemic control, have demonstrated significant benefits across cardiovascular, renal, and metabolic domains [1] [17]. Regardless of diabetes status, empagliflozin and dapagliflozin improve outcomes in heart failure and chronic kidney disease [1]. Proposed mechanisms include antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-fibrotic effects; enhancement of myocardial energetics; decreased neurohormonal activation; improved endothelial function; promoted vasodilation; reduced arterial stiffness; and increased natriuresis [1].

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) and dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 receptor agonists provide multi-organ protection through weight loss, glycemic control, and direct cardiorenal benefits [2] [1] [17]. These agents demonstrate direct cardiac and kidney benefits even within short-term trials [21].

Nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (e.g., finerenone) target fibrosis and inflammation across organ systems, showing particular promise for renal and cardiovascular protection in CRHM syndrome [1] [21].

The following table compares the multi-organ benefits of these therapeutic classes:

Table 4: Multi-Organ Benefits of Emerging CRHM Therapies

| Therapeutic Class | Cardiovascular Benefits | Renal Benefits | Hepatic Benefits | Metabolic Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT2 Inhibitors | Reduced HF hospitalizations, improved outcomes in HFrEF/HFpEF [1] | Slowed CKD progression, reduced albuminuria [1] | Potential improvement in hepatic steatosis [17] | Glycemic control, weight reduction, blood pressure lowering [1] |

| GLP-1 Receptor Agonists | Reduced MACE, atherosclerotic events [1] | Reduced albuminuria, slowed eGFR decline [1] | Improvement in MASLD metrics [17] | Significant weight reduction, glycemic control [1] |

| GIP/GLP-1 Receptor Agonists | Cardiovascular outcome trials ongoing [2] | Renal outcomes under investigation [2] | Significant improvement in MASH histology [2] | Superior weight reduction vs. GLP-1 RAs alone [2] |

| Nonsteroidal MRAs | Reduced CV death/HF hospitalization [1] | Slowed CKD progression, reduced albuminuria [1] | Anti-fibrotic effects in liver [21] | Modest metabolic improvements [1] |

Biomarker-Guided Therapeutic Approaches

Emerging biomarkers not only aid in early detection but also guide targeted interventions in CRHM syndrome [2]. Elevated levels of specific biomarkers may support personalized therapeutic decisions:

- Elevated suPAR levels: May indicate heightened systemic inflammation favoring SGLT2 inhibitors for cardiorenal protection [2]

- Increased galectin-3: Suggests active fibrotic processes potentially responsive to nonsteroidal MRAs [2]

- Rising GDF-15: Indicates mitochondrial dysfunction and metabolic stress potentially addressed by GLP-1RAs [2]

- Altered miRNA patterns: May identify specific pathway activations for targeted therapies [2]

Future Research Directions

The complex interplay of multi-organ dysfunction in CRHM syndrome presents both challenges and opportunities for future research. Multi-omics approaches (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) combined with machine learning may better capture common underlying mechanisms and inter-organ crosstalk [20]. There is a pressing need for more inclusive clinical trials that examine contributions of multimorbidity and incorporate multi-organ endpoints [20]. Additionally, anti-inflammatory therapies specifically targeting the inflammatory co-mechanisms of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease represent a promising frontier [21].

The integration of emerging biomarkers into clinical trial designs may enable better patient stratification and monitoring of treatment responses. Furthermore, understanding how social determinants of health and disparities influence CRHM syndrome progression requires focused investigation [21].

The conceptual evolution from isolated metabolic disorders to the comprehensive CRHM syndrome framework reflects growing appreciation of intricate multi-organ cross-talk. This paradigm recognizes that conditions affecting the cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, and metabolic systems share common pathophysiological roots including chronic inflammation, insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction. The emerging biomarker landscape offers promising tools for early detection, risk stratification, and personalized therapeutic approaches. Simultaneously, novel therapeutic classes with pleiotropic effects across organ systems represent a paradigm shift in management strategy. Future research integrating multi-omics technologies, comprehensive clinical trials, and disparity-focused investigations will further advance our understanding and management of these interconnected conditions. Viewing these conditions as an integrated whole rather than discrete entities fosters a more holistic management approach essential for addressing the ongoing cardiometabolic health crisis.

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) represent interconnected global health challenges characterized by insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, and metabolic dysregulation. The pathophysiology of these conditions is orchestrated by complex intracellular signaling networks that integrate genetic, environmental, and metabolic cues. Among these, three signaling pathways have emerged as critical regulators and potential biomarker sources: the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K-Akt) pathway, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade, and the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) innate immune signaling axis. These pathways not only govern core metabolic processes but also exhibit cross-talk that creates a signaling network whose dysregulation propagates metabolic dysfunction across tissues. This technical review examines the molecular architecture, experimental evidence, and biomarker potential of these pathways within the context of MetS and T2DM research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with current methodological frameworks for investigating these critical signaling networks.

PI3K-Akt Signaling: Central Regulator of Metabolic Homeostasis

Pathway Architecture and Metabolic Functions

The PI3K-Akt pathway serves as the primary intracellular signaling cascade for insulin-mediated metabolic regulation, coordinating glucose uptake, lipid metabolism, and protein synthesis. Upon insulin binding to its receptor, PI3K phosphorylates membrane phosphatidylinositol lipids, generating second messengers that recruit and activate Akt through phosphorylation at Thr308 and Ser473 residues. Activated Akt then propagates metabolic signals through downstream effectors including mTOR, GSK-3β, and FOXO transcription factors, promoting GLUT4 translocation to the plasma membrane and hepatic glycogen synthesis while inhibiting gluconeogenesis and lipolysis.

Dysregulation in Metabolic Syndrome and T2DM

Insulin resistance, a fundamental defect in both MetS and T2DM, manifests as impaired PI3K-Akt signaling. Recent human tissue research reveals distinctive expression patterns in adipose depots, with visceral adipose tissue (VAT) PI3K expression showing strong positive associations with hyperinsulinemia (β = 8.802, P = 0.008) and insulin resistance (β = 7.710, P = 0.028) [22]. Similarly, VAT Akt expression correlates with hyperinsulinemia (β = 6.684, P = 0.003) and insulin resistance (β = 5.296, P = 0.027) [22]. The pathway's negative regulator, PTEN, demonstrates an inverse relationship with insulin resistance (β = -4.475, P = 0.021) in subcutaneous adipose tissue [22], highlighting its potential therapeutic targeting value.

Table 1: PI3K-Akt Pathway Gene Expression Associations with Insulin Indices in Human Adipose Tissue

| Gene | Adipose Depot | Associated Metabolic Parameter | Effect Size (β) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI3K | Visceral | Hyperinsulinemia | 8.802 | 0.008 |

| PI3K | Visceral | HOMA-IR | 7.710 | 0.028 |

| Akt | Visceral | Hyperinsulinemia | 6.684 | 0.003 |

| Akt | Visceral | HOMA-IR | 5.296 | 0.027 |

| Akt | Subcutaneous | Fasting Plasma Insulin | 0.128 | 0.048 |

| Akt | Subcutaneous | Hyperinsulinemia | 4.201 | 0.008 |

| PTEN | Subcutaneous | HOMA-IR | -4.475 | 0.021 |

Experimental Assessment Methodologies

Gene Expression Analysis in Human Adipose Tissue: The cross-sectional study design provides a robust methodology for investigating PI3K-Akt pathway activity in metabolic disease [22]. Adipose tissue biopsies (50-100 mg) are obtained during elective abdominal surgery, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80°C. RNA extraction using TRIzol reagent is followed by DNase I treatment to remove genomic DNA. After quality assessment via Nanodrop spectrophotometry (A260/280 ratio) and gel electrophoresis, cDNA synthesis employs commercial kits (e.g., BIOFACT, South Korea). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) using SYBR-Green PCR Master Mix on platforms such as the Corbett Rotor-Gene 6000 with cycling programs established in previous studies [22]. Relative quantitation applies the comparative CT method with GAPDH as the internal control, adhering to MIQE guidelines.

Functional Pathway Interrogation: Beyond gene expression, pathway activity assessment requires phosphorylation-specific immunoblotting for Akt residues (Thr308, Ser473) and downstream targets in tissue lysates from muscle, liver, or adipose tissue. Insulin clamp studies combined with tissue biopsies represent the gold standard for correlating pathway activity with whole-body insulin sensitivity in humans.

MAP Kinase Signaling: Integrating Stress and Metabolic Responses

Pathway Diversity and Metabolic Regulation

The MAPK pathways comprise three major branches: extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38 MAPK. These cascades translate extracellular stimuli into adaptive intracellular responses, with ERK typically activated by growth factors and mitogens, while JNK and p38 respond to cellular stressors including inflammatory cytokines, oxidative stress, and lipotoxicity. In metabolic tissues, MAPK signaling regulates cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and insulin sensitivity, with pathway- and context-specific outcomes.

Pathway Activation in Metabolic Dysfunction

Sustained activation of stress-responsive MAPK branches (JNK and p38) significantly contributes to insulin resistance development. In diabetic kidney disease (DKD), metformin mediates renal protection through MAPK pathway modulation, specifically engaging MAPK1 and MAPK3 (ERK1/2) [23]. Phosphoproteomic analyses reveal metformin's influence on phosphorylation states of MAPK pathway components, with carbohydrate metabolites like D-xylose identified as potential biomarkers for therapeutic monitoring [23]. The resistin/TLR4/miR-155-5p axis in hypothalamic inflammation activates JNK and p38 MAPK signaling, establishing a novel neuroinflammatory pathway that impairs whole-body glucose homeostasis [24].

Experimental Assessment Methodologies

Phosphoproteomic Analysis in Metabolic Tissues: Comprehensive MAPK pathway investigation requires phosphoproteomic approaches [23]. Kidney tissue homogenization is followed by protein extraction and tryptic digestion. Phosphopeptide enrichment employs TiO2 or IMAC columns before LC-MS/MS analysis on high-resolution instruments (e.g., Q-Exactive HF-X). Data processing with MaxQuant or similar platforms identifies phosphorylation sites, with differential phosphorylation analysis between experimental groups (e.g., db/db mice with/without metformin treatment). Functional enrichment analysis (KEGG, GO) reveals pathway-level alterations, with validation through immunoblotting using phospho-specific antibodies for ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), and p38 (Thr180/Tyr182).

Integrated Multi-omics Approach: Network pharmacology predicts metformin-MAPK interactions, with phosphoproteomic validation in target tissues and metabolomic correlation in blood/urine samples [23]. This integrated framework identifies conserved therapeutic targets across species, enhancing translational relevance.

Table 2: MAPK Pathway Components in Metabolic Disease Models

| MAPK Branch | Metabolic Context | Activation State | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERK1/2 (MAPK1/3) | Diabetic Kidney Disease | Modulated by metformin | Renoprotective effects |

| JNK | Hypothalamic Inflammation | Activated by resistin/TLR4 | Insulin resistance, glucose intolerance |

| p38 | Hypothalamic Inflammation | Activated by resistin/TLR4 | Microglial activation, neuroinflammation |

| ERK1/2 | Skeletal Muscle | Redox-sensitive | Impacts insulin sensitivity |

| JNK | Hepatic steatosis | Activated by lipotoxicity | Promotes hepatic insulin resistance |

TLR4 Activation: Bridging Innate Immunity and Metabolic Inflammation

Pathway Mechanism and Metabolic Implications

Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) functions as a pattern recognition receptor that activates innate immune responses upon detecting pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). Saturated fatty acids represent relevant DAMPs in metabolic disease, initiating TLR4 signaling that converges on NF-κB and MAPK activation through adaptor proteins MyD88, IRAK1, and TRAF6. This cascade induces proinflammatory cytokine production (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) that interferes with insulin signaling through serine phosphorylation of IRS proteins, establishing a molecular link between nutrient excess, inflammation, and insulin resistance.

TLR4 Signaling in Metabolic Tissues

Clinical studies demonstrate significant overexpression of TLR2 and TLR4 in PBMCs from T2DM patients compared to healthy controls (p < 0.001) [25]. Strong positive correlations exist between TLR4 and its adaptor proteins in controls: MyD88 (r = 0.79), IRAK1 (r = 0.83), and TRAF6 (r = 0.87) [25]. These correlations persist in T2DM patients, though moderately attenuated: MyD88 (r = 0.5), IRAK1 (r = 0.4), and TRAF6 (r = 0.8) [25]. In the hypothalamus, the resistin/TLR4/miR-155-5p axis drives neuroinflammation through NF-κB, JNK, and p38 MAPK signaling, with HFD consumption increasing hypothalamic resistin expression and subsequent microglial activation [24].

Experimental Assessment Methodologies

Gene Expression in Human PBMCs: Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) offer an accessible tissue for evaluating TLR4 pathway activity in clinical studies [25]. After overnight fasting, blood collection in EDTA-containing tubes is followed by PBMC isolation via density gradient centrifugation. RNA extraction and qRT-PCR analysis measure expression levels of TLR2, TLR4, and adaptor proteins (MyD88, IRAK1, TRAF6), with normalization to appropriate housekeeping genes. Correlation analyses between receptor and adaptor expression levels provide insights into pathway coordination in health and disease states.

Hypothalamic Neuroinflammation Models: Investigation of central TLR4 signaling requires specialized approaches [24]. Intracerebroventricular (ICV) cannulation enables direct administration of resistin or TLR4 agonists/antagonists. Hypothalamic tissue collection followed by qPCR for inflammatory markers (IL-1β, TNF-α, NF-κB, TLR4) and microglial activation markers (IBA1, CD68). Immunofluorescence staining for IBA1 in mediobasal hypothalamus assesses microglial activation status through morphological changes and staining intensity. Microglial cell lines (e.g., SIM-A9) facilitate in vitro mechanistic studies of miR-155-5p regulation and target identification.

Cross-Pathway Integration and Therapeutic Implications

Signaling Network Interdependencies

The PI3K-Akt, MAPK, and TLR4 pathways do not function in isolation but exhibit extensive cross-talk that creates a coordinated signaling network. TLR4 activation inhibits PI3K-Akt signaling through inflammatory kinase-mediated serine phosphorylation of IRS proteins, while PI3K-Akt can negatively regulate TLR4 signaling through mTOR-dependent mechanisms. MAPK pathways serve as integration points, with ERK potentially enhancing insulin signaling under certain conditions while JNK and p38 typically oppose it. This network-level understanding explains why targeted therapeutic interventions often produce pleiotropic metabolic effects.

Biomarker and Therapeutic Applications

Metabolomic approaches identify pathway-associated biomarkers with diagnostic and prognostic utility. In DKD, D-xylose emerges as a potential biomarker for metformin response, linked to MAPK pathway modulation [23]. Lysophosphatidylcholines (LPCs 14:0, 20:4) and the dipeptide Gly-His show altered plasma levels in elderly T2DM patients, reflecting underlying perturbations in lipid metabolism and inflammation [26]. Mitochondria-related genes SLC2A2, ENTPD3, ARG2, CHL1, and RASGRP1 identified through machine learning approaches predict T2DM with AUC >0.8 and correlate with immune cell infiltration patterns [27].

Established therapeutics like metformin demonstrate multi-pathway influence, modulating MAPK signaling [23] and cellular redox state in skeletal muscle [28]. Traditional Chinese medicine polyphenols target multiple pathways simultaneously, regulating gut microbiota homeostasis and affecting AMPK, PPAR, MAPK, PI3K/Akt and NF-κB pathways [8]. This multi-target approach may explain their efficacy against MetS complex pathophysiology.

Research Toolkit: Essential Methodologies and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for Pathway Analysis

| Category | Specific Reagents/Methods | Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression | TRIzol RNA extraction, DNase I treatment, qRT-PCR with SYBR Green | Quantifying pathway components in tissues | Follow MIQE guidelines; use appropriate reference genes |

| Protein Analysis | Phospho-specific antibodies (Akt, ERK, JNK, p38), Western blot | Assessing pathway activation states | Validate antibody specificity; include total protein controls |

| Metabolomics | UPLC-MS, targeted carbohydrate metabolomics | Identifying metabolic biomarkers | Use quality control pools; randomize injection order |

| Cell Culture Models | SIM-A9 microglial cells, palmitate treatment | Studying lipotoxicity and inflammation | Use appropriate FFA:BSA ratios; control for osmolarity |

| Animal Models | db/db mice, HFD-fed mice, ICV cannulation | In vivo pathway manipulation | Monitor metabolic phenotypes; control for sex differences |

| Pathway Analysis | Network pharmacology, KEGG enrichment, phosphoproteomics | Systems-level pathway mapping | Integrate multi-omics datasets; use appropriate FDR correction |

The PI3K-Akt, MAPK, and TLR4 signaling pathways represent interconnected regulatory networks whose dysregulation propagates metabolic dysfunction in MetS and T2DM. Comprehensive investigation of these pathways requires integrated methodological approaches spanning molecular techniques, omics technologies, and physiological validation. The continuing identification of pathway-associated biomarkers and therapeutic targets holds promise for advancing personalized management of metabolic diseases, with multi-target interventions potentially offering advantages for addressing the complex pathophysiology of these conditions.

Biomarker Discovery and Analytical Techniques in Clinical Practice

In the landscape of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes (T2D) research, established clinical biomarkers provide critical windows into pathophysiological processes, enabling early detection, risk stratification, and therapeutic monitoring. HbA1c, HOMA-IR, and lipid profiles represent cornerstone biochemical measurements that collectively offer insights into glycemic control, insulin sensitivity, and atherogenic dyslipidemia—the fundamental triad of metabolic dysregulation. Within drug development, these biomarkers serve essential roles across the spectrum from diagnostic and prognostic tools to pharmacodynamic response indicators and surrogate endpoints [29]. The rigorous validation of these biomarkers according to their specific context of use (COU) makes them indispensable for clinical trial design and regulatory evaluation of novel therapies targeting metabolic disorders [29].

This technical guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive resource on the analytical methodologies, clinical applications, and emerging innovations surrounding these established biomarkers, with particular emphasis on their integration in contemporary research frameworks and their utility in predicting hard clinical endpoints.

HbA1c: The Cornerstone of Glycemic Control Assessment

Analytical Methodology and Physiological Basis

Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) reflects average blood glucose levels over the preceding 2-3 months, corresponding to the red blood cell lifespan. It forms through non-enzymatic glycation of the hemoglobin beta-chain valine residue, with the rate of formation directly proportional to ambient glucose concentrations [30]. The 2025 DMSO study highlights its established role as both a diagnostic biomarker for diabetes and a monitoring biomarker for long-term glycemic control [30] [29].

Table 1: HbA1c Interpretation Standards in Clinical Practice and Research

| Category | HbA1c Range | Clinical Significance | Clinical Trial Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | <5.7% | Normal glucose homeostasis | Reference group for comparative studies |

| Prediabetes | 5.7% - 6.4% | Increased diabetes risk | Target population for prevention trials |

| Diabetes | ≥6.5% | Diabetes diagnosis | Inclusion criterion for efficacy trials |

| Treatment Target | <7.0% | Standard glycemic goal | Primary/secondary endpoint in intervention studies |

Research Applications and Correlation with Systemic Manifestations

In drug development, HbA1c serves as a primary efficacy endpoint for glucose-lowering therapies and is recognized by regulatory agencies as a validated surrogate endpoint for diabetes-related complications [29]. Recent research has expanded its contextual utility through correlations with multisystem physiological changes quantifiable via advanced imaging.

A 2024 Scientific Reports study demonstrated that HbA1c levels show significant, progressive correlations with CT-based body composition biomarkers, even in prediabetic ranges [31]. These correlations reveal the multisystem nature of metabolic syndrome and provide quantitative imaging biomarkers that may complement HbA1c in clinical trials:

- Visceral Adipose Tissue (VAT): 53% increase between normal (HbA1c <5.7%) and poorly-controlled diabetes (HbA1c >7.0%) in female cohort

- Organ Volumes: 22% increase in kidney volume and 24% increase in liver volume across the same HbA1c spectrum

- Tissue Density Changes: 6% decrease in liver density (indicating hepatic steatosis) and 21% decrease in skeletal muscle density (indicating myosteatosis)

These objective CT biomarkers demonstrate that metabolic syndrome manifestations begin in the prediabetic phase and can be quantitatively tracked alongside HbA1c in longitudinal intervention studies [31].

Standardized Management and Predictive Modeling

The clinical utility of HbA1c is enhanced through structured management programs. A 2025 study evaluating China's National Metabolic Management Center (MMC) model demonstrated significant improvements in HbA1c levels following standardized management, with the absolute HbA1c level decreasing and the rate of achieving target (<7%) significantly enhanced (P<0.05) [30].

Multivariate analysis identified independent predictors for HbA1c target achievement, which were incorporated into a predictive nomogram:

- Protective Factors: Fasting blood glucose (FBG) and hematocrit (HCT)

- Risk Factor: Albumin (ALB)

The resulting predictive model exhibited favorable discriminative ability (c-index: 0.747, 95% CI: 0.703–0.790), providing a valuable tool for identifying patients who may require more intensive interventions [30].

HOMA-IR and Surrogate Indices of Insulin Resistance

Methodological Framework and Calculation

The Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) estimates insulin resistance from fasting glucose and insulin measurements using the formula: HOMA-IR = [Fasting Insulin (µU/mL) × Fasting Glucose (mmol/L)] / 22.5 [32] [33]. While the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp remains the gold standard for direct insulin sensitivity measurement, its complexity and cost limit widespread application [34] [35] [32].

Table 2: Insulin Resistance Indices: Comparative Methodologies and Performance Characteristics

| Index | Formula | Components | AUC Range | Population-Specific Cut-offs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOMA-IR | (Fasting Insulin × Fasting Glucose)/22.5 | Insulin, Glucose | 0.83-0.92 | 1.878 (Qatari population) [32] |

| TyG Index | ln[Fasting TG (mg/dL) × Fasting Glucose (mg/dL)/2] | Triglycerides, Glucose | 0.83-0.92 | 8.281 (Qatari) [32] |

| McAuley Index | exp{2.63 - 0.28ln[Insulin] - 0.31ln[TG]} | Insulin, Triglycerides | 0.83-0.92 | 7.727 (Qatari) [32] |

| TG/HDL Ratio | Triglycerides/HDL-C | Lipids only | 0.83-0.92 | 1.718 (Qatari) [32] |

| QUICKI | 1/[log(Fasting Insulin) + log(Fasting Glucose)] | Insulin, Glucose | 0.83-0.92 | 0.347 (Qatari) [32] |

Comparative Performance of IR Indices

Comprehensive validation studies enable evidence-based selection of IR indices for specific research contexts. A 2025 Frontiers in Endocrinology study compared seven surrogate IR indices in the Qatar Biobank cohort (n=7,875), reporting AUC values ranging from 0.83 to 0.92 for all indices [32]. The Triglyceride-Glucose (TyG) index emerged as the most robust measure (AUC=0.92, sensitivity=0.90, specificity=0.79), offering practical advantages in settings where insulin measurement is unavailable or cost-prohibitive [32].