Enhancing Metabolic Model Accuracy: A Guide to Advanced kcat Prediction for ecGEMs

Enzyme-constrained genome-scale metabolic models (ecGEMs) have emerged as powerful tools for predicting cellular phenotypes, optimizing metabolic engineering, and understanding proteome allocation.

Enhancing Metabolic Model Accuracy: A Guide to Advanced kcat Prediction for ecGEMs

Abstract

Enzyme-constrained genome-scale metabolic models (ecGEMs) have emerged as powerful tools for predicting cellular phenotypes, optimizing metabolic engineering, and understanding proteome allocation. However, their accuracy heavily depends on reliable enzyme turnover numbers (kcat), which are experimentally sparse and noisy. This article explores the latest computational strategies for improving kcat prediction accuracy, covering foundational principles, machine learning methodologies like DLKcat and TurNuP, troubleshooting common challenges, and rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing recent advances in deep learning, database curation, and model integration, we provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive roadmap for constructing more predictive ecGEMs, ultimately enhancing their utility in biomedical research and therapeutic development.

The Critical Role of kcat Values in Enzyme-Constrained Metabolic Modeling

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is kcat?

The enzyme turnover number, or kcat, is defined as the maximum number of chemical conversions of substrate molecules per second that a single active site of an enzyme can execute when the enzyme is fully saturated with substrate [1]. It is a direct measure of an enzyme's catalytic efficiency at saturating substrate concentrations.

How is kcat calculated from experimental data?

kcat is calculated from the limiting reaction rate (Vmax) and the total concentration of active enzyme ([E]total) using the formula:

kcat = Vmax / [E]total [2] [1].

The units of kcat are per second (s⁻¹).

What does a change in kcat tell me about my enzyme?

A mutation or modification that affects kcat suggests that the catalysis itself has been altered [3]. However, kcat reflects the rate of the slowest step along the reaction pathway after substrate binding. This step could be the chemical conversion itself, product release, or a conformational change. Therefore, an inference that an altered group directly mediates chemistry is tentative until further experiments (like pre-steady-state kinetics) are performed [3].

What is the difference between kcat and the Specificity Constant (kcat/Km)?

While kcat measures the maximum turnover rate under saturating conditions, the specificity constant (kcat/Km) is a measure of an enzyme's efficiency at low substrate concentrations [3]. It is a second-order rate constant (M⁻¹s⁻¹). The substrate with the highest kcat/Km value is considered the enzyme's best or preferred substrate. Enzymes with kcat/Km values near the diffusional limit (10⁸ to 10⁹ M⁻¹s⁻¹) are considered to have achieved "catalytic perfection," such as triose phosphate isomerase [3].

Why are predicted kcat values crucial for metabolic modeling?

In enzyme-constrained genome-scale metabolic models (ecGEMs), kcat values are used to set constraints on the maximum fluxes of metabolic reactions. Accurate kcat values are essential because they directly influence the model's predictions of cellular phenotypes, proteome allocation, and metabolic fluxes [4] [5]. Since experimentally measured kcat data are sparse and noisy, machine learning-based prediction tools have become key for obtaining genome-scale kcat datasets, thereby improving the accuracy of ecGEMs [4] [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

Issue: High Variability in Measured kcat Values

| Potential Cause | Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Differing Assay Conditions | kcat is sensitive to environmental factors such as pH, temperature, ionic strength, and cofactor availability [4]. |

Standardize all assay conditions. When comparing values from the literature, note the specific conditions under which they were measured. |

| Enzyme Purity/Activity | The calculated kcat value depends on an accurate knowledge of the concentration of active enzyme [2]. |

Use reliable methods (e.g., active site titration) to determine the concentration of functionally active enzyme, not just total protein. |

| Unaccounted For Inhibition | Product inhibition or contamination by low-level inhibitors can lead to an underestimated Vmax, and thus an underestimated kcat. |

Include steps to remove products during assays or test for product inhibition. Ensure substrates are pure. |

Issue: Interpreting the Impact of Mutations on Enzyme Activity

| Observation | Tentative Interpretation | Further Validation |

|---|---|---|

| A mutation causes a decrease in kcat | The mutation likely affects a step involved in catalysis or a subsequent step like product release [3]. | Perform pre-steady-state kinetics to pinpoint the affected step (e.g., chemistry vs. product release). |

| A mutation causes a change in Km | The mutation may have affected substrate binding, but caution is needed [3]. | Determine the substrate binding affinity (Kd) directly using methods like isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) or filter binding assays to confirm if Km ≈ Kd [3]. |

A mutation has no effect on kcat or Km |

The mutated residue is likely not critical for substrate binding or the catalytic steps reflected in kcat. |

Consider if the mutation affects other properties like stability or allosteric regulation. |

Experimental Protocol: Determining kcat Experimentally

Objective: To determine the turnover number (kcat) of a purified enzyme for its substrate.

Principle: The maximum velocity (Vmax) of the enzymatic reaction is measured under saturating substrate conditions. The kcat is then calculated by dividing Vmax by the known concentration of active enzyme sites [2].

Materials and Reagents

- Purified enzyme of known active concentration.

- Substrate solution at a concentration significantly above (e.g., 10x) its expected Km.

- Assay buffer (appropriate pH and ionic strength).

- Cofactors or coenzymes required for activity.

- Equipment to monitor the reaction in real-time (e.g., spectrophotometer, fluorometer).

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Prepare Enzyme and Substrate Solutions: Dilute the purified enzyme and substrate into the assay buffer. Keep the enzyme on ice until ready to use.

- Set Up Reaction: In a cuvette or plate well, add the appropriate volume of assay buffer, cofactors, and substrate solution. The final substrate concentration should be saturating.

- Initiate Reaction: Start the reaction by adding a small, precise volume of the enzyme solution. Mix quickly and thoroughly.

- Monitor Reaction Rate: Continuously record the signal (e.g., absorbance, fluorescence) corresponding to product formation or substrate consumption over time. The initial linear portion of the progress curve represents the initial velocity (

V₀). - Repeat: Repeat steps 2-4 using at least two other substrate concentrations that are confirmed to be saturating to ensure

Vmaxhas been reached. - Calculate Vmax: The measured initial velocity under saturating conditions is

Vmax. - Calculate kcat: Use the formula:

kcat (s⁻¹) = Vmax (M s⁻¹) / [Active Enzyme] (M)[2].

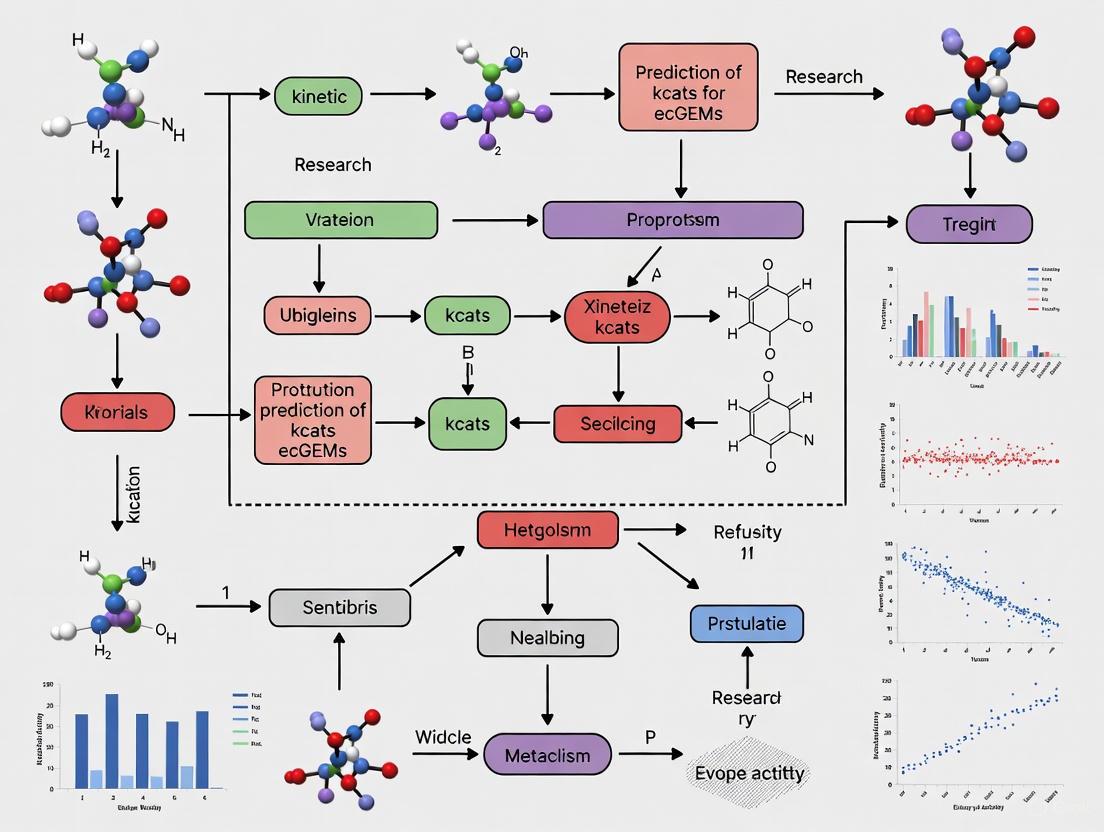

Diagram: Workflow for Experimental kcat Determination

Computational Prediction of kcat for Metabolic Models

With the vast number of enzymatic reactions in a cell, high-throughput computational methods are essential for obtaining the kcat values needed to build enzyme-constrained metabolic models (ecGEMs).

Deep Learning-Based kcat Prediction (DLKcat)

Principle: The DLKcat method uses a deep learning model that takes substrate structures and enzyme protein sequences as input to predict kcat values [4].

- Substrate Input: Substructures are represented as molecular graphs converted from SMILES strings and processed by a Graph Neural Network (GNN).

- Enzyme Input: Protein sequences are split into overlapping n-gram amino acids and processed by a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN).

- Output: The model predicts a numerical

kcatvalue [4].

Protocol: Using Predicted kcat Values for ecGEM Reconstruction

- Data Curation: Gather a comprehensive dataset of enzyme-substrate pairs with known

kcatvalues from databases like BRENDA and SABIO-RK [4]. - Model Training: Train the DLKcat model on the curated dataset. The model learns to associate features of the substrate and enzyme with the turnover number.

- Genome-Scale Prediction: Use the trained model to predict

kcatvalues for all enzyme-substrate pairs in the target organism's metabolic network [4]. - Model Integration: Incorporate the predicted

kcatvalues into a genome-scale metabolic model using pipelines like ECMpy or GECKO. This adds enzyme capacity constraints to the model [5] [6]. - Model Validation: Test the predictive performance of the resulting ecGEM by comparing its simulations of growth rates, substrate uptake, and byproduct secretion against experimental data [4] [6].

Diagram: Workflow for Constructing an ecGEM Using Predicted kcats

| Tool Name | Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| DLKcat | Deep learning-based prediction of kcat from substrate structure and protein sequence [4]. |

Used to predict genome-scale kcat profiles for 343 yeast species, enabling large-scale ecGEM reconstruction [4]. |

| TurNuP | Predicts kcat using enzyme features and differential reaction fingerprints [6]. |

Successfully applied to build an enzyme-constrained model for Myceliophthora thermophila [6]. |

| ECMpy | An automated workflow for constructing enzyme-constrained models [5] [6]. | Used to build ecGEMs for E. coli, Bacillus subtilis, and Corynebacterium glutamicum [5]. |

| GECKO | A method to enhance GEMs with enzyme constraints by incorporating enzyme kinetics and proteomics data [5]. | Used to construct ecYeast, which improved prediction of metabolic phenotypes and proteome allocation [5]. |

| Item | Function | Example/Description |

|---|---|---|

| BRENDA Database | A comprehensive enzyme information system containing functional data, including curated kcat values [4]. |

Primary source for experimental kinetic data used to train and validate prediction models [4]. |

| SABIO-RK Database | A database for biochemical reaction kinetics with curated kcat and Km values [4]. |

Another key resource for kinetic parameters, often used alongside BRENDA [4]. |

| UniProt Database | A resource for protein sequence and functional information, including annotated active sites [7]. | Provides accurate protein sequences for enzymes, which are critical input for machine learning models like DLKcat [4]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | A type of deep learning model that operates on graph structures [4]. | Used to process the molecular graph of a substrate for kcat prediction [4]. |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | A deep learning model architecture well-suited for processing structured grid data like sequences [4]. | Used to process the amino acid sequence of an enzyme for kcat prediction [4]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is kcat and why is it a critical parameter in systems biology?

kcat, or the enzyme turnover number, is the maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme molecule per second under saturating substrate conditions [8]. It defines the maximum catalytic efficiency of an enzyme and is a critical parameter for understanding cellular metabolism, proteome allocation, and physiological diversity [4]. In enzyme-constrained genome-scale metabolic models (ecGEMs), kcat values quantitatively link proteomic costs to metabolic flux, making them essential for accurately simulating growth abilities, metabolic shifts, and proteome allocations [4] [9].

2. Why is obtaining high-quality kcat data so challenging?

The primary challenges are data scarcity and experimental variability.

- Sparsity: Large collections of kcat values exist in databases like BRENDA and SABIO-RK, but they are sparse compared to the vast number of known organisms and metabolic enzymes [4]. For instance, in a S. cerevisiae ecGEM, only about 5% of all enzymatic reactions have fully matched kcat values in BRENDA [4].

- Variability: Experimentally measured kcat values can have considerable noise due to varying assay conditions, such as pH, temperature, cofactor availability, and different experimental methods [4] [9]. This variability can mask global trends in enzyme evolution and kinetics.

3. What are the standard experimental methods for determining kcat?

The standard protocol involves measuring enzyme velocity at varying substrate concentrations to determine Vmax, the maximum reaction velocity [10].

- Experiment: Conduct assays to measure initial reaction velocities (Y) across a range of substrate concentrations (X).

- Analysis: Fit the resulting data to the Michaelis-Menten equation to determine Km and Vmax.

- Calculation: Calculate kcat using the formula: kcat = Vmax / [Etotal], where [Etotal] is the total concentration of active enzyme sites. The units of Vmax and [Etotal] must match, and the resulting kcat is expressed in units of inverse time (e.g., s⁻¹) [10] [8].

4. How can computational models help overcome kcat data limitations, and what are their current constraints?

Deep learning approaches, such as DLKcat, have been developed to predict kcat values from easily accessible features like substrate structures (SMILES) and protein sequences [4]. This enables high-throughput prediction of genome-scale kcat values, facilitating ecGEM reconstruction for less-studied organisms [4]. However, a critical limitation is that these models show poor generalizability when predicting kcat for enzymes that are not highly similar to those in their training data. For enzymes with less than 60% sequence identity to the training set, predictions can be worse than simply assuming an average kcat value for all reactions [11]. Their ability to predict the effects of mutations on kcat for enzymes not included in the training data is also much weaker than initially suggested [11].

5. What constitutes a "high" or "low" kcat value?

kcat values can span over six orders of magnitude across the metabolome [9]. Generally, enzymes involved in primary central and energy metabolism have significantly higher kcat values than those involved in intermediary and secondary metabolism [4]. For example:

- High kcat: Catalase has a kcat of approximately 40,000,000 s⁻¹ [8].

- Low kcat: DNA Polymerase I has a kcat of about 15 s⁻¹, reflecting a need for high accuracy over speed [8].

Experimental Protocol: Determining kcat via Michaelis-Menten Kinetics

This protocol outlines the standard methodology for experimentally determining an enzyme's kcat value.

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a series of reactions with a fixed, known concentration of the enzyme ([Etotal]). Each reaction must contain a different concentration of substrate ([S]), ranging from values well below the expected Km to values that will saturate the enzyme [10].

- Initial Velocity Measurement: For each substrate concentration, measure the initial velocity (v0) of the reaction. This is the linear rate of product formation or substrate consumption before more than ~10% of the substrate has been converted, ensuring that [S] remains approximately constant [8].

- Data Fitting: Plot the initial velocity (Y-axis) against the substrate concentration (X-axis). Fit the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation using nonlinear regression software to determine the kinetic parameters Vmax and Km [10].

- Michaelis-Menten Equation: ( v = \frac{V{max} [S]}{Km + [S]} )

- kcat Calculation: Once Vmax is determined, calculate kcat using the formula:

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

| Item | Function in kcat Determination |

|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The catalyst of interest. Must be of high purity and known concentration ([Etotal]) to calculate kcat accurately. |

| Substrate | The molecule converted by the enzyme. Must be available in pure form for preparing a range of known concentrations. |

| Assay Buffer | Provides the optimal pH and ionic environment for enzyme activity. May contain necessary cofactors or metal ions. |

| Detection System | Allows for the quantitative measurement of product formation or substrate depletion over time (e.g., spectrophotometer, fluorometer). |

Computational Prediction: The DLKcat Workflow and Interpretation

For researchers needing to predict kcat values computationally, tools like DLKcat offer a solution. The following workflow and table summarize the process and key considerations.

DLKcat Prediction Workflow:

Model Performance and Limitations:

DLKcat uses a deep learning model that combines a Graph Neural Network (GNN) to process substrate structures and a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to process protein sequences [4]. When tested on data similar to its training set, it can achieve a strong correlation with experimental values (Pearson’s r = 0.88) and predictions are generally within one order of magnitude (test set RMSE of 1.06) [4]. However, its performance is highly dependent on sequence similarity to the training data [11].

| Scenario | Reported Performance | Key Limitation & Practical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymes with high sequence identity (>99%) to training data | Pearson's r = 0.71 on test dataset [4]. | Predictions are reliable only for enzymes very similar to those already characterized in databases. |

| Enzymes with low sequence identity (<60%) to training data | Coefficient of determination (R²) becomes negative [11]. | Predictions are worse than using a constant average kcat value for all reactions. Not recommended for novel enzyme families. |

| Prediction for mutated enzymes | For mutants in test set, fails to capture variation (R² = -0.18 for mutation effects) [11]. | The model has limited utility for predicting the kinetic consequences of novel mutations not present in its training data. |

Quantitative Data on kcat Values and Prediction

The tables below summarize the range of natural kcat values and the performance metrics of the DLKcat prediction tool for easy reference.

| kcat Value Examples in Different Contexts | |

|---|---|

| Context / Enzyme | Reported kcat Value |

| Carbonic Anhydrase | 600,000 s⁻¹ [8] |

| Catalase | 40,000,000 s⁻¹ [8] |

| DNA Polymerase I | 15 s⁻¹ [8] |

| Primary Central & Energy Metabolism | Significantly higher kcat [4] [9] |

| Intermediary & Secondary Metabolism | Significantly lower kcat [4] [9] |

| DLKcat Model Performance Metrics | |

|---|---|

| Metric | Value / Finding |

| Test Set Root Mean Square Error (r.m.s.e.) | 1.06 [4] |

| Pearson's r (Whole Dataset) | 0.88 [4] |

| Performance for enzymes with <60% sequence identity to training data | Worse than using a constant average kcat (R² < 0) [11] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a standard GEM and an enzyme-constrained GEM (ecGEM)? A standard Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) is a mathematical representation of cell metabolism that primarily considers stoichiometric constraints, defining the mass balance of metabolites in a network [12]. An enzyme-constrained GEM (ecGEM) adds an extra layer of biological reality by incorporating enzyme capacity constraints [12]. This is achieved by linking metabolic reactions to the enzymes that catalyze them and considering the cell's limited capacity to synthesize proteins, the known abundance of enzymes, and their catalytic efficiency (kcat values) [12] [13]. This makes ecGEMs fundamentally more mechanistic.

Q2: In what specific scenarios do ecGEMs provide more accurate predictions than standard GEMs? ecGEMs have demonstrated superior predictive accuracy in several key areas:

- Predicting Overflow Metabolism: They accurately simulate phenomena like the Crabtree effect in yeast, where cells produce ethanol aerobically at high growth rates, which standard GEMs fail to predict [12].

- Substrate Utilization Hierarchy: They can predict the preferred order in which microorganisms consume multiple available carbon sources, a common trait in industrial fermentation broths [13].

- Dynamic Process Simulation: When combined with dynamic Flux Balance Analysis (dFBA), ecGEMs provide more realistic simulations of batch and fed-batch fermentation processes, closely matching experimental data [12].

- Identifying Metabolic Engineering Targets: By accounting for the metabolic "cost" of producing enzymes, ecGEMs can pinpoint gene knockout or overexpression targets that are more likely to be effective in real cells, helping to bridge the "Valley of Death" between lab-scale design and industrial application [12] [13].

Q3: What are the primary methods for obtaining kcat values needed to constrain an ecGEM? There are three main approaches, with machine learning becoming increasingly prominent:

- Manual Curation from Databases: Extracting experimentally measured kcat values from specialized databases like BRENDA and SABIO-RK [13].

- Machine Learning Prediction: Using tools like TurNuP, DLKcat, or UniKP to predict kcat values directly from enzyme protein sequences and substrate structures. This is especially valuable for less-studied organisms [14] [13].

- Combined Methods: Frameworks like AutoPACMEN can automatically retrieve and integrate data from multiple sources [13].

Q4: A simulation with my ecGEM fails to find a feasible solution. What could be the cause? This is a common issue. Potential causes and actions are:

- Overly Stringent Enzyme Constraints: The protein pool capacity or individual enzyme kcat values may be constrained too tightly. Action: Verify that the kcat values and total protein pool are reasonable for your organism and condition.

- Incorrect GPR Rules: The Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) associations may be inaccurate or incomplete. Action: Manually curate and verify the GPR rules for the reactions in your pathway of interest [13].

- Missing Transport or Exchange Reactions: The model may lack the necessary reactions to import nutrients or export products. Action: Check the model's exchange reaction list.

- Infeasible Biomass Objective: The defined biomass composition may not be producible under the given constraints. Action: Review the biomass precursor requirements and their synthesis pathways.

Troubleshooting Common ecGEM Simulation Issues

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Troubleshooting Action |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation fails to produce growth | Overly restrictive enzyme capacity constraints; Inaccurate biomass composition | Relax the global enzyme capacity constraint; Validate and update biomass constituents based on experimental data [13] |

| Inaccurate prediction of substrate uptake rates | Incorrect kcat values for transport reactions or key metabolic enzymes |

Use machine learning tools (e.g., UniKP, TurNuP) to refine kcat predictions for poor-performing reactions [14] [13] |

| Failure to predict known by-product secretion (e.g., ethanol) | Model lacks regulatory logic or enzyme capacity constraints are not capturing metabolic re-routing | Ensure ecGEM framework is used; ecGEMs are specifically designed to predict such overflow metabolism without needing additional regulatory rules [12] |

| Model cannot simulate co-utilization of carbon sources | Missing or incorrect kcat values for peripheral pathways |

Manually curate GPR rules and enzyme parameters for transport systems and pathways involved in utilizing the non-preferred carbon sources [13] |

Quantitative Performance: ecGEMs vs. Standard GEMs

The table below summarizes a direct comparison between a standard GEM (Yeast8) and its enzyme-constrained version (ecYeast8) in predicting S. cerevisiae physiology.

Table 1: Model Performance Comparison in Predicting S. cerevisiae Phenotypes [12]

| Predictive Task | Standard GEM (Yeast8) | Enzyme-Constrained GEM (ecYeast8) | Experimental Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass Yield on Glucose | Constant, regardless of growth rate | Decreases after a critical dilution rate (Dcrit) | Decreases after Dcrit due to overflow metabolism |

| Onset of Crabtree Effect | Not predicted | Accurately predicts Dcrit ~ 0.27 h⁻¹ | Dcrit |

| Specific Glucose Uptake | Proportional to dilution rate | Sharp increase after Dcrit | Sharp increase after Dcrit |

| Byproduct Formation (Ethanol) | Not predicted | Accurately predicts secretion at high growth rates | Secretion observed at high growth rates |

The superior performance of ecGEMs is further demonstrated in other organisms. For example, an ecGEM for Myceliophthora thermophila (ecMTM) constructed using machine learning-predicted kcat values (TurNuP) was not only able to predict growth more accurately but also correctly simulated the hierarchical utilization of five different carbon sources derived from plant biomass [13].

Experimental Protocol: Integrating Machine Learning-Predicted kcat Values into an ecGEM

This protocol outlines the key steps for constructing an ecGEM using the ECMpy workflow, leveraging machine learning to fill gaps in enzyme kinetic data [13].

1. Model Preprocessing and Update

- Action: Begin with a high-quality, well-curated stoichiometric GEM.

- Details: Update biomass composition based on experimental measurements (e.g., RNA, DNA, protein, and lipid content). Manually correct Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) rules and consolidate redundant metabolites [13].

- Example: The iDL1450 model for M. thermophila was updated to iYW1475 before ecGEM construction [13].

2. kcat Value Collection and Curation

- Action: Gather kcat values using multiple methods.

- Details:

- Extract experimentally measured kcat values from databases like BRENDA using tools like AutoPACMEN.

- Use machine learning-based prediction tools such as DLKcat or TurNuP to generate kcat values for reactions with missing data. TurNuP has been shown to outperform other methods in some ecGEM constructions [13].

- The final kcat dataset is often a combination of curated experimental values and ML-predicted values.

3. ecGEM Construction

- Action: Use a computational framework like ECMpy to build the model.

- Details: The framework integrates the kcat values, enzyme molecular weights, and the metabolic model. It adds constraints that couple reaction fluxes to the abundance and catalytic capacity of their corresponding enzymes [13].

4. Model Validation and Refinement

- Action: Test the ecGEM's predictions against experimental data.

- Details: Key validation tasks include simulating growth under different nutrient conditions, predicting substrate uptake rates, and confirming the production of known metabolites. The model's solution space should be smaller and more physiologically relevant than the standard GEM's [13].

Diagram 1: ecGEM Construction Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps for building an enzyme-constrained model, highlighting the integration of machine learning (ML) for kcat prediction.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ecGEM Development

| Tool / Resource | Function in ecGEM Research | Relevance to kcat Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| ECMpy [13] | An automated computational workflow for constructing ecGEMs. | Integrates curated and predicted kcat values directly into the model structure. |

| TurNuP [13] | A machine learning model for predicting enzyme turnover numbers (kcat). | Provides high-quality kcat predictions; was selected for building the ecMTM model for M. thermophila due to its performance. |

| UniKP [14] | A unified framework based on pre-trained language models to predict kcat, Km, and kcat/Km from protein sequences and substrate structures. | Enables high-throughput prediction of kinetic parameters, improving accuracy over previous tools. Can assist in enzyme discovery and directed evolution. |

| AutoPACMEN [13] | A method for automatically retrieving enzyme data from kinetic databases (BRENDA, SABIO-RK). | Provides a set of experimentally derived kcat values for model construction and validation. |

| BRENDA [14] | A comprehensive enzyme database containing manually curated functional data. | Serves as a primary source of experimentally measured kinetic parameters for validation and training of ML models. |

Diagram 2: How Constraints Shape an ecGEM. This diagram illustrates the core mechanism of an ecGEM, showing how enzyme-related constraints are integrated with a standard metabolic model to improve predictions.

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What are the primary limitations of using BRENDA and SABIO-RK for constructing enzyme-constrained Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (ecGEMs)? The primary limitations are significant data sparsity, substantial experimental noise, and challenges with data harmonization. In practice, this means that for many organisms, the databases lack any kinetic data, and even for well-studied models like S. cerevisiae, kcat coverage can be as low as 5% of enzymatic reactions [4]. Furthermore, measured kcat values for the same enzyme can vary considerably due to differing assay conditions (e.g., pH, temperature, cofactor availability) [4]. Inconsistent use of gene and chemical identifiers across datasets also creates a major hurdle for automated, large-scale ecGEM reconstruction [15].

FAQ 2: How can I improve the accuracy of my ecGEM when kinetic data is missing or unreliable? Researchers are increasingly turning to machine learning (ML) models to predict kcat values and fill data gaps. These models use inputs like protein sequences and substrate structures to make high-throughput predictions [4]. For critical pathway reactions, wet-lab biologists are encouraged to formally curate and model their pathway knowledge using standard formats like SBML and BioPAX with user-friendly tools such as CellDesigner. This contributes to community resources and helps alleviate the curation bottleneck [15] [16]. When using database values, always check the original source article for experimental conditions, as manual curation has been shown to resolve thousands of data inconsistencies [7].

FAQ 3: I've found conflicting kcat values in BRENDA and SABIO-RK for the same enzyme. Which one should I use? First, consult the source publications in each database to identify differences in experimental conditions (e.g., pH, temperature, organism strain) that might explain the variation [4]. If the conditions are similar, consider using a statistically robust approach, such as taking the median value from multiple studies to mitigate the impact of outliers. For the most reliable results, prioritize values from studies that use standardized assay conditions relevant to your modeling context (e.g., physiological pH). Advanced ML models like RealKcat are now trained on manually curated datasets that resolve such inconsistencies, and their predictions can serve as a useful benchmark [7].

FAQ 4: What are the best practices for annotating molecular entities in a pathway model to ensure computational usability? Always use standardized, resolvable identifiers from authoritative databases. For genes, use NCBI Gene or Ensembl identifiers; for proteins, use UniProt; and for chemical compounds, use ChEBI or LIPID MAPS [15]. Consistent use of these identifiers is crucial for computational tools to correctly map and integrate data from different sources. Avoid using common names or synonyms alone, as they are ambiguous for computers. When using pathway editing tools like CellDesigner, leverage integrated identifier resolution features to ensure proper annotation [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: My ecGEM fails to predict known experimental growth phenotypes.

- Potential Cause 1: Inaccurate enzyme kinetic constraints. The kcat values constraining your model may be incorrect or misapplied.

- Potential Cause 2: Lack of underground metabolism or enzyme promiscuity. Standard databases and annotations may miss non-canonical enzyme activities.

- Solution: Consider enzyme promiscuity by using ML tools that can predict kcat values for alternative substrates. DLKcat, for instance, has demonstrated an ability to differentiate between native and underground metabolism [4].

Problem: I cannot find kcat values for a significant portion of reactions in my organism of interest.

- Potential Cause: The organism is non-model or poorly characterized, leading to extreme data sparsity.

- Solution:

- Use Orthology: Find a well-studied ortholog of your enzyme in a model organism (e.g., E. coli or S. cerevisiae) and use its kcat value as a proxy [15].

- Leverage Machine Learning: Employ a high-throughput kcat prediction tool. For example, DLKcat can predict kcat values from protein sequences and substrate structures for any organism, providing genome-scale coverage where experimental data is absent [4].

- Manual Curation: For a small number of critical reactions, manually curate kinetic parameters from the primary literature, ensuring to document the experimental context [7].

- Solution:

Problem: Merging pathway data from different sources leads to identifier conflicts and a broken network.

- Potential Cause: Inconsistent naming conventions and identifiers for genes, proteins, and metabolites.

- Solution: Use pathway analysis tools that support data integration and reconciliation. For instance, the PathwayAccess plugin for CellDesigner allows you to download and integrate pathways from multiple datasources [17]. Always convert all entity identifiers to a standard namespace (e.g., from HGNC for genes, ChEBI for chemicals) before merging models [15].

Database Limitations at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core limitations of traditional kinetic databases and emerging computational solutions.

Table 1: Key Limitations of Major Kinetic Databases and Computational Solutions

| Feature | BRENDA/SABIO-RK Limitations | Emerging ML Solutions (e.g., DLKcat, RealKcat) |

|---|---|---|

| Data Coverage | Sparse; e.g., only ~5% of S. cerevisiae reactions have a fully matched kcat [4]. | High-throughput; enables genome-scale kcat prediction for 1000s of enzymes [4]. |

| Data Quality & Noise | High experimental variability due to differing assay conditions [4]. | Trained on manually curated datasets (e.g., KinHub-27k), resolving 1000s of inconsistencies [7]. |

| Organism Scope | Biased towards well-studied model organisms. | Generalizable; can predict for enzymes from any organism using sequence and structure [4]. |

| Mutation Sensitivity | Limited ability to predict the kinetic effect of point mutations. | Models like RealKcat are highly sensitive to mutations, even predicting complete loss of activity from catalytic residue deletion [7]. |

| Data Integration | Identifier inconsistencies can complicate automated data merging [15]. | Uses standardized feature embeddings (e.g., ESM-2 for sequences, ChemBERTa for substrates) [7]. |

Experimental Protocol: Manual Curation of Kinetic Data from Primary Literature

This protocol is based on the rigorous methodology used to create the KinHub-27k dataset for training the RealKcat model [7].

- Source Article Collection: Identify relevant primary literature using database entries from BRENDA and SABIO-RK as starting points.

- Data Extraction: For each article, systematically extract the following data into a standardized template:

- Enzyme protein sequence (from UniProt)

- Substrate structure (as a SMILES string)

- Experimental kcat and KM values

- Exact mutation information (if applicable)

- Key experimental conditions (pH, temperature, organism)

- Cross-Referencing and Inconsistency Resolution: Corroborate every data point against the original article. Resolve any discrepancies in reported values, substrate identity, or mutation positions. The RealKcat curation process resolved over 1,800 inconsistencies from 2,158 articles [7].

- Data Consolidation: Remove duplicate entries. For unique enzyme-substrate pairs with multiple entries, retain the entry with the most physiologically relevant conditions or use statistical aggregation (e.g., median value).

- Creation of a Negative Dataset (Optional for Catalytic Awareness): To train models that recognize inactive enzymes, generate synthetic data by mutating known catalytic residues (annotated in UniProt/InterPro) to alanine and assign them a kcat of 0 [7].

Table 2: Key Resources for Kinetic Data Handling and ecGEM Reconstruction

| Resource Name | Type | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| BRENDA | Database | The most comprehensive repository of manually curated enzyme functional data, including kinetic parameters [4]. |

| SABIO-RK | Database | A curated database specializing in biochemical reaction kinetics, including systemic properties [7]. |

| UniProt | Database | Provides authoritative protein sequence and functional information, crucial for accurate enzyme annotation [15]. |

| ChEBI | Database | A curated dictionary of chemical entities of biological interest, providing standardized identifiers for metabolites [15]. |

| CellDesigner | Software | A user-friendly graphical tool for drawing and annotating pathway models in standardized formats (SBML, BioPAX) [16]. |

| DLKcat | ML Model | Predicts kcat values from substrate structures and protein sequences, enabling genome-scale kcat prediction [4]. |

| RealKcat | ML Model | A state-of-the-art model trained on rigorously curated data, offering high accuracy and sensitivity to mutations [7]. |

| BioPAX Export Plugin | Software Utility | A CellDesigner plugin that allows export of pathway models to BioPAX format, facilitating data sharing and integration [17] [16]. |

Workflow for Robust kcat Data Acquisition and Curation

The following diagram illustrates a recommended workflow for obtaining reliable kcat data, integrating both database and computational approaches to overcome individual limitations.

Machine Learning Approaches for High-Throughput kcat Prediction

FAQs: Core Concepts and Applications

Q1: What is DLKcat and what is its primary purpose in metabolic research? DLKcat is a deep learning tool designed to predict enzyme turnover numbers (kcat) by combining a Graph Neural Network (GNN) for processing substrate structures with a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for analyzing protein sequences [4]. Its primary purpose is to enable high-throughput kcat prediction for metabolic enzymes from any organism, addressing a major bottleneck in the reconstruction of enzyme-constrained Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (ecGEMs). By providing genome-scale kcat values, DLKcat allows researchers to build more accurate models that better simulate cellular metabolism, proteome allocation, and physiological diversity [4].

Q2: What are the key inputs required to run a DLKcat prediction? The model requires two primary inputs [4] [18]:

- Protein Sequence: The amino acid sequence of the enzyme.

- Substrate Structure: The substrate structure represented as a SMILES string (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System). For reactions involving multiple substrates, the SMILES strings need to be concatenated.

Q3: Can DLKcat be used to guide protein engineering? Yes. DLKcat incorporates a neural attention mechanism that helps identify which specific amino acid residues in the enzyme sequence have the strongest influence on the predicted kcat value [4] [18]. This allows researchers to pinpoint residues that are critical for enzyme activity. Experimental validations have shown that residues with high attention weights are significantly more likely to cause a decrease in kcat when mutated, providing valuable, data-driven guidance for targeted mutagenesis and directed evolution campaigns [4].

Q4: How does DLKcat perform compared to experimental data? DLKcat shows strong correlation with experimentally measured kcat values. On a comprehensive test dataset, the model achieved a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.71, with predicted and measured kcat values generally falling within one order of magnitude (root mean square error of 1.06) [4]. The model is also capable of capturing the effects of amino acid substitutions, maintaining a high correlation (Pearson's r = 0.90 for the whole dataset) for mutated enzymes [4].

Q5: What are the latest benchmarking results for DLKcat and similar tools? A 2025 independent evaluation compared several kcat prediction tools using an unbiased dataset designed to prevent over-optimistic performance estimates. The study introduced a new model, CataPro, which was benchmarked against DLKcat. The results, summarized in the table below, provide a realistic view of the current performance landscape for kcat prediction models [19].

Table 1: Benchmarking of kcat Prediction Models on an Unbiased Dataset (2025 Study)

| Model | Key Features | Reported Performance (on unbiased test sets) |

|---|---|---|

| DLKcat | Combines GNN for substrates and CNN for protein sequences [4]. | Served as a baseline; newer models showed enhanced accuracy and generalization [19]. |

| TurNuP | Uses fine-tuned ESM-1b protein embeddings and differential reaction fingerprints [19]. | Outperformed DLKcat in a specific ecGEM construction case study for Myceliophthora thermophila [20]. |

| CataPro | Utilizes ProtT5 protein language model embeddings combined with molecular fingerprints [19]. | Demonstrated superior accuracy and generalization ability compared to DLKcat and other baseline models [19]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Prediction Accuracy or Inconsistent Results

- Potential Cause: Incorrect SMILES Format. The GNN relies on accurately formatted SMILES strings to generate a valid molecular graph of the substrate.

- Solution: Validate all input SMILES strings using a chemical validator tool (e.g., using RDKit in Python) to ensure they are canonical and chemically plausible.

- Potential Cause: Data Scarcity for Specific Enzyme Families. Like all data-driven models, DLKcat's performance is dependent on the training data. Rare or novel enzyme classes may have poorer predictions.

- Potential Cause: Underlying Model Limitations. The benchmark in [19] indicates that DLKcat's relatively simple CNN-based protein encoding may not capture sequence context as effectively as modern protein language models, especially with limited data.

- Solution: For critical applications, acknowledge this limitation and consider the prediction as a strong prior rather than a definitive value. Use it to rank enzyme candidates or mutation targets rather than relying on the absolute value.

Problem 2: Handling Multi-Substrate Reactions

- Potential Cause: The model requires a single input for substrates. The standard DLKcat interface is designed for a single substrate-protein pair input [18].

- Solution: For multi-substrate reactions, concatenate the SMILES strings of all substrates into a single string before input. Be aware that the order of concatenation may subtly influence the GNN's processing, so it is advisable to maintain consistency across all predictions for a given reaction type.

Problem 3: Interpreting Results for ecGEM Integration

- Potential Cause: High variability in kcat values. Experimentally measured kcat data from databases like BRENDA can be noisy due to different assay conditions [4].

- Solution: When building ecGEMs, use DLKcat predictions to fill gaps for reactions without experimental data. It is recommended to use the predicted values for comparative analysis (e.g., ranking potential enzyme engineering targets or identifying metabolic bottlenecks) rather than as absolute kinetic constants. As shown in [20], using machine learning-predicted kcat values can lead to ecGEMs with improved predictions of growth phenotypes and proteome allocation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for DLKcat and ecGEM Research

| Resource / Reagent | Function / Application | Source / Example |

|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid Sequence | Primary input for the CNN arm of DLKcat; defines the enzyme. | UniProt [19] |

| SMILES String | Primary input for the GNN arm of DLKcat; defines the substrate's molecular structure. | PubChem [19] |

| Experimental kcat Data | For model training, validation, and benchmarking. | BRENDA, SABIO-RK [4] [19] |

| Protein Language Models (e.g., ProtT5) | Used in newer models (CataPro) to generate more informative enzyme sequence embeddings, potentially improving accuracy [19]. | Hugging Face, etc. |

| ecGEM Reconstruction Pipeline | Framework for integrating kcat values into genome-scale metabolic models. | ECMpy [20] |

Experimental Protocol: Key Workflow for ecGEM Enhancement with DLKcat

The following workflow, derived from published studies [4] [20], details the steps for using DLKcat to enhance enzyme-constrained metabolic models.

1. Input Data Preparation:

- Enzyme Sequences: Retrieve the amino acid sequences for all enzymes in the metabolic model from a reliable database such as UniProt [19].

- Substrate SMILES: For each metabolic reaction, obtain the canonical SMILES strings for all substrates from a database like PubChem [19]. For multi-substrate reactions, concatenate the SMILES strings into a single input.

2. High-Throughput kcat Prediction:

- Run the DLKcat model for all enzyme-substrate pairs. This can be automated via scripting using the available web server (e.g., Tamarind.bio) [18] or local installation.

- The model internally processes the data by:

- Protein CNN: Splitting the amino acid sequence into overlapping 3-gram sequences and processing them through convolutional layers to create a feature vector [4].

- Substrate GNN: Converting the SMILES string into a molecular graph and using a graph neural network with a radius of 2 to learn structural features [4].

- The two feature vectors are combined and passed through fully connected layers to output a predicted log10(kcat) value.

3. ecGEM Reconstruction and Parameterization:

- Map the predicted kcat values to the corresponding reactions in the draft Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM).

- Use a Bayesian pipeline or a framework like ECMpy to integrate the kcat values as enzyme capacity constraints, effectively converting the standard GEM into an enzyme-constrained GEM (ecGEM) [4] [20].

4. Model Validation and Analysis:

- Validate the resulting ecGEM by simulating growth under various conditions and comparing the predictions to experimentally observed phenotypes (e.g., growth rates, carbon source utilization) [20].

- Analyze the model to identify enzyme-limited metabolic pathways or propose new targets for metabolic engineering, leveraging the more complete kcat coverage provided by DLKcat [4] [20].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the main advantages of using Gradient-Boosted Trees (GBTs) for kcat prediction over other machine learning models?

Gradient-Boosted Trees offer several key advantages for predicting enzyme kinetic parameters like kcat. They combine multiple weak learners (decision trees) in a sequential manner where each new tree corrects the errors of the previous ones, leading to high predictive accuracy [21] [22]. Unlike single decision trees or random forests, GBTs work as a combined ensemble where individual trees may perform poorly alone but achieve strong results when aggregated [23]. Models like TurNuP have demonstrated that GBTs generalize well even to enzymes with low sequence similarity (<40% identity) to those in the training set, addressing a critical limitation of previous approaches [21].

2. How does TurNuP's implementation of gradient-boosted trees specifically improve kcat prediction accuracy?

TurNuP improves kcat prediction through its sophisticated input representation and model architecture. It represents complete chemical reactions using differential reaction fingerprints (DRFPs) that capture substrate and product transformations, and represents enzymes using modified Transformer Network features trained on protein sequences [21]. This comprehensive input representation allows the gradient-boosted tree model to learn complex patterns between enzyme-reaction pairs and their catalytic efficiencies. When parameterizing metabolic models, TurNuP-predicted kcat values lead to improved proteome allocation predictions compared to previous methods [21].

3. What are the key hyperparameters to tune when implementing gradient-boosted trees for enzyme kinetics prediction?

The most critical hyperparameters for optimizing GBT performance include learning rate, nestimators, and tree-specific constraints [23]. The learning rate controls how much each new tree contributes to the ensemble, with lower values (e.g., 0.01) requiring more trees but potentially achieving better generalization, while higher values (e.g., 0.5) learn faster but may overfit [23]. The nestimators parameter determines the number of sequential trees, with insufficient trees leading to underfitting and too many increasing computation time without substantial gains. Additionally, constraints like maxdepth, minsamplesleaf, and maxleaf_nodes help control model complexity and prevent overfitting [23].

4. How do ensemble methods like bagging and boosting differ in their approach to improving kcat prediction models?

Bagging and boosting represent two distinct ensemble strategies with different mechanisms and applications. Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating) trains multiple models in parallel on random subsets of the data and aggregates their predictions, primarily reducing variance and combating overfitting [22]. Random Forest is a well-known bagging extension. Boosting, including gradient-boosted trees, trains models sequentially where each new model focuses on correcting errors of the previous ensemble, primarily reducing bias and improving overall accuracy [22]. While bagging models are independent and can be parallelized, boosting models build sequentially on previous results, making them particularly effective for complex prediction tasks like kcat estimation where capturing nuanced patterns is essential [21] [22].

5. What are the common failure modes when applying ensemble methods to kcat prediction, and how can they be addressed?

Common issues include overfitting on limited enzyme kinetics data, poor generalization to novel enzyme classes, and feature representation limitations. Overfitting can be addressed through proper regularization of ensemble models via hyperparameter tuning (learning rate, tree depth, subsampling) and using cross-validation techniques that ensure no enzyme sequences appear in both training and test sets [21]. Poor generalization to new enzyme families can be mitigated by using protein language model embeddings (like ESM-1b) that capture evolutionary information, as demonstrated in TurNuP [21]. Additionally, ensuring comprehensive reaction representation through differential reaction fingerprints rather than simplified substrate representations helps maintain accuracy across diverse enzymatic reactions [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Generalization to Enzymes Not in Training Distribution

Symptoms:

- Accurate predictions for enzymes similar to training set but poor performance on novel enzymes

- High error rates for enzymes with <40% sequence identity to training examples

- Inconsistent performance across different enzyme classes

Solutions:

- Implement Advanced Protein Representations: Replace simple sequence encoding with pretrained protein language model features like ESM-1b or ProtT5, which capture evolutionary information and structural constraints [21] [24].

- Utilize Comprehensive Reaction Fingerprints: Employ differential reaction fingerprints (DRFPs) that encode complete reaction transformations rather than single substrate properties [21].

- Strategic Data Splitting: Ensure training and test sets contain distinct enzyme sequences to properly evaluate generalization capability [21].

- Transfer Learning: Initialize models with parameters trained on larger protein sequence datasets before fine-tuning on kinetic data [24].

Issue 2: Hyperparameter Optimization Challenges

Symptoms:

- Model converges slowly or requires excessive computation time

- Underfitting or overfitting despite seemingly appropriate architecture

- Inconsistent performance across different random seeds or data splits

Solutions:

- Systematic Hyperparameter Search: Implement random grid search or Bayesian optimization focusing on key parameters [23]: learning_rate: Test values between 0.01-0.5 n_estimators: Evaluate between 100-1000 trees max_depth: Explore 3-15 levels min_samples_leaf: Try 1-20 samples

- Learning Rate and Estimator Balancing: Use lower learning rates (0.01-0.1) with higher n_estimators for better generalization [23].

- Early Stopping: Implement stopping criteria when validation performance plateaus to prevent overfitting and reduce training time [23].

- Cross-Validation Strategy: Use fivefold cross-validation with care to ensure no data leakage between folds [21].

Issue 3: Handling Noisy and Sparse Enzyme Kinetics Data

Symptoms:

- High variance in predictions for similar enzyme-reaction pairs

- Model performance sensitive to data preprocessing choices

- Difficulty learning consistent patterns from experimental measurements

Solutions:

- Comprehensive Data Curation: Implement rigorous preprocessing including removal of unrealistic kcat values (<10⁻²·⁵/s or >10⁵/s), geometric mean calculation for replicate measurements, and exclusion of non-wild-type enzymes and non-natural reactions [21].

- Uncertainty Quantification: Incorporate probabilistic approaches that provide confidence intervals alongside predictions, as demonstrated in CatPred [24].

- Data Augmentation: Generate synthetic training examples for under-represented enzyme classes through catalytic residue mutations or sequence variations [7].

- Ensemble Diversity: Combine multiple ensemble methods or feature representations to leverage complementary strengths and improve robustness [25].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing TurNuP-Style Gradient-Boosted Trees for kcat Prediction

Objective: Reproduce and extend TurNuP methodology for predicting enzyme turnover numbers using gradient-boosted trees with comprehensive feature engineering.

Materials and Reagents:

- Enzyme Kinetics Data: Curated from BRENDA, SABIO-RK, and UniProt databases [21]

- Protein Language Model: ESM-1b or ProtT5 for enzyme sequence embeddings [21] [24]

- Chemical Informatics Tools: RDKit for reaction fingerprint calculation [21]

- Machine Learning Framework: XGBoost, LightGBM, or scikit-learn GradientBoostingRegressor [23]

- Computational Resources: Multi-core CPU or GPU acceleration for transformer inference

Methodology:

- Data Collection and Preprocessing

- Compile kcat measurements from databases with associated enzyme sequences and reaction equations

- Filter to include only wild-type enzymes and natural reactions

- Remove outliers with kcat <10⁻²·⁵/s or >10⁵/s [21]

- Calculate geometric mean for multiple measurements of same enzyme-reaction pair

- Split data ensuring no enzyme sequences overlap between training and test sets

Feature Engineering

- Enzyme Representation: Generate embeddings using pretrained protein language model

- Reaction Representation: Calculate differential reaction fingerprints (DRFPs) encoding complete reaction transformation

- Feature Integration: Concatenate enzyme and reaction features into unified input representation

Model Training and Validation

- Implement gradient-boosted tree regressor with log10-transformed kcat values

- Perform fivefold cross-validation with random grid search for hyperparameter optimization

- Evaluate performance using coefficient of determination (R²) and mean squared error

- Test generalization on enzymes with varying sequence similarity to training set

Model Interpretation and Application

- Analyze feature importance to identify determinants of catalytic efficiency

- Integrate predicted kcat values into enzyme-constrained metabolic models

- Validate through comparison with experimental proteome allocation data

Protocol 2: Comparative Analysis of Ensemble Methods for Kinetic Parameter Prediction

Objective: Systematically evaluate and compare different ensemble methodologies for predicting enzyme kinetic parameters.

Materials and Reagents:

- Benchmark Datasets: Curated kcat, Km, and Ki measurements from multiple sources [24]

- Feature Extraction Tools: ESM-2 for sequence embeddings, ChemBERTa for substrate representations [7]

- Ensemble Implementations: Scikit-learn Bagging and Boosting classifiers, XGBoost, CatBoost [22]

- Evaluation Metrics: Order-of-magnitude accuracy, R², mean squared error [7]

Methodology:

- Dataset Preparation

- Curate comprehensive dataset with 27,176 experimentally verified enzyme kinetics entries [7]

- Resolve inconsistencies through manual verification of original sources

- Generate negative examples by mutating catalytic residues to alanine

- Cluster kinetic values by orders of magnitude for classification-based approaches

Ensemble Method Implementation

- Bagging Approach: Implement Random Forest with varying tree counts and feature subsets

- Boosting Approach: Configure Gradient-Boosted Trees with optimized learning schedules

- Stacking Approach: Develop heterogeneous ensembles with meta-learners

- Comparative Baselines: Include single tree models and deep learning approaches

Performance Evaluation

- Assess prediction accuracy within one order of magnitude of experimental values

- Evaluate sensitivity to mutations in catalytically essential residues

- Test generalization to enzyme classes underrepresented in training data

- Measure computational efficiency and scaling properties

Biological Validation

- Incorporate predictions into kinetic models of metabolism

- Compare predicted versus experimental growth rates and metabolic fluxes

- Validate capability to detect complete loss of activity upon catalytic residue mutation

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for Ensemble-Based kcat Prediction

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Research | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-1b/ESM-2 | Protein Language Model | Generates evolutionary-aware enzyme sequence embeddings | TurNuP enzyme representation [21] |

| Differential Reaction Fingerprints (DRFP) | Chemical Representation | Encodes complete reaction transformation information | TurNuP reaction representation [21] |

| XGBoost/LightGBM | Gradient-Boosted Tree Implementation | Ensemble learning algorithm for kcat regression | TurNuP core model architecture [21] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Toolkit | Calculates molecular fingerprints and reaction representations | Reaction fingerprint generation [21] |

| BRENDA/SABIO-RK | Kinetic Database | Source of experimental kcat measurements for training | Data curation for TurNuP, CatPred [21] [24] |

| SMOTE | Data Augmentation | Balances class representation in classification approaches | RealKcat dataset preparation [7] |

| ProtT5 | Protein Language Model | Alternative enzyme sequence representation | UniKP feature engineering [24] |

| ChemBERTa | Chemical Language Model | Substrate structure representation | RealKcat substrate embedding [7] |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Ensemble Methods for kcat Prediction

| Model | Ensemble Type | Key Features | Reported Performance | Generalization Capability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TurNuP | Gradient-Boosted Trees | DRFP reaction fingerprints + Protein LM embeddings | Outperforms previous models [21] | Good generalization to enzymes with <40% sequence identity to training set [21] |

| ECEP | Weighted Ensemble CNN + XGBoost | Multi-feature ensemble with weighted averaging | MSE: 0.46, R²: 0.54 [25] | Improved over TurNuP and DLKcat [25] |

| CatPred | Deep Ensemble | pLM features + uncertainty quantification | 79.4% predictions within one order of magnitude [24] | Enhanced performance on out-of-distribution samples [24] |

| RealKcat | Optimized GBT | ESM-2 + ChemBERTa embeddings, order-of-magnitude clustering | >85% test accuracy [7] | High sensitivity to mutation-induced variability [7] |

| UniKP | Tree Ensemble | pLM features for enzymes and substrates | Improved in-distribution performance [24] | Limited out-of-distribution evaluation [24] |

Workflow Visualization

Enzyme-constrained genome-scale metabolic models (ecGEMs) are pivotal for simulating cellular metabolism, proteome allocation, and physiological diversity. A critical parameter for these models is the enzyme turnover number (kcat), which defines the maximum catalytic rate of an enzyme. The accurate prediction of kcat values is essential for reliable ecGEM simulations, yet experimentally measured kcat data are sparse and noisy. Structure-aware prediction represents a transformative approach by incorporating 3D protein structural data, moving beyond traditional sequence-based methods to significantly enhance the accuracy of kcat predictions and, consequently, the predictive power of ecGEMs [4].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of using 3D structural data over sequence-based models for kcat prediction?

Sequence-based models rely solely on the linear amino acid code, which often fails to capture the intricate spatial arrangements that determine enzyme function and substrate specificity. In contrast, structure-aware models explicitly incorporate 3D structural information—such as the spatial coordinates of residues in the active site, pairwise residue distances, and dihedral angles—which are directly relevant to the enzyme's catalytic mechanism. This allows the model to learn features related to substrate binding, transition state stabilization, and product release, leading to a more physiologically accurate prediction of kcat [4] [26].

Q2: I have a novel enzyme with no known experimental structure. How can I obtain a reliable 3D structure for kcat prediction?

For novel enzymes, you can use highly accurate protein structure prediction tools. We recommend:

- AlphaFold2/AlphaFold3: These AI-driven tools from Google DeepMind can predict protein structures with remarkable accuracy from amino acid sequences [27] [28].

- ColabFold: An efficient and accessible implementation of AlphaFold2 that is often used for high-throughput predictions and can be integrated into computational pipelines like tAMPer [27].

- ESMFold: A tool that uses a protein language model to predict structures directly from single sequences, without the need for multiple sequence alignments [27]. The structures predicted by these tools have been successfully used as inputs for structure-aware prediction models [27].

Q3: My structure-aware model performs poorly on a specific enzyme class. What strategies can I use to improve its accuracy? This is a common challenge, often due to limited training data for that specific class. We recommend the following strategies:

- Transfer Learning: Leverage a model pre-trained on a large, general dataset of protein structures and

kcatvalues (the source model). You can then fine-tune this model on your smaller, specific dataset (the target data). This approach has been shown to outperform models trained from scratch in approximately 90% of cases for materials property prediction, a conceptually similar problem [29]. - Data Augmentation: If your dataset is small, consider generating synthetic data points by creating slight variations of existing structures or by leveraging the attention mechanisms in models like DLKcat to identify and focus on key residues that dominate enzyme activity [4].

Q4: How can I interpret which structural features my model is using to make its kcat predictions?

To interpret your model, use an attention mechanism. This technique back-traces important signals from the model's output to its input, assigning a quantitative weight to each amino acid residue indicating its importance for the final prediction. For instance, in the DLKcat model, this method successfully identified that residues which, when mutated, led to a significant decrease in kcat, had significantly higher attention weights, validating the model's biological relevance [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Predictive Accuracy on Hold-Out Test Set

Problem: Your structure-aware model shows high performance on training data but poor performance on the validation or test data. Solution:

- Check for Data Leakage: Ensure that there is no overlap between the training and test datasets. This is especially important when working with protein families; sequences or structures from the same family should not be split across training and test sets.

- Validate Input Structures: Assess the quality of the predicted 3D structures. Use metrics like pLDDT from AlphaFold2 to identify low-confidence regions that might be introducing noise [27].

- Regularize Your Model: Apply techniques like Dropout or L2 regularization to prevent overfitting to the training data. If using a Graph Neural Network (GNN), ensure the graph construction (e.g., distance cut-off for edges) is appropriate for the task [27] [26].

Issue: Handling of Enzyme Promiscuity and Underground Metabolism

Problem: Your model fails to differentiate between an enzyme's native substrate and its promiscuous or "underground" substrates. Solution:

- Ensure your training dataset is explicitly curated to include examples of promiscuous enzyme-substrate pairs. The DLKcat model, for example, was trained on a dataset from BRENDA and SABIO-RK and successfully learned to assign higher predicted

kcatvalues to preferred substrates compared to alternative or random substrates [4]. Your model architecture should be capable of jointly learning from both the protein structure and the substrate structure (e.g., represented as a molecular graph) to capture this nuanced interaction [4].

Issue: Integrating PredictedkcatValues into ecGEMs

Problem: Successfully predicted kcat values do not lead to improved phenotype simulations in your ecGEM.

Solution:

- Sanity Check the Values: Compare the distribution of your predicted

kcatvalues to known biological ranges. For instance, DLKcat confirmed that enzymes in central metabolism were correctly assigned higherkcatvalues than those in secondary metabolism [4]. - Use a Robust Parameterization Pipeline: Implement a Bayesian pipeline, as described in the DLKcat work, to integrate the predicted

kcatvalues into the ecGEM. This approach accounts for the uncertainty in predictions and has been shown to produce models that outperform those built with previous pipelines in predicting growth phenotypes and proteome allocation [4].

The following tables summarize key performance metrics from recent studies on structure-aware prediction models relevant to kcat and ecGEMs.

Table 1: Performance of Structure-Aware Models in Bioinformatics Tasks

| Model Name | Application | Key Metric | Performance | Comparison vs. Previous Best |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tAMPer [27] | Peptide Toxicity Prediction | F1-Score | 68.7% on AMP hemolysis data | Outperforms second-best method by 23.4% |

| DLKcat [4] | kcat Prediction |

Pearson's r (Test Set) | 0.71 | N/A (Novel deep learning approach) |

| STEPS [26] | Protein Classification | Accuracy (Membrane/Non-Membrane) | Improved performance over sequence-only models | Verifies effectiveness of structure-awareness |

Table 2: Analysis of Enzyme Promiscuity by DLKcat [4]

| Substrate Category | Median Predicted kcat (s⁻¹) |

Statistical Significance (P-value) |

|---|---|---|

| Preferred Substrates | 11.07 | Baseline |

| Alternative Substrates | 6.01 | P = 1.3 × 10⁻¹² |

| Random Substrates | 3.51 | P = 9.3 × 10⁻⁶ |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Implementing a DLKcat-like Workflow forkcatPrediction

This protocol outlines the key steps for predicting kcat values using a structure-aware deep learning model.

I. Data Curation

- Source Your Data: Compile a dataset of enzyme-substrate pairs with known

kcatvalues from public databases like BRENDA and SABIO-RK [4]. - Clean the Data: Filter out entries with missing substrate, protein sequence, or

kcatinformation. Remove redundant entries to ensure a set of unique data points [4]. - Represent Substrates: Convert substrate information into a machine-readable format. Use the Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) and then represent them as molecular graphs for input into a Graph Neural Network (GNN) [4].

- Represent Proteins:

II. Model Training & Interpretation

- Architecture Selection: Employ a multi-modal deep learning architecture. The DLKcat model, for instance, combines a GNN for processing substrate graphs with a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for processing protein sequences split into n-gram amino acids [4]. An alternative is to use a GNN for the protein structure graph.

- Training: Split your data into training (80%), validation (10%), and test (10%) sets. Train the model to minimize the error between predicted and experimental

kcatvalues (e.g., using Root Mean Square Error) [4]. - Interpretation: Use an attention mechanism to identify amino acid residues in the protein sequence or structure that have a strong influence on the predicted

kcatvalue, providing biological insight [4].

III. Integration with ecGEMs

- Genome-Scale Prediction: Use the trained model to predict

kcatvalues for all enzymatic reactions in the target organism's genome [4]. - Model Parameterization: Feed the predicted

kcatvalues into a Bayesian pipeline to parameterize and constrain the ecGEM, enabling accurate simulations of phenotypes and proteome allocation [4].

Workflow Visualization: Structure-AwarekcatPrediction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Structure-Aware kcat Prediction

| Tool Name | Type | Function in Workflow | Key Feature for ecGEMs |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2/3 [28] | Structure Prediction | Generates highly accurate 3D protein structures from amino acid sequences. | Enables structural analysis for novel enzymes in less-studied organisms. |

| ColabFold [27] | Structure Prediction | Accessible, high-throughput implementation of AlphaFold2. | Facilitates rapid generation of protein structure graphs for model input. |

| DLKcat [4] | Deep Learning Model | Predicts kcat from substrate structures and protein sequences/structures. |

Provides genome-scale kcat profiles for ecGEM reconstruction. |

| tAMPer [27] | Deep Learning Model | Predicts peptide toxicity using multi-modal (sequence + structure) data. | Exemplifies the power of GNNs for structure-aware property prediction. |

| STEPS [26] | Self-Supervised Framework | Learns protein representations from structural data (distances & angles). | Can be fine-tuned for specific prediction tasks like enzyme function. |

| BRENDA/SABIO-RK [4] | Database | Source of experimental kcat data for model training and validation. |

Provides the ground truth essential for supervised learning. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary differences between the GECKO and ECMpy toolboxes? While both toolboxes are used to build enzyme-constrained metabolic models (ecGEMs), the provided search results detail GECKO's methodology and features. GECKO is an open-source toolbox, primarily in MATLAB, that enhances existing GEMs by incorporating enzyme constraints using kinetic and proteomic data [30] [31] [32]. It provides a systematic framework for reconstructing ecModels, from manual parameterization to automated pipelines for model updating [32].

Q2: My model predictions are inaccurate after adding enzyme constraints. How can I improve kcat coverage and quality? Inaccurate kcat values are a common challenge. GECKO implements a hierarchical procedure for kcat retrieval, but for less-studied organisms, coverage can be low [32]. To improve your model:

- Utilize Deep Learning Predictions: Integrate tools like DLKcat, a deep learning approach that predicts kcat values from substrate structures and protein sequences. This can provide high-throughput kcat predictions for organisms with sparse experimental data [4].

- Leverage the BRENDA Database: GECKO can automatically retrieve kinetic parameters from BRENDA. Be aware that kinetic parameters can span several orders of magnitude, even for similar enzymes [32].

- Apply Manual Curation: For key metabolic reactions, manually curate kcat values from the literature to ensure critical pathway fluxes are accurately constrained [32].

Q3: How do I integrate proteomics data into my ecGEM using GECKO? GECKO allows you to constrain enzyme usage reactions with measured protein levels [30] [31]. The general workflow is:

- Format your proteomics data, ensuring protein identifiers match those in your model.

- Use the

constrainEnzConcsfunction to apply these measurements as upper bounds for the corresponding enzyme usage reactions [30]. - The model will then draw enzyme usage from a shared pool for unmeasured proteins while respecting the individual constraints for measured enzymes [30].

Q4: What should I do if my ecModel fails to simulate or grows poorly after integration? This often indicates overly stringent constraints. Follow this troubleshooting checklist:

- Verify kcat Values: Check for implausibly low kcat values that may be bottlenecking essential reactions. Consult the BRENDA database or use DLKcat predictions for validation [4] [32].

- Inspect the Protein Pool: Ensure the total protein pool constraint (f_P) is set to a physiologically realistic value for your organism and condition.

- Check Reaction Bounds: Confirm that the uptake rates for carbon and other essential nutrients are set correctly.

- Validate Proteomics Integration: If using proteomics data, ensure that the constraints do not make the model infeasible. Temporarily relax proteomic constraints to isolate the issue [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Handling Missing kcat Values During ecModel Reconstruction

Problem: The ecModel reconstruction pipeline fails or has poor kcat coverage for non-model organisms.

Solution: Adopt a multi-tiered approach to fill kcat gaps, as outlined in the table below.

Table: Strategies for Sourcing kcat Values

| Strategy | Description | Advantage | Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organism-Specific from BRENDA | Uses kcat values measured from the target organism. | Highest quality, most physiologically relevant. | Often very sparse for non-model organisms [32]. |

| Deep Learning Prediction (DLKcat) | Predicts kcat from protein sequence and substrate structure [4]. | High-throughput; applicable to any sequenced organism. | Predictions are within one order of magnitude of measured values [4]. |

| Cross-Organism from BRENDA | Uses kcat values from a well-studied organism (e.g., E. coli or S. cerevisiae). | Better than no data. | Kinetic parameters can vary significantly between organisms [32]. |

| Manual Curation | Manually assign values based on literature for key pathway enzymes. | Improves accuracy for critical reactions. | Time-consuming and requires expertise. |

Workflow: The following diagram illustrates a recommended workflow for building a high-quality kcat dataset.

Issue 2: Resolving Numerical Instabilities and Infeasible Simulations

Problem: The ecModel returns infeasible solutions or errors during Flux Balance Analysis (FBA).

Solution: Systematically loosen constraints to identify the source of infeasibility.

Table: Common Causes and Fixes for Infeasible ecModels

| Symptom | Likely Cause | Diagnostic Step | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infeasible solution | Total protein pool is too small. | Check the f_P (protein mass fraction) value. |

Increase the f_P constraint to a physiologically reasonable higher value. |

| No growth on rich medium | An essential enzyme is over-constrained. | Check proteomics constraints or kcat values for biomass reactions. | Relax constraints on enzymes in essential pathways; verify kcat values are not too low. |

| Unexpected zero flux | A single low kcat or enzyme bound is creating a bottleneck. | Perform flux variability analysis (FVA). | Identify the bottleneck reaction and verify its associated kcat and enzyme abundance. |

| Numerical errors in solvers | The model contains very large or very small coefficients. | - | Scale kcat values (e.g., use per hour instead of per second) to improve numerical conditioning. |

Diagnostic Workflow: Follow this logical troubleshooting tree to pinpoint the issue.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Tools and Data for ecGEM Reconstruction

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in ecGEM Reconstruction |

|---|---|---|

| GECKO Toolbox | Software Toolbox | Main platform for enhancing a GEM with enzyme constraints; automates model reconstruction and simulation [30] [32]. |