Enzyme-Constrained Genome-Scale Metabolic Models: A Guide to Enhanced Predictions in Biomedical Research

Enzyme-constrained genome-scale metabolic models (ecGEMs) represent a significant advancement over traditional stoichiometric models by integrating enzyme kinetics and proteomics data to enhance the prediction of cellular phenotypes.

Enzyme-Constrained Genome-Scale Metabolic Models: A Guide to Enhanced Predictions in Biomedical Research

Abstract

Enzyme-constrained genome-scale metabolic models (ecGEMs) represent a significant advancement over traditional stoichiometric models by integrating enzyme kinetics and proteomics data to enhance the prediction of cellular phenotypes. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of ecGEMs, key methodologies like the GECKO toolbox and novel deep learning approaches for parameter estimation, strategies for model optimization and troubleshooting, and rigorous validation techniques using experimental data. By synthesizing the latest research, including applications from Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae to pathogens like Treponema pallidum and industrial workhorses like Aspergillus niger, this resource demonstrates how ecGEMs offer more accurate insights into metabolic engineering, drug target identification, and understanding of human diseases.

The Principles and Evolution of Enzyme-Constrained Metabolic Modeling

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are powerful computational tools that simulate cellular metabolism by representing the complete set of metabolic reactions within an organism. However, traditional GEMs consider only stoichiometric constraints, leading to predictions where growth and product yields increase monotonically with substrate uptake rates, a pattern that often deviates from experimental observations [1]. This limitation stems from the failure to account for critical biological realities, particularly the finite capacity of enzymatic machinery and associated proteomic costs.

Enzyme-constrained GEMs (ecGEMs) represent a transformative advancement in metabolic modeling by incorporating enzyme kinetic parameters and proteomic limitations into constraint-based frameworks. These models introduce fundamental physical and biochemical constraints, including enzyme catalytic efficiency (kcat values), enzyme molecular weights, and cellular space limitations, thereby creating more accurate representations of intracellular conditions [2] [1]. The integration of these constraints enables ecGEMs to predict biologically critical phenomena that traditional GEMs cannot capture, including metabolic overflow, resource allocation trade-offs, and substrate hierarchy utilization [2] [3] [1].

Fundamental Concepts and Theoretical Framework

Key Constraints in ecGEMs

ecGEMs enhance traditional stoichiometric models through several fundamental constraints:

Enzyme Catalytic Capacity: Each enzyme's maximum flux is limited by its turnover number (kcat) and concentration, governed by the relationship: ( vi \leq k{cat,i} \times [Ei] ), where ( vi ) is the metabolic flux through reaction i, ( k{cat,i} ) is the turnover number, and ( [Ei] ) is the enzyme concentration [2] [4].

Proteome Allocation: The total cellular enzyme capacity is constrained by the upper limit on protein synthesis, expressed as: ( \sum \frac{vi}{k{cat,i}} \times MWi \leq P{total} ), where MWi is the molecular weight of the enzyme catalyzing reaction i, and Ptotal is the total protein mass fraction available for metabolic functions [2] [1].

Molecular Crowding: The physical space occupied by enzymes within the cell imposes additional constraints on maximum enzyme concentrations, particularly in densely packed cellular environments [1].

Computational Methodologies for ecGEM Construction

Several computational frameworks have been developed to systematically incorporate enzyme constraints into GEMs:

Table 1: Computational Methods for ecGEM Construction

| Method | Key Features | Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| GECKO | Expands stoichiometric matrix with enzyme usage pseudo-reactions; incorporates kcat values and enzyme mass balances | Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Yarrowia lipolytica | [1] |

| MOMENT | Integrates protein molecular weights and catalytic rates; considers enzyme capacity constraints | Escherichia coli | [1] |

| AutoPACMEN | Automatically retrieves enzyme kinetic parameters from BRENDA and SABIO-RK databases | Escherichia coli | [2] [1] |

| ECMpy | Python-based workflow; adds enzyme capacity constraints without modifying stoichiometric matrix | Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, Corynebacterium glutamicum | [2] [1] |

| FBAwMC | Incorporates molecular crowding constraints through crowding coefficients | Early foundational approach | [1] |

Protocol for Constructing ecGEMs

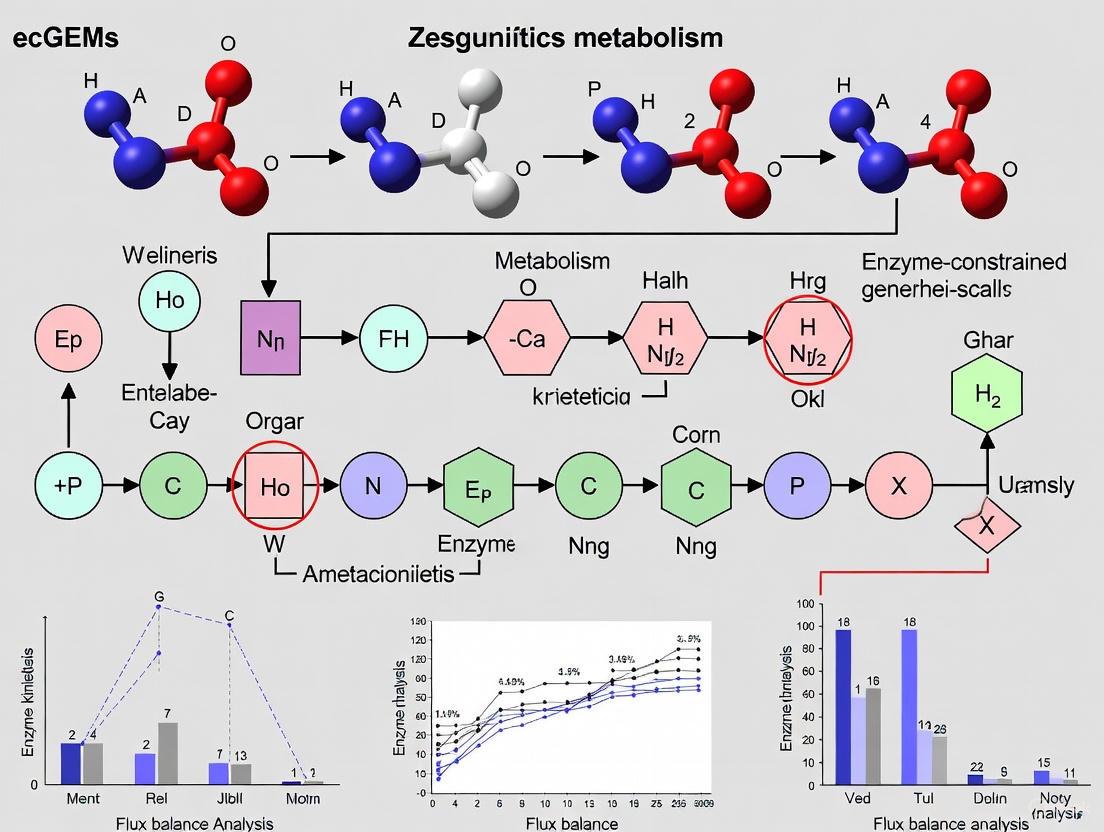

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for constructing enzyme-constrained metabolic models:

Phase 1: GEM Refinement and Quality Control

Before implementing enzyme constraints, the base GEM must undergo rigorous refinement to ensure biological accuracy and compatibility with ecGEM frameworks.

Biomass Composition Adjustment

- Experimental Measurement: Determine precise cellular composition through analytical methods. For Myceliophthora thermophila, researchers quantified RNA and DNA content by growing the wild-type strain on Vogel's minimal medium with 2% glucose, then performing UV spectrophotometry on extracted nucleic acids [3].

- Component Balancing: Adjust biomass constituents based on experimental data, including:

- Macromolecular ratios: Protein, RNA, DNA, lipid, and carbohydrate fractions

- Cofactor concentrations: Essential vitamins and minerals

- Cell wall composition: Species-specific structural components [3]

Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) Rule Correction

- Quantitative Subunit Composition: Correct GPR relationships to accurately represent protein complex stoichiometry using tools like GPRuler, enhanced with expanded terminology for complex identification (e.g., "component," "binding protein," "assembly factor") [1].

- Sequence Similarity Analysis: Identify and correct erroneous 'and' relationships by calculating protein sequence similarity; convert to 'or' relationships when similarity indicates isoenzymes rather than complex subunits [1].

- Manual Curation: Verify GPR rules against biochemical databases (KEGG, BioCyc) and literature evidence for metabolic pathways, particularly central carbon metabolism and energy generation pathways [3].

Metabolite and Reaction Standardization

- Identifier Mapping: Consolidate metabolite identifiers and names to standard nomenclature systems (BiGG, KEGG) to ensure compatibility with enzyme constraint frameworks [3].

- Charge and Formula Balance: Verify reaction stoichiometry for mass and charge conservation.

- Compartmentalization: Ensure accurate subcellular localization of metabolites and reactions.

Phase 2: Enzyme Kinetic Data Collection

Acquiring accurate enzyme kinetic parameters is crucial for ecGEM performance. Multiple approaches exist for kcat value determination:

Experimental kcat Acquisition

- Database Mining: Extract experimentally measured kcat values from specialized databases:

- Literature Curation: Manually extract kinetic parameters from published biochemical studies.

- Experimental Determination: Perform enzyme assays under physiological conditions for high-priority reactions.

Computational kcat Prediction

When experimental data is limited, machine learning approaches provide high-throughput kcat prediction:

Table 2: Machine Learning Tools for kcat Prediction

| Tool | Methodology | Input Features | Performance | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLKcat | Deep learning combining graph neural networks (substrates) and convolutional neural networks (proteins) | Substrate structures (SMILES) and protein sequences | Pearson's r = 0.71-0.88 on test datasets; RMSE = 1.06 | Genome-scale kcat prediction for 343 yeast/fungi species [4] |

| TurNuP | Machine learning-based kcat prediction | Substrate structures and enzyme features | Better performance in ecGEM construction for M. thermophila compared to other methods [2] | |

| AutoPACMEN | Automated database mining with machine learning | Enzyme commission numbers and organism specificity | Automated construction of ecGEMs | Escherichia coli model construction [2] [1] |

The kcat prediction and integration process is visualized below:

Molecular Weight Determination

- Subunit Composition Analysis: Calculate accurate molecular weights for protein complexes:

- Homomeric complexes: Multiply monomer MW by subunit count

- Heteromeric complexes: Sum MW of all subunits with stoichiometric coefficients

- Database Integration: Extract protein sequence information from UniProt and compute molecular weights accordingly.

- Complex Stoichiometry: Incorporate quantitative subunit composition from biochemical literature and complex databases [1].

Phase 3: ecGEM Construction and Implementation

Enzyme Capacity Constraints

The core mathematical formulation for enzyme constraints varies by implementation framework:

ECMpy Implementation (simplified constraint addition):

Where vi is the flux through reaction i, kcati is the enzyme turnover number, MWi is the enzyme molecular weight, and Ptotal is the total enzyme capacity constraint [2].

GECKO Implementation (stoichiometric matrix expansion):

Where S is the stoichiometric matrix, v is the flux vector, and E_usage represents enzyme utilization [1].

Model Calibration and Parameterization

- Total Enzyme Capacity: Set the P_total constraint based on experimental measurements of cellular protein content.

- kcat Adjustment: Calibrate kcat values to improve prediction accuracy for known physiological states.

- Constraint Tightening: Iteratively refine constraints to eliminate infeasible flux distributions while maintaining biological functionality.

Phase 4: Model Validation and Testing

- Growth Rate Prediction: Validate model predictions against experimental growth rates under various nutrient conditions.

- Substrate Utilization: Test the model's ability to predict hierarchical substrate utilization patterns.

- Metabolic Phenotypes: Verify prediction of known metabolic behaviors, such as overflow metabolism and enzyme efficiency trade-offs.

- Omics Data Integration: Compare model predictions with experimental proteomic and fluxomic data.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Tools for ecGEM Construction

| Category | Item/Resource | Specification/Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Materials | Vogel's Minimal Medium | Defined minimal medium for fungal cultivation | M. thermophila culture for biomass composition [3] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Buffers | TNE buffer, phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol | RNA/DNA quantification for biomass refinement [3] | |

| Lyophilization Equipment | Freeze-drying for biomass dry weight measurement | Determination of cellular macromolecular composition [3] | |

| Computational Tools | ECMpy Python Package | Automated ecGEM construction workflow | Corynebacterium glutamicum ecGEM development [1] |

| GPRuler Tool | Identification and correction of GPR relationships | Quantitative subunit composition analysis [1] | |

| DLKcat Package | Deep learning-based kcat prediction from sequences | Genome-scale kcat prediction for yeast species [4] | |

| AutoPACMEN | Automated retrieval of enzyme kinetic parameters | Escherichia coli ecGEM construction [1] | |

| Data Resources | BRENDA Database | Comprehensive enzyme kinetic parameter collection | Experimentally derived kcat values [4] [1] |

| SABIO-RK Database | Biochemical reaction kinetic parameters | Enzyme kinetic data for ecGEM constraints [4] [1] | |

| UniProt Database | Protein sequence and functional information | Molecular weight and subunit information [1] | |

| BiGG Models Database | Curated genome-scale metabolic models | Metabolite and reaction standardization [3] |

Applications and Case Studies

Metabolic Engineering ofMyceliophthora thermophila

The construction of ecMTM, an enzyme-constrained model for M. thermophila, demonstrated the practical utility of ecGEMs in industrial biotechnology. Researchers developed three ecGEM versions using different kcat collection methods (AutoPACMEN, DLKcat, and TurNuP), with the TurNuP-based model selected as the final ecMTM due to superior performance [2]. Key achievements included:

- Prediction of Metabolic Trade-offs: ecMTM revealed a trade-off between biomass yield and enzyme usage efficiency at varying glucose uptake rates, explaining cellular resource allocation strategies [2] [3].

- Substrate Hierarchy Utilization: The model accurately captured and explained the hierarchical utilization of five carbon sources from plant biomass hydrolysis, identifying enzyme limitation as the underlying mechanism [2].

- Metabolic Engineering Targets: Based on enzyme cost considerations, ecMTM successfully predicted known engineering targets and proposed novel modifications for chemical production in M. thermophila [2].

2Corynebacterium glutamicumfor Amino Acid Production

The development of ecCGL1, the first enzyme-constrained model for C. glutamicum, showcased the application of ecGEMs in amino acid production optimization. The model construction involved meticulous correction of GPR relationships and subunit composition, addressing critical limitations in previous models [1]. Notable outcomes included:

- Overflow Metabolism Simulation: ecCGL1 successfully simulated metabolic overflow phenomena, which traditional GEMs failed to predict, by accounting for proteomic limitations [1].

- Engineering Target Identification: The model identified several gene modification targets for L-lysine production, most of which aligned with previously reported genes, validating the approach [1].

- Improved Phenotype Prediction: ecCGL1 demonstrated enhanced accuracy in predicting cellular phenotypes compared to the base GEM, particularly under different nutrient conditions [1].

Pan-Genome Scale Modeling for Green Algae

Recent advances have extended ecGEM methodologies to pan-genome scale modeling, exemplified by the construction of an enzyme-constrained model for Chlorella ohadii, the fastest-growing green alga known [5]. This approach enabled:

- Comparative Flux Analysis: Identification of potential targets for growth improvement under standard and extreme light conditions through flux-based comparison with existing algal models [5].

- De Novo Model Reconstruction: Development of a semi-automated platform for generating genome-scale algal metabolic models, facilitating systematic identification of engineering targets [5].

- Condition-Specific Optimization: Model-driven discovery of metabolic adaptations underlying exceptional growth performance in extreme environments [5].

Future Perspectives and Development

The field of enzyme-constrained metabolic modeling continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising directions for advancement:

- Multi-Omics Data Integration: Incorporating transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data to create condition-specific ecGEMs with enhanced predictive accuracy [6].

- Machine Learning Enhancement: Expanding deep learning approaches to predict missing enzyme parameters and improve kcat value accuracy across diverse organisms [2] [4].

- Dynamic ecGEM Development: Extending static models to dynamic frameworks that simulate metabolic adaptations over time and under changing environmental conditions.

- Pan-Genome Applications: Scaling ecGEM reconstruction to pan-genome levels to capture metabolic diversity within species and identify conserved optimization principles [5].

As ecGEM methodologies become more sophisticated and accessible, they are poised to transform metabolic engineering and systems biology, providing unprecedented insights into the fundamental principles governing cellular resource allocation and metabolic efficiency.

Enzyme-constrained genome-scale metabolic models (ecGEMs) represent a significant advancement over traditional stoichiometric models by incorporating two critical biochemical parameters: enzyme turnover numbers (kcat) and enzyme abundances. These constraints enable a more accurate simulation of cellular metabolism by directly linking metabolic flux to proteomic allocation [4] [7]. The core principle governing ecGEMs is that the flux (v_j) of any enzyme-catalyzed reaction j is bounded by the product of the enzyme's turnover number and its concentration [E_i]: v_j ≤ kcat_ij ∙ [E_i] [8] [9]. This relationship forms the foundation for understanding proteome-limited metabolic behaviors, such as overflow metabolism and metabolic switches, which are poorly predicted by standard models [7] [9]. The integration of kcat values and enzyme abundance data allows ecGEMs to predict cellular phenotypes, proteome allocation, and physiological diversity with remarkable accuracy, making them indispensable tools in systems biology, metabolic engineering, and drug development [4] [10] [11].

Fundamental Concepts:kcatand Enzyme Abundance

The Enzyme Turnover Number (kcat)

The enzyme turnover number, kcat, is a first-order rate constant that defines the maximum number of substrate molecules an enzyme can convert to product per unit time per active site when fully saturated. It is a direct measure of an enzyme's catalytic efficiency [4] [11]. In ecGEMs, kcat values set the upper limit for the flux through a reaction for a given enzyme concentration, creating a direct link between enzyme kinetics and metabolic network flux [12] [9]. Traditionally, kcat values have been obtained from enzyme kinetics databases like BRENDA and SABIO-RK, but their coverage is sparse and often noisy due to varying experimental conditions [4] [13].

Enzyme Abundance

Enzyme abundance refers to the cellular concentration of an enzyme, typically measured in millimoles per gram of dry cell weight (mmol/gDW) using quantitative proteomics techniques [8]. This parameter represents the investment a cell makes in a particular catalytic function. In ecGEMs, the total sum of all enzyme abundances, weighted by their molecular weights, is constrained by the total protein mass available in the cell [7] [9]. This global constraint forces the model to make trade-offs in enzyme allocation, mimicking the real-world resource allocation challenges faced by cells [8].

The Combined Impact on Metabolic Flux

The interplay between kcat and enzyme abundance is formalized in ecGEMs through the enzyme capacity constraint:

Where v_i is the flux of reaction i, MW_i is the molecular weight of the enzyme catalyzing the reaction, σ_i is the enzyme saturation coefficient, ptot is the total protein fraction, and f is the mass fraction of enzymes in the proteome [7]. This equation ensures that the total enzyme capacity required to support a set of metabolic fluxes does not exceed the available proteomic budget.

Table 1: Key Parameters in Enzyme-Constrained Models

| Parameter | Symbol | Unit | Biological Role | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnover Number | kcat |

s⁻¹ or h⁻¹ | Catalytic efficiency of an enzyme | BRENDA [4], SABIO-RK [4], Deep Learning Predictions [4] [13] |

| Enzyme Abundance | [E] |

mmol/gDW | Cellular concentration of an enzyme | Quantitative Proteomics [8], Prediction Tools [8] |

| Molecular Weight | MW |

g/mmol | Size of the enzyme protein | UniProt, Protein Databases |

| Saturation Coefficient | σ |

Dimensionless | Effective enzyme utilization factor | Experimental fitting, often ~0.5 [7] |

| Total Protein Mass | P or ptot |

g/gDW | Total protein content available | Proteomics measurements |

Methodologies for Parameter Acquisition and ecGEM Construction

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Determination

Protocol: Measuring Enzyme Kinetics forkcatDetermination

Objective: To experimentally determine the kcat value for a purified enzyme.

Reagents: Purified enzyme, substrate(s), appropriate buffer, cofactors, stop solution, detection reagent.

Procedure:

- Prepare a series of substrate concentrations covering a range below and above the estimated Km.

- Prepare enzyme solutions at a concentration where the initial velocity is linear with time and enzyme amount.

- For each substrate concentration, initiate the reaction by adding enzyme and incubate at optimal temperature and pH.

- Measure initial velocity by tracking product formation or substrate depletion over time.

- Fit the Michaelis-Menten equation to the data:

v = (Vmax * [S]) / (Km + [S]) - Calculate

kcatusing the relationship:kcat = Vmax / [E_total], where[E_total]is the molar concentration of active enzyme. Notes: Ensure enzyme stability during assay, use appropriate controls, and perform replicates for statistical reliability [11].

Protocol: Determining Absolute Enzyme Abundance via Quantitative Proteomics

Objective: To quantify the absolute abundance of enzymes in a cell lysate. Reagents: Cell culture, lysis buffer, protease inhibitors, protein standard, trypsin, isotopic labeling reagents. Procedure:

- Harvest cells at mid-log phase and lyse using appropriate method.

- Determine total protein concentration using a standard method.

- Digest proteins with trypsin to generate peptides.

- Use isotopic labeling or label-free methods with spike-in standards of known concentration.

- Analyze peptides via liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry.

- Quantify peptides against standards and calculate absolute protein amounts.

- Normalize to cell dry weight or total protein content to obtain values in mmol/gDW. Notes: Ensure complete lysis, maintain linear range of detection, and use appropriate normalization [8].

Computational Approaches for Large-Scale Parameter Prediction

Protocol: PredictingkcatValues Using Deep Learning

Objective: To predict kcat values for enzyme-substrate pairs using computational models.

Input Requirements: Protein sequence (FASTA format) and substrate structure (SMILES notation).

Workflow:

- Data Preparation: Compile training data from BRENDA and SABIO-RK with protein sequences, substrate structures, and measured

kcatvalues. - Feature Representation:

- Encode protein sequences using pretrained language models like ProtT5.

- Encode substrate structures using molecular graph neural networks or SMILES transformers.

- Model Training: Train a deep learning architecture (e.g., DLKcat) or ensemble method (e.g., UniKP) to map feature representations to

kcatvalues. - Validation: Evaluate model performance using cross-validation and independent test sets.

- Prediction: Apply trained model to new enzyme-substrate pairs of interest. Tools: DLKcat [4], UniKP [13], EF-UniKP (for environmental factors) [13].

Diagram 1: Computational workflow for kcat prediction using deep learning

Protocol: Constructing an ecGEM Using the ECMpy Workflow

Objective: To reconstruct an enzyme-constrained metabolic model from a standard GEM.

Input Requirements: Genome-scale metabolic model (SBML format), kcat values, enzyme molecular weights, total protein content measurement.

Workflow:

- Preprocessing: Split reversible reactions into forward and backward directions with separate

kcatvalues. - Enzyme Reaction Mapping: Match enzymes to reactions they catalyze, considering isoenzymes and enzyme complexes.

- Constraint Formulation: Implement the enzyme mass balance constraint:

∑ (v_i ∙ MW_i) / (kcat_i ∙ σ_i) ≤ ptot ∙ f - Parameter Calibration: Adjust

kcatvalues and saturation coefficients to match experimental growth rates and flux data. - Model Validation: Test the model's ability to predict overflow metabolism, growth on different carbon sources, and proteome allocation. Tools: ECMpy [7], AutoPACMEN [9], GECKO [8].

Table 2: Comparison of Computational Tools for kcat Prediction

| Tool | Methodology | Inputs | Key Features | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLKcat [4] | Deep Learning (GNN + CNN) | Protein sequence, Substrate structure | Predicts kcat for any organism; identifies impactful residues | RMSE: 1.06 (test set); Pearson's r: 0.88 (whole dataset) |

| UniKP [13] | Pretrained language models + Ensemble | Protein sequence, Substrate structure | Unified framework for kcat, Km, kcat/Km; handles environmental factors | R²: 0.68 (kcat test set); 20% improvement over DLKcat |

| EF-UniKP [13] | Two-layer ensemble | Protein sequence, Substrate structure, pH, Temperature | Incorporates environmental factors in predictions | Robust prediction under varying conditions |

Applications in Metabolic Engineering and Drug Development

Metabolic Engineering with OKO (Overcoming Kinetic rate Obstacles)

The OKO framework represents a novel constraint-based approach for designing metabolic engineering strategies that focus on modifying enzyme turnover numbers rather than enzyme abundances [12].

Protocol: Applying OKO for Metabolic Engineering

Objective: To identify kcat modifications that enhance production of a target metabolite while maintaining growth.

Input Requirements: ecGEM, wild-type enzyme abundances, target production rate.

Procedure:

- Wild-type Analysis: Determine maximum product yield and optimal growth rate in the wild-type model.

- Enzyme Usage Minimization: Identify protein allocation by minimizing total enzyme usage.

- Turnover Number Optimization: With fixed enzyme abundances from step 2, identify which

kcatvalues need modification to achieve target production. - Strategy Implementation: Select enzymes for engineering based on OKO predictions, prioritizing those with highest impact and feasibility. Application Example: OKO applied to E. coli and S. cerevisiae ecGEMs predicted strategies that at least doubled the production of over 40 compounds with minimal growth penalty [12].

Diagram 2: OKO workflow for metabolic engineering

Predicting Enzyme Allocation with PARROT

PARROT (Protein allocation Adjustment foR alteRnative envirOnmenTs) is a constraint-based approach for predicting condition-specific enzyme allocation using a reference proteomic state [8].

Protocol: Predicting Enzyme Abundance Across Conditions with PARROT Objective: To predict enzyme abundances in alternative growth conditions using a reference condition. Input Requirements: ecGEM, reference condition enzyme abundances, alternative condition constraints. Procedure:

- Reference State: Integrate experimental proteomics measurements for a reference condition.

- Alternative Constraints: Apply metabolic constraints (e.g., different carbon sources) for the target condition.

- Minimization: Minimize the distance (Manhattan or Euclidean) between reference and alternative enzyme allocation.

- Prediction: Obtain enzyme abundance predictions for the alternative condition. Performance: The PARROT variant minimizing Manhattan distance between reference and alternative enzyme allocation outperformed flux-based prediction methods for both E. coli and S. cerevisiae [8].

Applications in Drug Development and Toxicology

Enzyme kinetics plays a crucial role in drug development, particularly in understanding drug metabolism, pharmacokinetics, and toxicity [11] [14].

Key Applications:

- Drug-Target Interactions: Characterize the binding affinity and catalytic inhibition of drug candidates on their target enzymes.

- Metabolic Stability: Assess the turnover of drug compounds by metabolic enzymes (e.g., cytochrome P450 family).

- Drug-Drug Interactions: Predict interactions when multiple drugs compete for the same metabolic enzymes.

- Toxicology: Identify potential toxic metabolites resulting from enzyme-mediated biotransformation.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for ecGEM Research

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Examples/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Kinetics Databases | Source of experimental kcat values | BRENDA [4], SABIO-RK [4] |

| Protein Abundance Databases | Source of experimental enzyme concentrations | Proteomics data repositories, PaxDB |

| Deep Learning Models | Prediction of kinetic parameters | DLKcat [4], UniKP [13] |

| ecGEM Construction Tools | Automated model construction | ECMpy [7], AutoPACMEN [9], GECKO [8] |

| Metabolic Engineering Tools | Identification of enzyme targets | OKO [12] |

| Protein Allocation Predictors | Condition-specific enzyme abundance | PARROT [8] |

The integration of kcat values and enzyme abundance data into genome-scale metabolic models has transformed our ability to predict cellular phenotypes and design effective metabolic engineering strategies. The development of high-throughput experimental methods and sophisticated computational prediction tools has addressed the critical challenge of parameter acquisition, enabling the reconstruction of high-quality ecGEMs for diverse organisms. As these methods continue to mature, ecGEMs will play an increasingly important role in biotechnology, drug development, and fundamental biological research, providing a more complete understanding of the intricate relationship between enzyme kinetics, proteome allocation, and cellular physiology.

Cellular metabolism, the complex network of biochemical reactions that sustains life, operates under fundamental physical and biochemical constraints. Among these, the finite capacity of cells to synthesize and accommodate proteins represents a critical bottleneck that shapes metabolic phenotypes across diverse organisms, from bacteria to human cells. The development of enzyme-constrained genome-scale metabolic models (ecGEMs) has revolutionized our understanding of how protein allocation governs metabolic strategies, providing a computational framework to predict cellular behaviors under resource limitations [7] [15]. These models have revealed that seemingly suboptimal metabolic strategies, such as overflow metabolism in microorganisms and the Warburg effect in cancer cells, emerge as direct consequences of optimal protein resource allocation rather than as metabolic inefficiencies [16]. This application note examines the fundamental principles underlying protein allocation constraints, detailing experimental methodologies and computational tools that enable researchers to explore this fundamental aspect of cellular physiology.

Theoretical Foundation: Principles of Proteome-Limited Metabolism

The Global Constraint Principle

The global constraint principle posits that cellular growth is not limited by a single nutrient or biochemical reaction but by a network of constraints acting collectively [17]. This principle unifies two classic biological laws: Monod's equation, which describes microbial growth, and Liebig's law of the minimum, which states that growth is limited by the scarcest resource. The finite proteomic budget of cells creates a hierarchical limitation system where alleviating one constraint immediately causes another to become dominant, resulting in the characteristic diminishing returns observed in microbial growth curves as nutrient availability increases [17].

Molecular Crowding and Spatial Constraints

Cellular geometry imposes profound constraints on metabolic function through molecular crowding effects. The distinction between two-dimensional membrane crowding and three-dimensional cytosolic crowding creates complementary limitations that shape metabolic strategies [18]. Membrane-associated processes face unique constraints due to the limited surface area available for embedding transport proteins and respiratory complexes. Studies of Escherichia coli K-12 strains with differing surface area to volume (SA:V) ratios have demonstrated that these biophysical parameters directly influence maximum growth rates and the onset of overflow metabolism [18]. The finite lipid bilayer capacity to host embedded and adsorbed proteins creates a membrane protein crowding effect that constrains nutrient uptake and energy metabolism independently from cytosolic limitations.

Table 1: Fundamental Constraints Shaping Cellular Metabolism

| Constraint Type | Mathematical Representation | Biological Manifestation |

|---|---|---|

| Total Enzyme Capacity | ∑(vᵢ × MWᵢ)/(σᵢ × kcatᵢ) ≤ ptot × f [7] | Limited total enzymatic capacity per cell |

| Membrane Surface Area | sMSA = f(flux, area requirement, kcat) [18] | Restricted nutrient uptake and respiration |

| Cytosolic Crowding | Vmax ∝ 1/(1 - φcrowding) [16] | Reduced diffusion and reaction rates |

| Proteome Allocation | ϕmetabolism + ϕribosomes + ϕother = 1 [16] | Trade-offs between metabolic sectors |

Methodological Approaches: Experimental and Computational Frameworks

Enzyme-Constrained Metabolic Modeling (ecGEM)

The integration of enzyme constraints into genome-scale metabolic models has been facilitated by several complementary computational frameworks:

GECKO (Genome-scale model to account for Enzyme Constraints using Kinetic and Omics) enhances GEMs with detailed descriptions of enzyme demands for metabolic reactions, accounting for isoenzymes, promiscuous enzymes, and enzymatic complexes [15]. The GECKO 2.0 toolbox automates model construction and parameterization, enabling the development of ecModels for diverse organisms including Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Escherichia coli, and Homo sapiens [15].

ECMpy provides a simplified Python-based workflow that directly incorporates total enzyme amount constraints without modifying existing metabolic reactions or adding numerous pseudo-reactions [7]. This approach maintains model simplicity while capturing the essential features of proteome-limited metabolism.

Constraint-based analysis of multireaction dependencies explores how forced balancing of metabolic complexes creates higher-order functional relationships between reaction fluxes, revealing potential targets for metabolic engineering [19].

Diagram 1: ecGEM Construction and Simulation Workflow. The workflow integrates stoichiometric models with enzyme kinetic data to generate predictive models of proteome-limited metabolism.

Quantitative Framework for Enzyme Constraints

The core mathematical formulation for enzyme constraints in metabolic models centers on the enzyme resource balance:

[ \sum{i=1}^{n} \frac{vi \cdot MWi}{\sigmai \cdot kcati} \leq p{tot} \cdot f ]

Where (vi) represents the flux through reaction i, (MWi) is the molecular weight of the enzyme catalyzing the reaction, (\sigmai) is the enzyme saturation coefficient, (kcati) is the turnover number, (p_{tot}) is the total protein fraction, and (f) is the mass fraction of enzymes in the proteome [7]. This fundamental inequality captures the trade-off between metabolic flux and proteomic investment that underlies resource allocation strategies.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for ecGEM Research

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Enzyme-Constrained Modeling

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GECKO Toolbox | MATLAB-based framework for enhancing GEMs with enzyme constraints | Construction of ecModels for diverse organisms [15] |

| ECMpy | Python-based workflow for enzyme-constrained model construction | Simplified implementation without modifying reaction structures [7] |

| BRENDA Database | Comprehensive collection of enzyme kinetic parameters | Source of kcat values for enzyme constraint parameterization [7] [15] |

| SABIO-RK | Database for biochemical reaction kinetics | Supplementary source of kinetic parameters [7] |

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB package for constraint-based modeling | Simulation and analysis of ecGEMs [15] |

| COBRApy | Python implementation of COBRA tools | Simulation of ecGEMs in Python environment [15] |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for ecGEM Development and Validation

Protocol: Construction of Enzyme-Constrained Models Using ECMpy

Principle: This protocol outlines the steps for constructing an enzyme-constrained metabolic model using the ECMpy workflow, which directly incorporates enzyme capacity constraints without extensive model modification [7].

Materials:

- Genome-scale metabolic model (SBML format)

- ECMpy Python package (available at https://github.com/tibbdc/ECMpy)

- Enzyme kinetic parameters from BRENDA and SABIO-RK databases

- Proteomic data (if available) for organism-specific calibration

Procedure:

- Model Preprocessing: Split reversible reactions into forward and backward irreversible reactions to accommodate direction-specific kcat values.

- Kinetic Data Integration: Collect kcat values from BRENDA and SABIO-RK databases, prioritizing organism-specific measurements where available.

- Enzyme Mass Calculation: For reactions catalyzed by enzyme complexes, calculate the apparent kcat/MW ratio using the limiting subunit: (kcati/MWi = \min(kcat{ij}/MW{ij}, j∈m)) where m represents the number of proteins in the complex [7].

- Constraint Formulation: Implement the enzyme capacity constraint using the inequality: (\sum{i=1}^{n} \frac{vi \cdot MWi}{\sigmai \cdot kcati} \leq p{tot} \cdot f)

- Parameter Calibration: Adjust kcat values using two principles:

- Reactions with enzyme usage exceeding 1% of total enzyme content require correction

- Reactions where 10% of total enzyme amount × kcat is less than experimentally determined flux need adjustment [7]

- Model Validation: Compare predicted growth rates with experimental data across multiple nutrient conditions.

Applications: This protocol enables researchers to develop computational models that accurately predict overflow metabolism, substrate utilization patterns, and proteome allocation strategies [7].

Protocol: Analysis of Membrane Crowding Constraints

Principle: This methodology quantifies how membrane surface area limitations and protein crowding constrain metabolic functions, particularly in strains with different cellular geometries [18].

Materials:

- Bacterial strains with differing SA:V ratios (e.g., E. coli MG1655 vs. NCM3722)

- Proteomics data for membrane-associated proteins

- Cell dimension measurements (length, width) across growth rates

- Metabolic network reconstruction including transport reactions

Procedure:

- Cellular Geometry Quantification: Measure cell dimensions across growth rates to calculate strain-specific SA:V ratios.

- Membrane Proteome Analysis: Quantify copy numbers of membrane-associated proteins (transporters, respiratory complexes) using proteomics.

- Areal Density Calculation: Convert protein copy numbers to surface area occupation using known structural dimensions of membrane protein complexes.

- Specific Membrane Surface Area (sMSA) Determination: Calculate the membrane area required per unit cell weight to support observed metabolic fluxes: (sMSA = \frac{flux \times area\ requirement}{kcat}) [18]

- Crowding Constraint Implementation: Incorporate membrane surface limitations as additional constraints in metabolic models.

- Phenotypic Prediction: Validate model predictions against experimental growth rates and overflow metabolism thresholds.

Applications: This approach explains strain-specific differences in metabolic performance and identifies membrane crowding as a complementary constraint to cytosolic protein allocation [18].

Applications and Case Studies: Insights from Protein Allocation Constraints

Overflow Metabolism and the Warburg Effect

The application of ecGEMs has provided transformative insights into the long-standing puzzle of overflow metabolism - the seemingly wasteful production of fermentation products despite sufficient oxygen for complete respiration. Computational and experimental studies demonstrate that this metabolic strategy emerges from optimal protein allocation rather than kinetic or thermodynamic constraints [16]. When nutrient availability is high, the protein cost of maintaining high respiratory flux exceeds the cost of fermentative pathways combined with the burden of exporting partially oxidized products, leading to a proteomic optimality that favors overflow metabolism [16].

Table 3: Quantitative Predictions of ecGEMs for E. coli Metabolism

| Metabolic Function | Standard GEM Prediction | ecGEM Prediction | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetate Overflow Threshold | Incorrect or missing | ~0.4 h⁻¹ for MG1655 [18] | Consistent with culturing data |

| Maximum Growth Rate on Glucose | Overpredicted | 0.69 h⁻¹ for MG1655 [18] | Matches experimental measurements |

| Enzyme Allocation to Central Metabolism | Not predicted | 20-40% of proteome [16] | Aligns with proteomics studies |

| Growth Rate on 24 Carbon Sources | Poor correlation with experiments | Significant improvement [7] | R² = 0.85-0.95 |

Strain-Specific Metabolic Performance

EcGEMs incorporating cellular geometry constraints successfully explain phenotypic differences between closely related bacterial strains. E. coli NCM3722 exhibits approximately 40% faster maximum growth rates and higher overflow thresholds compared to MG1655, differences that correlate with their distinct SA:V ratios and membrane protein crowding patterns [18]. These findings highlight how biophysical constraints interact with metabolic network structure to determine strain-specific metabolic capabilities.

Diagram 2: Proteome Allocation Logic Leading to Overflow Metabolism. The cascade shows how nutrient availability ultimately drives the choice of metabolic strategy through proteomic constraints.

The integration of protein allocation constraints into metabolic models has transformed our understanding of cellular physiology, providing a unified framework that explains seemingly suboptimal metabolic strategies across diverse organisms. The enzyme allocation paradigm represents a fundamental advance in systems biology, connecting molecular-level constraints with organismal phenotypes. For metabolic engineers and therapeutic developers, ecGEMs offer powerful tools for identifying optimal genetic modifications that respect cellular resource allocation principles, enabling more predictable and efficient strain design and therapeutic targeting. As these approaches continue to evolve, incorporating additional layers of biological complexity, they promise to further bridge the gap between molecular mechanisms and physiological outcomes.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) have become established tools for systematic analysis of metabolism across a wide variety of organisms, with applications spanning from model-driven development of efficient cell factories to understanding mechanisms underlying complex human diseases [15] [20]. The most common simulation technique for these models is Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), which assumes balancing of fluxes around each metabolite in the metabolic network, constrained by reaction stoichiometries and optimality principles [15] [21].

However, classical FBA has a significant limitation: it predicts optimal phenotypes that can be attained by alternate flux distribution profiles due to network redundancies, creating challenges for quantitative determination of biologically meaningful flux distributions [15]. A major constraint missing from traditional FBA is the enzymatic limitations on metabolic reactions, which include kinetic parameters, physiological constraints like crowded intracellular volume, finite membrane surface area, and bounded total protein mass available for metabolic enzymes [15] [21].

This review traces the historical development from foundational FBA methods to more sophisticated enzyme-constrained frameworks, specifically the GECKO (Enhancement of GEMs with Enzymatic Constraints using Kinetic and Omics data) and MOMENT (Metabolic Optimization with Enzyme Kinetics and Metabolite Concentrations) approaches, which represent significant milestones in making metabolic models more predictive and physiologically realistic.

Foundations: Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and Its Limitations

Core Mathematical Framework of FBA

Flux Balance Analysis operates on the principle of mass balance at pseudo-steady state, mathematically represented as:

Objective: min or max z = Σ(cj × vj) for j ∈ J

Subject to: Σ(Sij × vj) = 0 for all i ∈ I vj^LB ≤ vj ≤ v_j^UB for all j ∈ J

Where:

- z is the objective variable (e.g., biomass production)

- J is the set of reactions

- c_j is a vector of objective weights for reaction j

- v_j is the flux through reaction j (in mmol gDW⁻¹ h⁻¹)

- I is the set of metabolites

- S_ij is the stoichiometric matrix

- vj^LB and vj^UB are lower and upper flux bounds [21]

Limitations of Traditional FBA

While SMMs using FBA have been successfully applied to numerous research questions, they face several critical limitations:

- No explicit protein costs: Beyond bulk contribution to biomass, SMMs do not directly track the metabolic costs of protein synthesis [21].

- Missing mechanistic details: Models lack enzyme kinetic capacity, physical proteome limitations, crowding, degradation, and dilution through growth and cell division [21].

- Overly optimistic predictions: The absence of enzymatic constraints can lead to predictions that are not physiologically achievable [15] [21].

- Inability to explain overflow metabolism: Classical FBA struggles to explain phenomena like the Crabtree effect in yeast without additional constraints [15].

Table 1: Key Limitations of Traditional FBA and Solutions Provided by Advanced Frameworks

| Limitation of Traditional FBA | Solution in Enzyme-Constrained Models | Framework Addressing It |

|---|---|---|

| No explicit enzyme capacity constraints | Incorporation of kcat values and enzyme mass balances | GECKO, MOMENT |

| No proteome allocation constraints | Total protein pool constraint | GECKO |

| Inability to predict protein allocation | Enzyme usage pseudo-reactions | GECKO |

| Poor prediction of overflow metabolism | Enzyme resource scarcity forces trade-offs | GECKO (ecYeast demonstrated this) |

| Limited integration of omics data | Direct incorporation of proteomics data | GECKO |

The Rise of Enzyme-Constrained Frameworks: GECKO and MOMENT

The GECKO Framework

The GECKO toolbox was first developed in 2017 and represents a significant advancement in incorporating enzymatic constraints into GEMs [15] [22]. The method extends classical FBA by incorporating a detailed description of enzyme demands for metabolic reactions, accounting for all types of enzyme-reaction relations including isoenzymes, promiscuous enzymes, and enzymatic complexes [15].

GECKO enhances GEMs through several key innovations:

- Enzyme constraints: Incorporates enzyme capacity constraints using kcat values from databases like BRENDA [15] [22].

- Proteomics integration: Enables direct integration of proteomics abundance data as constraints for individual protein demands [15].

- Automated parameter retrieval: Implements hierarchical procedures for retrieving kinetic parameters, initially achieving high coverage for S. cerevisiae models [15].

- Unmeasured enzyme handling: All unmeasured enzymes in the network are constrained by a pool of remaining protein mass [15].

The first implementation of GECKO was applied to the consensus GEM for S. cerevisiae, Yeast7, resulting in the enzyme-constrained model ecYeast7, which successfully predicted the Crabtree effect in wild-type and mutant strains and improved predictions of cellular growth across diverse environments and genetic backgrounds [15].

GECKO 2.0: Enhanced Capabilities

In 2022, GECKO was upgraded to version 2.0 with significant improvements [15]:

- Generalized structure: Enhanced applicability to a wide variety of GEMs beyond yeast [15].

- Improved parameterization: Better coverage of kinetic constraints even for poorly studied organisms [15].

- Simulation utilities: Added functions for model simulation and analysis [15].

- Automated pipeline: Development of ecModels container for continuously updated catalog of diverse ecModels [15].

- Community development: Established as open-source software with continuous development tracking in a public repository [15].

The MOMENT Framework

The MOMENT (Metabolic Optimization with Enzyme Kinetics and Metabolite Concentrations) framework represents another approach to integrating enzyme constraints into metabolic models [22]. Like GECKO, MOMENT introduces constraints based on enzyme concentrations, catalytic efficiency, and molecular weight [22].

Key features of MOMENT include:

- Enzyme allocation constraints: Considers the proteomic constraints on metabolic fluxes.

- Integration with enzyme data: Similar to GECKO, incorporates information from kinetic databases.

- Applications across organisms: Has been applied to various microbial systems.

A significant development was the combination of MOMENT and GECKO principles into AutoPACMEN, a method capable of automatically retrieving enzyme data from BRENDA and SABIO-RK databases, representing an important step in automating ecGEM construction [22].

Practical Protocols: Implementing Enzyme-Constrained Models

Protocol for Constructing ecGEMs Using GECKO

Objective: Enhance a standard GEM with enzymatic constraints using the GECKO toolbox. Estimated Duration: 2-4 weeks depending on model complexity and available data.

Table 2: Step-by-Step Protocol for GECKO Implementation

| Step | Procedure | Key Considerations | Expected Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Model Preparation | Ensure GEM is in compatible format (COBRA or RAVEN). Check mass and charge balances. | Format conversion may be needed from XML to JSON for some workflows [22]. | Standardized model ready for enhancement. |

| 2. kcat Collection | Use hierarchical matching: organism-specific → non-specific → enzyme class-based kcats. | GECKO 2.0 implements modified matching criteria for better coverage [15]. | kcat values for maximum possible reactions. |

| 3. Model Expansion | Add enzyme pseudoreactions and constraints using GECKO functions. | Account for isoenzymes, complexes, and multifunctional enzymes [15]. | Expanded S-matrix with enzyme constraints. |

| 4. Proteomics Integration | Incorporate proteomics data if available as additional constraints. | Unmeasured enzymes constrained by remaining protein pool [15]. | Further constrained solution space. |

| 5. Model Validation | Test predictions against experimental growth and flux data. | Compare with classical FBA predictions to verify improvement [15] [22]. | Validated ecGEM with improved accuracy. |

Protocol for ecGEM Construction via ECMpy

Objective: Construct enzyme-constrained model using the automated ECMpy workflow. Estimated Duration: 1-3 weeks.

The ECMpy workflow, demonstrated for constructing an ecGEM for Myceliophthora thermophila, provides an alternative automated approach [22]:

- Model Refinement: Update and modify the base GEM (e.g., adjust biomass components, correct GPR rules, consolidate metabolites) [22].

- kcat Data Collection: Gather enzyme turnover numbers using multiple methods (AutoPACMEN, DLKcat, TurNuP) [22].

- Model Comparison: Test different ecGEM versions based on kcat collection methods and select the best performer [22].

- Simulation & Validation: Run growth simulations and compare predictions to experimental data to ensure improved accuracy [22].

Applications and Case Studies

Successful Implementations

Enzyme-constrained models have demonstrated significant improvements in predictive capability across various organisms:

S. cerevisiae: The original ecYeast7 model successfully predicted the Crabtree effect and cellular growth on diverse environments [15]. The model also formed the basis for modeling yeast growth at different temperatures [15].

E. coli and B. subtilis: GECKO principles have been incorporated into models for these bacteria, showing improved phenotype predictions [15].

Human cell-lines: Enzyme-constrained models have been developed for human cancer cell-lines, expanding applications to medical research [15].

Myceliophthora thermophila: Construction of ecMTM using machine learning-based kcat data accurately captured hierarchical utilization of carbon sources and predicted metabolic engineering targets [22].

Non-model yeasts: Enzyme-constrained approaches have been applied to yeasts like Yarrowia lipolytica and Kluyveromyces marxianus to study long-term adaptation to stress factors [15].

Quantitative Improvements in Predictions

The implementation of enzyme constraints has consistently demonstrated quantitative improvements over traditional FBA:

- Reduced solution space: ecGEMs significantly narrow the range of possible flux distributions [22].

- More realistic phenotypes: Predictions of growth rates and metabolic fluxes better match experimental measurements [15] [22].

- Trade-off identification: ecMTM revealed trade-offs between biomass yield and enzyme usage efficiency at varying glucose uptake rates [22].

- Metabolic adaptation: ecGEMs successfully explain metabolic adaptations to stress and nutrient limitations [15].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ecGEM Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| GECKO Toolbox | MATLAB software | Enhances GEMs with enzymatic constraints | Construction of ecYeast from Yeast GEM [15] |

| ECMpy | Python package | Automated construction of ecGEMs | Building ecGEM for M. thermophila [22] |

| BRENDA Database | Kinetic database | Source of enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat) | Parameterizing enzyme constraints in GECKO [15] |

| AutoPACMEN | Automated tool | Retrieves enzyme data from BRENDA/SABIO-RK | Automated ecGEM construction [22] |

| TurNuP | Machine learning tool | Predicts kcat values using ML | kcat prediction for less-studied organisms [22] |

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB package | Constraint-based reconstruction & analysis | Simulation and analysis of ecGEMs [15] |

| RAVEN Toolbox | MATLAB package | Reconstruction, analysis and visualization of networks | Automated reconstruction of draft GEMs [20] |

Visualization of Framework Relationships and Workflows

Historical Development and Relationships

Framework Evolution - Historical development from FBA to modern enzyme-constrained frameworks.

GECKO Model Enhancement Workflow

GECKO Workflow - Process for enhancing a base GEM with enzymatic constraints using the GECKO toolbox.

The development from FBA to GECKO and MOMENT represents a significant evolution in constraint-based metabolic modeling. The incorporation of enzyme constraints has addressed fundamental limitations of traditional FBA, resulting in more accurate and physiologically realistic predictions. The creation of automated toolboxes like GECKO 2.0 and ECMpy has democratized access to these advanced modeling techniques, enabling broader adoption across the research community.

Future directions in this field include:

- Improved parameter estimation: Machine learning approaches like TurNuP show promise for kcat prediction, especially for less-studied organisms [22].

- Standardization: Community standards for terminology and framework evaluation are needed as the field matures [21].

- Integration with multi-omics: Further incorporation of transcriptomics, metabolomics, and proteomics data will continue to enhance model accuracy [20].

- Expansion to new organisms: Application to non-model organisms with industrial or medical relevance [15] [20].

The historical progression from FBA to enzyme-constrained frameworks has transformed genome-scale metabolic modeling from a primarily stoichiometric analysis to a more comprehensive representation of cellular physiology that accounts for the critical constraints of protein allocation and enzyme kinetics. As these frameworks continue to evolve, they promise to further enhance our ability to predict cellular behavior and engineer biological systems for biomedical and biotechnological applications.

Methodologies and Real-World Applications Across Organisms

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) have become established tools for systematic analysis of metabolism across diverse organisms, enabling the prediction of cellular phenotypes from genetic information [15]. However, traditional constraint-based models, which rely primarily on stoichiometric constraints and flux balances, often overlook a critical biological limitation: the finite capacity of cells to produce and allocate enzymatic proteins. This limitation can lead to inaccurate flux predictions and an overestimation of metabolic capabilities. Enzyme-constrained genome-scale metabolic models (ecGEMs) address this gap by incorporating enzymatic constraints using kinetic parameters (e.g., turnover numbers ( k_{cat} )) and enzyme mass considerations, thereby providing a more realistic representation of cellular metabolism [9] [15].

The integration of enzyme constraints has been shown to significantly improve the predictive accuracy of metabolic models. For instance, ecGEMs can simulate overflow metabolism (e.g., the Crabtree effect in yeast) and other metabolic switches without explicitly bounding substrate uptake rates, explaining phenomena that are poorly predicted by standard GEMs [23] [9]. Over the past decade, several computational toolboxes have been developed to facilitate the construction of ecGEMs. Among these, GECKO (Enhancement of GEMs with Enzymatic Constraints using Kinetic and Omics data), AutoPACMEN (Automatic integration of Protein Allocation Constraints in MEtabolic Networks), and sMOMENT (short MOMENT) represent prominent methodologies. These tools help researchers enhance existing GEMs by incorporating enzyme constraints, thereby narrowing the solution space of feasible flux distributions and yielding more biologically accurate predictions [9] [22] [24].

This article provides a detailed overview of these three toolboxes, comparing their methodologies, applications, and protocols to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the appropriate tools for their ecGEM projects.

The field of enzyme-constrained modeling has evolved from early frameworks like Flux Balance Analysis with Molecular Crowding (FBAwMC) and MOMENT (Metabolic Modeling with Enzyme Kinetics) into more automated and user-friendly toolboxes [9] [24]. The following sections and Table 1 provide a comparative summary of the GECKO, AutoPACMEN, and sMOMENT toolboxes.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of ecGEM Toolboxes

| Feature | GECKO | AutoPACMEN | sMOMENT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Methodology | Expands the stoichiometric matrix (S-matrix) with reactions for enzyme usage [22]. | Simplifies the MOMENT approach; constraints are directly embedded into the S-matrix [9]. | A simplified, more computationally efficient version of MOMENT [9]. |

| Mathematical Problem | Linear Programming (LP) [24] | Quadratic Programming (QP) [24] | Quadratic Programming (QP) [24] |

| Key Constraints | Enzyme capacity via a total protein pool and/or individual enzyme limits from proteomics data [23]. | Enzyme mass constraints drawing from a total cellular protein pool [9]. | Enzyme mass constraints via a pooled enzyme resource [9]. |

| Automation & Inputs | Automated parameter retrieval from BRENDA; supports integration of omics data [15]. | Automated creation from a stoichiometric model; automatic read-out of enzymatic data from SABIO-RK and BRENDA [9]. | Not specified in search results, but builds upon MOMENT principles. |

| Typical Applications | Prediction of overflow metabolism, proteome allocation, strain design in yeast, E. coli, and humans [23] [15]. | Overflow metabolism, prediction of metabolic engineering strategies in E. coli [9]. | Overflow metabolism, improved flux predictions [9]. |

The GECKO Toolbox

The GECKO toolbox is a robust method for enhancing a GEM to account for enzyme constraints using kinetics and omics data. Its core principle involves expanding the original GEM's stoichiometric matrix (S-matrix) by adding new rows representing enzymes and new columns representing enzyme usage reactions. This explicit representation allows for the direct incorporation of measured enzyme concentrations from proteomics data as upper limits for flux capacities [23] [22]. A major strength of GECKO is its high level of automation and community-driven development. The toolbox includes functions for automatically retrieving enzyme kinetic parameters (( k_{cat} )) from the BRENDA database, and it can handle various enzyme-reaction relationships, including isoenzymes, enzyme complexes, and promiscuous enzymes [15]. GECKO has been successfully applied to a wide range of organisms, including Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Escherichia coli, and Homo sapiens, to study phenomena like the Crabtree effect and to guide metabolic engineering designs [23] [15] [25].

The AutoPACMEN Toolbox

AutoPACMEN was developed to enable an almost fully automated creation of enzyme-constrained models. It implements the sMOMENT method, which is a simplified version of the earlier MOMENT approach. The key simplification lies in its mathematical formulation: instead of introducing a separate variable ( gi ) for each enzyme concentration, sMOMENT substitutes the enzyme constraint directly into the protein pool equation. This results in a single, aggregated constraint on the metabolic fluxes: ( \sum vi \cdot \frac{MWi}{k{cat,i}} \leq P ), where ( vi ) is the flux, ( MWi ) is the molecular weight of the enzyme, ( k_{cat,i} ) is the turnover number, and ( P ) is the total protein pool [9]. This formulation requires considerably fewer variables and allows the enzymatic constraints to be directly incorporated into the standard representation of a constraint-based model, making it compatible with standard simulation tools [9]. AutoPACMEN automates the process of gathering the necessary enzymatic data from databases like BRENDA and SABIO-RK and reconfiguring the stoichiometric model. It has been used, for example, to generate an enzyme-constrained version of the E. coli iJO1366 model, demonstrating improved predictions of overflow metabolism and revealing altered metabolic engineering strategies [9].

The sMOMENT Methodology

The sMOMENT (short MOMENT) method is the mathematical core of the AutoPACMEN toolbox. As a simplified version of MOMENT, it achieves the same predictive goals but with a more compact representation that reduces computational demand [9]. The primary innovation of sMOMENT is the derivation of a unified enzyme capacity constraint. By combining the enzyme kinetic constraint (( vi \leq k{cat,i} \cdot gi )) and the total protein pool constraint (( \sum gi \cdot MWi \leq P )), it eliminates the intermediate enzyme concentration variables (( gi )). The resulting constraint, ( \sum vi \cdot \frac{MWi}{k_{cat,i}} \leq P ), can be integrated into the model as a single additional reaction drawing from a pooled protein resource [9]. This approach not only makes the model smaller and faster to solve but also allows it to be treated with standard constraint-based modeling software, increasing its accessibility for routine analysis [9].

Workflow for ecGEM Construction

The process of constructing an ecGEM, while varying in specifics between toolboxes, follows a general logical pipeline. The diagram below illustrates the key stages and decision points involved in this process.

Protocol 1: Model Curation and Preparation

Before implementing enzyme constraints, the underlying GEM must be rigorously curated to ensure its quality and compatibility with the chosen toolbox.

- Action 1: Update Biomass Composition. Adjust the biomass objective function to reflect experimentally determined cellular composition. For example, in constructing an ecGEM for Myceliophthora thermophila, researchers quantified RNA and DNA content experimentally and updated the model accordingly [22].

- Action 2: Correct Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) Rules. Review and update GPR associations based on the latest genome annotation and experimental evidence. This step is critical as GPR rules directly link metabolic reactions to enzyme usage. Corrections might involve adding missing isoenzymes or correcting subunit compositions of enzyme complexes [22].

- Action 3: Consolidate Metabolites and Format Conversion. Identify and merge redundant metabolite entries to ensure network consistency. Furthermore, some toolboxes require specific model formats (e.g., ECMpy requires models in JSON format), so file conversion may be necessary [22].

Protocol 2: Acquisition of Enzyme Kinetic Parameters (( k_{cat} ))

The collection of accurate enzyme turnover numbers (( k_{cat} )) is a pivotal step in ecGEM construction. The choice of method can significantly impact model performance, as shown in Table 2.

- Action 1: Database-Driven Curation. Use automated tools within GECKO and AutoPACMEN to query kinetic databases like BRENDA and SABIO-RK. This method prioritizes organism-specific ( k_{cat} ) values but may suffer from low coverage for less-studied organisms [9] [15].

- Action 2: Machine Learning-Based Prediction. For non-model organisms with limited characterized enzymes, leverage machine learning tools such as TurNuP, DLKcat, or UniKP to predict ( k{cat} ) values. Studies have shown that models built with predicted ( k{cat} ) values, particularly from TurNuP, can outperform those relying on database-derived values from other organisms [22] [25].

- Action 3: Parameter Selection and Gap-Filling. Implement a hierarchical decision pipeline to select the best available ( k{cat} ) for each reaction, prioritizing organism-specific experimental values, followed by values from closely related species, and finally, predicted values. Reactions without any ( k{cat} ) data may require manual curation or the use of a global default value [15].

Table 2: Common Sources for kcat Data in ecGEM Construction

| Data Source | Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| BRENDA/SABIO-RK | Manually curated databases of enzyme kinetic parameters. Primary source for GECKO and AutoPACMEN [9] [15]. | Used in the construction of ecYeast7 and the sMOMENT model of E. coli iJO1366 [9] [15]. |

| TurNuP | A machine learning tool for predicting ( k_{cat} ) values [22]. | Used to construct ecMTM, the ecGEM for Myceliophthora thermophila, where it yielded better performance than other methods [22]. |

| DLKcat | A deep learning-based predictor for ( k_{cat} ) values [25]. | Evaluated for the construction of an ecGEM for Zymomonas mobilis [25]. |

| AutoPACMEN | Automatically retrieves and processes ( k_{cat} ) data from BRENDA and SABIO-RK [9]. | Used to generate the enzyme-constrained model eciZM547 for Zymomonas mobilis [25]. |

Protocol 3: Implementation with the GECKO Toolbox

The following protocol is based on GECKO 3.0 and its accompanying Nature Protocols publication [23].

- Action 1: Toolbox Installation and Setup. Clone the GECKO repository from GitHub (https://github.com/SysBioChalmers/GECKO) and follow the installation instructions in the Wiki. Ensure dependencies like the COBRA Toolbox and a compatible MATLAB version are installed [23] [26].

- Action 2: Model Enhancement. Use the core GECKO functions to build the ecModel. This involves:

makeEcModel: Converts a standard GEM into a framework ecModel structure.getECfromGEM: Maps Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers to model reactions.getKcat: Populates the model with ( k{cat} ) values using the hierarchical querying system.applyKcatConstraints: Incorporates the ( k{cat} ) constraints into the model [23].

- Action 3: Integration of Proteomics Data. If proteomics data is available, use the

constrainEnzConcsfunction to set upper bounds for individual enzyme usage reactions based on measured protein concentrations. In GECKO 3.2.0 and later, all enzyme usage reactions draw from a common protein pool, making theupdateProtPoolfunction obsolete [23]. - Action 4: Simulation and Analysis. Simulate growth or production phenotypes using Flux Balance Analysis (FBA). The tutorials provided in the

GECKO/tutorialsfolder (e.g.,protocol.mfor full and light ecModels) offer detailed examples of how to run and analyze simulations [23].

Protocol 4: Implementation with AutoPACMEN/sMOMENT

This protocol outlines the use of AutoPACMEN for constructing an sMOMENT model [9].

- Action 1: Data Retrieval. Run the AutoPACMEN toolbox to automatically gather the required enzymatic data (( k_{cat} ) and molecular weights) for the target GEM from the SABIO-RK and BRENDA databases.

- Action 2: Model Reconstruction. The toolbox automatically reconfigures the stoichiometric model to embed the enzymatic constraints according to the sMOMENT principle. The key output is the addition of the enzyme capacity constraint (( \sum vi \cdot \frac{MWi}{k_{cat,i}} \leq P )) to the model.

- Action 3: Parameter Fitting (Optional). AutoPACMEN provides tools to adjust the parameters of the sMOMENT model (e.g., the total protein pool ( P ) or specific ( k_{cat} ) values) based on experimental flux data, which can further refine model accuracy [9].

- Action 4: Simulation. Utilize standard constraint-based modeling tools to perform simulations with the generated sMOMENT model. The simplified representation ensures compatibility and computational efficiency for analyses like FBA and flux variability analysis (FVA) [9].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Building and utilizing ecGEMs relies on a combination of computational tools, data resources, and model assets. The table below details key resources that form the essential "reagent solutions" for this field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for ecGEM Construction

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Function in ecGEM Research |

|---|---|---|

| BRENDA Database | Kinetic Database | Primary source for experimentally determined enzyme turnover numbers (( k_{cat} )) and kinetic parameters [9] [15]. |

| SABIO-RK Database | Kinetic Database | Another major repository for curated enzyme kinetic data, used by AutoPACMEN for automated parameter retrieval [9]. |

| COBRA Toolbox | Software Package | A fundamental MATLAB toolbox for constraint-based modeling. Used by GECKO for model simulation and analysis [15]. |

| TurNuP | Software Tool | A machine learning-based predictor for ( k_{cat} ) values; crucial for parameterizing ecGEMs of non-model organisms [22]. |

| ECMpy | Software Toolbox | An automated Python-based workflow for constructing ecGEMs, used as an alternative to GECKO [22] [25]. |

| Reference GEMs (e.g., iJO1366, Yeast8) | Model Asset | High-quality, community-curated genome-scale models that serve as the foundational input for enhancement into ecGEMs [9] [15]. |

Applications and Case Studies

The application of ecGEMs has led to significant advances in both basic science and metabolic engineering. Below are two illustrative case studies.

Case Study 1: Engineering Myceliophthora thermophila with ecMTM. Researchers constructed ecMTM, the first ecGEM for the thermophilic fungus M. thermophila, using machine learning-predicted ( k_{cat} ) values from TurNuP. Compared to the traditional GEM, ecMTM provided a more realistic representation of cellular physiology by revealing a trade-off between biomass yield and enzyme usage efficiency at different glucose uptake rates. Furthermore, the model accurately simulated the hierarchical utilization of multiple carbon sources and predicted new potential metabolic engineering targets for chemical production, demonstrating its value in guiding strain design [22].

Case Study 2: Developing a Biorefinery Chassis for Zymomonas mobilis. To overcome the innate dominant ethanol pathway in Z. mobilis, researchers updated the iZM516 GEM to iZM547 and then developed an enzyme-constrained model, eciZM547, using AutoPACMEN-derived ( k_{cat} ) values. This ecGEM accurately simulated a metabolic shift from glucose-limited to proteome-limited growth, a phenomenon overestimated by the traditional model. The insights from eciZM547 informed a "dominant-metabolism compromised intermediate-chassis" (DMCI) strategy, which successfully led to the construction of a high-yield D-lactate producer, showcasing the power of ecGEMs in rational chassis design [25].

The development of toolboxes like GECKO, AutoPACMEN, and sMOMENT has democratized the construction of enzyme-constrained metabolic models, moving them from specialized methodologies to accessible tools for the broader research community. Each toolbox offers distinct advantages: GECKO provides a detailed and explicit representation of enzyme usage with strong community support and continuous development; AutoPACMEN and its core method sMOMENT offer a simplified, computationally efficient, and automated pipeline that integrates seamlessly with standard modeling workflows.

The choice of toolbox depends on the research goals, the organism of interest, and the available data. For researchers seeking high detail and the ability to integrate specific proteomics data, GECKO is an excellent choice. For those prioritizing computational efficiency and automation, particularly for well-annotated model organisms, AutoPACMEN/sMOMENT is highly suitable. Furthermore, the emerging use of machine learning to predict kinetic parameters is bridging a critical data gap, making ecGEMs increasingly applicable to non-model organisms with poor enzymatic characterization. As these tools continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly play an indispensable role in unlocking the full potential of metabolic models for fundamental biological discovery and the development of next-generation cell factories.

In the realm of systems biology, the development of enzyme-constrained genome-scale metabolic models (ecGEMs) represents a significant advancement over traditional stoichiometric models. ecGEMs integrate catalytic constraints by incorporating enzyme turnover numbers (kcat values) and enzyme mass constraints, leading to more accurate predictions of cellular phenotypes [9]. The kcat value, or turnover number, is a fundamental kinetic parameter that defines the maximum number of substrate molecules an enzyme can convert to product per active site per unit time. This parameter is crucial for quantifying the catalytic capacity of enzymes and directly influences flux distributions in metabolic networks [9] [27]. Sourcing accurate, well-annotated kcat values from curated databases is therefore a critical step in constructing reliable ecGEMs. This protocol details methodologies for extracting these essential parameters from two primary resources: BRENDA and SABIO-RK.

Table 1: Key Kinetic Parameters for ecGEMs

| Parameter | Description | Role in ecGEMs |

|---|---|---|

| kcat | Turnover number (s⁻¹ or min⁻¹) | Determines maximum reaction rate per enzyme molecule |

| KM | Michaelis constant (mM) | Substrate concentration at half Vmax; indicates affinity |

| Ki | Inhibition constant (mM) | Measure of inhibitor potency |

| Vmax | Maximum reaction rate | Derived from kcat and enzyme concentration |

SABIO-RK: Biochemical Reaction Kinetics Database

SABIO-RK (System for the Analysis of Biochemical Pathways - Reaction Kinetics) is a web-accessible database that stores comprehensive, manually curated information about biochemical reactions and their kinetic properties [28] [29]. Its data model is reaction-oriented, providing a structured representation of quantitative information on reaction dynamics extracted from scientific literature [28] [30].

- Data Content and Curation: SABIO-RK contains kinetic parameters, related rate equations, kinetic law types, and the experimental conditions (e.g., pH, temperature, buffer) under which the data were determined [28]. The database also includes information on reaction participants, cellular location, and detailed enzyme information. All data is manually curated by biological experts, supported by automated consistency checks, ensuring a high degree of accurateness and completeness [28] [30]. As of 2017, it housed approximately 57,000 database entries extracted from over 5,600 publications [30].

- Organism Coverage: The database is not restricted to any particular organism class. It contains data for over 900 organisms, with a significant portion related to mammals (e.g., Homo sapiens, Rattus norvegicus) and model organisms like Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae [28] [30].

BRENDA: The Comprehensive Enzyme Information System

BRENDA (BRAunschweig ENzyme DAtabase) is one of the most comprehensive enzyme information resources, focusing on functional enzyme data [9]. While both databases contain kinetic parameters, their scopes and focuses differ.

- Comparative Focus: BRENDA is an enzyme-centric database, meaning its data is organized and accessible primarily by enzyme nomenclature (EC numbers) [30]. In contrast, SABIO-RK uses a reaction-oriented approach, which can be more intuitive for modelers building metabolic networks where reaction fluxes are the primary variables [28].

- Data Integration in ecGEM Tools: The practical utility of both databases is highlighted by their integration into modeling tools. For instance, the AutoPACMEN toolbox allows for the automated creation of enzyme-constrained models by automatically reading relevant enzymatic data, including kcat values, from both SABIO-RK and BRENDA [9].

Experimental Protocol: Sourcing kcat Values

Protocol 1: Querying SABIO-RK via the Web Interface