Evaluating Predictive Equations for Resting Energy Expenditure: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Clinical Professionals

This article provides a systematic evaluation of predictive equations for resting energy expenditure (REE), addressing critical needs in research and clinical practice.

Evaluating Predictive Equations for Resting Energy Expenditure: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Clinical Professionals

Abstract

This article provides a systematic evaluation of predictive equations for resting energy expenditure (REE), addressing critical needs in research and clinical practice. It examines the fundamental importance of REE assessment across diverse populations, from pediatric oncology to adult obesity. The content explores methodological approaches for equation development and application, identifies common challenges in equation selection across different patient demographics, and presents comparative validation studies. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this comprehensive review synthesizes current evidence to guide optimal equation selection while highlighting limitations and future directions for improving energy expenditure prediction in both research and clinical settings.

Understanding Resting Energy Expenditure: Fundamentals and Clinical Significance

Resting Energy Expenditure (REE) represents the minimum energy required to sustain vital physiological functions while at complete rest, typically accounting for 60-75% of total daily energy expenditure in individuals with sedentary lifestyles [1] [2]. REE is frequently used interchangeably with Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR), though it is distinct from Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR), which is measured under more stringent conditions including complete rest, thermoneutral environment, and after a 12-hour fast [1]. Accurate assessment of REE provides fundamental insights into human energy requirements and serves as a cornerstone for developing personalized nutritional interventions, especially in metabolic disorders, obesity management, and clinical care [1] [3].

The precise determination of REE has significant implications across multiple research and clinical domains. In nutritional epidemiology, REE values form the basis for calculating total energy requirements [4]. In metabolic research, deviations from expected REE values can indicate underlying pathological conditions, with hyperthyroidism potentially increasing REE by 50-100% and hypothyroidism decreasing it by 20-40% [1]. Furthermore, REE measurements provide critical benchmarks for evaluating therapeutic interventions aimed at modulating energy balance [2].

Measurement Techniques: From Gold Standard to Practical Alternatives

Indirect Calorimetry: The Reference Method

Indirect calorimetry stands as the gold standard technique for measuring REE in both research and clinical settings [3]. This method calculates energy expenditure through precise measurements of oxygen consumption (VO₂) and carbon dioxide production (VCO₂) using specialized metabolic analyzers [1] [5]. The procedure is grounded in the principle that energy production is proportional to gas exchange, with measurements typically conducted over 20-60 minutes after an overnight fast and period of rest [3].

The standard experimental protocol for indirect calorimetry requires strict adherence to several conditions to ensure accuracy:

- Timing and Fasting: Measurements should be performed in the morning after an 8-12 hour overnight fast [3]

- Rest Requirements: Participants must abstain from strenuous exercise for 24 hours prior and rest for 30 minutes before measurement [5]

- Environmental Controls: Testing occurs in a thermo-neutral environment with dim lighting and minimal distractions [1]

- Equipment Calibration: Regular two-point gas analyzer calibration and flow meter calibration are essential [5]

Two primary systems are employed for indirect calorimetry. The ventilated hood system allows participants to breathe comfortably under a transparent canopy while resting in a supine position, typically used for 30-60 minutes [1]. Alternatively, metabolic carts utilizing mouthpieces or face masks can measure gas exchange in various positions and during different activities [1]. The collected VO₂ and VCO₂ values are used to calculate REE using the Weir equation: REE = [3.94(VO₂) + 1.11(VCO₂)] × 1440, which provides energy expenditure in kcal/day [6] [3].

Key Research Reagents and Equipment

Table 1: Essential Research Materials for REE Measurement

| Item | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Indirect Calorimeter (e.g., Q-NRG+, Cosmed) | Measures VO₂ and VCO₂ | Gold standard REE measurement in clinical research [5] |

| Metabolic Cart | Analyzes inspired/expired gases | Laboratory-based energy expenditure measurement [1] |

| Ventilated Hood System | Captures respiratory gases | Comfortable REE measurement in supine position [1] |

| Bioelectrical Impedance Analyzer (e.g., Tanita BC-418) | Assesses body composition (FFM, FM) | Research on body composition-REE relationships [3] [2] |

| ActiGraph Accelerometer (wGT3X-BT) | Quantifies physical activity levels | Assessment of activity energy expenditure [5] |

| Calibration Gas Mixtures | Validates gas analyzer accuracy | Essential pre-measurement equipment calibration [3] |

Despite its accuracy, indirect calorimetry faces limitations in widespread application due to substantial equipment costs (typically thousands to tens of thousands of dollars), need for technical expertise, and significant time requirements per measurement [3]. These practical constraints have driven the development and use of predictive equations as accessible alternatives in both research and clinical practice [6].

Predictive Equations for REE: Comparative Analysis

Predictive equations estimate REE using anthropometric and demographic variables, offering practical advantages despite potential compromises in accuracy. These equations have been developed through regression analyses of large datasets, establishing mathematical relationships between easily measurable parameters and energy expenditure [1].

Major Predictive Equations and Their Formulations

Table 2: Commonly Used Predictive Equations for REE

| Equation | Year | Formula (Male) | Formula (Female) | Population Developed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harris-Benedict [1] | 1919 | 88.362 + (13.397 × W) + (4.799 × H) - (5.677 × A) | 447.593 + (9.247 × W) + (3.098 × H) - (4.330 × A) | 239 healthy individuals aged 16-63 years |

| Mifflin-St Jeor [1] [7] | 1990 | (10 × W) + (6.25 × H) - (5 × A) + 5 | (10 × W) + (6.25 × H) - (5 × A) - 161 | 498 healthy individuals (normal weight, overweight, obese) |

| FAO/WHO/UNU (Weight only) [6] | 1985 | (11.6 × W) + 879 | (8.7 × W) + 829 | Large international population |

| FAO/WHO/UNU (Weight & Height) [6] | 1985 | (11.3 × W) + (16 × H) + 901 | (8.7 × W) - (25 × H) + 865 | Large international population |

| Owen [6] | 1986/1987 | 879 + (10.2 × W) | 795 + (7.18 × W) | 104 men and 44 women with wide weight range |

W = weight (kg), H = height (cm), A = age (years), H (m) = height in meters for WHO2 equation

Experimental Comparisons of Predictive Equations

Numerous studies have systematically evaluated the performance of predictive equations against indirect calorimetry across diverse populations. The following experimental data illustrate the comparative accuracy of these equations:

Table 3: Experimental Comparison of REE Predictive Equations vs. Indirect Calorimetry

| Study Population | Sample Size | Best Performing Equation(s) | Accuracy Rate | Mean Bias | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overweight/Obese Adults | 82 | Harris-Benedict, WHO1, WHO2 | High intraclass correlation | Low systematic error | [6] |

| Hospitalized Patients | 60 | Harris-Benedict, Mifflin-St Jeor | Within 10% for groups | Wide individual limits of agreement | [8] |

| NAFLD & T2DM Adults | 88 | FAO/WHO/UNU (Weight) | 46.5% | +10.2 kcal/day | [3] |

| Severely Obese Children/Adolescents | 287 | Lazzer-Sartorio | 55% | +1.6% (NS) | [9] |

| Overweight Adults (6-month intervention) | 33 | Owen | Most comparable | Not significant | [2] |

A 2008 study comparing Harris-Benedict and Mifflin-St Jeor equations in 60 hospitalized patients found that while both equations showed no statistically significant differences from measured REE at the group level, they demonstrated wide limits of agreement at the individual level, suggesting clinically important differences would be obtained when applying these equations to individual patients [8].

For specialized populations, equation performance varies significantly. In patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and type 2 diabetes mellitus, the FAO/WHO/UNU (weight only) equation demonstrated the smallest average bias (10.2 kcal/day) and highest accuracy (46.5%), though notably less than half of participants had REE estimates within 10% of measured values [3]. Similarly, in severely obese Caucasian children and adolescents, the Lazzer-Sartorio equations showed superior agreement with measured REE, with higher accuracy (55% of subjects) and lower mean differences compared to seven other equations [9].

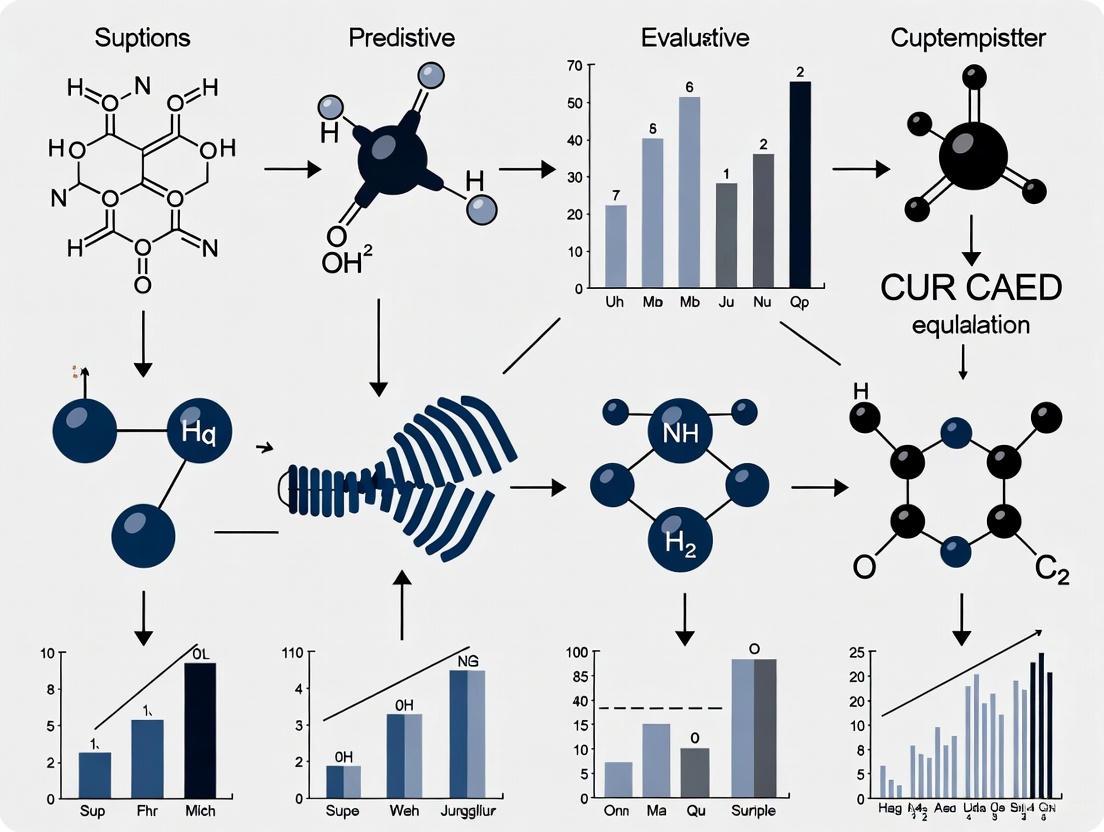

Diagram 1: Decision Framework for REE Assessment Method Selection. The flowchart illustrates the process of selecting appropriate REE measurement or estimation methods based on available resources and population characteristics, culminating in individualized nutrition planning.

Factors Influencing Resting Energy Expenditure

Biological Determinants

Multiple biological factors significantly impact REE, accounting for substantial interindividual variability:

Body Composition: Fat-free mass (FFM) represents the most significant determinant of REE, accounting for approximately 60-70% of its variance [5]. Muscle tissue is metabolically more active than adipose tissue, with each pound of muscle burning approximately 6 kcal/day at rest compared to 2 kcal/day for fat tissue [1]. A 2025 cross-sectional study confirmed FFM as the strongest predictor of REE, along with related metrics including total body water, body cell mass, and muscle mass [5].

Age: REE typically declines by 1-2% per decade after age 20, primarily due to age-related changes in body composition including reduced lean body mass and decreased cellular metabolism [1]. This decline occurs later in women (approximately age 50) compared to men (approximately age 40) [4].

Sex: Men generally exhibit 10-15% higher REE than women of similar age and weight, primarily attributable to differences in body composition, particularly greater lean body mass [1]. Even after adjusting for body composition differences, women typically show lower REE values [4].

Hormonal Factors: Thyroid hormones (T3 and T4) and catecholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine) significantly increase REE [1]. Additionally, recent research indicates insulin levels and HOMA-IR show positive associations with REE, though these relationships may be mediated by body composition factors [5].

Environmental and Lifestyle Influences

Physical Activity: All physical activity intensities demonstrate significant associations with REE, with moderate physical activity (MPA) maintaining significance even after adjusting for sex and FFM [5]. This relationship may be attributed to habitual spontaneous physical activity generating post-exercise metabolic elevation and promoting adipose tissue browning [5].

Nutritional Status: Prolonged fasting or severe caloric restriction can reduce REE by 20-30% as an adaptive energy conservation mechanism [1]. Similarly, severe caloric restriction (50% of energy requirements) can decrease REE by 10-15% within 2-4 weeks [1].

Environmental Factors: Ambient temperature significantly impacts REE, with a 1°C decrease potentially increasing REE by 5-7% through adaptive thermogenic responses [1]. High altitude exposure (above 4,000 meters) can elevate REE by 10-20% due to hypoxic adaptive responses [1].

Advanced Research Applications and Methodological Considerations

Total Daily Energy Expenditure Estimation

In research settings, REE values typically serve as the foundation for estimating total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) through multiplication by appropriate physical activity level (PAL) factors:

- Sedentary: TDEE = REE × 1.2 [1]

- Lightly active: TDEE = REE × 1.375 [1] [7]

- Moderately active: TDEE = REE × 1.55 [1] [7]

- Active: TDEE = REE × 1.725 [1] [7]

- Very active: TDEE = REE × 1.9 [7]

This multiplicative approach enables researchers to translate laboratory REE measurements into real-world energy requirements for nutritional planning and intervention design [2].

Methodological Considerations for Research

When designing studies involving REE assessment, several methodological considerations are essential:

Measurement Conditions: Standardization is critical, requiring strict adherence to fasting protocols, rest periods, and environmental controls to ensure data comparability [3]. Even minor deviations in protocol implementation can significantly impact results.

Equipment Selection: Different indirect calorimetry systems (ventilated hood vs. metabolic cart) offer distinct advantages and limitations depending on research objectives, participant characteristics, and measurement context [1].

Population-Specific Validation: Researchers should validate chosen predictive equations against indirect calorimetry in their specific study populations when possible, particularly when investigating groups with distinctive metabolic characteristics [6] [9].

Longitudinal Assessment: In intervention studies, serial REE measurements are recommended as REE typically decreases with weight loss due to adaptive thermogenesis and loss of lean body mass, necessitating adjustment of energy prescription protocols [2].

Resting Energy Expenditure represents a fundamental parameter in nutritional science and metabolic research, with accurate assessment crucial for both research and clinical applications. While indirect calorimetry remains the gold standard for precise REE measurement, practical constraints often necessitate the use of predictive equations. The comparative performance of these equations varies significantly across different populations, with the Mifflin-St Jeor equation generally recommended for overweight and obese adults, the FAO/WHO/UNU equations for international populations, and the Harris-Benedict equation for general adult populations [1] [6] [7].

For researchers and clinicians, selection of appropriate assessment methods must balance accuracy requirements with practical constraints, while considering population-specific characteristics. Future research directions should focus on developing and validating more precise population-specific equations, particularly for understudied groups with distinct metabolic profiles. Additionally, advancing accessible indirect calorimetry technologies could bridge the current gap between precision and practicality in REE assessment, ultimately enhancing the quality of both research outcomes and clinical nutritional interventions.

Resting energy expenditure (REE) represents the number of calories required to maintain basic physiological functions at rest. Accurate REE measurement is crucial for research in metabolism, nutrition, and drug development. While various predictive equations offer convenient estimates, indirect calorimetry (IC) stands as the recognized gold standard for direct REE measurement in clinical and research settings [10] [11]. This guide objectively examines the principles, performance, and limitations of IC compared to predictive equations, providing researchers with a critical framework for selecting appropriate methodologies.

Principles of Indirect Calorimetry

Indirect calorimetry determines energy expenditure by measuring the body's gas exchange. The fundamental principle is based on the knowledge that heat production can be accurately estimated from oxygen consumption (VO₂) and carbon dioxide production (VCO₂) [12] [11].

Theoretical Foundations

The methodology rests on several key assumptions [11] [13]:

- All oxygen consumed is used to oxidize degradable fuels (carbohydrates, fats, proteins)

- All carbon dioxide produced is recovered and measured

- The oxidation of different macronutrients has fixed ratios of O₂ consumed to CO₂ produced

- Substrate loss through routes like feces and urine is negligible

Key Calculations

The core measurements obtained are VO₂ and VCO₂, which allow calculation of:

- Respiratory Quotient (RQ): The ratio of VCO₂ to VO₂ (VCO₂/VO₂), which indicates the predominant metabolic substrate being oxidized [12]

- Resting Energy Expenditure (REE): Typically calculated using the Weir equation [11] [13]: REE (kcal/day) = [3.941 × VO₂ (L/min) + 1.106 × VCO₂ (L/min)] × 1440

Table 1: Respiratory Quotient Values for Different Metabolic Substrates

| Metabolic Substrate | Respiratory Quotient (RQ) |

|---|---|

| Carbohydrates | 1.00 |

| Proteins | 0.80-0.82 |

| Fats | 0.70 |

| Mixed Diet | 0.85 |

Experimental Validation: IC vs. Predictive Equations

Multiple studies have quantitatively compared the accuracy of IC against commonly used predictive equations across diverse patient populations.

Performance in Critical Care Settings

A large retrospective validation study with 3,573 REE measurements in 1,440 ICU patients demonstrated the superior accuracy of IC [14]. The performance of predictive equations was notably limited:

Table 2: Performance of Predictive Equations in ICU Patients (n=1,440)

| Predictive Equation | Mean Difference from IC | Correlation with IC | Agreement with IC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Faisy | 90 kcal | Not specified | Not specified |

| Harris-Benedict | Not specified | 52% | 50% |

| Jolliet | Not specified | Not specified | 62% concordance |

The study concluded that predictive equations demonstrated low performance compared to IC, with agreement within 10% of actual caloric needs achieved in only one-third of patients [14].

Specialized Patient Populations

Trauma Patients

A pilot study of 31 trauma ICU patients revealed significant discrepancies between IC and predictive equations [15]:

Table 3: REE Measurements in Trauma Patients (n=31)

| Measurement Method | REE (kcal/day, Mean ± SD) | Significant Difference from IC |

|---|---|---|

| Indirect Calorimetry | 2,146 ± 444 | Reference |

| Ireton-Jones Equation | 2,279 ± 202 | No (p=0.053) |

| Harris-Benedict Equation | 1,509 ± 205 | Yes (p=0.006) |

| Fleisch Equation | 1,509 ± 154 | Yes (p=0.003) |

| Robertson & Reid Equation | 1,443 ± 160 | Yes (p<0.001) |

The Ireton-Jones equation showed the highest correlation with IC (r=0.521), while other equations significantly underestimated energy requirements [15].

Renal Transplantation Patients

A study of 51 renal transplant patients found that most predictive equations significantly underestimated REE compared to IC [16]. The Cunningham equation showed the closest agreement with a mean difference of -69 kcal, while the Bernstein equation substantially underestimated REE by -478 kcal. The study developed a new population-specific equation based on fat-free mass: REE = 424.2 + 24.7 × FFM (kg) [16].

Experimental Protocols for IC Measurement

Standardized protocols are essential for obtaining accurate IC measurements. The following methodologies are derived from cited experimental approaches.

Protocol for Mechanically Ventilated Patients

Based on trauma ICU studies [15]:

- Patient Preparation: Patients should be sedated to a Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) of -2 and maintained in steady state for 15 minutes before measurement

- Ventilator Settings: Fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO₂) should be below 60% with stable ventilator parameters

- Measurement Device: Use a calibrated metabolic cart (e.g., CCM Express, MGC Diagnostics)

- Measurement Duration: Continue until a steady state is achieved (typically 15-30 minutes after equilibration)

- Exclusion Criteria: FiO₂ > 0.6, respiratory quotient outside physiological range (0.67-1.3)

Protocol for Spontaneously Breathing Subjects

For non-ventilated subjects, different gas collection systems are employed [12] [11]:

- Douglas Bag: Collects all expired air in an inflatable airtight bag for subsequent volume and composition analysis

- Canopy System: Subject's head is placed under a transparent hood connected to a pump with adjustable ventilation

- Face Mask: Breath-by-breath measurement using a mask connected to a turbine flowmeter

Diagram 1: Indirect Calorimetry Measurement Workflow

Technological Approaches and Systems

Various IC systems have been developed, each with specific advantages and limitations [11] [13]:

Table 4: Indirect Calorimetry System Classifications

| System Type | Operating Principle | Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Closed-circuit | Measures O₂ consumption in a closed space with CO₂ absorbers | High FiO₂ requirements | Equipment size, poor portability |

| Open-circuit | Subject breathes room air, expired gas analyzed | Most common clinical approach | Limited accuracy with FiO₂ > 0.8 |

| Douglas Bag | Total collection of expired gas in a bag | Research settings, reference standard | Collection bag size, potential leaks |

| Canopy/Dilution | Head under transparent hood, measures gas dilution | Clinical nutrition, resting measurements | Requires patient cooperation |

Limitations and Technical Challenges

Despite its gold standard status, IC has several important limitations that researchers must consider:

Clinical Limitations

- High FiO₂ Requirements: Standard open-circuit systems lose accuracy when FiO₂ exceeds 0.8 due to mathematical limitations in the Haldane transformation [11] [13]

- Circuit Leaks: Any leaks in the ventilator circuit or measurement apparatus can falsely reduce measured VO₂ and VCO₂ [11]

- Specific Patient Populations: Challenges exist with patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) or continuous renal replacement therapy due to unmeasured CO₂ loss [17]

Practical Limitations

- Equipment Cost: Commercial IC systems represent significant financial investment

- Technical Expertise Required: Proper operation requires trained personnel for calibration and measurement [10]

- Time-Consuming: Measurements typically require 20-60 minutes of stable conditions per subject

Diagram 2: Limitations of Indirect Calorimetry

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment

Table 5: Key Research Materials for Indirect Calorimetry Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Cart | Measures O₂ consumption and CO₂ production to calculate REE | CCM Express (MGC Diagnostics), Vmax Spectra |

| Calibration Gases | Ensure accuracy of gas analyzers through regular calibration | Precision gas mixtures with known O₂ and CO₂ concentrations |

| Douglas Bag Systems | Gold standard for gas collection in spontaneously breathing subjects | Airtight bags with appropriate volume capacity |

| Ventilator Interface | Allows IC measurement in mechanically ventilated patients | Compatible with ICU ventilators |

| Gas Analyzers | Measure O₂ and CO₂ concentrations in inspired and expired air | Paramagnetic O₂ sensors, infrared CO₂ analyzers |

| Flow Meters | Measure volume of inspired and/or expired air | Pneumotachographs, ultrasonic flow meters |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Recent technological advances have expanded IC applications beyond basic REE measurement:

Isotopic Calorimetry

The integration of ¹³CO₂ sensors with conventional IC systems enables quantification of exogenous versus endogenous substrate oxidation, providing insights into specific metabolic pathways [18]. This approach allows researchers to track the oxidation of individually labeled substrates such as glucose or fatty acids in real-time.

Extended Critical Care Applications

Modified IC protocols have been developed for challenging clinical scenarios, including patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) [17]. These approaches combine conventional IC measurements with mathematical modeling of O₂ and CO₂ content pre- and post-membrane oxygenation.

Indirect calorimetry remains the undisputed gold standard for REE measurement in research settings, providing accuracy that predictive equations cannot reliably match across diverse populations. While technical limitations exist, standardized protocols and proper equipment selection can mitigate many challenges. For research requiring precise energy expenditure data, particularly in metabolic studies or drug development, IC provides invaluable data that justifies the operational complexities. The continued refinement of IC technology and methodologies promises to further expand its applications in understanding human metabolism.

Resting Energy Expenditure (REE) represents the amount of energy required by the body to maintain fundamental physiological functions while at rest. As the largest component of total daily energy expenditure (accounting for 60-75%), accurately determining REE is fundamental to nutritional planning across clinical populations [19]. In clinical practice, indirect calorimetry (IC) serves as the gold standard for REE measurement through direct measurement of oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production [3]. However, due to the high cost, limited availability, and technical expertise required for IC, healthcare providers frequently rely on predictive equations to estimate energy requirements using easily accessible variables such as age, sex, weight, and height [20] [21].

The miscalculation of REE presents substantial risks in clinical settings. When predictive equations underestimate true energy needs, patients face the threat of inadvertent underfeeding, potentially leading to hospital-acquired malnutrition and its associated complications. Conversely, overestimation of REE may result in overfeeding, contributing to excessive weight gain, metabolic disturbances, and increased complications in obese populations [22] [23]. This comparative guide examines the clinical consequences of REE miscalculation across different patient populations, evaluates the performance of various predictive equations against measured energy expenditure, and provides evidence-based recommendations for optimizing nutritional support in research and clinical practice.

Performance Comparison of REE Predictive Equations Across Clinical Populations

The accuracy of REE predictive equations varies significantly across different patient populations and clinical conditions. The tables below summarize comparative performance data from recent studies investigating equation accuracy in specific populations.

Table 1: Performance of REE Predictive Equations in Pediatric Oncology Patients (n=203) [20]

| Equation | Average Bias (kcal/day) | 95% Confidence Interval | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| INP-Simple (New) | 114.8 | -408 to 638 | Least bias in this population |

| INP-Morpho (New) | 114.8 | -408 to 638 | Includes body composition parameters |

| Molnár | -82.3 | -741.3 to 576.7 | Moderate performance |

| Harris-Benedict | -133.6 | -671.5 to 404.2 | Underestimates REE |

| Oxford | -110.6 | -661.4 to 440.1 | Underestimates REE |

| Schofield | -185.4 | -697.6 to 326.8 | Significant underestimation |

| FAO/WHO/UNU | -178.8 | -683.9 to 326.3 | Significant underestimation |

| IOM | -201.0 | -761.7 to 359.7 | Greatest underestimation |

Table 2: Equation Performance in Morbidly Obese Patients (n=4,247) [23]

| Equation | Accuracy Rate | Average Bias (kcal/day) | Performance in Comorbidities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mifflin-St Jeor | 61.1% | -89.87 | Best performance in patients with ≥3 comorbidities |

| Mifflin-St Jeor | 69% | -19.17 | Best in patients with type 2 diabetes |

| Mifflin-St Jeor | 66% | -21.67 | Best in patients with sleep apnea |

| Harris-Benedict | 45.3% | -152.4 | Consistent underestimation |

| WHO/FAO/ONU | 51.2% | -135.8 | Moderate underestimation |

| Müller | 48.7% | -141.9 | Moderate underestimation |

Table 3: Equation Accuracy in NAFLD and T2DM Patients (n=88) [3]

| Equation | Average Bias (kcal/day) | 95% Limits of Agreement | Accuracy Rate (% within ±10% of IC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FAO/WHO/UNU (weight) | +10.2 | -57.4 to 78.0 | 46.5% |

| Müller (FFM) | -45.8 | -125.3 to 33.7 | 42.1% |

| Harris-Benedict | -65.3 | -144.8 to 14.2 | 38.6% |

| Mifflin-St Jeor | -88.7 | -168.2 to -9.2 | 35.2% |

| Owen | -155.4 | -234.9 to -75.9 | 28.4% |

| Thumb (25 × weight) | -402.2 | -477.3 to -327.1 | 20.4% |

Clinical Consequences of REE Miscalculation

Impact on Malnutrition and Treatment Outcomes

The inaccurate estimation of energy requirements directly impacts the development and progression of disease-related malnutrition. In hospitalized patients, malnutrition prevalence ranges from 13-40%, with many patients experiencing further nutritional decline during admission [22]. The consequences of REE miscalculation are particularly pronounced in pediatric oncology, where malnutrition at diagnosis ranges from 7% in leukemia patients to 50% in those with neuroblastoma [20].

In clinical practice, REE underestimation can lead to inadequate nutrition support, contributing to cascading physiological impairments. Malnourished patients demonstrate:

- Muscle function decline: Reduced energy-dependent cellular membrane pumping occurs even before measurable changes in muscle mass [22]

- Immune dysfunction: Impaired cell-mediated immunity and phagocyte function increase infection risk [22]

- Poor wound healing: Particularly problematic in surgical patients, leading to extended recovery [22]

- Increased complications: Malnourished surgical patients experience 3-4 times higher complication and mortality rates compared to well-nourished counterparts [22]

The economic impact is substantial, with disease-related malnutrition costs in the UK alone exceeding £13 billion annually—surpassing even obesity-related costs [22]. Even modest improvements in nutritional assessment could yield significant savings while improving patient outcomes.

Consequences in Obesity and Metabolic Disorders

In obese populations, accurate REE prediction becomes particularly challenging due to alterations in body composition and metabolic heterogeneity. The Mifflin-St Jeor equation demonstrates the best performance in morbidly obese patients, especially those with multiple comorbidities [23]. However, even this equation shows significant limitations, with accuracy rates of only 61.1% in patients with three or more comorbid conditions [23].

In patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and type 2 diabetes, predictive equations show particularly poor performance, with no equation achieving >50% accuracy at the individual level [3]. The commonly used "Thumb rule" (25 kcal/kg) demonstrates the worst performance, with a substantial average bias of -402.2 kcal/day and only 20.4% accuracy [3]. This systematic underestimation may lead to excessive calorie restriction, potentially exacerbating muscle loss while preserving fat mass during weight loss interventions.

Special Considerations in Critical Illness and Elderly Populations

In ventilated critically ill children, a comprehensive evaluation of 15 predictive equations revealed that none met performance criteria across the REE spectrum of 200-1000 kcal/day [24]. Even the best-performing equations (Mehta, Schofield, Henry, and Talbot) demonstrated wide confidence intervals, creating significant risks of underfeeding or overfeeding, particularly in the youngest patients [24].

Elderly patients present unique challenges due to age-related changes in body composition and the high prevalence of malnutrition (affecting up to 60% of hospitalized elderly) [19]. A systematic review identified 210 different predictive equations used in elderly populations, with significant heterogeneity in their estimates [19]. Equations incorporating only body weight demonstrated the highest agreement, while more complex formulas showed wider variation, potentially impacting clinical outcomes in this vulnerable population.

Methodological Approaches for REE Assessment

Gold Standard Protocol: Indirect Calorimetry

Indirect calorimetry represents the reference method for REE measurement through measurement of oxygen consumption (VO₂) and carbon dioxide production (VCO₂) [3]. The standard experimental protocol includes:

- Measurement conditions: Participants are measured in the morning after an 8-12 hour overnight fast, while lying supine in a thermoneutral environment, awake and motionless [3]

- Equipment calibration: Period gas and flow calibration are performed before each measurement using certified reference gases [3]

- Measurement duration: Typically 20 minutes of continuous measurement, discarding the first 5 minutes to allow for equipment stabilization [3]

- Data analysis: VO₂ and VCO₂ are converted to REE using the Weir equation: REE = [3.94(VO₂) + 1.11(VCO₂)] × 1,440 [3]

- Pre-test instructions: Participants abstain from caffeine, tobacco, and moderate-to-high intensity physical activity for 24 hours prior to testing [3]

Development of Population-Specific Predictive Equations

The development of new predictive equations follows standardized methodological approaches:

- Study design: Cross-sectional studies measuring REE via IC while collecting anthropometric and body composition data [20] [21]

- Participant recruitment: Population-specific recruitment based on demographic characteristics, health status, and clinical diagnoses [20]

- Statistical analysis: Multiple regression analyses to identify relationships between REE and predictor variables (weight, height, age, sex, body composition) [20] [21]

- Validation: Splitting cohorts into development and validation groups or external validation in independent populations [25]

- Performance assessment: Evaluating bias (average difference between measured and predicted REE) and accuracy (percentage of estimates within ±10% of measured REE) [20]

Recent advances incorporate bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) parameters, with equations including raw BIA variables (bioimpedance index and phase angle) showing slightly improved individual accuracy (70.3% in men, 72.3% in women) compared to traditional equations [25].

Metabolic Pathways and Clinical Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the metabolic consequences and clinical decision pathways involved in REE miscalculation.

Diagram 1: Metabolic and clinical consequences of REE miscalculation, showing how inaccurate estimation leads to adverse patient outcomes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for REE Investigation

| Tool/Reagent | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Cart (e.g., QUARK RMR, COSMED) | Measures VO₂ and VCO₂ for IC | Requires regular gas and flow calibration; specialized operation needed [3] |

| Bioelectrical Impedance Analyzer (e.g., Tanita BC-418, SECA) | Assesses body composition (FFM, FM) | Provides raw BIA variables (phase angle) for enhanced equations [25] |

| Digital Calibrated Scale (e.g., SECA 813) | Precise weight measurement | Essential for accurate anthropometric input data [20] |

| Ultrasonic Stadiometer (e.g., InLab S50) | Accurate height measurement | Critical for BMI calculation and equation inputs [20] |

| Calibrated Skinfold Calipers | Adipose tissue thickness measurement | Alternative body composition assessment when BIA unavailable |

| Data Collection Software | Standardized data management | Customized platforms for integrating IC, BIA, and anthropometric data |

The consistent miscalculation of resting energy expenditure presents significant clinical risks across diverse patient populations. Current evidence demonstrates that general predictive equations frequently misestimate true energy requirements, with potentially serious consequences for nutritional status, treatment outcomes, and healthcare costs. The development of population-specific equations, such as the INP equations for pediatric oncology patients, shows promise for improving accuracy in specialized clinical contexts [20].

For researchers and clinicians, several key recommendations emerge from this analysis:

Prioritize indirect calorimetry in complex patients, particularly those with multiple comorbidities, metabolic disorders, or critical illness where predictive equations demonstrate poor accuracy [24] [3] [23]

Select population-appropriate equations when IC is unavailable, recognizing that even the best-performing equations may misestimate individual requirements by several hundred kilocalories per day [20] [23]

Incorporate body composition data where possible, as equations including fat-free mass and BIA parameters generally demonstrate improved accuracy compared to those based solely on weight and height [25]

Implement regular monitoring of nutritional status and weight changes to identify miscalculation early and adjust nutritional support accordingly

Future research should focus on developing more sophisticated prediction models that incorporate metabolic biomarkers, genetic factors, and advanced body composition analysis to better capture the complex determinants of energy expenditure in health and disease.

Comparative Accuracy of Predictive Equations Across Populations

The accuracy of predictive equations for Resting Energy Expenditure (REE) varies significantly across different patient populations. The tables below summarize the performance of various equations in pediatric oncology, general pediatric obesity, and adult oncology patients.

Table 1: Performance of REE Predictive Equations in Pediatric Oncology Patients (2025 Study) [26] [20] [27]

| Equation Name | Bias (kcal/day) | 95% Limits of Agreement (kcal/day) | Clinical Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| INP-Simple/Morpho (New) | 114.8 | -408 to 638 | Preferred; least bias in this population |

| Molnár | -82.3 | -741 to 577 | Acceptable performance |

| Oxford | -110.6 | -661 to 440 | Moderate bias |

| Harris-Benedict | -133.6 | -672 to 404 | Significant bias |

| Kaneko | -135.6 | -653 to 381 | Significant bias |

| Müller | -162.6 | -715 to 390 | Significant bias |

| FAO | -178.8 | -684 to 326 | Significant bias |

| Schofield | -185.4 | -698 to 327 | Significant bias |

| IOM | -201.0 | -762 to 360 | Greatest bias |

Table 2: Performance of REE Predictive Equations in Obese Pediatric and Adult Populations [28] [9] [29]

| Patient Population | Most Accurate Equation(s) | Accuracy Rate | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obese Children/Adolescents | Lazzer-Sartorio | 55% accurate | Showed the best agreement with measured REE in severely obese Caucasians. [9] |

| Obese Children | Derumeaux-Burel (New) | No significant difference vs. measured | Specifically developed for a large population of obese children; validated externally. [29] |

| Obese Children | FAO/WHO/UNU | No significant mean difference, but low accuracy (26%) | Low individual accuracy despite good mean performance. [9] |

| Obese Adults (BMI ≥30) | Harris-Benedict (1918) | Best for obese subgroup | Recommended for obese hospital patients when indirect calorimetry is not available. [28] |

Table 3: Performance of REE Predictive Equations in Adult Oncology Patients [30]

| Aspect of Accuracy | Key Finding | Implication for Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Accuracy | REE cannot be accurately predicted on an individual level. | Highlights the limitation of all predictive equations in oncology. |

| Best Performing | Mifflin-St. Jeor had the smallest limits of agreement (-21.7% to 11.3%). | Most precise, but individual-level inaccuracy remains. |

| Body Composition | Equations including Fat-Free Mass (FFM) were not consistently more accurate. | Simpler equations may be as useful as complex ones. |

| Bias Correlation | Bias was consistently positively correlated with age and negatively with Fat Mass (FM). | Patient age and body composition significantly impact equation error. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Development of INP Predictive Equations in Pediatric Oncology

A 2025 cross-sectional study established a specific protocol for developing and validating REE equations in pediatric oncology patients. [20] [27]

- Patient Population: The study recruited 226 treatment-naïve pediatric patients (6 to <18 years) with a recent oncological diagnosis (0-2 weeks post-diagnosis). The final analysis included 203 participants, with the majority having solid tumors (68.5%), followed by leukemia (20.2%) and brain tumors (11.3%). [26] [20] [27]

- Exclusion Criteria: Patients were excluded if they were taking medications affecting metabolic function (e.g., corticosteroids, thyroid hormones, insulin), had diagnoses of hypothyroidism/hyperthyroidism, or had severe cognitive/motor impairments. [20] [27]

- Anthropometric & Nutritional Assessment: Weight was measured using a calibrated digital scale (SECA 813), and height was measured with an ultrasonic stadiometer (InLab S50). Various circumferences (waist, hip, mid-upper arm, etc.) were measured. Nutritional status was classified using WHO BMI-for-age and height-for-age z-scores via AnthroPlus software. [20] [27]

- Body Composition Analysis: Determined using bioelectrical impedance analysis, providing data on fat-free mass and fat mass for the INP-Morpho equation. [26] [20]

- REE Measurement (Gold Standard): REE was measured using Indirect Calorimetry (IC) with a standardized protocol, following a fasting period. [26] [20]

- Equation Development and Comparison: Two new equations (INP-simple with basic clinical variables; INP-Morpho with body composition) were developed using statistical modeling. Their accuracy was compared against measured IC values and existing equations (e.g., Harris-Benedict, Schofield) using bias, limits of agreement, and confidence intervals. [26] [20] [27]

Protocol: Validation of Equations in Obese Pediatric Populations

A 2007 study established a protocol for comparing predictive equations in obese youth. [9]

- Patient Population: 287 severely obese Caucasian children and adolescents (121 males, 166 females) with a mean BMI z-score of 3.3. [9]

- Body Composition Analysis: Assessed using bioelectrical impedance analysis. [9]

- REE Measurement: REE was measured by indirect calorimetry (MREE). [9]

- Equation Comparison: REE was calculated using multiple predictive equations (McDuffie, Derumeaux, Tverskaya, Schofield, FAO/WHO/UNU, Harris-Benedict, Lazzer-Sartorio). The agreement between predicted (PREE) and measured (MREE) values was analyzed using mean differences, standard deviations, and the percentage of subjects for whom the prediction was accurate (likely within 10% of MREE). [9]

Research Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for developing and validating a population-specific REE predictive equation, as demonstrated in the 2025 pediatric oncology study. [26] [20] [27]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Equipment and Materials for REE Research [20] [27] [31]

| Item | Specific Example(s) | Critical Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Indirect Calorimeter | Metabolic cart (e.g., Deltatrac 2 MBM-200, Vmax Encore n29); Hand-held device (e.g., MedGem) | Gold-standard instrument for directly measuring REE by analyzing oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production. [20] [31] [28] |

| Calibration Gases | Reference gas mixture (e.g., 95% O2, 5% CO2); Two standard gases (e.g., 26% O2, 0% CO2 and 16% O2, 4% CO2) | Ensures the accuracy and precision of the indirect calorimeter before and during measurements. [28] |

| Calibrated Digital Scale | SECA Alpha, SECA 813 | Precisely measures patient body weight, a key variable in most predictive equations. [20] [27] [28] |

| Stadiometer | Ultrasonic stadiometer (e.g., InLab S50) | Accurately measures patient height, a key variable in many predictive equations and for BMI calculation. [20] [27] |

| Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA) | Various bioimpedance analyzers | Assesses body composition (fat-free mass, fat mass), which is used in advanced predictive equations and body composition-specific validation. [26] [20] [9] |

| Anthropometric Tape | SECA 201 | Measures body circumferences (mid-upper arm, waist, etc.) for nutritional assessment. [20] [27] |

Resting energy expenditure (REE) represents the energy required to maintain fundamental physiological functions at rest. This comprehensive analysis examines the metabolic foundations of REE and its intricate relationships with body composition and physiological status. We evaluate predictive equations against indirect calorimetry as the reference standard, presenting quantitative comparisons for researchers and drug development professionals. The evidence demonstrates that lean body mass serves as the primary determinant of RMR, accounting for 60-75% of total daily energy expenditure. This review synthesizes current methodologies, validation protocols, and technical resources to advance research in metabolic monitoring and predictive modeling of energy expenditure.

Basal metabolic rate (BMR), often used interchangeably with REE in clinical literature, is defined as the rate of metabolism that occurs when an individual is at rest in a warm environment and in the post-absorptive state, having not eaten for at least 12 hours [32]. This energy supports the function of vital organs including the heart, lungs, nervous system, and kidneys [32]. REE represents the largest component (~60-75%) of total daily energy expenditure in adults [33], reflecting the steady-state level of energy homeostasis in the body. The accurate assessment of REE is fundamental to research in obesity, metabolic disorders, and nutritional interventions, with predictive equations serving as essential tools when direct calorimetric measurement is impractical.

The complex interplay between body composition, physiological status, and metabolic rate forms a critical foundation for understanding human energy expenditure. Research has consistently demonstrated that body composition parameters—specifically the proportions of fat mass and fat-free mass—exert profound influences on metabolic rate [34] [35]. These relationships are further modulated by factors including age, sex, nutritional status, and physiological conditions such as pregnancy, disease states, and aging [36]. This review systematically evaluates the metabolic basis of REE within the context of contemporary research methodologies and predictive modeling approaches.

The Metabolic Basis of REE

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

Resting energy expenditure represents the energy required to maintain cellular, tissue, and organ system homeostasis under basal conditions. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition defines BMR as the "minimum number of calories your body needs to perform basic bodily functions" [34]. These functions include respiratory circulation, neural function, protein synthesis, and ion transport across membranes—processes that continue uninterrupted during waking and sleep states. While the terms REE and BMR are often used interchangeably in clinical practice, BMR typically refers to measurements made under more strictly controlled conditions (complete rest, thermoneutral environment, and post-absorptive state), whereas REE may allow for less restrictive conditions while still capturing the dominant component of daily energy expenditure.

From a biochemical perspective, REE represents the sum of all energy-releasing reactions occurring at rest, primarily through mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. The metabolic processes contributing to REE include substrate cycling, cardiac muscle contraction, respiratory muscle work, renal solute transport, and hepatic protein synthesis. The brain alone accounts for approximately 20% of REE despite representing only 2% of body mass, highlighting the variable metabolic activity of different tissues [32].

Body Composition as a Determinant of REE

Body composition exhibits a fundamental hierarchical organization that directly informs our understanding of its relationship with REE. The five-level model of body composition—spanning atomic, molecular, cellular, tissue-organ, and whole-body levels—provides a framework for understanding metabolic variability between individuals [35].

Figure 1: Hierarchical model of body composition and its relationship to REE. The molecular level components (Fat-Free Mass and Fat Mass) most directly determine REE. FFM: Fat-Free Mass; FM: Fat Mass; ECF: Extracellular Fluid; ECS: Extracellular Solids.

At the molecular level, the body can be partitioned into fat mass (FM) and fat-free mass (FFM), with FFM comprising approximately 73% water, 20% protein, and 7% mineral [35]. This distinction is metabolically significant because FFM represents the metabolically active tissue component, with different organs contributing disproportionately to REE relative to their mass. Research indicates that the high metabolic activity of organs like the heart, kidneys, and liver contrasts with the relatively low metabolic rate of adipose tissue, explaining why individuals with higher FFM typically exhibit higher REE [34].

The relationship between lean body mass and REE forms a fundamental principle in energy metabolism. Studies consistently demonstrate that "the more Lean Body Mass you have, the greater your Basal Metabolic Rate will be" [34]. This occurs because muscle tissue and organs require energy for maintenance even at complete rest, unlike adipose tissue which is relatively metabolically inactive. This understanding reframes the concept of a "slow metabolism" from one of velocity to one of capacity—individuals with greater lean mass possess a "bigger" metabolism with higher absolute energy requirements [34].

Predictive Equations for REE: Comparative Analysis

Reference Standard: Indirect Calorimetry

Indirect calorimetry (IC) represents the gold standard for measuring REE in clinical and research settings. This noninvasive method calculates energy expenditure from respiratory gas exchange—specifically oxygen consumption (VO₂) and carbon dioxide production (VCO₂)—using the Weir equation: REE = [3.94(VO₂) + 1.11(VCO₂)] × 1440 min/day [6]. The methodology requires strict standardization, including measurements performed in the morning after a 12-hour fast, 6-8 hours of sleep, and avoidance of intense physical activity for 24 hours prior to testing, conducted in a silent environment with dim lighting and controlled temperature [6].

Despite its accuracy, IC has limitations for widespread use, including equipment cost, technical expertise requirements, and time-intensive protocols. These practical constraints have driven the development and utilization of predictive equations for estimating REE in both research and clinical contexts.

Comparative Performance of Predictive Equations

Table 1: Comparison of REE predictive equations against indirect calorimetry in overweight and obese adults (n=82) [6]

| Equation | Formula (Male) | Formula (Female) | REE Estimate (kcal/day) | Systematic Error | Intraclass Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect Calorimetry | - | - | 1896 ± 419 | Reference | Reference |

| Harris-Benedict | 66.47 + (13.75×W) + (5×H) - (6.75×A) | 655.10 + (9.56×W) + (1.85×H) - (4.68×A) | 1718 ± 329 | Low | High |

| WHO1 (Weight only) | (11.6 × W) + 879 | (8.7 × W) + 829 | 1756 ± 303 | Low | High |

| WHO2 (Weight & Height) | (11.3 × W) + (16 × H) + 901 | (8.7 × W) - (25 × H) + 865 | 1765 ± 310 | Low | High |

| Mifflin | (9.99×W) + (6.25×H) - (4.92×A) + 5 | (9.99×W) + (6.25×H) - (4.92×A) - 161 | 1607 ± 304 | High | Moderate |

| Owen | 879 + (10.2 × W) | 795 + (7.18 × W) | 1607 ± 284 | High | Moderate |

W = weight (kg), H = height (cm), A = age (years)

A comparative study of 82 overweight and obese adults (BMI ≥25 kg/m²) revealed significant differences in the performance of common predictive equations [6]. The Harris-Benedict, WHO1, and WHO2 equations demonstrated the highest intraclass correlation coefficients and lowest systematic errors when compared to IC measurements. In contrast, the Mifflin and Owen equations consistently underestimated REE in this population [6]. These findings highlight the importance of selecting population-appropriate equations, particularly for overweight and obese individuals where inaccurate estimation can substantially impact weight management interventions.

Special Considerations for Different Populations

The performance of REE predictive equations varies across populations due to differences in body composition, age, and ethnicity. Research indicates that the interplay between BMR, physical exercise, diet, and body composition differs across Caucasian, Hispanic, and Asian populations [33]. This has prompted large-scale studies using diverse cohorts including the UK Biobank (500,000 adults), China Kadoorie Biank (500,000 participants), and Mexico City Prospective Study (100,000 participants) to develop more ethnically appropriate equations [33].

Age represents another critical factor, as BMR decreases with age and with the loss of lean body mass [32]. This decline in FFM with aging explains approximately 60-70% of the observed reduction in REE in older adults. Additionally, sex differences significantly impact REE, with men typically exhibiting higher absolute REE values due to greater lean body mass, even when adjusting for body size [35].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized REE Assessment Protocol

Figure 2: Standardized experimental workflow for REE assessment via indirect calorimetry. Strict protocol adherence ensures measurement accuracy and reliability.

The protocol for measuring REE via indirect calorimetry requires strict standardization to ensure accurate results. As implemented in research settings [6], the methodology includes:

- Subject Preparation: Participants undergo a 12-hour overnight fast, obtain 6-8 hours of sleep, and avoid intense physical activity for 24 hours prior to testing.

- Testing Conditions: Measurements occur in a silent environment with dim lighting and controlled temperature to minimize external influences on metabolic rate.

- Equipment Calibration: The calorimetry system undergoes 30-minute warm-up and calibration with gases of known concentration before measurements.

- Measurement Period: After a 10-minute acclimatization period for reading stabilization, VO₂ and VCO₂ are measured for 20 minutes to calculate REE using Weir's equation.

This protocol controls for factors known to acutely influence metabolic rate, including food intake, physical activity, and environmental stimuli.

Doubly Labeled Water Methodology for Total Energy Expenditure

For measuring total daily energy expenditure in free-living individuals, the doubly labeled water method represents the gold standard. This approach, utilized in endurance limitation studies [37], involves:

- Isotope Administration: Participants ingest water containing stable, non-radioactive isotopes of hydrogen (²H) and oxygen (¹⁸O).

- Urine Collection: Spot urine samples are collected over 7-14 days to measure isotope elimination rates.

- Calculation: The difference in elimination rates between ²H (which leaves the body as water) and ¹⁸O (which exits as both water and carbon dioxide) allows calculation of carbon dioxide production, from which total energy expenditure is derived.

This method has revealed critical insights into human metabolic limits, demonstrating that even elite athletes cannot sustain energy expenditure beyond approximately 2.5 times their BMR for prolonged periods [37].

Advanced Research Applications

Metabolic Biomarkers in Research

Table 2: Promising biomarkers for monitoring metabolic status in research settings [38]

| Metabolic Domain | Biomarkers | Research Application | Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Metabolism | Urinary n-telopeptide, Bone mineral density (BMD), Bone pain assessment | Fracture risk prediction, Bone remodeling monitoring | DXA, Urinary assays, Questionnaires |

| Muscle Metabolism | 24-hour urinary 3-methylhistidine, Protein turnover rates, Perceived exertion scales | Muscle catabolism assessment, Performance prediction | Stable isotope methods, Borg scale, Urinalysis |

| Glucose Metabolism | Tissue lactate levels, Muscle glycogen content, Heart rate variability | Fatigue monitoring, Metabolic fuel utilization | NIRS, Muscle biopsy, ECG monitoring |

| Hydration Status | Body weight changes, Plasma osmolality, Urine specific gravity | Dehydration assessment, Fluid balance monitoring | Weight scales, Plasma analysis, Urine dipsticks |

| Cognitive Function | Actigraphy, Electroencephalography (EEG), Visual analog scales | Cognitive readiness assessment, Fatigue monitoring | Wearable sensors, EEG caps, Questionnaires |

Advanced research in energy metabolism extends beyond REE measurement to include comprehensive metabolic monitoring. The Institute of Medicine has identified promising biomarkers for assessing metabolic status in field research settings [38]. These biomarkers enable researchers to monitor specific aspects of metabolic function and identify deviations from normal physiological ranges.

For muscle metabolism, 24-hour urinary 3-methylhistidine provides a non-invasive marker of muscle protein catabolism, as this compound is not metabolized and reflects myofibrillar protein breakdown [38]. Similarly, hydration status can be monitored through short-term body weight changes coupled with serum sodium or osmolality measurements, providing critical data on fluid balance during metabolic studies [38].

Body Composition Assessment Methods

The accurate assessment of body composition provides essential context for interpreting REE measurements. Research methodologies include:

- Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA): Provides precise measurement of fat mass, lean mass, and bone mineral density with low radiation exposure.

- Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA): Measures resistance and reactance to alternating electrical currents to estimate body composition.

- Air Displacement Plethysmography (ADP): Determines body volume and density to calculate fat and lean mass.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Computed Tomography (CT): Provide highly detailed tissue-specific composition data, including visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue distribution.

Each method operates on different principles and varies in cost, accessibility, and precision, requiring researchers to select appropriate methodologies based on specific research questions and resources.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and methodologies for REE and body composition studies

| Category | Item | Research Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calorimetry | Indirect Calorimeter | Gold standard REE measurement | Requires strict protocol adherence for accurate results |

| Stable Isotopes | ²H₂O (Deuterated water), H₂¹⁸O (Oxygen-18 water) | Total energy expenditure measurement via doubly labeled water | Allows free-living assessment over 1-2 week periods |

| Body Composition | DXA Scanner, BIA Device, ADP System | Fat and fat-free mass quantification | DXA provides three-compartment model data |

| Biomarker Assays | Urinary n-telopeptide kits, 3-methylhistidine assays | Bone and muscle metabolism monitoring | Requires 24-hour urine collection for accuracy |

| Physiological Monitoring | Actigraphy devices, Heart rate variability monitors, EEG systems | Cognitive function and fatigue assessment | Provides objective measures of physiological strain |

| Statistical Analysis | R, STATA, Python, SAS packages | Data analysis and predictive modeling | Essential for developing population-specific equations |

This toolkit summarizes essential resources for conducting rigorous research in energy expenditure and body composition. The listed methodologies enable comprehensive assessment of metabolic status from cellular to whole-body levels, facilitating advanced research into the relationships between body composition, physiological status, and energy metabolism.

For drug development professionals, these tools provide critical endpoints for evaluating metabolic interventions, whether targeting weight management, muscle preservation, or metabolic disease treatment. The combination of precise body composition assessment with accurate REE measurement enables comprehensive metabolic phenotyping that can identify responders and non-responders to therapeutic interventions.

The metabolic basis of REE is fundamentally rooted in body composition, with fat-free mass representing the primary determinant of individual variation in energy expenditure. This relationship forms the foundation for predictive equations that estimate REE across diverse populations, though their accuracy varies significantly, particularly in overweight and obese individuals. Contemporary research methodologies—from indirect calorimetry and doubly labeled water to advanced body composition assessment—provide powerful tools for investigating energy metabolism in both laboratory and free-living settings.

Future research directions should focus on refining predictive models through incorporation of ethnic-specific variables, developing standardized protocols for special populations, and advancing wearable technologies for continuous metabolic monitoring. The integration of metabolic biomarkers with body composition assessment and REE measurement will further enhance our understanding of energy homeostasis, supporting advancements in nutritional science, metabolic drug development, and personalized medicine approaches to weight management and metabolic health.

Developing and Applying REE Predictive Equations: Methodological Approaches

The accurate assessment of energy requirements is a cornerstone of nutritional science, clinical practice, and pharmacological research. Within this domain, resting energy expenditure (REE)—the energy the body requires at complete rest to maintain cellular and systemic functions—represents the largest component of daily energy expenditure, typically accounting for 60-75% of total expenditure in sedentary individuals [39] [40]. The precise determination of REE is therefore critical for developing effective nutritional support strategies, calculating caloric requirements for weight management, and establishing baseline metabolic rates in clinical trials for metabolic disorders.

The historical evolution of REE predictive equations reflects an ongoing scientific endeavor to balance accuracy with practicality. While indirect calorimetry remains the gold standard for measuring REE through direct assessment of oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production, the equipment required is costly, technically demanding, and often inaccessible for routine clinical use or large-scale studies [6] [25]. Consequently, predictive equations—mathematical models that estimate REE based on readily available anthropometric and demographic variables—have become indispensable tools for researchers and clinicians alike. This review traces the development of these equations from their seminal beginnings with Harris-Benedict to contemporary models, evaluating their performance, limitations, and appropriate applications within modern research contexts.

The Founding Formulation: Harris-Benedict Equation

Historical Development and Original Formulations

The Harris-Benedict equation represents the foundational work in the field of metabolic prediction. Published in 1918 and 1919 by James Arthur Harris and Francis Gano Benedict, this equation emerged from extensive biometric studies conducted at the Nutrition Laboratory of the Carnegie Institution [41]. The original research involved 136 male and 103 female subjects, with measurements conducted under strict basal conditions. The equation was derived using multiple regression analysis to correlate measured basal metabolic rate with the key variables of weight, height, and age, separately for men and women [41].

The original Harris-Benedict equations were formulated as follows:

Original Harris-Benedict Equations (1919)

- Men: BMR = 66.473 + (13.7516 × weight in kg) + (5.0033 × height in cm) - (6.755 × age in years)

- Women: BMR = 655.0955 + (9.5634 × weight in kg) + (1.8496 × height in cm) - (4.6756 × age in years)

These equations remained the predominant method for estimating basal metabolic rate for over six decades until concerns about their accuracy in modern populations prompted revisions and new formulations.

The Roza and Shizgal Revision (1984)

By the 1980s, researchers recognized that changes in body composition and lifestyle since the early 20th century might have affected the accuracy of the original Harris-Benedict equations. In 1984, Roza and Shizgal published a revised version based on a re-evaluation of the original data [41]:

Revised Harris-Benedict Equations (Roza and Shizgal, 1984)

- Men: BMR = 88.362 + (13.397 × weight in kg) + (4.799 × height in cm) - (5.677 × age in years)

- Women: BMR = 447.593 + (9.247 × weight in kg) + (3.098 × height in cm) - (4.330 × age in years)

This revision attempted to correct for apparent overestimation in the original formulas while maintaining the same basic mathematical structure and variable composition.

Modern Evolutionary Steps: Key Predictive Equations

The Mifflin-St Jeor Equation (1990)

Recognizing the limitations of the Harris-Benedict equations, Mifflin and St Jeor developed a new predictive equation in 1990 using data from 498 healthy subjects, including both normal-weight and obese individuals [42]. This equation was specifically designed to be more reflective of contemporary body composition and lifestyle:

Mifflin-St Jeor Equations (1990)

- Men: REE = (10 × weight in kg) + (6.25 × height in cm) - (5 × age in years) + 5

- Women: REE = (10 × weight in kg) + (6.25 × height in cm) - (5 × age in years) - 161

The researchers reported that this new equation was more accurate than the Harris-Benedict equations, which overestimated measured REE by approximately 5% in their study population [42]. The simplified structure also enhanced its utility for clinical applications.

WHO/FAO/UNU Equations (1985)

The World Health Organization, in collaboration with the Food and Agriculture Organization and United Nations University, developed predictive equations that offered alternative formulations based on weight alone or combined weight and height [6] [43]:

WHO/FAO/UNU Equations (1985)

- Men (weight only): REE = (11.6 × weight in kg) + 879

- Women (weight only): REE = (8.7 × weight in kg) + 829

- Men (weight & height): REE = (11.3 × weight in kg) + (16 × height in meters) + 901

- Women (weight & height): REE = (8.7 × weight in kg) - (25 × height in meters) + 865

These equations were developed through international collaborative efforts and were designed for global application across diverse populations.

Owen and Colleagues' Equations (1986-1987)

Owen and colleagues developed alternative equations specifically for normal-weight individuals, using data that emphasized the relationship between body weight and REE [6]:

Owen Equations (1986-1987)

- Men: REE = 879 + (10.2 × weight in kg)

- Women: REE = 795 + (7.18 × weight in kg)

These equations notably excluded height and age as variables, focusing solely on body weight as the primary predictor of resting energy expenditure.

Comparative Analysis: Experimental Validation of Predictive Equations

Methodological Approaches for Equation Validation

The validation of predictive equations for REE follows established experimental protocols centered around comparison with indirect calorimetry as the reference standard. The typical methodology includes:

Subject Preparation: Participants are tested after an overnight fast (10-12 hours), having abstained from caffeine, alcohol, and strenuous physical activity for at least 24 hours. A rest period of 30 minutes precedes measurement to ensure a true resting state [39] [6].

Measurement Conditions: REE measurements are conducted in a thermoneutral environment with dim lighting and minimal auditory stimulation. Subjects remain awake while lying supine, breathing quietly through a mouthpiece or ventilated hood system [39].

Indirect Calorimetry Protocol: Using metabolic carts such as the Deltatrac II or MedGem, measurements of oxygen consumption (VO₂) and carbon dioxide production (VCO₂) are taken over 15-30 minutes, with the first 5-10 minutes typically discarded to allow for stabilization [39] [40]. REE is then calculated using the Weir equation: REE = [3.9(VO₂) + 1.1(VCO₂)] × 1440 [6].

Statistical Analysis: Comparison between predicted and measured REE involves multiple statistical approaches including paired t-tests, correlation analysis, Bland-Altman plots for assessing agreement, and calculation of the percentage of subjects whose REE is predicted within ±10% of measured values [6] [40].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the standard experimental protocol for validating predictive equations against indirect calorimetry:

Performance Comparison Across Populations

Extensive research has compared the accuracy of various predictive equations against measured REE across different population groups. The following table summarizes key comparative findings from multiple validation studies:

Table 1: Comparative Accuracy of Predictive REE Equations Across Population Subgroups

| Population | Sample Characteristics | Most Accurate Equation | Accuracy Rate | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Non-obese & Obese | Systematic review of multiple studies | Mifflin-St Jeor | ~80% within ±10% of measured REE | Most reliable for both non-obese and obese individuals; narrowest error range | [44] |

| Overweight/Obese Adults | 82 participants, BMI ≥25 kg/m² | Harris-Benedict, WHO1, WHO2 | High intraclass correlation | All equations significantly different from IC; HB and WHO equations least underestimating | [6] |

| Weight-Reduced Women | 51 weight-reduced women (BMI ≤25) | Harris-Benedict | Overestimation: 105±135 kcal/day | HB overestimated significantly less in weight-reduced vs. overweight women | [39] |

| Japanese Schizophrenia Patients | 110 patients on antipsychotics | Harris-Benedict | Strongest correlation (r=0.617) | No significant bias in Bland-Altman analysis; most appropriate for this population | [40] |

| Hospital In/Outpatients | 93 adult patients | WHO (weight & height) | Smallest prediction error (233 kcal/d) | Best performance across outpatient, inpatient, and underweight subgroups | [43] |

| African American Women | Various BMI categories | None satisfactory | Significant overestimation | HB overestimated more in AA vs. Caucasian women (P<0.001) | [39] |

Quantitative Comparison of Prediction Errors

The following table presents specific numerical data on prediction errors and bias for major equations across multiple studies:

Table 2: Quantitative Prediction Errors of Major REE Equations (kcal/day)

| Equation | Population | Bias (Mean Difference from IC) | Limits of Agreement | Accuracy (% within ±10% of IC) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harris-Benedict | Never-overweight women | +160 ±125 | +35 to +285 | ~60% | [39] |

| Harris-Benedict | Overweight women | +295 ±189 | +106 to +484 | ~40% | [39] |

| Harris-Benedict | Weight-reduced women | +105 ±135 | -30 to +240 | ~70% | [39] |

| Mifflin-St Jeor | Overweight/obese adults | -289* | Wide range | ~45% | [6] |

| WHO (weight & height) | Overweight/obese adults | -140* | Wide range | ~55% | [6] |

| Owen | Overweight/obese adults | -289* | Wide range | ~45% | [6] |

| Harris-Benedict | Japanese schizophrenia | -1.7 ±282.3 | -284 to +280.6 | Not reported | [40] |

| Mifflin-St Jeor | Japanese schizophrenia | -46.7 ±290.3 | -337 to +243.6 | Not reported | [40] |

*Values estimated from graphical data; statistical significance not reported.

Specialized Equations and Emerging Approaches

Population-Specific Formulations

As limitations of general predictive equations became apparent, researchers developed specialized formulations for specific patient populations and clinical scenarios:

Ireton-Jones Equations: Developed for ventilated burn patients, accounting for the hypermetabolic state of trauma and burns, with adjustments for mechanical ventilation [45].

Fusco Formula: Designed specifically for morbidly obese ICU patients to prevent overfeeding, incorporating both metric and imperial measurements [45].

Frankenfield Equations: Created for sepsis and trauma patients, incorporating minute volume and hemoglobin measurements based on correlations with metabolic rate in these populations [45].

Incorporation of Body Composition Data

Recent research has explored the integration of body composition metrics into predictive models. A 2020 study developed new equations incorporating raw bioimpedance analysis (BIA) variables, demonstrating slightly improved accuracy compared to traditional equations [25]. The equation incorporating BIA variables showed the highest accuracy at the individual level (70.3% for men, 72.3% for women within ±10% of measured REE) [25].

The fundamental relationships between body composition parameters and energy expenditure can be visualized as follows:

Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Tools

The experimental validation of predictive equations requires specific methodological approaches and technical equipment. The following table details key research reagents and tools essential for conducting validation studies in this field:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Tools for REE Equation Validation

| Category | Specific Tool/Instrument | Research Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calorimetry Systems | Deltatrac II Metabolic Monitor (SensorMedics) | Gold standard REE measurement via indirect calorimetry | Requires regular calibration with reference gases; hood or mouthpiece systems [39] |

| Portable Calorimetry | MedGem Portable Indirect Calorimeter (HealtheTech) | Field measurements of REE | Validated against metabolic carts; useful for clinical settings [40] |

| Body Composition | DXA (Dual-energy X-ray Absorptiometry) | Precise measurement of fat mass and fat-free mass | Critical for understanding body composition-REE relationships [39] |

| Bioimpedance Analysis | BIA devices with phase angle measurement | Estimation of body composition and cellular health | Raw BIA variables (phase angle) may improve REE prediction accuracy [25] |

| Anthropometric Equipment | Digital stadiometer (Heightronic) | Accurate height measurement | Essential input variable for most predictive equations [39] |

| Anthropometric Equipment | Calibrated digital scale (Scale-tronix) | Precise weight measurement | Required for all predictive equations; calibrated regularly [39] |

| Data Analysis | Bland-Altman statistical method | Assessment of agreement between predicted and measured REE | Superior to correlation alone for method comparison studies [6] [40] |

| Nutrition Analysis | Nutrition Data System for Research (NDS-R) | Calculation of dietary energy content during validation studies | Ensures precise energy intake during controlled feeding protocols [39] |

The evolution of predictive equations for resting energy expenditure—from the pioneering Harris-Benedict formulation to contemporary models—reflects an ongoing scientific pursuit of metabolic prediction accuracy. The evidence synthesized in this review demonstrates that while the Mifflin-St Jeor equation generally shows the highest accuracy across diverse populations, no single equation achieves perfect prediction for all individuals or population subgroups [44]. The performance of these equations is significantly influenced by factors such as weight history, ethnicity, body composition, and health status [39].

For researchers and drug development professionals, several critical implications emerge from this analysis. First, the selection of predictive equations should be guided by the specific population under study, with careful consideration of the demonstrated biases for particular demographic or clinical groups. Second, when precise energy expenditure assessment is methodologically critical, indirect calorimetry remains indispensable despite its practical limitations [44]. Finally, emerging approaches incorporating body composition data and population-specific adjustments represent promising avenues for improving prediction accuracy.

Future research should focus on developing and validating equations in currently underrepresented populations, including diverse ethnic groups, older adults, and specific clinical populations. The integration of novel biomarkers and body composition metrics may further enhance prediction accuracy. Until such advances mature, researchers should apply existing equations with appropriate caution, recognizing their limitations and the potential clinical implications of estimation errors in both research and practice.