Genome-Scale Metabolic Model Construction: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

This comprehensive review explores the evolving methodology of genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) construction, integrating foundational principles with cutting-edge computational advances.

Genome-Scale Metabolic Model Construction: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the evolving methodology of genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) construction, integrating foundational principles with cutting-edge computational advances. We examine the transition from traditional constraint-based reconstruction to contemporary approaches incorporating machine learning, multi-omics integration, and enzyme kinetics prediction. The article provides systematic frameworks for model troubleshooting, validation, and application across biomedical domains including antimicrobial development, live biotherapeutic design, and pathogen metabolism analysis. Targeted toward researchers and drug development professionals, this resource offers practical guidance for constructing, optimizing, and applying high-quality GEMs to address complex biological questions and therapeutic challenges.

The Foundation of GEMs: From Basic Principles to Genome-Wide Metabolic Networks

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) represent complex metabolic networks of organisms using stoichiometric matrices to enable systems-level analysis of metabolic functions. These computational tools integrate genomic annotation, biochemical knowledge, and physiological constraints to simulate metabolic capabilities under specific conditions. GEMs have become indispensable in diverse applications ranging from metabolic engineering and drug target identification to understanding microbial ecology and developing live biotherapeutic products. This protocol outlines the core components, stoichiometric principles, and reconstruction methodologies that form the foundation of GEM development and application, providing researchers with a structured framework for model construction and validation.

Genome-scale metabolic models are knowledge-based in silico representations of the metabolic network of an organism, constructed from genomic and biochemical information [1]. They capture a systems-level view of the entirety of metabolic functions within a cell, representing complex interconnections between genes, proteins, reactions, and metabolites [1]. The mathematical foundation of GEMs relies on the stoichiometric matrix (S), where each element Sij represents the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j [2]. This matrix formulation enables sophisticated constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) methods, including Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), to predict metabolic phenotypes and flux distributions under specified conditions [1] [3].

The reconstruction and analysis of GEMs has evolved into a powerful systems biology approach with applications spanning basic understanding of genotype-phenotype relationships to solving biomedical and environmental challenges [1]. Well-curated GEMs exist for over 100 prokaryotes and eukaryotes, providing organized and mathematically tractable representations of these organisms' metabolic networks [1]. The utility of GEMs extends beyond mere metabolic mapping; they provide a framework for integrating species-specific knowledge and complex 'omics data, facilitating the translation of biological hypotheses into testable predictions of metabolic phenotypes [1] [4].

Core Components of GEMs

Fundamental Elements

The reconstruction of genome-scale metabolic models requires the systematic assembly of several core components that collectively represent the metabolic network of an organism.

Table 1: Core Components of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models

| Component | Description | Function in Model |

|---|---|---|

| Genes | DNA sequences encoding metabolic enzymes | Provide genetic basis for metabolic reactions; included via gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations |

| Proteins | Enzymes catalyzing biochemical reactions | Implement catalytic functions; connect genes to reactions |

| Reactions | Biochemical transformations between metabolites | Form the edges of the metabolic network; include metabolic, transport, and exchange reactions |

| Metabolites | Chemical compounds participating in reactions | Form the nodes of the metabolic network; must be mass and charge-balanced |

| Stoichiometric Matrix | Mathematical representation of reaction stoichiometry | Core mathematical structure; enables constraint-based analysis |

Gene-Protein-Reaction Associations

Gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations use Boolean expressions to encode the nonlinear mapping between genes and reactions, accounting for metabolic complexities such as multimeric enzymes, multifunctional enzymes, and isoenzymes [1]. These associations define the protein complexes required to catalyze each metabolic reaction and are essential for predicting the metabolic consequences of genetic perturbations. For example, in the S. suis iNX525 model, GPR associations were obtained from reference models of related organisms (Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, and S. pyogenes) using sequence homology criteria (identity ≥ 40% and match lengths ≥ 70%) [2]. Innovative approaches have been developed to represent GPR associations directly within the stoichiometric matrix of GEMs, enabling extension of flux sampling approaches to gene sampling and facilitating quantification of uncertainty [1].

Biomass Composition

The biomass objective function represents the metabolic requirements for cellular growth by accounting for all necessary biomass precursors and their relative contributions. This includes macromolecular components such as proteins, DNA, RNA, lipids, and other cellular constituents. For example, in the S. suis iNX525 model, the biomass composition was adapted from Lactococcus lactis, containing proteins (46%), DNA (2.3%), RNA (10.7%), lipids (3.4%), lipoteichoic acids (8%), peptidoglycan (11.8%), capsular polysaccharides (12%), and cofactors (5.8%) [2]. The specific DNA, RNA, and amino acid compositions were calculated from the genome and protein sequences of S. suis [2].

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Biomass Composition in S. suis iNX525 Model

| Biomass Component | Percentage | Composition Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Proteins | 46% | Calculated from S. suis protein sequences |

| DNA | 2.3% | Calculated from S. suis genome sequence |

| RNA | 10.7% | Calculated from S. suis genome sequence |

| Lipids | 3.4% | Literature values for free fatty acids |

| Lipoteichoic Acids | 8% | Literature values |

| Peptidoglycan | 11.8% | Literature values |

| Capsular Polysaccharides | 12% | Literature values |

| Cofactors | 5.8% | Literature values |

Stoichiometric Principles and Mathematical Foundation

The Stoichiometric Matrix

The core mathematical structure of GEMs is the stoichiometric matrix S, where each element Sij represents the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j [2]. This matrix formulation captures the topology and stoichiometry of the entire metabolic network, enabling mathematical analysis of metabolic capabilities. The stoichiometric matrix typically has dimensions of m × n, where m is the number of metabolites and n is the number of reactions in the network. For example, the S. suis iNX525 model comprises 708 metabolites and 818 reactions, resulting in a stoichiometric matrix of corresponding dimensions [2].

Flux Balance Analysis

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is the primary constraint-based method used to analyze GEMs. FBA operates on the principle of mass conservation in a network under pseudo-steady state conditions, using a stoichiometric matrix and biologically relevant objective functions to determine optimal reaction flux distributions [3]. The mathematical formulation of FBA is represented as:

Maximize Z = cᵀv Subject to: S·v = 0 vmin ≤ v ≤ vmax

Where Z is the objective function (typically biomass production), c is a vector of weights indicating which metabolites contribute to the objective, v is the flux vector through each reaction, S is the stoichiometric matrix, and vmin and vmax are lower and upper bounds on reaction fluxes, respectively [2]. This linear programming formulation allows for prediction of metabolic behavior under specified environmental and genetic conditions.

Model Constraints

The predictive capability of GEMs relies on appropriate constraints that define the biological and environmental limitations on metabolic fluxes:

- Stoichiometric constraints: Enforce mass conservation through the equation S·v = 0, ensuring that metabolite production balances consumption at steady state [2].

- Capacity constraints: Define upper and lower bounds (vmin, vmax) on reaction fluxes based on enzyme capacities or thermodynamic considerations [3].

- Environmental constraints: Limit uptake and secretion rates based on nutrient availability in the growth environment [1] [3].

- Gene knockout constraints: Enable simulation of genetic perturbations by setting fluxes of reactions associated with deleted genes to zero [2].

GEM Reconstruction Protocol

Reconstruction Workflow

The reconstruction of high-quality genome-scale metabolic models follows a systematic protocol encompassing multiple stages of curation and validation.

Detailed Methodologies

Genome Annotation and Draft Reconstruction

The initial step involves identifying genes encoding metabolic enzymes and establishing their functional annotations through homology-based methods [1]. Automated pipelines such as ModelSEED [2], RAVEN [1], AuReMe/Pantograph [1], CarveMe [1], and KBase [1] can generate draft models from annotated genomes. For the S. suis iNX525 model, the genome was initially annotated using RAST and then processed through ModelSEED for automated construction [2]. To improve accuracy, template-based approaches can be employed using previously curated GEMs of closely related organisms as references [2].

Manual Curation and Gap Analysis

Manual curation addresses limitations in automated reconstruction by incorporating organism-specific biochemical knowledge. This process involves:

- Gap analysis: Identifying metabolic gaps that prevent synthesis of essential biomass components using tools like gapAnalysis in the COBRA Toolbox [2].

- Reaction addition: Incorporating missing biochemical reactions based on literature evidence, transporter annotations from databases like TCDB, and new gene functions assigned via BLASTp against UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot [2].

- Mass and charge balancing: Ensuring all reactions are chemically consistent by adding H₂O or H⁺ as needed, verified using checkMassChargeBalance programs [2].

Biomass Formulation

Develop a comprehensive biomass objective function representing the metabolic requirements for cellular growth:

- Determine macromolecular composition percentages from literature or related organisms [2].

- Calculate specific DNA, RNA, and amino acid compositions from genomic and proteomic sequences [2].

- Incorporate experimentally determined compositions for complex components like lipoteichoic acids and capsular polysaccharides [2].

- Formulate the biomass equation as a weighted sum of all biomass precursors.

Model Validation

Validate the metabolic model through multiple approaches:

- Growth simulations: Compare in silico predictions with experimental growth phenotypes under different nutrient conditions [2].

- Gene essentiality: Assess agreement between model-predicted essential genes and experimental mutant screens [2].

- Physiological consistency: Ensure model predictions align with known physiological capabilities of the organism.

For S. suis iNX525, growth assays in chemically defined medium (CDM) with systematic nutrient omissions (leave-one-out experiments) were used to validate model predictions, with growth rates measured by optical density at 600 nm and normalized to growth in complete CDM [2].

Applications of GEMs

Genome-scale metabolic models have diverse applications across biotechnology, biomedicine, and basic research:

- Metabolic Engineering: Identification of gene knockout and overexpression targets for strain optimization [5].

- Drug Target Discovery: Prediction of essential metabolic pathways and reactions for antimicrobial development [2].

- Host-Pathogen Interactions: Analysis of metabolic dependencies during infection [2].

- Microbiome Research: Modeling metabolic interactions in complex microbial communities [3] [4].

- Live Biotherapeutic Products: Guiding the design of microbial consortia for therapeutic applications [4].

In drug discovery, GEMs of pathogens like S. suis enable identification of dual-purpose targets essential for both growth and virulence factor production [2]. For microbiome applications, GEMs facilitate modeling of cross-feeding interactions and nutrient cycling within microbial communities, as demonstrated in sponge holobiont systems [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for GEM Development

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB toolbox for constraint-based modeling | Model simulation, gap-filling, flux variability analysis [2] |

| ModelSEED | Automated pipeline for draft model reconstruction | Rapid generation of draft models from annotated genomes [2] |

| RAST | Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology | Genome annotation for model reconstruction [2] |

| AGORA2 | Resource of curated GEMs for gut microbes | Modeling host-microbiome interactions [4] |

| GUROBI Optimizer | Mathematical optimization solver | FBA simulation for large-scale models [2] |

| MEMOTE | Test suite for model quality assessment | Standardized model evaluation and quality reporting [2] |

| BiGG Database | Curated metabolic database | Reference for biochemical reaction information [1] |

| UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot | Curated protein sequence database | Functional annotation of metabolic enzymes [2] |

Genome-scale metabolic models provide a powerful framework for systems-level analysis of cellular metabolism. The core components—genes, proteins, reactions, metabolites, and their stoichiometric relationships—form a mathematical representation that enables prediction of metabolic phenotypes under various genetic and environmental conditions. The reconstruction protocol outlined here emphasizes the importance of both automated and manual curation processes to develop high-quality models that accurately reflect organismal metabolism. As GEM methodologies continue to advance, they offer increasingly sophisticated approaches for addressing fundamental biological questions and solving applied problems in biotechnology and medicine. Future directions include improved integration of regulatory information, better representation of multi-scale phenomena, and enhanced methods for modeling microbial communities.

The construction of genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) represents a cornerstone of systems biology, enabling researchers to translate genomic information into predictive computational models of metabolic networks. The journey began with Haemophilus influenzae, the first free-living organism to have its entire genome sequenced and its metabolic network reconstructed [6]. This pioneering work in 1999 established the foundational framework for GEM development, transforming how we investigate the relationship between genotype and phenotype across the tree of life [7]. This application note details the historical progression, core methodologies, and practical protocols in GEM construction, providing a resource for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in metabolic network analysis.

The Foundational Model:Haemophilus influenzae

The first whole-genome metabolic model of H. influenzae strain Rd was a milestone in theoretical biology [6]. This model, reconstructed from the annotated genome sequence, comprised 461 metabolic reactions operating on 367 intracellular metabolites and 84 extracellular metabolites [6]. The reconstruction process involved meticulously mapping genes to proteins and subsequently to biochemical reactions, thereby defining the organism's metabolic genotype.

The initial model was subdivided into six subsystems, and its underlying pathway structure was determined using extreme pathway analysis [6]. This approach, based on stoichiometric, thermodynamic, and system-specific constraints, allowed researchers to address several physiological questions: it helped curate the genome annotation by identifying reactions without functional support, predicted co-regulated gene products, determined minimal substrate requirements for producing essential biomass components, and identified critical gene deletions under different environmental conditions [6]. Under minimal substrate conditions, 11 genes were found to be critical, with six remaining essential even in the more nutrient-rich conditions reflecting the human host environment [6].

Table 1: Key Statistics of the First Genome-Scale Metabolic Model

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Organism | Haemophilus influenzae Rd |

| Publication Year | 1999/2000 [6] [7] |

| Total Reactions | 461 [6] |

| Intracellular Metabolites | 367 [6] |

| Extracellular Metabolites | 84 [6] |

| Primary Analysis Method | Extreme Pathway Analysis [6] |

Expansion and Evolution of GEM Construction

Since the inception of the H. influenzae model, the field of GEM construction has experienced exponential growth. As of 2022, GEMs have been constructed for 5,897 bacteria, alongside numerous models for eukaryotic organisms [7]. Key model organisms such as Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Bacillus subtilis have seen multiple iterative updates of their models, enhancing the coverage of gene-protein-reaction associations and improving predictive accuracy [7].

The fundamental principle of GEMs is the transformation of cellular growth and metabolism into a mathematical framework based on a stoichiometric matrix, which is solved for an optimal solution at a steady state [7]. The primary algorithm for simulating phenotypic states from these models is Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), which computes the flow of metabolites through the metabolic network, enabling predictions of growth rates or metabolite production [7].

Table 2: Evolution of GEMs for Key Model Organisms

| Organism | Number of Reported GEMs | Notable Advancements |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | 13 | Development of Metabolism-Expression (ME) models that reconstruct complete transcription and translation pathways [7]. |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 13 | Latest model (Yeast8) can dissect metabolic mechanisms at multiscale levels [7]. |

| Bacillus subtilis | 7 | Integration of enzymatic data for central carbon metabolism to guide strain engineering [7]. |

Advanced Methodologies: From Constraint-Based to Multiscale Models

Basic GEMs have evolved into sophisticated multiscale models that integrate additional biological layers to more accurately simulate in vivo conditions. The limitation of traditional GEMs, which primarily capture gene-protein-reaction relationships, has prompted the development of models that incorporate various constraints and omics data.

Constraint-Based Modeling

To enhance the predictive power of GEMs, several constraint-based approaches have been developed:

- Thermodynamic Constraint Models: These models incorporate the directionality and Gibbs free energy of metabolic reactions to eliminate thermodynamically infeasible pathways. Key algorithms include Thermodynamically based Metabolic Flux Analysis (TMFA) and network-embedded thermodynamic analysis [7].

- Enzymatic Constraint Models: Frameworks like GECKO integrate enzyme concentration data and catalytic constants into the models, accounting for the proteomic cost of metabolic fluxes [7].

- Kinetic Constraint Models: Approaches such as ORACLE and Ensemble Modeling introduce kinetic parameters to evaluate the dynamic properties of metabolic systems, moving beyond steady-state assumptions [7].

Multi-Omics Integration

The development of high-throughput technologies has enabled the integration of multi-omics data (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics) directly into GEMs. Algorithmic frameworks such as iMAT, MADE, and GIM3E leverage these data to create context-specific models, improving their biological relevance and predictive accuracy for particular conditions [7]. Furthermore, tools like TIGER and FlexFlux integrate transcriptional regulatory networks with GEMs, allowing for the simulation of complex regulatory-metabolic interactions [7].

Essential Protocols and Workflows

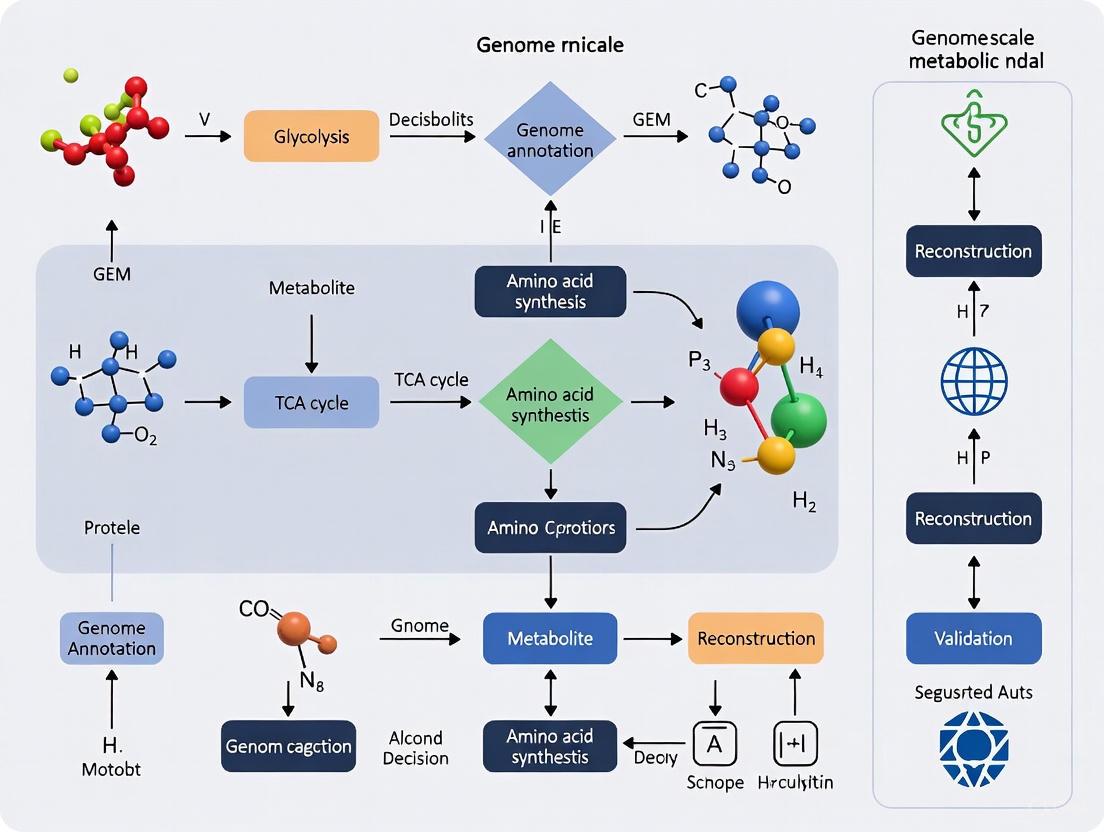

Workflow for GEM Construction and Analysis

The following diagram outlines the generalized workflow for constructing and analyzing genome-scale metabolic models, from genomic data to model validation and application.

Protocol: Tn-seq Mutant Library Generation forHaemophilus influenzae

This protocol details the generation of a transposon sequencing (Tn-seq) mutant library, a genome-wide screen used to identify conditionally essential bacterial genes, such as those involved in virulence [8]. The following workflow summarizes the key stages of this protocol.

Part I: Generation of Mutant Library [8]

Transposition Reaction

- Prepare a fresh 6x transposition buffer containing glycerol, DTT, Hepes, BSA, NaCl, and MgCl₂.

- Combine 3.3 µL of 6x Transposition Buffer with 0.5-1.0 µg recipient DNA (e.g., chromosomal DNA of the target strain), 0.5-1.0 µg donor DNA containing the mariner transposon with an MmeI restriction site, 1 µL recombinant Himar1 transposase, and sterile dH₂O to a total volume of 20 µL.

- Mix and incubate for 4 hours at 30°C.

- Inactivate the transposase by heating at 75°C for 10 minutes.

- Precipitate the DNA using sodium acetate, glycogen, and absolute ethanol.

Repair of Transposition Reaction

- Resuspend the pellet and add T4 DNA polymerase Reaction Buffer, BSA, dNTP mix, and T4 DNA polymerase.

- Incubate for 30 minutes at 16°C to repair the transposed DNA.

- Inactivate the polymerase at 75°C for 10 minutes and precipitate the DNA again.

Transformation and Library Selection

- Transform the repaired transposition reaction into naturally competent non-typeable H. influenzae.

- Plate the transformation on selective supplemented Brain Heart Infusion (sBHI) agar plates.

- Harvest the mutants by adding PBS, scrape the plates, and pool all colonies. The resulting library can be used for functional screens under challenge conditions (e.g., survival in environmental air).

Part II: Mutant Library Readout and Data Analysis [8]

Genomic DNA Preparation and Adapter Ligation

- Extract genomic DNA from the mutant library before and after screening using a Qiagen Genomic-tip.

- Digest the genomic DNA with MmeI, which cuts at the specific site engineered within the transposon.

- Ligate sequence adapters to the digested fragments.

PCR Amplification and Sequencing

- Amplify the fragments using primers complementary to the ligated adapters.

- The resulting PCR product is sequenced using a high-throughput platform like Illumina MiSeq.

Data Analysis

- The sequencing reads are mapped to the genome to identify transposon insertion sites and their abundance.

- Use web-based analysis software such as ESSENTIALS to identify genes essential for growth under the tested condition by comparing insertion abundances between control and challenge libraries.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Tn-seq and Genomic Analysis

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Himar1 Mariner Transposase | Catalyzes random insertion of transposon into TA dinucleotide sites in the genome. | Essential for in vitro transposition reaction to generate random mutant library [8]. |

| MmeI Restriction Enzyme | Cuts DNA at a specific site (TCCRAC) 20/18 bases away from its recognition site. | Used to digest genomic DNA, generating a short fragment that includes the transposon end and adjacent genomic sequence for sequencing [8]. |

| T4 DNA Polymerase | Possesses DNA polymerase and single-stranded exonuclease activities. | Repairs the transposed DNA after the in vitro transposition reaction [8]. |

| Qiagen Genomic-tip Columns | Silica-gel membrane-based technology for purification of high-molecular-weight genomic DNA. | Essential for obtaining high-quality genomic DNA required for the Tn-seq library preparation [8]. |

| ESSENTIALS Software | Web-based tool for the analysis of Tn-seq data. | Identifies conditionally essential genes by statistically comparing transposon insertion frequencies between libraries [8]. |

The historical trajectory from the first Haemophilus influenzae GEM to the thousands of models in existence today underscores the transformative impact of this methodology on systems biology and metabolic engineering. The initial reconstruction, containing hundreds of reactions, has evolved into multiscale models that integrate thermodynamic, enzymatic, and regulatory constraints. Supported by robust experimental protocols like Tn-seq and powerful computational algorithms, GEMs provide an indispensable framework for elucidating genotype-phenotype relationships. As the field progresses with the integration of machine learning and more complex multi-omics data, GEMs will continue to be pivotal in advancing scientific discovery and streamlining drug and bioproduction development.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are computational representations of the metabolic network of an organism, and their core component is the set of Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) associations [9]. These logical rules mathematically define the connection between an organism's genes and its metabolic capabilities by explicitly describing how genes encode proteins (enzymes) that catalyze specific biochemical reactions [10]. GPR rules use Boolean logic (AND and OR operators) to represent the genetic basis of metabolism: the AND operator joins genes encoding different subunits of the same enzyme complex, while the OR operator joins genes encoding distinct isozymes that can catalyze the same reaction [10].

The reconstruction of accurate GPRs is therefore a fundamental step in building high-quality GEMs, transforming an abstract network of biochemical reactions into a genotype-prediction model capable of simulating the metabolic consequences of genetic perturbations [11]. This protocol details the methods for establishing these critical genetic links, enabling researchers to move from a genome sequence to a functional, predictive metabolic model.

Key Concepts and Quantitative Landscape

A survey of current resources reveals that GEMs have been reconstructed for thousands of organisms. The table below summarizes the current status of manually and automatically reconstructed GEMs across different domains of life [9].

Table 1: Current Status of Reconstructed Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (as of February 2019)

| Domain of Life | Total GEMs | Manually Reconstructed | Example Organisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | 5,897 | 113 | Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| Archaea | 127 | 10 | Methanosarcina acetivorans |

| Eukaryotes | 215 | 60 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Homo sapiens |

The complexity of GPR associations within a model can be statistically analyzed. In the E. coli iAF1260 model, for instance [11]:

- Over 16% of enzymes are protein complexes (requiring AND logic in GPRs).

- Approximately 31% of metabolic reactions are catalyzed by multiple isozymes (requiring OR logic in GPRs).

- More than 72% of reactions are catalyzed by at least one promiscuous enzyme.

This logical structure of GPR associations can be visualized as a network, as shown in the diagram below.

Diagram 1: Logic of GPR associations. AND operators join genes encoding subunits of a complex. OR operators join genes encoding isozymes.

Protocols for GPR Reconstruction

Protocol 1: Manual Reconstruction and Curation of GPRs

Manual curation remains the gold standard for developing high-quality, reference-grade GEMs. This protocol is essential for model organisms or when high predictive accuracy is required.

Table 2: Key Data Sources for Manual GPR Reconstruction

| Data Source | Type of Information | Role in GPR Reconstruction |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Annotation | Gene identities and locations | Provides the initial list of metabolic genes [10]. |

| UniProt | Protein functional data, complex subunits | Provides evidence for protein complexes and isoform data [10] [12]. |

| KEGG | Pathway maps, enzyme nomenclature | Validates reaction assignments and fills pathway gaps [10] [13]. |

| MetaCyc | Curated biochemical pathways | Provides experimentally verified metabolic information [10]. |

| Complex Portal | Protein-protein interactions, complexes | Critical for defining AND relationships in GPR rules [10]. |

| Scientific Literature | Experimental biochemical evidence | Provides direct validation for GPR associations [10]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Gene List Compilation: Generate a comprehensive list of metabolic genes from the organism's genome annotation file (e.g., GFF format) or databases like NCBI.

- Reaction Assignment: Assign metabolic reactions to each gene product based on enzyme commission (EC) numbers and homology to well-annotated genes in reference databases (KEGG, MetaCyc).

- Protein Complex and Isozyme Resolution: For each reaction, consult UniProt and the Complex Portal to determine:

- If the reaction is catalyzed by a protein complex (requires AND logic between subunit genes).

- If multiple distinct proteins or complexes can catalyze the reaction (requires OR logic between genes/complexes).

- Boolean Rule Formulation: Write the GPR rule in Boolean logic format. For example:

- A homomeric enzyme:

Gene_A - A heteromeric complex:

Gene_A and Gene_B - Multiple isozymes:

Gene_C or Gene_D - A complex with isozymes:

(Gene_A and Gene_B) or (Gene_C and Gene_D)

- A homomeric enzyme:

- Experimental Validation: Use phenotypic data (e.g., growth on different carbon sources) and gene essentiality data to test and refine the GPR rules. A correctly formulated GPR should accurately predict the growth outcome of gene knockout experiments [9] [13].

Protocol 2: Automated Reconstruction Using GPRuler

For high-throughput reconstruction or for non-model organisms, automated tools are highly efficient. GPRuler is an open-source Python framework designed to fully automate GPR reconstruction [10].

Workflow: The GPRuler pipeline automates the information retrieval and logic assembly steps of GPR creation, as illustrated below.

Diagram 2: GPRuler automated reconstruction workflow.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Input: Provide the tool with either just the name of the target organism or an existing draft metabolic model (in SBML format) that lacks GPR associations.

- Execution: Run the GPRuler pipeline. The tool will automatically:

- Query its integrated biological databases (MetaCyc, KEGG, UniProt, Complex Portal, etc.) to retrieve relevant gene, protein, and complex information for the target organism.

- Process this information to identify protein complexes (requiring AND operators) and isozymes (requiring OR operators).

- Assemble the correct Boolean GPR rule for each metabolic reaction.

- Output: Obtain a curated SBML model containing the GPR rules. The tool has demonstrated high accuracy in reproducing GPR rules in benchmark models for Homo sapiens and Saccharomyces cerevisiae [10].

Advanced Applications and Integration

Stoichiometric Representation for Gene-Level Phenotype Prediction

A advanced use of GPRs is their transformation into a stoichiometric representation that can be integrated directly into the model's stoichiometric matrix [11]. This method explicitly represents the enzyme (or subunit) encoded by each gene as a pseudo-metabolite in the model. This transformation enables constraint-based analysis to predict phenotypes directly at the gene level, overcoming limitations of traditional Boolean interpretation.

Procedure:

- Model Transformation: Decompose reversible reactions and reactions catalyzed by multiple isozymes into individual, irreversible reactions.

- Introduce Enzyme Usage Variables: For each gene, add a new "enzyme usage" reaction (

u_gene) that accounts for the total flux carried by the respective enzyme or subunit. - Reformulate Constraints: Incorporate these new variables and pseudo-species into the stoichiometric matrix, creating an extended model.

- Perform Gene-Level Analysis: Apply standard constraint-based methods (e.g., FBA, pFBA) to the extended model. The solution vector will now include fluxes for the enzyme usage variables, providing a direct link between gene expression and metabolic flux [11].

Integration with Omics Data Using ICON-GEMs

GPRs are essential for integrating transcriptomic data into GEMs. The ICON-GEMs method is an innovative approach that integrates gene co-expression networks with GEMs to improve the prediction of condition-specific flux distributions [14].

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Data Preparation: Process gene expression profiles (e.g., RNA-seq data) for the condition of interest, handling missing values and outliers.

- Co-expression Network Construction: Calculate pairwise Pearson correlation coefficients between all genes and transform them into a binary adjacency matrix using a defined threshold.

- Model Constraining: Use the E-flux method to set the upper bounds for reaction fluxes based on the expression levels of the associated genes, as defined by the GPR rules.

- Quadratic Programming Optimization: Solve the ICON-GEMs formulation, which maximizes the alignment between pairs of reaction fluxes and the correlation of their corresponding genes in the co-expression network. The objective function is:

Maximize Σ (qi * qj) for all reaction pairs (i, j) whose genes are linked in the co-expression network.

Where

qrepresents transformed reaction flux values, subject to the standard stoichiometric and capacity constraints [14].

Validation and Experimental Design

Protocol for Validating GPRs via Phenotypic Assays

Computationally derived GPR rules must be validated experimentally. The most common method is to compare in silico predictions of gene essentiality and substrate utilization with in vivo experimental results.

Experimental Design:

- In silico Prediction:

- Gene Essentiality: For each gene in the model, simulate a knockout by setting its activity to

FALSEin the GPR rule. Predict growth under a defined condition (e.g., minimal glucose medium). A gene is predicted to be essential if the simulated growth rate is zero. - Substrate Utilization: Simulate growth on a panel of different carbon or nitrogen sources.

- Gene Essentiality: For each gene in the model, simulate a knockout by setting its activity to

- In vivo Experimentation:

- Gene Knockouts: Create a library of single-gene knockout strains.

- Phenotypic Microarray: Use high-throughput growth assays (e.g., in Biolog plates) to experimentally determine the essentiality of each gene and the organism's ability to utilize different substrates.

- Validation and Model Refinement: Calculate the prediction accuracy by comparing the computational and experimental results. Discrepancies often point to incorrect GPR rules, missing transport reactions, or gaps in the metabolic network, guiding further manual curation [13].

Table 3: Example Validation Metrics for the S. radiopugnans iZDZ767 Model [13]

| Validation Type | Condition/Genes Tested | Prediction Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Source Utilization | 28 different carbon sources | 82.1% (23/28) |

| Nitrogen Source Utilization | 6 different nitrogen sources | 83.3% (5/6) |

| Gene Essentiality | Single gene knockouts | 97.6% |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Tool Name | Type | Function in GPR Research |

|---|---|---|

| GPRuler | Software Tool | Fully automated reconstruction of GPR rules from an organism name or draft model [10]. |

| COBRA Toolbox | Software Suite (MATLAB) | Industry-standard platform for constraint-based modeling, including simulation and analysis of GPR-enabled models [13]. |

| UniProt Knowledgebase | Database | Provides critical information on protein complexes and isoforms, essential for defining AND/OR logic [10] [12]. |

| Complex Portal | Database | A key resource for protein-protein interaction data and stoichiometry of complexes [10]. |

| Merlin | Software Tool | An integrated platform for genome-scale metabolic reconstruction that includes GPR assignment features [10]. |

| ModelSEED / RAVEN | Software Toolboxes | Assist in semi-automated draft model reconstructions, including the assignment of GPR associations [10] [13]. |

| Phenotypic Microarray Plates | Laboratory Consumable | High-throughput experimental validation of growth phenotypes predicted by the model [13]. |

| pyTARG Library | Software Tool (Python) | A custom library for integrating RNA-seq data into GEMs to quantify drug effects, relying on GPR rules [15]. |

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are computational frameworks that systematically simulate an organism's metabolic network by integrating gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations, stoichiometry, and compartmentalization data [16]. For model organisms such as Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the development of multiple, iterative GEMs has created a need for systematic benchmarking to guide researchers in model selection for specific applications such as metabolic engineering, drug target identification, and systems biology studies [16] [17]. This application note provides a structured comparison of key organism-specific GEMs, detailed experimental protocols for their evaluation, and essential reagent solutions to facilitate their use in research and drug development contexts.

The continuous refinement of GEMs for key organisms has resulted in models of varying scope, from comprehensive genome-scale reconstructions to streamlined, curated models optimized for specific analysis types.

1Saccharomyces cerevisiaeModels

The development of GEMs for S. cerevisiae began in 2003 with the iFF708 model and has progressed through a series of consensus models [16]. The trajectory has advanced from Yeast1 to the latest iterations, Yeast8 and Yeast9.

Table 1: Key Genome-Scale Metabolic Models for S. cerevisiae

| Model Name | Key Features | Reactions | Genes | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast8 | Base for yETFL; includes SLIME reactions; updated GPR associations [16] [18] | 3,991 | 1,149 | Generation of advanced multi-scale models; template for strain-specific models [16] |

| Yeast9 | Refined mass/charge balances; thermodynamic parameters; integrated single-cell transcriptomics [16] | Information not in search results | Information not in search results | Analysis of yeast adaptation to stress (e.g., high osmotic pressure) [16] |

| yETFL | Integrates metabolic, protein, and RNA synthesis; incorporates thermodynamic constraints & enzyme kinetics [18] | Information not in search results | 1,393 (1,149 metabolic + 244 expression system) | Prediction of growth rates, essential genes, and overflow metabolism under expression constraints [18] |

2Mycobacterium tuberculosisModels

Multiple GEMs have been constructed for M. tuberculosis strain H37Rv, derived primarily from two early reconstructions: GSMN-TB and iNJ661 [17]. A systematic evaluation of eight models identified two as top performers.

Table 2: Benchmarking of Select M. tuberculosis H37Rv GEMs

| Model Name | Precursor/Origin | Key Strengths | Notable Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| iEK1011 | Consolidated model using BiGG database standardization [17] | High gene similarity (>60%) with all other models; good performance in gene essentiality prediction [17] | Performance details not in search results |

| sMtb2018 | Combination of three previous models [17] | High gene similarity with other models; designed for modeling metabolism inside macrophages [17] | Performance details not in search results |

| iOSDD890 | Curated update of iNJ661 [17] | High coverage of nitrogen, propionate, and pyrimidine metabolism [17] | Lacks β-oxidation pathways; cannot simulate growth on fatty acids [17] |

3Escherichia coliModels

The modeling landscape for E. coli includes both genome-scale and focused, manually-curated models designed for specific analytical tasks.

Table 3: Representative E. coli K-12 MG1655 Metabolic Models

| Model Name | Scale | Reactions | Genes | Purpose and Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iML1515 | Genome-Scale | 2,712 | 1,515 | Comprehensive metabolic network; template for smaller models [19] |

| iCH360 | Medium-Scale ("Goldilocks") | 323 | 360 | Manually curated model of core energy and biosynthetic metabolism; avoids unphysiological predictions [19] |

| ECC2 | Medium-Scale | Information not in search results | Information not in search results | Algorithmically reduced model; retains ability to produce biomass precursors [19] |

Experimental Protocols for Model Evaluation and Application

Protocol: Systematic Evaluation of Multiple GEMs

This protocol is adapted from the methodology used to benchmark M. tuberculosis GEMs [17] and can be applied to evaluate models for any organism.

1. Descriptive Model Evaluation

- Objective: Compare basic structural properties and network connectivity.

- Procedure:

- Calculate and compare the number of reactions, metabolites, and genes for each model.

- Perform a set theory-based analysis to identify the core set of genes common to all models and strain-specific accessory genes [17].

- Identify and map blocked reactions (reactions that cannot carry flux under any condition) and gaps in the metabolic network.

- Output: A quantitative inventory of model components and coverage of essential pathways.

2. Assessment of Thermodynamic Feasibility

- Objective: Identify thermodynamically infeasible cycles that can lead to unrealistic flux predictions.

- Procedure:

- Output: A list of infeasible cycles and a thermodynamically curated model.

3. Phenotypic Prediction Accuracy

- Objective: Test the model's ability to recapitulate known experimental phenotypes.

- Procedure:

- Growth Simulation: Use Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to predict growth capabilities on different carbon and nitrogen sources (e.g., glucose, cholesterol for Mtb) [17].

- Gene Essentiality Prediction: Simulate single-gene knockout strains and compare the predictions of essential/non-essential genes against experimental gene essentiality data [17].

- Flux Variability Analysis (FVA): Determine the range of possible fluxes for each reaction to assess network flexibility [17].

Protocol: Constructing an Expression-Mechanics Model from a GEM

This protocol outlines the steps for building a multi-scale model like yETFL, which integrates metabolism with expression constraints [18].

1. Thermodynamic Curation of the Base GEM

- Objective: Establish a thermodynamically consistent foundation.

- Procedure:

- Obtain standard Gibbs free energies of formation (ΔfG'°) for metabolites using group contribution methods [18].

- For reactions in aqueous environments, calculate the Gibbs free energy of reaction (ΔrG'°).

- Constrain reaction directions in the model to be consistent with their calculated ΔrG'° values.

2. Integration of Enzyme Kinetics and Catalytic Constraints

- Objective: Incorporate proteomic limitations.

- Procedure:

- Compile enzyme turnover numbers (kcat) from databases and literature. Use median kcat values for enzymes with unknown kinetics [18].

- Formulate catalytic constraints that couple metabolic flux through a reaction to the abundance and catalytic capacity of its enzyme.

- Model the synthesis of enzyme complexes from their constituent peptides.

3. Implementation of the Expression Machinery

- Objective: Account for the biosynthetic costs of proteins and RNAs.

- Procedure:

- For eukaryotes like S. cerevisiae, include separate ribosomes and RNA polymerases for the nucleus and mitochondria [18].

- Define constraints that represent the cellular capacity for transcription and translation.

- Discretize the growth range (e.g., [0, μ_max]) into multiple bins to linearize the problem and enable solution via mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) [18].

Table 4: Key Reagent Solutions for GEM Construction and Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Tools/Databases |

|---|---|---|

| Reconstruction Toolboxes | Automated draft model generation from genomic data | RAVEN Toolbox [16], CarveFungi [16] |

| Constraint-Based Analysis Suites | Simulation and analysis of GEMs (FBA, FVA, etc.) | COBRApy [19] |

| Thermodynamic Databases | Estimation of Gibbs free energy for metabolites and reactions | Group Contribution Method [18] |

| Enzyme Kinetics Databases | Provision of enzyme turnover numbers (kcat) | Published literature and specialized databases [18] |

| Visualization Platforms | Creation of custom metabolic maps for model visualization | Escher [19] |

| Standardized Model Databases | Access to curated models and reactions using standardized nomenclature | BiGG Models [17] |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

GEM Evaluation and Selection Workflow

The following diagram outlines the logical process for systematically evaluating and selecting a GEM for a research project, based on the benchmarking study of M. tuberculosis models [17].

GEM Selection Workflow: This chart outlines the systematic process for evaluating and selecting a genome-scale metabolic model, from initial assembly to final application.

Multi-Scale Model Development Process

This diagram illustrates the process of enhancing a standard GEM into a multi-scale model by integrating additional layers of biological constraints, as demonstrated by the development of yETFL [18].

Multi-Scale Model Development: This flowchart shows the sequential layering of thermodynamic, enzymatic, and expression constraints onto a base GEM to create a more predictive multi-scale model.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a cornerstone mathematical approach within the constraint-based modeling framework for analyzing the flow of metabolites through metabolic networks [20]. As a computational method, it enables the prediction of steady-state metabolic fluxes in genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), which represent the entire metabolic repertoire of an organism based on its genomic annotation [9]. FBA has gained prominence as a powerful systems biology tool because it can simulate metabolism without requiring extensive kinetic parameter data, instead relying on stoichiometric constraints and optimization principles to predict cellular behavior [20] [21]. This capability makes FBA particularly valuable for harnessing the knowledge encoded in the growing number of GEMs, with models now available for thousands of organisms across bacteria, archaea, and eukarya [9].

The fundamental value of FBA lies in its ability to transform static genome-scale metabolic reconstructions into dynamic models that can predict phenotypic outcomes from genotypic information [22]. By calculating the flow of metabolites through metabolic networks, FBA enables researchers to predict critical cellular phenotypes such as growth rates, nutrient uptake rates, by-product secretion, and the metabolic consequences of genetic modifications [20] [23]. This predictive capacity has made FBA an indispensable tool in both basic research and applied biotechnology, supporting applications ranging from microbial strain engineering for industrial biotechnology to identifying novel drug targets in pathogens [21] [9] [24].

Mathematical Foundations

The mathematical framework of FBA is built upon stoichiometric constraints, mass-balance equations, and optimization theory [20]. This foundation allows FBA to systematically analyze metabolic capabilities without detailed kinetic information, instead focusing on the network structure and mass conservation principles.

Stoichiometric Matrix Representation

The core mathematical representation in FBA is the stoichiometric matrix S, of size m × n, where m represents the number of metabolites and n the number of reactions in the metabolic network [20]. Each element Sᵢⱼ of this matrix contains the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j. By convention, negative coefficients indicate metabolite consumption, positive coefficients indicate metabolite production, and zero values indicate no participation [20]. This matrix formulation comprehensively captures the structure of the metabolic network and serves as the foundation for all subsequent constraint-based analyses.

Mass Balance Constraints

The fundamental constraint in FBA is the steady-state mass balance assumption, which requires that the concentration of internal metabolites remains constant over time [20] [21]. This is mathematically represented by the equation:

S · v = 0

where v is the n-dimensional vector of metabolic reaction fluxes [20]. This equation ensures that for each metabolite in the network, the total flux producing the metabolite equals the total flux consuming it, thus maintaining constant metabolite concentrations at steady state [21]. For realistic large-scale metabolic models where the number of reactions typically exceeds the number of metabolites (n > m), this system of equations is underdetermined, meaning there is no unique solution [20].

Flux Constraints and Boundary Conditions

To make the underdetermined system tractable, FBA incorporates additional constraints on reaction fluxes:

vₗ ≤ v ≤ vᵤ

where vₗ and vᵤ represent the lower and upper bounds for each reaction flux, respectively [20]. These bounds incorporate known physiological constraints, such as:

- Irreversible reactions (v ≥ 0)

- Measured substrate uptake rates

- Thermodynamic and enzyme capacity constraints

- Environmental conditions (e.g., oxygen availability)

Objective Function and Linear Programming

FBA identifies a particular flux distribution from the possible solution space by optimizing a biologically relevant objective function [20]. The general formulation becomes:

Maximize Z = cᵀv Subject to: S · v = 0 vₗ ≤ v ≤ vᵤ

where c is a vector of weights indicating how much each reaction contributes to the objective function [20]. In practice, when maximizing a single reaction (such as biomass production), c is typically a vector of zeros with a value of 1 at the position of the reaction of interest [20]. This optimization problem is solved using linear programming, which efficiently identifies optimal solutions even for large-scale metabolic networks [20] [21].

Table 1: Key Components of the FBA Mathematical Framework

| Component | Symbol | Description | Role in FBA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Matrix | S | m × n matrix of stoichiometric coefficients | Defines network structure and mass balance constraints |

| Flux Vector | v | n-dimensional vector of reaction fluxes | Variables to be solved representing metabolic reaction rates |

| Mass Balance | S·v = 0 | System of linear equations | Ensures metabolic steady state |

| Flux Bounds | vₗ, vᵤ | Lower and upper flux constraints | Incorporates physiological and environmental limitations |

| Objective Function | Z = cᵀv | Linear combination of fluxes | Defines biological objective to be optimized |

Computational Implementation

Core Protocol for Flux Balance Analysis

The standard workflow for implementing FBA consists of five key steps that transform a metabolic reconstruction into a predictive model:

Step 1: Model Construction and Curation

- Compile a stoichiometrically balanced metabolic network reconstruction including all known metabolic reactions, metabolites, and gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations [9]

- Verify mass and charge balance for all reactions

- Define metabolic compartments (for eukaryotic organisms) and transport reactions

Step 2: Define Environmental Constraints

- Specify nutrient availability in the growth medium by setting upper bounds on exchange reactions [20]

- Constrain oxygen uptake rates for aerobic/anaerobic simulations [20]

- Set constraints on by-product secretion based on experimental measurements

Step 3: Formulate the Objective Function

- Select an appropriate biological objective based on the research question [20]

- Common objectives include:

- Biomass maximization (for growth prediction)

- ATP production (for energy metabolism studies)

- Product synthesis (for metabolic engineering)

- Nutrient uptake optimization

Step 4: Solve the Linear Programming Problem

- Apply linear programming algorithms to maximize/minimize the objective function [20]

- Verify solution feasibility and optimality

- Extract the flux distribution vector v corresponding to the optimal solution

Step 5: Validate and Interpret Results

- Compare predictions with experimental data (growth rates, substrate uptake, by-product secretion) [20]

- Perform sensitivity analysis to assess robustness of predictions

- Identify key metabolic pathways contributing to the objective

Advanced FBA Variants

Several extended FBA methodologies have been developed to address specific biological questions and overcome limitations of the standard approach:

Metabolite Dilution FBA (MD-FBA) MD-FBA accounts for growth-associated dilution of all intermediate metabolites, not just those included in the biomass reaction [23]. This is particularly important for metabolites participating in catalytic cycles, such as metabolic co-factors, and improves predictions of gene essentiality and growth rates under different conditions [23]. MD-FBA is formulated as a mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) problem to handle the discrete decisions involved in accounting for dilution of all produced metabolites.

Dynamic FBA (dFBA) dFBA extends the steady-state approach to dynamic conditions by solving a series of FBA problems over time, incorporating changing extracellular metabolite concentrations and using the predicted growth rates to update these concentrations at each time step [22].

Regulatory FBA (rFBA) rFBA incorporates transcriptional regulatory constraints by integrating Boolean logic rules based on gene expression states, thereby constraining reaction activity based on regulatory information in addition to stoichiometric constraints [25].

Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) FVA identifies the range of possible fluxes for each reaction while maintaining optimal or near-optimal objective function values, addressing the issue of multiple optimal solutions in FBA [20].

Table 2: Computational Tools for Flux Balance Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox [20] | MATLAB-based suite for constraint-based analysis | Comprehensive implementation of FBA and related methods; support for SBML models | General metabolic modeling, gene essentiality analysis |

| ModelSEED [26] | Web-based model reconstruction and analysis | Automated pipeline for generating GEMs from genome annotations | Rapid model construction, gap-filling |

| CarveMe [26] | Automated model reconstruction | Top-down approach using core metabolic model; diamond-based gap-filling | High-throughput model building |

| RAVEN [26] | MATLAB-based reconstruction and analysis | Integration with KEGG and MetaCyc; manual curation interface | Eukaryotic model reconstruction, yeast metabolism |

| OptFlux [21] | Metabolic engineering platform | Strain design algorithms; visualization capabilities | Metabolic engineering, knockout prediction |

Applications in Metabolic Research

Prediction of Growth Phenotypes

FBA enables accurate prediction of microbial growth rates under various genetic and environmental conditions [20]. For example, FBA predictions of E. coli growth under aerobic (1.65 hr⁻¹) and anaerobic (0.47 hr⁻¹) conditions with glucose limitation have shown strong agreement with experimental measurements [20]. The protocol for growth prediction involves:

- Constraining the glucose uptake rate to a physiologically realistic level (e.g., 18.5 mmol gDW⁻¹ hr⁻¹)

- Setting appropriate oxygen uptake constraints (high for aerobic, zero for anaerobic)

- Maximizing the flux through the biomass objective function

- Comparing the predicted growth rate with experimental data

Gene Essentiality and Knockout Analysis

FBA can systematically identify essential metabolic genes by simulating the effect of gene deletions [20] [21]. The standard protocol involves:

- For each gene in the model, constrain the flux through all associated reactions to zero based on GPR rules

- Re-optimize the biomass objective function

- Classify genes as essential if the predicted growth rate falls below a threshold (typically 1-5% of wild-type)

- Validate predictions against experimental knockout data

This approach has been extended to double gene knockout analysis, enabling identification of synthetic lethal interactions [20]. For example, FBA has been used to explore all pairwise combinations of 136 E. coli genes to identify double knockouts that are lethal despite single knockouts being viable [20].

Metabolic Engineering and Strain Design

FBA supports rational design of microbial strains for industrial biotechnology by predicting genetic modifications that enhance product yields [21] [9]. Algorithms such as OptKnock use FBA to identify gene deletion strategies that couple desired product formation with growth [20] [21]. The implementation protocol includes:

- Formulating a bi-level optimization problem that maximizes product formation while maintaining growth

- Using mixed-integer linear programming to identify optimal gene knockouts

- Validating predicted strain designs experimentally

- Applications include production of biofuels, organic acids, and pharmaceutical precursors

Host-Microbe Interactions

FBA enables modeling of metabolic interactions between hosts and their associated microbiota [26]. The protocol for constructing host-microbe metabolic models involves:

- Reconstructing or retrieving individual GEMs for host and microbial species

- Integrating models into a unified framework using standardized metabolite nomenclature

- Defining metabolite exchange between host and microbial compartments

- Simulating the integrated system to predict metabolic cross-feeding and dependencies

This approach has been applied to study host-pathogen interactions, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis in alveolar macrophages [9], and to understand the role of gut microbiota in human health and disease [26].

Visualization of FBA Workflow

Diagram 1: FBA Workflow from Reconstruction to Prediction

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for FBA Implementation

| Resource Type | Specific Tools/Databases | Function in FBA Research |

|---|---|---|

| Model Databases | BiGG [26], AGORA [26], MetaNetX [26] | Provide curated metabolic models for various organisms |

| Reconstruction Tools | ModelSEED [26], CarveMe [26], RAVEN [26] | Automate generation of draft GEMs from genomic data |

| Simulation Software | COBRA Toolbox [20], OptFlux [21], COBRApy | Implement FBA algorithms and related methods |

| Linear Programming Solvers | Gurobi, CPLEX, GLPK [26] | Provide optimization algorithms for solving LP problems |

| Model Standards | SBML [20], SMBL-ML | Enable model exchange and interoperability between tools |

| Organism-Specific Models | iML1515 (E. coli) [9], Yeast8 (S. cerevisiae) [9], Recon3D (Human) [26] | Provide high-quality reference models for key organisms |

Protocol for Gene Essentiality Prediction

The following detailed protocol outlines the steps for predicting gene essentiality using FBA, a fundamental application in metabolic network analysis:

Step 1: Model Preparation

- Load the genome-scale metabolic model (in SBML format) using the

readCbModelfunction in the COBRA Toolbox [20] - Verify model quality by checking for mass and charge balance violations

- Set baseline constraints to define the simulated growth condition:

- Carbon source uptake (e.g., glucose: 10 mmol/gDW/hr)

- Oxygen uptake (20 mmol/gDW/hr for aerobic conditions)

- Other essential nutrients (N, P, S sources)

Step 2: Wild-Type Reference Simulation

- Maximize biomass production using

optimizeCbModelfunction [20] - Record the wild-type growth rate (μ_wt) as reference

- Validate that the predicted growth rate is physiologically reasonable

Step 3: Gene Deletion Simulation

- For each gene i in the model:

- Identify all reactions associated with gene i using GPR rules

- Constrain fluxes through these reactions to zero using

changeRxnBounds[20] - Re-optimize biomass production

- Record the mutant growth rate (μ_mut)

- End loop

Step 4: Essentiality Classification

- For each gene i:

- Calculate growth ratio: GR = μmut / μwt

- Classify based on threshold:

- Essential: GR < 0.01 (or < 1% of wild-type)

- Non-essential: GR ≥ 0.01

- End loop

Step 5: Validation and Analysis

- Compare predictions with experimental essentiality data

- Calculate accuracy metrics: precision, recall, F1-score

- Identify false predictions for model refinement

This protocol has been successfully applied to predict gene essentiality in E. coli under various conditions, showing high agreement with experimental results [20] [9].

Limitations and Future Directions

While FBA is a powerful approach, it has several limitations that active research seeks to address:

Key Limitations:

- Assumes steady-state metabolism, neglecting dynamic transitions [20]

- Does not inherently account for metabolic regulation or enzyme kinetics [20]

- Relies on accurate biomass composition data, which may vary across conditions [23]

- May predict biologically unrealistic flux distributions due to omission of metabolite dilution effects [23]

Emerging Solutions:

- Integration with machine learning approaches to incorporate omics data [22]

- Development of methods like MD-FBA that account for metabolite dilution [23]

- Incorporation of thermodynamic constraints to eliminate infeasible cycles [9]

- Multi-scale models that integrate metabolic, regulatory, and signaling networks [25]

Future developments in FBA will likely focus on enhancing predictive accuracy through better integration of multi-omics data, improving handling of dynamic conditions, and expanding applications to complex microbial communities and host-pathogen systems [22] [26] [9]. As metabolic reconstructions continue to improve in quality and coverage, FBA will remain an essential computational tool for translating genomic information into predictive metabolic models.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are comprehensive computational representations of the metabolic networks within an organism. They define the biochemical relationships between genes, proteins, and reactions (GPR associations) for all metabolic genes in a genome, enabling mathematical simulation of metabolic fluxes using techniques like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [9]. Since the first GEM for Haemophilus influenzae was reconstructed in 1999, the field has expanded dramatically, with models now spanning diverse organisms across all domains of cellular life [9]. GEMs have evolved into indispensable platforms for integrating various omics data (e.g., genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics) and for systems-level studies of metabolism, with applications ranging from biotechnology to medicine [22].

The value of GEMs lies in their ability to contextualize different types of biological "Big Data" within a structured metabolic network. They quantitatively link genotype to phenotype by simulating the flow of metabolites through the entire metabolic network, allowing researchers to predict an organism's metabolic capabilities and physiological states under different conditions [22]. This review provides a detailed analysis of the current coverage of GEMs across the bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic domains, and presents standardized protocols for their construction and application.

Current Status of GEM Coverage Across Life Domains

As of February 2019, GEMs have been reconstructed for 6,239 organisms across the three domains of life, demonstrating extensive coverage of metabolic diversity [9]. The distribution is heavily skewed toward bacteria, which account for the majority of reconstructed models. The table below summarizes the quantitative distribution of GEM coverage.

Table 1: Current GEM Coverage Across Life Domains (as of February 2019)

| Domain | Number of Organisms with GEMs | Number with Manual GEM Reconstruction |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | 5,897 | 113 |

| Archaea | 127 | 10 |

| Eukarya | 215 | 60 |

| Total | 6,239 | 183 |

Notably, only a small fraction of these models (183 out of 6,239) have been manually reconstructed, highlighting that most GEMs are generated through automated reconstruction tools. The manually curated models typically represent scientifically, industrially, or medically important organisms and are generally of higher quality, with more accurate gene-protein-reaction associations and better predictive capabilities [9].

GEM Coverage in Bacteria

Bacteria represent the most extensively modeled domain, with thousands of GEMs reconstructed. High-quality, manually curated models have been developed for several key model organisms, which serve as references for developing GEMs for related species [9].

- Escherichia coli: As a fundamental model organism, E. coli has a well-established history of GEM development. The most recent model, iML1515, contains 1,515 open reading frames and demonstrates 93.4% accuracy in predicting gene essentiality under minimal media with different carbon sources [9]. Specialized versions have been created for specific applications, such as iML1515-ROS for studying reactive oxygen species and antibiotic design.

- Bacillus subtilis: Several GEMs exist for this Gram-positive bacterium, important in industrial biotechnology. The latest model, iBsu1144, incorporates thermodynamic information to improve the accuracy of reaction reversibility [9].

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis: GEMs of this human pathogen, such as iEK1101, have been used to study its metabolism under different conditions relevant to its disease-causing state, aiding in drug target identification [9].

- Streptococcus suis: A recent GEM for this zoonotic pathogen, iNX525, includes 525 genes, 708 metabolites, and 818 reactions. It has been used to analyze virulence factors and identify potential antimicrobial targets by evaluating genes essential for both growth and virulence [2].

A significant advancement in bacterial GEMs is the development of multi-strain models, which help understand metabolic diversity within a species. For example, a multi-strain GEM was created from 55 individual E. coli models, comprising a "core" model (intersection of all models) and a "pan" model (union of all models) [22]. Similar approaches have been applied to Salmonella (410 strains), Staphylococcus aureus (64 strains), and Klebsiella pneumoniae (22 strains) [22].

GEM Coverage in Archaea

Archaea are the least represented domain in terms of GEM coverage, with only nine available models reported in recent literature [22]. This limited representation reflects the challenges in studying these organisms, many of which inhabit extreme environments.

- Methanosarcina acetivorans: This methanogenic archaeon is among the best-studied archaeal species with GEMs. The iMAC868 model was curated to represent a thermodynamically feasible methanogenesis reversal pathway [9]. Another model, iST807, incorporated tRNA-charging reactions to characterize the effects of differential tRNA gene expression on metabolic fluxes [9].

- Methanobacterium formicicum: This methanogen, present in the digestive systems of humans and ruminants, has a GEM that has been used to study its role in gastrointestinal and metabolic disorders [22].

Archaea possess distinct molecular characteristics and exotic metabolisms, such as methanogenesis, making their GEMs valuable resources for understanding life in extreme environments and for exploring novel enzymatic capabilities [22].

GEM Coverage in Eukarya

Eukaryotic GEMs cover a diverse range of organisms, including fungi, plants, and animals.

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae: The baker's yeast was the first eukaryote to have a GEM reconstructed. Its models have undergone extensive refinement through international collaborative efforts. The latest version, Yeast 7, incorporates new biological information and corrects thermodynamic inaccuracies from earlier versions [9].

- Homo sapiens: Human GEMs have been reconstructed and used to study human diseases and host-pathogen interactions. For instance, a GEM of Mycobacterium tuberculosis has been integrated with a GEM of human alveolar macrophages to study the metabolic interactions during infection [9].

Diagram: GEM coverage is distributed across the three domains of life, with bacteria representing the majority of reconstructed models. High-quality, manually curated models exist for key organisms within each domain.

Protocols for GEM Reconstruction and Validation

The reconstruction of a high-quality GEM is a multi-step process that integrates genomic, biochemical, and physiological data. The following protocol, synthesized from current methodologies, outlines the key stages for manual reconstruction and validation of a GEM.

Protocol 1: Draft Model Reconstruction

Objective: To generate a draft metabolic network from genomic annotations.

Materials and Reagents:

- Genome Annotation Data: Annotated genome sequence of the target organism (e.g., from RAST or Prokka) [2].

- Template Models: Existing high-quality GEMs of phylogenetically related organisms (e.g., for S. suis, models of B. subtilis, S. aureus, and S. pyogenes were used) [2].

- Biochemical Databases: KEGG, MetaCyc, BioCyc, and UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot for reaction and enzyme information [2].

- Bioinformatics Tools: BLAST software for sequence comparison [2].

- Computational Environment: COBRA Toolbox in MATLAB or Python for model simulation and analysis [2].

Procedure:

- Automated Draft Construction: Input the annotated genome into an automated reconstruction platform like ModelSEED to generate an initial draft model [2].

- Manual Curation via Homology: Identify gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations from template models. Use BLAST to find homologous genes in the target organism (criteria: identity ≥ 40%, match lengths ≥ 70%) and transfer associated reactions [2].

- Data Integration: Manually integrate the GPR lists from the automated and homology-based methods into a single draft model, unifying reaction equations and identifiers [2].

- Gap Analysis: Use the

gapAnalysisfunction in the COBRA Toolbox to identify metabolic gaps—reactions that are necessary to produce key biomass precursors but are missing in the network [2]. - Gap Filling: Manually fill gaps by adding relevant reactions based on literature evidence, transporter data from the Transporter Classification Database (TCDB), and new gene function assignments via BLASTp against UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot [2].

- Mass and Charge Balance: Refine the model by ensuring all reactions are stoichiometrically balanced for mass and charge. Use the

checkMassChargeBalanceprogram to identify unbalanced reactions and add missing metabolites (e.g., H₂O, H⁺, CO₂) as necessary [2].

Protocol 2: Biomass Composition Formulation

Objective: To define the biomass objective function, which represents the metabolic requirements for cell growth.

Materials and Reagents:

- Experimental Data: Literature data on the macromolecular composition (proteins, DNA, RNA, lipids, etc.) of the target organism or a closely related species [2].

- Genomic and Proteomic Data: The organism's genome and protein sequences to calculate nucleotide and amino acid compositions [2].

Procedure:

- Adopt a Reference Composition: If the target organism's composition is unknown, adopt the composition from a phylogenetically close model. For example, the S. suis biomass composition was based on that of Lactococcus lactis [2].

- Define Macromolecular Fractions: Determine the dry weight fractions of major cellular components. The S. suis model includes: proteins (46%), DNA (2.3%), RNA (10.7%), lipids (3.4%), lipoteichoic acids (8%), peptidoglycan (11.8%), capsular polysaccharides (12%), and cofactors (5.8%) [2].

- Specify Building Blocks: Calculate the precise molar contributions of metabolites (e.g., individual amino acids for protein, nucleotides for DNA and RNA) based on the organism's genomic and proteomic sequences [2].

- Formulate the Equation: Assemble the biomass reaction as a weighted sum of all required metabolites, scaled to produce one gram of biomass [2].

Protocol 3: Model Validation and Phenotypic Prediction

Objective: To test and refine the model by comparing its predictions with experimental data.

Materials and Reagents:

- Validated GEM: The reconstructed model from Protocol 1 and 2.

- Physiological Data: Experimental data on growth capabilities under different nutrient conditions and gene essentiality data from mutant screens [2].

- Computational Solver: A mathematical optimization solver like GUROBI called via the COBRA Toolbox [2].

Procedure:

- Simulate Growth Phenotypes: Use Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) with the biomass reaction as the objective function. Constrain the model to simulate a defined growth medium (e.g., a chemically defined medium - CDM) and predict growth rates [2].

- "Leave-One-Out" Experiments: Systematically omit specific nutrients (e.g., amino acids, vitamins) from the simulated medium and predict whether growth is still possible. Compare these predictions with experimental growth assays [2].

- Gene Essentiality Prediction: For each gene in the model, simulate a gene knockout by setting the flux of its associated reaction(s) to zero. A gene is predicted as essential if the knockout leads to a severe growth impairment (e.g., growth ratio < 0.01 of the wild-type) [2].

- Model Refinement: Iteratively refine the model (by adjusting GPRs, adding transporters, or correcting network connectivity) to improve the agreement between computational predictions and experimental observations. The S. suis iNX525 model showed 71.6% to 79.6% agreement with gene essentiality screens [2].

Diagram: The standard workflow for reconstructing and validating a genome-scale metabolic model involves an iterative process of draft construction, biomass formulation, and experimental validation.

Application Notes: Utilizing GEMs for Metabolic Insights

Application Note 1: Identification of Virulence-Linked Metabolic Targets

Background: Understanding the link between metabolism and virulence is crucial for combating bacterial pathogens. GEMs can systematically identify metabolic genes that are essential for both growth and the production of virulence factors (VFs).

Methodology:

- VF Gene Mapping: Identify metabolic genes associated with virulence by comparing the model's gene set against virulence factor databases [2].

- Simulation of VF Formation: For each virulence-linked metabolite (e.g., components of capsular polysaccharides or peptidoglycans), set its "demand" reaction as the objective function in an FBA simulation [2].

- Dual-Essentiality Analysis: Perform in silico gene knockout simulations with two objective functions: a) biomass production and b) production of a specific VF. Genes whose knockout disrupts both objectives are considered dual-essential [2].

Results and Interpretation: In the S. suis iNX525 model, 131 virulence-linked genes were identified, 79 of which were associated with 167 metabolic reactions in the model [2]. A total of 26 genes were found to be essential for both cell growth and virulence factor production. Enzymes and metabolites involved in the biosynthesis of capsular polysaccharides and peptidoglycans were highlighted as high-priority targets for antibacterial drug development, as inhibiting them would simultaneously compromise bacterial growth and pathogenicity [2].

Application Note 2: Multi-Strain and Pan-Reactome Analysis

Background: Genomic variation between strains of the same species can lead to differences in metabolic capabilities and virulence. Multi-strain GEMs, or pan-reactomes, allow for a comparative analysis of this metabolic diversity.

Methodology:

- Construct Individual GEMs: Reconstruct a GEM for each strain in a collection using a consistent methodology [22].