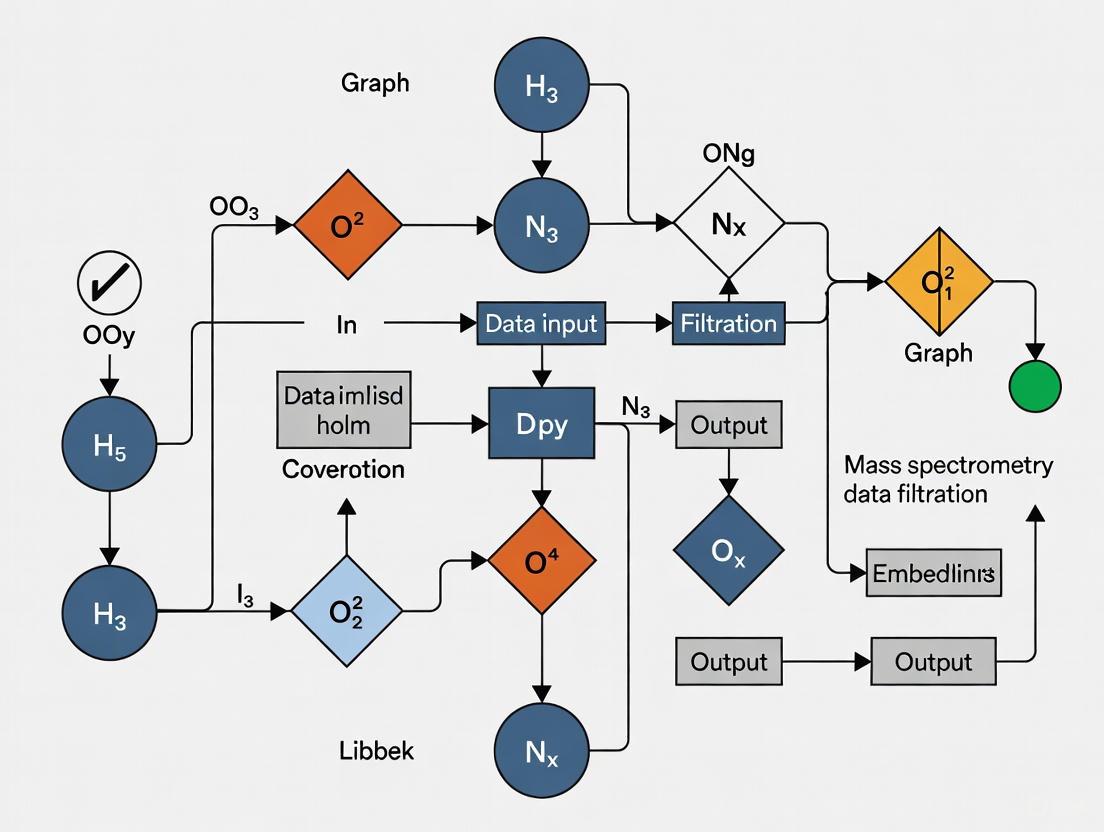

Graph Embedding for Mass Spectrometry Data Filtration: A Revolutionary Approach for Enhanced Metabolomic Analysis

This article explores the transformative potential of graph embedding techniques for filtering and analyzing complex mass spectrometry (MS) data, particularly in untargeted metabolomics.

Graph Embedding for Mass Spectrometry Data Filtration: A Revolutionary Approach for Enhanced Metabolomic Analysis

Abstract

This article explores the transformative potential of graph embedding techniques for filtering and analyzing complex mass spectrometry (MS) data, particularly in untargeted metabolomics. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive guide from foundational concepts to advanced applications. We detail how methods like Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) overcome the limitations of traditional statistical filtration, which often overfilters and discards biologically relevant signals. The scope includes practical methodologies, troubleshooting for scalability and interpretability, and a comparative analysis of emerging tools like GEMNA. The article concludes by synthesizing key takeaways and outlining future directions for integrating these approaches into biomedical and clinical research pipelines to accelerate discovery.

Beyond Traditional Filters: Why Graph Embeddings are Revolutionizing MS Data Preprocessing

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Low Annotation Rates in Non-Targeted Screening

Problem: Despite acquiring high-resolution MS/MS data, a large proportion of chemical features in your non-targeted screening (NTS) study remain unidentified.

Solution: Implement a multi-strategy prioritization framework to focus identification efforts on the most relevant, high-quality signals [1].

Step 1: Apply Data Quality Filtering Use algorithms like the Dynamic Noise Level (DNL) to distinguish signal peaks from noise. The DNL algorithm scans peaks from lowest to highest abundance, using linear regression on previously identified noise peaks to predict the next peak's abundance. A peak is classified as signal if its Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR = Observed Abundance / Predicted Abundance) exceeds a threshold (typically SNR ≥ 2). Spectra with fewer than a minimum number of signal peaks (e.g., n < 8) are filtered out [2].

Step 2: Chemistry-Driven Prioritization Leverage high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) data properties to flag ions of interest. Prioritize features indicative of halogenated compounds (based on isotopic patterns), potential transformation products, or compounds containing specific elements [1].

Step 3: Process-Driven Comparison Use spatial, temporal, or process-based comparisons (e.g., pre- vs. post-treatment, case vs. control) to identify features that show significant variation. Techniques like Analysis of Variance Simultaneous Component Analysis (ASCA) can quantify these effects and highlight relevant features [3].

Step 4: Advanced Spectral Matching Move beyond traditional cosine similarity. Employ modern embedding-based matching algorithms like Spec2Vec or LLM4MS, which capture deeper spectral relationships. LLM4MS, which uses large language models, has been shown to improve Recall@1 accuracy by 13.7% over Spec2Vec [4].

Guide 2: Mitigating Workflow-Induced Variability in Feature Detection

Problem: Downstream chemical interpretation changes significantly depending on whether you use a feature profile (FP) package like MZmine3 or a component profile (CP) approach like ROIMCR.

Solution: Understand the inherent biases of each workflow and use them complementarily [3].

Step 1: Profile Selection

- FP-based (e.g., MZmine3): More sensitive to treatment effects but potentially more susceptible to false positives. Use when your goal is to detect as many potential markers as possible.

- CP-based (e.g., ROIMCR): Provides superior consistency, reproducibility, and clarity for temporal dynamics, but may have lower treatment sensitivity. Ideal for tracking changes over time or when high reproducibility is critical.

Step 2: Cross-Validation with Chemometrics Apply multivariate statistical methods like Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) to both workflows. Features that are consistently prioritized by both FP and CP approaches, and that have high discriminatory power in PLS-DA models, are high-confidence candidates for identification [3].

Step 3: Integrative Analysis Combine results from both workflows to obtain a more holistic view of the chemical space. This complementary use can help counterbalance the limitations of each individual method [3].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Our statistical filtering seems to remove too many features, potentially losing biologically relevant signals. What are our options?

Traditional statistical filters (e.g., ANOVA, t-test) can be overly aggressive. Consider a graph embedding approach like GEMNA (Graph Embedding-based Metabolomics Network Analysis). This method uses node and edge embeddings powered by Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to analyze MS data. It filters data based on the structure of metabolic networks rather than isolated p-values, which can preserve relevant features that would otherwise be lost. In one study, GEMNA achieved a silhouette score of 0.409, significantly outperforming a traditional approach that scored -0.004, demonstrating its superior ability to form meaningful clusters without overfiltering [5].

FAQ 2: How can I visualize complex, multimodal MS data to improve my interpretation and quality control?

Use integrative visualization frameworks like Vitessce. This web-based tool allows for the coordinated visualization of multimodal data (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics, images) alongside MS-based results. You can create linked views between scatterplots of your metabolic features, spatial data, and other omics layers, enabling you to visually identify correlations and patterns that might be missed in separate analyses. It is scalable to millions of data points and can be integrated into Jupyter Notebooks or RStudio for seamless analysis [6].

FAQ 3: We need deeper structural information for confident compound identification, but MS² is not sufficient. What is the next step?

Pursue multi-stage fragmentation (MSⁿ). MSⁿ generates spectral trees that provide deeper structural insights into substructures and help validate fragmentation pathways, which is crucial for distinguishing isomers. While public MSⁿ libraries have been limited, new open resources like MSnLib are now available. MSnLib contains over 2.3 million MSⁿ spectra for 30,008 unique small molecules, providing a vast reference for matching and advancing machine learning models for structure prediction [7].

FAQ 4: What are graph embeddings, and how can they specifically help with my MS data filtration problem?

Graph embedding is a technique that converts complex graph data (like networks of correlated metabolites) into a lower-dimensional vector space while preserving the graph's topology and properties [8]. In MS, your data can be represented as a graph where nodes are metabolites and edges are correlations or biochemical reactions. Graph embedding models like Node2Vec or GNNs can:

- Compress high-dimensional, noisy MS trajectories into tabular formats suitable for machine learning [9].

- Filter data by learning to distinguish "real" signal patterns from noise based on the network context, reducing the risk of overfiltering inherent in traditional statistics [5].

- Identify anomalous changes in metabolic networks between sample groups by analyzing the embedded representations [5].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Data Processing Workflows and Tools

This table summarizes key performance metrics and characteristics of different software and algorithms used in mass spectrometry data analysis.

| Tool / Algorithm | Type / Method | Key Performance Metric | Key Characteristic / Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| MZmine3 [3] | Feature Profile (FP) Workflow | - | Increased sensitivity to treatment effects; susceptible to false positives. |

| ROIMCR [3] | Component Profile (CP) Workflow | - | Superior consistency & temporal clarity; lower treatment sensitivity. |

| GEMNA [5] | Graph Embedding for Filtration | Silhouette Score: 0.409 (vs. -0.004 for traditional) | Identifies metabolic changes using GNNs; resists overfiltering. |

| LLM4MS [4] | Spectral Matching (LLM Embedding) | Recall@1: 66.3% (13.7% improvement vs. Spec2Vec) | Leverages chemical knowledge in LLMs for accurate matching. |

| Spec2Vec [4] | Spectral Matching (Word Embedding) | Recall@1: ~52.6% (baseline) | Captures intrinsic structural similarities between spectra. |

| DNL Algorithm [2] | Spectral Noise Filtering | Filtered 89.0% of unidentified spectra; lost 6.0% of true positives. | Dynamically determines noise level for each spectrum. |

Detailed Methodology: Graph Embedding for Metabolomic Network Analysis (GEMNA)

Purpose: To filter MS data and identify changes in metabolic networks between sample groups using graph embeddings, minimizing the loss of relevant signals [5].

Input: MS data from flow injection or chromatography-coupled systems.

Procedure:

- Network Construction: Create a metabolic network graph where nodes represent detected ions (features) and edges represent strong correlations or potential biochemical relationships between them.

- Graph Embedding Generation: Apply a Graph Neural Network (GNN) model to the network. The GNN uses a "message-passing" mechanism to learn a low-dimensional vector representation (embedding) for each node. This embedding encapsulates both the node's own features and the structural information of its neighborhood.

- Embedding-based Filtration: Use an anomaly detection algorithm on the generated node embeddings to identify and filter out nodes whose embedding patterns are inconsistent with biologically plausible signal structures.

- Differential Analysis: Compare the embedded representations of the filtered networks from different sample groups (e.g., control vs. treated) to identify sub-networks and metabolites that have undergone significant changes.

Output: A filtered MS-based signal list and a dashboard of graphs visualizing metabolic changes between samples [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Software for Advanced MS Data Analysis

A list of key software tools and data resources for implementing the strategies discussed in this guide.

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| MZmine3 [3] | Software | Flexible, open-source platform for non-targeted screening data processing (FP approach). |

| MSnLib [7] | Data Resource | Open, large-scale library of MSⁿ spectra for deeper structural annotation and validation. |

| GEMNA [5] | Software Toolbox | A deep learning toolbox for filtering MS data and analyzing metabolic changes using graph embeddings. |

| LLM4MS [4] | Algorithm | Generates discriminative spectral embeddings using fine-tuned LLMs for highly accurate compound identification. |

| Vitessce [6] | Visualization Framework | Integrative, web-based tool for visual exploration of multimodal and spatially resolved data. |

| MDGraphEmb [9] | Python Library | Converts molecular dynamics simulation trajectories into graph embeddings for analysis. |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

Graph Embedding MS Filtration

FP vs CP Workflow Comparison

What is Graph Embedding? Translating Nodes and Edges into a Vector Space

FAQs: Core Concepts

What is graph embedding in simple terms? Graph embedding is the process of translating the complex, relational structure of a graph—comprising nodes (entities) and edges (relationships)—into a lower-dimensional vector space [10]. Imagine creating a map of a graph; each "city" (node) is assigned a set of coordinates (a vector) such that cities connected by "roads" (edges) or that are part of the same "region" are located close together on the map [10]. This vector representation captures the graph's structural information and makes it digestible for machine learning algorithms.

Why is graph embedding crucial for biomedical data analysis? Biological data, such as protein-protein interaction networks or metabolic pathways, is naturally represented as graphs [8]. However, visual inspection of these complex graphs is challenging. Graph embedding techniques help by converting these graphs into a matrix of vectors, allowing researchers to better identify and quantify interactions between different biological elements, which is essential for tasks like predicting new drug functions or understanding cellular processes [8].

What's the difference between a homogeneous and a heterogeneous graph?

- Homogeneous graphs contain nodes and edges that are all of the same type. An example is a protein-protein interaction network where every node represents a protein, and every edge represents an interaction [8].

- Heterogeneous graphs contain nodes and/or edges of different types. A knowledge graph linking drugs, diseases, and genes is a classic example, as it contains multiple entity and relationship types [8] [11].

FAQs: Methods & Techniques

What are the main categories of graph embedding techniques? Graph embedding methods can be broadly classified into several categories [8] [10]:

- Random Walk-Based (e.g., DeepWalk, Node2Vec): These methods generate sequences of nodes by performing random walks on the graph. These sequences are then processed using techniques inspired by word embedding in natural language processing (like Word2Vec) to learn node embeddings. Node2Vec improves on DeepWalk by using a biased random walk that provides more control over the exploration of the network, balancing between discovering nodes that are close together (homophily) and nodes that perform similar structural roles (structural equivalence) [10].

- Matrix Factorization-Based: These techniques rely on the matrix representation of a graph (e.g., the adjacency matrix) and factorize it to obtain a lower-dimensional vector representation [8].

- Deep Learning-Based (e.g., Graph Neural Networks - GNNs): Models like GraphSAGE learn an aggregation function to generate node embeddings by sampling and combining features from a node's local neighborhood. This approach is inductive, meaning it can generate embeddings for new, unseen nodes without retraining the entire model [10] [12].

What are Translational Distance Models in Knowledge Graph Embedding?

These models treat relationships as translation operations in the vector space. The most famous example, TransE, operates on a simple but powerful principle: for a true triple (head, relation, tail), the embedding of the head entity plus the embedding of the relation should be approximately equal to the embedding of the tail entity (h + r ≈ t) [13]. This makes it computationally efficient and useful for tasks like link prediction.

How do Semantic Matching Models differ?

Semantic matching models evaluate the plausibility of a triple (h, r, t) based on the similarity of their latent representations. DistMult is a popular model that uses a simple multiplicative scoring function, but it assumes all relations are symmetric. ComplEx extends DistMult into the complex number space, enabling it to handle asymmetric relations more effectively [13].

FAQs: Applications in Biomedicine & Mass Spectrometry

How is graph embedding used in drug repositioning?

Drug repositioning aims to find new therapeutic uses for existing drugs. Knowledge graph embedding models integrate multi-source data (e.g., drugs, diseases, genes, proteins) into a cohesive network [14] [11]. By learning embeddings for all entities, these models can predict new (Drug, "Treatment", Disease) links. For example, a model was validated using COVID-19 data and successfully identified clinically approved drugs for its treatment, demonstrating the method's high accuracy and potential for accelerating drug development [14].

Can graph embedding help identify compounds in mass spectrometry data? Yes. Advanced methods like LLM4MS now leverage large language models to generate highly discriminative spectral embeddings [4]. This approach incorporates chemical expert knowledge, allowing for more accurate matching of experimental mass spectra against vast reference libraries. In evaluations, LLM4MS significantly outperformed state-of-the-art methods like Spec2Vec, achieving a Recall@1 accuracy of 66.3% (a 13.7% improvement) and enabling ultra-fast matching at nearly 15,000 queries per second [4].

What is a realistic way to evaluate a graph embedding model for predicting drug-drug interactions (DDIs)? Traditional cross-validation can lead to over-optimistic results due to data leakage. For a realistic assessment, disjoint cross-validation schemes are recommended [15]:

- Drug-wise disjoint CV: Evaluates the model's ability to predict interactions for completely new drugs that have no known interactions in the training data.

- Pairwise disjoint CV: A more challenging test that evaluates predictions for pairs of drugs where neither drug appears in the training data. These settings produce lower but more realistic performance scores, giving a true measure of the model's predictive power for novel discoveries [15].

FAQs: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

My embedding model performs well in training but poorly in predicting new, unseen nodes. What could be wrong? This is a classic sign of a transductive model limitation. Early algorithms like DeepWalk and Node2Vec are transductive, meaning they can only generate embeddings for nodes that were present during the training phase [10]. If your graph evolves and new nodes are added, you must retrain the entire model. For scenarios involving new data, consider using an inductive model like GraphSAGE, which learns a function to generate embeddings based on a node's features and neighborhood, allowing it to generalize to unseen nodes [10] [12].

How can I handle the uncertainty of relationships derived from biomedical literature? Biomedical knowledge graphs built from literature (e.g., the Global Network of Biomedical Relationships - GNBR) often have associated confidence scores for each relationship [11]. To leverage this, you can use an uncertain knowledge graph embedding method. This approach incorporates these confidence scores directly into the training objective, ensuring that the learned embeddings reflect the strength of the supporting evidence. The model is trained to minimize the difference between its prediction and the literature-derived support score for each triple [11].

My knowledge graph has complex, one-to-many relationships, and a simple TransE model is performing poorly. What are my options?

The TransE model struggles with complex relationship types like one-to-many. For instance, if a single drug D treats multiple diseases (D, treats, A) and (D, treats, B), TransE will have difficulty placing D + treats close to both A and B [13]. You should consider more advanced models designed for this:

- TransH allows an entity to have different representations when involved in different relations by projecting entities onto a relation-specific hyperplane.

- TransR introduces separate projection spaces for each relation, offering more flexibility.

- Semantic matching models like ComplEx are also well-suited for handling asymmetric relations [13].

Performance Comparison of Graph Embedding Techniques

The table below summarizes quantitative data from evaluations of different graph embedding methods in various biomedical applications.

| Application Area | Method / Model | Key Performance Metric | Reported Result | Comparative Baseline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Identification (MS) [4] | LLM4MS | Recall@1 | 66.3% | Spec2Vec (52.6%) |

| Recall@10 | 92.7% | - | ||

| Drug Repositioning (COVID-19) [14] | Attentive KGE Models | Clinical Validation | Identified 7 approved drugs | Clinical trial data |

| Drug-Drug Interaction (DDI) Prediction [15] | RDF2Vec (Skip-Gram) | AUC (Traditional CV) | 0.93 | Pharmacological similarity methods |

| F-Score (Traditional CV) | 0.86 | Pharmacological similarity methods | ||

| Recommender Systems (Pinterest) [12] | PinSage (GNN) | Hit-Rate | 150% improvement | Previous production model |

| Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR) | 60% improvement | Previous production model |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Knowledge Graph Embedding for Drug Repositioning

This protocol outlines the steps for using knowledge graph embedding to generate drug repositioning hypotheses, as applied in recent research [14] [11].

- Knowledge Graph Construction: Integrate multi-source biomedical data (e.g., drugs, diseases, genes, proteins) into a heterogeneous knowledge graph. Each fact is represented as a triple (head, relation, tail).

- Model Selection and Training: Select a knowledge graph embedding model (e.g., TransE, DistMult, ComplEx). Innovative approaches may integrate an attention mechanism to weigh the importance of different attributes or relations [14]. The model is trained to learn vector embeddings for all entities and relations by maximizing the plausibility of true triples in the graph.

- Link Prediction for Hypothesis Generation: Formulate drug repositioning as a link prediction task. Specifically, search for high-scoring, plausible triples of the form

(Drug, "Treatment", Disease)that are not yet present in the original knowledge graph. - Validation: Rank all potential new

(Drug, "Treatment", Disease)triples. Validate the top-ranked candidates by comparing them against independent sources, such as ongoing clinical trials or new literature, not used during model training [14] [11].

Protocol 2: Realistic Evaluation for Drug-Drug Interaction Prediction

This protocol describes a rigorous evaluation strategy to avoid inflated performance metrics when predicting drug-drug interactions (DDIs) [15].

- Data Preparation: Construct a knowledge graph from a reliable DDI source like DrugBank.

- Generate Embeddings: Use a graph embedding method (e.g., RDF2Vec) to learn vector representations for each drug.

- Implement Disjoint Cross-Validation:

- Drug-wise Disjoint CV: Split the dataset into k-folds such that all DDIs for a given drug appear exclusively in one fold. This tests the model's ability to predict interactions for drugs with no known DDIs.

- Pairwise Disjoint CV: Split the dataset into k-folds such that all DDIs for a given pair of drugs appear exclusively in one fold. This tests the model's ability to predict interactions between two drugs that both have no known DDIs.

- Train and Evaluate: For each fold, train a classifier (e.g., Logistic Regression, Random Forest) on the training drug vectors to predict DDIs. Evaluate the model's performance on the held-out test sets from both CV scenarios. Expect lower but more realistic performance scores in the pairwise disjoint setting [15].

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

Graph Embedding Concept: From Graph to Vector Space

The TransE Model Mechanism

LLM4MS Workflow for Mass Spectrometry

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Graph Embedding |

|---|---|---|

| PyKEEN [13] | Python Library | A comprehensive toolkit for training and evaluating Knowledge Graph Embedding models (e.g., TransE, DistMult, ComplEx). |

| AmpliGraph [13] | Python Library | A TensorFlow-based library for link prediction on knowledge graphs, supporting various models and offering easy training. |

| GraphSAGE [10] [12] | Algorithm / Framework | An inductive graph embedding method that generates node representations by sampling and aggregating features from a node's local neighborhood. |

| GNBR (Global Network of Biomedical Relationships) [11] | Knowledge Graph | A large, heterogeneous knowledge graph linking drugs, diseases, and genes, derived from PubMed abstracts via NLP. |

| RDF2Vec [15] | Embedding Method | Generates embeddings for entities in RDF graphs using random walks and language modeling, effective for DDI prediction. |

| LLM4MS [4] | Specialized Method | A method that uses fine-tuned Large Language Models to generate chemically-informed embeddings for mass spectra. |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: The FIORA model fails to predict any fragment ions for my compound. What could be wrong? A: This often occurs due to an input format issue. Ensure your molecular structure is provided as a valid, machine-readable graph representation (like an SDF or MOL file) and that all atoms and bonds are correctly defined. The model requires a complete graph structure to simulate bond dissociation events [16].

Q: How can I improve the prediction accuracy for novel metabolites not in the training set? A: FIORA's performance relies on the local molecular neighborhood of bonds. For novel structures, ensure the training data includes compounds with analogous functional groups or subgraph structures. The model's generalizability is higher when local breaking patterns are shared with compounds in the training library, even if the overall molecular structure is dissimilar [16].

Q: My predicted spectrum has correct fragments but incorrect intensities. Which parameters most affect this? A: Fragment ion abundances are highly sensitive to the instrument's collision energy. FIORA can be conditioned on this parameter; verify that the collision energy value used during model prediction matches that of your experimental setup. Also, confirm you are using the correct ionization mode ([M+H]+ or [M-H]-) as intensity patterns differ significantly between them [16].

Q: What is the first step when my experimental spectrum shows a major peak that is completely missing from FIORA's prediction?

A: This suggests a potential single-step fragmentation limitation. First, use the provided annotate_fragments tool to check if the peak corresponds to a neutral loss fragment or a multi-step fragmentation event not currently modeled by FIORA. Manually inspecting the fragmentation pathways of structurally similar compounds in databases like PubChem or HMDB can provide clues [16].

Common Errors & Solutions

| Error Message / Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

No valid fragments generated |

Invalid molecular graph input or unsupported atom types [16]. | Validate input file structure and sanitize the molecule (e.g., using RDKit). |

GPU Memory Error |

Molecular graph or batch size is too large for available GPU memory [16]. | Reduce the batch_size parameter or use a GPU with higher RAM. |

Low intensity correlation |

Mismatch between predicted and experimental collision energy or ionization mode [16]. | Re-run prediction with correct collision_energy and ion_mode parameters. |

Peak m/z shift |

Incorrect adduct specification or protonation state [16]. | Verify the precursor ion type ([M+H]+ or [M-H]-) is set correctly. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Benchmarking FIORA Performance

Objective: To evaluate FIORA's prediction quality against state-of-the-art algorithms (ICEBERG and CFM-ID) using a curated test set of mass spectra [16].

Data Curation:

- Source a publicly available dataset (e.g., from GNPS) containing tandem mass spectra for known compounds.

- Split the data into training and test sets, ensuring no structural overlap between the sets to test generalizability.

- For the test set, obtain the canonical SMILES or InChI representations for each compound.

Spectral Prediction:

- Process the test set compounds through FIORA, ICEBERG, and CFM-ID using their respective publicly available implementations.

- For each model, use the recommended settings and specify the correct collision energy and ionization mode.

Data Analysis:

- For each predicted spectrum, calculate the spectral similarity score (e.g., cosine similarity) against the experimental reference spectrum.

- Record the run-time for each prediction to compare computational efficiency.

- Compile the results into a summary table for comparative analysis.

FIORA Performance Benchmarking Results

The following table summarizes quantitative performance data for FIORA against other top-tier methods, demonstrating its superior accuracy and efficiency [16].

| Algorithm | Average Cosine Similarity | Prediction Speed (sec/compound) | Supports CCS & RT Prediction | Ionization Modes Supported |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIORA | Exceeds ICEBERG & CFM-ID | Fast (GPU accelerated) | Yes | Both Positive & Negative [16] |

| ICEBERG | Lower than FIORA | Slow | No | Positive only [16] |

| CFM-ID | Lower than FIORA | Very Slow | No | Both Positive & Negative [16] |

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| PubChem / HMDB | Large knowledge bases providing known chemical structures and properties, essential for sourcing molecular graphs for prediction [16]. |

| GNPS / METLIN | Public spectral databases used for obtaining experimental reference spectra to benchmark and validate in-silico predictions [16]. |

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit used for manipulating molecular structures, validating file formats, and generating graph representations [16]. |

| SIRIUS Suite | Software tools used for compound identification and as a complementary method to validate FIORA's putative annotations [16]. |

Workflow & Conceptual Diagrams

DOT Visualization Code

MS Analysis Ecosystem

Bond Dissociation Logic

Node Embeddings, Edge Embeddings, and Structural Similarity

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Node Embedding Generation

Problem: Poor clustering of metabolite nodes in the embedded space.

- Potential Cause 1: Incorrect similarity metric for random walks. The choice of similarity metric (e.g., cosine, modified cosine) for generating walks on the mass spectrometry correlation graph fundamentally affects what structural information the embeddings capture [17].

- Solution: Experiment with different spectral similarity measures as the basis for the random walks. Validate the chosen metric on a small subset of data with known structural relationships.

- Potential Cause 2: Inadequate hyperparameter tuning for the embedding model. Parameters like walk length, number of walks per node, and embedding dimensions are critical [8].

- Solution: Systematically vary key parameters using a grid search. Performance should be evaluated based on downstream tasks like node classification accuracy or the biological plausibility of the resulting clusters [18].

Problem: Generated node embeddings are not robust across different instrument types.

- Potential Cause: The model has learned instrument-specific artifacts rather than underlying chemical properties. This is a common batch effect [17].

- Solution: Incorporate data augmentation during training that simulates variations in instrument resolution and collision energy. Alternatively, use a benchmark dataset with a structured train/test split that controls for instrumental differences to assess generalization [17].

Troubleshooting Edge Embedding and Link Prediction

Problem: Low accuracy in predicting novel protein-protein or drug-target interactions.

- Potential Cause 1: High-dimensional and sparse feature space, leading to poor model generalization [19].

- Solution: Implement a dedicated dimensionality reduction layer, such as an encoder-decoder module, to transform features into a more discriminative and lower-dimensional space before generating edge embeddings [19].

- Potential Cause 2: Lack of negative samples (non-interacting pairs) during training, which can reduce prediction accuracy [20].

- Solution: Integrate negative data sampling from curated databases of non-interacting proteins or use techniques like random sampling from unlikely pairs [20].

Problem: Inability to predict relationships between disparate node types (e.g., drug and disease) in a heterogeneous graph.

- Potential Cause: The model architecture does not adequately account for different node and edge types in heterogeneous knowledge graphs [8] [20].

- Solution: Use embedding algorithms designed for heterogeneous graphs, such as translational embedding models (e.g., TransE, TransH) or other multi-relation learning approaches that can handle multiple entity types [20].

Troubleshooting Structural Similarity Measurement

Problem: Structural similarity scores do not align with known chemical relationships.

- Potential Cause: The machine learning model used for similarity prediction has overfitted to the training data and fails to generalize to structurally novel compounds [17].

- Solution: Employ a benchmark framework that uses a train/test split with controlled structural similarity between the sets. This ensures the model is evaluated on its ability to generalize to new structural scaffolds [17].

Problem: Slow retrieval speed when matching a query spectrum against a large library.

- Potential Cause: The similarity search is performed using an inefficient metric or a non-optimized library.

- Solution: Utilize embedding-based methods like LLM4MS or Spec2Vec, which generate compact vector representations of spectra. These enable ultra-fast cosine similarity searches, with methods like LLM4MS capable of nearly 15,000 queries per second against a million-scale library [4].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the practical advantages of using graph embeddings over traditional statistical methods for MS data filtration? Traditional statistical methods (e.g., ANOVA, t-test) can overfilter raw MS data, potentially removing biologically relevant signals. Graph embedding techniques, like those in GEMNA, analyze the data as a network, allowing for the identification of "real" signals based on their contextual relationships within the metabolic network. This approach can reveal more metabolomic changes than traditional filtering [18].

Q2: How do node embeddings and edge embeddings differ in the context of biomedical networks?

- Node Embeddings represent the position and role of a single entity (e.g., a metabolite, protein, or drug) within the broader network. They are used for tasks like classifying cell types or predicting novel drug functions [8] [18].

- Edge Embeddings represent the relationship or potential interaction between two nodes. They are powerful for predicting unknown links, such as new protein-protein interactions or drug-target bindings, which is crucial for drug repurposing [20].

Q3: My graph embedding model for drug repurposing performs well in training but poorly in validation. What could be wrong? This is often a sign of data leakage or a lack of negative sampling. Ensure your training and validation sets are strictly separated, with no overlapping structures or relationships. Furthermore, confirm that your training data includes confirmed negative examples (non-interactions) to prevent the model from learning unrealistic patterns [20] [17].

Q4: What is the state-of-the-art for measuring structural similarity from MS/MS spectra? While algorithmic approaches like cosine similarity are common, machine learning models now set the state-of-the-art. These include:

- MS2DeepScore: A neural network that learns a spectral similarity score from data [17].

- Spec2Vec: An unsupervised method using word2vec-inspired embeddings to capture intrinsic structural similarities [4] [21].

- LLM4MS: Leverages fine-tuned Large Language Models to generate spectral embeddings that incorporate chemical expert knowledge, achieving a top-1 accuracy of 66.3% on a large-scale benchmark [4].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Benchmarking MS/MS Structural Similarity Models

This protocol outlines how to evaluate machine learning models that predict structural similarity from MS/MS spectra [17].

- Dataset Curation: Collect and harmonize public data from GNPS and MassBank. Canonicalize molecular structures and remove duplicate spectra.

- Quality Filtering: Filter spectra to keep only those with a precursor m/z matching their annotation and significant fragmentation signals.

- Create Train/Test Splits: Use a method that ensures diversity in both pairwise structural similarity and train-test similarity. This involves:

- Binning: Group test structures into bins based on their maximum Tanimoto similarity to any training set structure.

- Random Walk Sampling: Sample pairs of spectra to ensure good coverage of both similar and dissimilar pairs across all bins.

- Model Evaluation: Evaluate models on the test set using domain-inspired metrics such as Recall@K for retrieval tasks.

Protocol 2: Creating a Graph Embedding-Based Metabolomics Network (GEMNA)

This protocol describes the GEMNA workflow for analyzing MS-based metabolomics data [18].

- Input Data: Provide data from flow injection-MS or chromatography-coupled-MS systems.

- Network Construction: Build a graph where nodes represent MS signals (potential metabolites) and edges represent strong correlations or co-occurrences.

- Embedding Filtration: Use a Graph Neural Network (GNN) to generate node embeddings. This step helps distinguish "real" biological signals from noise.

- Anomaly Detection: Apply an anomaly detection algorithm on the embeddings to identify and filter out outliers or artifacts.

- Output: Generate a filtered MS signal list and a dashboard visualizing metabolic changes between sample groups.

Quantitative Performance of Spectral Similarity Methods

The following table summarizes the performance of different methods on a large-scale compound identification task (NIST23 test set against a million-scale library) [4].

| Method | Approach | Recall@1 | Recall@10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| LLM4MS | LLM-based Spectral Embedding | 66.3% | 92.7% |

| Spec2Vec | Word2Vec-inspired Embedding | ~52.6%* | - |

| WCS | Weighted Cosine Similarity | Lower than ML | Lower than ML |

*Calculated based on the reported 13.7% improvement of LLM4MS over Spec2Vec.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Neo4j | A graph database platform used to manage biological knowledge graphs for drug repurposing and R&D knowledge management [22]. |

| GNPS/MassBank | Public repositories of mass spectrometry data used as primary sources for training and benchmarking machine learning models [17]. |

| PyTorch Geometric | A library for deep learning on graphs, used to build GNNs for node embedding and graph analysis tasks [18]. |

| DreaMS Atlas | A pre-trained transformer model and molecular network of 201 million MS/MS spectra for assisting in spectral annotation and networking [21]. |

| MADGEN | A tool for de novo molecular structure generation guided by MS/MS spectra, used to explore dark chemical space [23]. |

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Core Workflow for Graph Embedding in Mass Spectrometry

Graph Embedding-Based MS Analysis

Diagram 2: Machine Learning for Structural Similarity

Spectral Similarity Learning

The Critical Limitation of Traditional Statistical Filtration (ANOVA, t-Test)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary statistical limitation of methods like ANOVA in analyzing mass spectrometry data? The primary limitation is that methods like ANOVA are univariate. They analyze one variable (e.g., one ion peak) at a time across your sample groups. When applied to mass spectrometry data, which contains thousands of features, this leads to the multiple comparisons problem: the more statistical tests you perform, the higher the chance of false positives. Furthermore, ANOVA cannot identify which specific group means are different if it finds a significant result; it only indicates that not all groups are the same [24] [25].

Q2: How does graph embedding address the shortcomings of traditional statistical filtration? Graph embedding is a multivariate technique that overcomes key shortcomings. It transforms the entire complex, high-dimensional mass spectrometry dataset into a lower-dimensional space while preserving the underlying structural relationships between data points (nodes) [8]. Unlike ANOVA, it can capture non-linear interactions and patterns within the data. This provides a more holistic view, helping to distinguish true biological signals from noise and revealing subtle patterns that univariate methods miss [8] [19].

Q3: My mass spectrometry data has a strong batch effect. Can graph embedding help with this? Yes, a key advantage of advanced models that use embedding-like concepts is their ability to integrate strategies to minimize batch effects. Batch effects are systematic biases from non-biological sources (e.g., sample processing on different days) that can obscure true biological variation. Modern deep learning frameworks designed for MS data classification can incorporate modules, such as batch normalization layers, directly into an end-to-end training process. This helps to reduce inter-batch differences and improve the model's ability to learn robust, generalizable features [19].

Q4: What are the common tasks where graph embedding is applied to biomedical data? Graph embedding techniques are particularly powerful for several core bioinformatics tasks [8]:

- Node Classification: Predicting the type or function of a biological molecule (e.g., classifying a protein's role).

- Link Prediction: Inferring new or missing interactions between entities (e.g., predicting novel protein-protein or drug-protein interactions).

- Community Detection: Identifying clusters or functional modules within a biological network (e.g., finding groups of metabolites that work together in a pathway).

Q5: Why are techniques like LLM4MS and MS-DREDFeaMiC considered superior to traditional similarity metrics for compound identification? These methods are superior because they move beyond simple spectral comparison. They leverage deep learning to generate chemically informed embeddings.

- LLM4MS uses a large language model imbued with latent chemical knowledge to prioritize diagnostically important peaks (like base peaks and high-mass ions), leading to more accurate matching than metrics like Weighted Cosine Similarity or Spec2Vec [4].

- MS-DREDFeaMiC is an end-to-end deep learning model that integrates dimensionality reduction, feature extraction, and classification. It is specifically designed to handle the high-dimensionality and batch effects prevalent in MS data, achieving higher classification accuracy than other models like Transformer or Mamba [19].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: High False Discovery Rate After ANOVA Filtration

Problem: After applying ANOVA (or t-tests) with multiple comparison correction to filter significant features, the resulting candidate list still contains many false leads when validated.

| Potential Cause | Solution | Key Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Comparisons Problem: Correcting for thousands of tests drastically reduces statistical power, but some remaining significant features may still be spurious. | Use graph embedding as a pre-filter to reduce dimensionality based on network structure before applying statistical tests. | Shift from a purely statistical to a network-based worldview. Focus on features that are both statistically significant and centrally located or well-connected within the data's inherent structure [8]. |

| Ignoring Data Structure: Univariate tests cannot see the correlation or co-variance structure between ion peaks, mistaking correlated noise for a true signal. | Apply graph embedding to learn a lower-dimensional representation of your entire dataset. This new feature space will better capture the true, underlying biological variation [19]. | Leverage multivariate analysis to account for the complex, non-linear relationships in MS data that ANOVA is not designed to handle [19]. |

Issue 2: Failure to Identify Subtle but Biologically Important Patterns

Problem: Your analysis fails to distinguish between sample classes (e.g., diseased vs. healthy) when the differences are driven by coordinated, small changes across many features rather than large changes in a few.

Experimental Protocol: Using Graph Embedding for Pattern Discovery

- Network Construction: Convert your processed mass spectrometry data (peak lists) into a graph. Represent each sample or each molecular feature (e.g., a metabolite) as a node [8].

- Edge Definition: Establish edges (connections) between nodes based on a measure of similarity. For features, this could be the correlation of their intensity profiles across samples. For samples, it could be their overall spectral similarity [8].

- Embedding Generation: Apply a graph embedding algorithm (e.g., a random walk-based or matrix factorization-based method) to the network. This will transform each node into a fixed-length vector in a lower-dimensional space [8].

- Downstream Analysis: Use the resulting node embeddings for clustering, classification, or visualization. Patterns and clusters that were invisible in the original high-dimensional space often become apparent in the embedding space, revealing the subtle distinctions between sample classes [19].

Diagram: Graph Embedding Workflow for MS Data.

Issue 3: Model Performance Degrades with New Data Batches

Problem: A classifier trained on one set of mass spectrometry data performs poorly when applied to new data collected at a later time or on a different instrument, due to batch effects.

Methodology: End-to-End Learning with Batch Effect Integration

Modern deep learning architectures like MS-DREDFeaMiC are designed to combat this. The workflow integrates batch effect correction directly into the model training [19]:

- Input: High-dimensional mass spectral data.

- Dimensionality Reduction (DimRed) Layer: The data is passed through a layer that includes a Batch Normalization (BN) step. This layer accelerates convergence and reduces the influence of batch-to-batch variations by normalizing the inputs.

- Encoder-Decoder Module: This module transforms the feature space to enhance the discriminability between different sample categories (e.g., diseased vs. healthy).

- Feature-Mixer: This module uses a State Space Model (SSM) to learn complementary feature representations, further strengthening the model's robustness.

- Output: The model produces a classification (e.g., disease diagnosis) based on features that are more stable and less susceptible to batch noise.

Diagram: Integrated Batch Effect Reduction in a Deep Learning Model.

Performance Comparison Table

The table below quantifies the performance gap between traditional methods and modern, embedding-based approaches.

| Method | Core Principle | Key Limitation | Performance Metric & Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANOVA / t-Test | Univariate hypothesis testing for difference in means between groups [24] [25]. | "Multiple comparisons" problem; cannot identify specific differing pairs; ignores multivariate structure [24] [25]. | N/A (Fundamentally unsuitable for direct, high-dimensional MS data comparison) |

| Weighted Cosine Similarity (WCS) | Traditional spectral matching based on direct intensity comparison [4]. | Struggles with subtle structural variations; can assign high scores to spectra of distinct compounds [4]. | Recall@1: Lower than modern methods (Baseline for LLM4MS comparison) [4]. |

| Spec2Vec | Machine learning; uses word2vec-inspired embeddings to capture spectral similarity [4]. | Relies on spectral context alone, lacks inherent chemical knowledge; can be misled by intensity distribution [4]. | Recall@1: ~52.6% (Baseline, improved upon by LLM4MS) [4]. |

| LLM4MS | Generates spectral embeddings using a fine-tuned Large Language Model with latent chemical knowledge [4]. | Computationally demanding for training; requires fine-tuning for optimal performance. | Recall@1: 66.3% (13.7% absolute improvement over Spec2Vec) [4]. |

| MS-DREDFeaMiC | End-to-end deep learning with integrated dimensionality reduction and batch normalization [19]. | Model complexity requires significant computational resources and data for training. | Average Accuracy: 6.6% and 6.3% higher than Transformer and Mamba models, respectively [19]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Million-Scale In-Silico EI-MS Library | A large, computationally predicted spectral library used as a reference database for benchmarking compound identification methods like LLM4MS against traditional libraries [4]. |

| NIST23 Mass Spectral Library | A high-quality, curated experimental library. Used as a source of test/query spectra to evaluate the accuracy of spectral matching algorithms [4]. |

| Pooled Quality Control (QC) Samples | A mixture of all study samples. Used to monitor instrument stability and is critical for data normalization methods (e.g., LOESS, SERRF) to correct for systematic technical variation across a batch run [26]. |

| Batch Normalization (BN) Layer | A standard component in deep learning models (e.g., MS-DREDFeaMiC) that normalizes the inputs to a layer for each mini-batch. This accelerates training and helps mitigate the impact of internal covariate shift, which includes batch effects [19]. |

| State Space Model (SSM) | A type of sequence model used in the feature-mixer module of MS-DREDFeaMiC. It helps in learning complex, long-range dependencies within the feature data, contributing to robust feature representation [19]. |

From Theory to Pipeline: Implementing Graph Embedding Models for MS Signal Filtration

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between transductive and inductive learning in graph embeddings, and why does it matter for my research?

Transductive models like DeepWalk and Node2Vec learn embeddings for a single, fixed graph. They cannot generate embeddings for nodes not seen during training. In contrast, inductive models like GraphSAGE learn a function that generates embeddings by sampling and aggregating features from a node's local neighborhood. This allows it to create embeddings for previously unseen nodes or entirely new graphs, which is crucial for dynamic datasets or when your mass spectrometry data evolves with new experiments [27] [28].

2. During my Node2Vec experiments, the results are not reproducible even with a fixed random seed. Is this a bug?

No, this is a known characteristic of the Node2Vec algorithm in some implementations. The embeddings can be non-deterministic between runs due to randomness in the initial node embedding vectors and the random walk sampling process. It is recommended not to use Node2Vec as a step within a machine learning pipeline where deterministic features are required for production models, but it is acceptable for experimental analysis [29].

3. How do I choose between DeepWalk and Node2Vec for analyzing molecular structures in mass spectrometry data?

DeepWalk uses unbiased random walks, where the next step in a walk is chosen uniformly at random from a node's neighbors. Node2Vec employs a biased random walk, controlled by the returnFactor (p) and inOutFactor (q) parameters, which allows it to explore neighborhoods that are more homophilic (close to the start node) or more structural (fanning out further). If the local topology and specific connectivity patterns of your molecular graph are critical, Node2Vec's flexibility may yield better results [30] [31] [29].

4. My graph dataset is very large. Which algorithm is most scalable?

DeepWalk and Node2Vec are generally scalable as they process the graph via random walks, which do not require the entire graph to be loaded into memory at once. However, GraphSAGE is specifically designed for large graphs and offers superior scalability for inductive tasks, as it learns an aggregator function instead of individual embeddings for every node [31] [27] [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Performance in Downstream Node Classification

Problem: After generating node embeddings, your classifier fails to distinguish between different node classes (e.g., different molecular signatures).

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Incorrect hyperparameter tuning for random walks.

- Solution: For Node2Vec, adjust

returnFactor(p) andinOutFactor(q). A higherreturnFactorkeeps the walk close to the start node, while a higherinOutFactorencourages the walk to explore nodes further away. For mass spectrometry data where local functional groups are key, a lowerinOutFactormight be beneficial [30] [29].

- Solution: For Node2Vec, adjust

- Cause: The embedding dimension is too low to capture complex features.

- Solution: Increase the

embeddingDimension(e.g., from 128 to 256) to allow the model to capture more nuanced information from the graph structure [29].

- Solution: Increase the

- Cause: The random walks are too short to capture meaningful context.

Issue 2: Algorithm Does Not Generalize to New Data

Problem: Your trained model performs well on the original graph but fails on a new, similar graph or new nodes added to the existing graph.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Using a transductive algorithm (DeepWalk, Node2Vec) on a dynamic graph.

- Cause: Feature information for new nodes is not being utilized.

- Solution: Ensure that you are using a model that incorporates node features. While DeepWalk and Node2Vec can operate on graph structure alone, GraphSAGE explicitly aggregates node features from neighbors, which is often critical for generalization [28].

Issue 3: Long Training Times on Large Graphs

Problem: The model takes an impractically long time to train.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inefficient sampling of the neighborhood.

- Solution: For GraphSAGE, instead of using all neighbors, use a fixed-size sample for each node (e.g., sample 10 neighbors per node). This dramatically reduces computational complexity [28].

- Cause: Too many random walks per node.

- Cause: A large negative sampling rate.

Algorithm Comparison & Technical Specifications

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Graph Embedding Algorithms

| Feature | DeepWalk | Node2Vec | GraphSAGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Learning Type | Transductive | Transductive | Inductive |

| Base Mechanism | Uniform Random Walks | Biased Random Walks | Neighborhood Aggregation |

| Key Hyperparameters | Walk Length, Walks per Node, Window Size | Walk Length, Walks per Node, Return Factor (p), In-Out Factor (q) | Depth (K), Aggregator Type, Sample Size |

| Utilizes Node Features | No | No | Yes |

| Ideal for Evolving Graphs | No | No | Yes |

Table 2: Common Hyperparameters and Recommended Values

| Hyperparameter | Description | DeepWalk/Node2Vec Typical Range | GraphSAGE Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Embedding Dimension | Size of the output vector per node. | 128 - 256 [29] | 256 - 512 [28] |

| Walk Length | Number of steps in a single random walk. | 80 - 100 [31] [29] | Not Applicable |

| Walks Per Node | Number of walks started from each node. | 10 - 20 [29] | Not Applicable |

| Context Window Size | The maximum distance between a node and its context. | 5 - 10 [30] | Not Applicable |

| Return Factor (p) | Likelihood of immediately revisiting a node. | 0.5 - 2.0 [30] [29] | Not Applicable |

| In-Out Factor (q) | Ratio of BFS vs. DFS-style exploration. | 0.5 - 2.0 [30] [29] | Not Applicable |

| Neighborhood Depth (K) | Number of neighbor layers to aggregate. | Not Applicable | 1 - 3 [28] |

| Aggregator Type | Function to combine neighbor info (e.g., Mean, LSTM, Pooling). | Not Applicable | Mean Aggregator is a common starting point [28] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generating Embeddings with Node2Vec

- Input Preparation: Represent your mass spectrometry data as a graph. For example, nodes can represent molecules or peaks, and edges can represent spectral similarity or co-occurrence.

- Parameter Configuration: Set hyperparameters based on Table 2. For initial experiments, use:

walkLength=80,walksPerNode=10,embeddingDimension=128,windowSize=10,returnFactor=1.0,inOutFactor=1.0[29]. - Generate Random Walks: Execute second-order biased random walks across the graph for each node, as defined in the

node2vecWalkfunction [32]. - Train Skip-Gram Model: Use the generated walks as "sentences" to train a Skip-gram model with Negative Sampling (SGNS). The model learns to predict the context nodes for a given target node [30].

- Extract Embeddings: The weights of the hidden layer of the trained neural network are the final node embeddings, which can be used for downstream tasks like clustering or classification [30].

Protocol 2: Inductive Learning with GraphSAGE

- Input Preparation: Define your graph and ensure each node has an input feature vector (e.g., molecular descriptors).

- Specify Aggregator and Parameters: Choose an aggregator function (Mean is a robust default). Set the number of layers (K), which defines the number of hops the model looks away from a node, and the sample size per layer (e.g., sample 10 neighbors at K=1) [28].

- Forward Pass (for each node):

- Initialize: Set the initial representation of each node to its input features.

- Iterate (for k = 1 to K):

- Aggregate the representations from the node's sampled neighbors from the previous layer (k-1).

- Concatenate the node's current representation with the aggregated neighbor vector.

- Pass this combined vector through a learned weight matrix and a non-linear activation function (e.g., ReLU) to form the node's representation at layer k [28].

- Output: The final representation at layer K is the embedding for the node. This process allows embeddings to be generated for any node, as long as its features and connections are known [27] [28].

Algorithm Workflow Diagrams

Node2Vec Biased Random Walk

DeepWalk & Skip-gram Training

GraphSAGE Neighborhood Aggregation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for Graph Embedding Research

| Tool / Library | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| NetworkX | Graph creation and manipulation. | Ideal for prototyping graph structures from your mass spectrometry data and running basic algorithms [31]. |

| KarateClub | A unified API for unsupervised graph embedding algorithms. | Provides off-the-shelf implementations of DeepWalk, Node2Vec, and many others, perfect for rapid benchmarking [31]. |

| Stellargraph | Libraries for graph machine learning. | Offers scalable, production-ready implementations of algorithms like GraphSAGE for more extensive experiments [27]. |

| PyTorch / TensorFlow | Deep learning frameworks. | Essential for customizing and implementing Graph Neural Networks and training models on GPU hardware [28]. |

| Graph Data Science Library (Neo4j) | Graph analytics and ML within a database. | Useful for running Node2Vec and other algorithms directly on large graphs stored in a Neo4j database [29]. |

Graph Embedding-based Metabolomics Network Analysis (GEMNA) represents a novel deep learning approach that leverages node embeddings (powered by Graph Neural Networks), edge embeddings, and anomaly detection algorithms to analyze data generated by mass spectrometry (MS)-based metabolomics [18] [5]. This methodology addresses significant challenges in traditional MS data processing, where statistical approaches tend to overfilter raw data, potentially removing relevant information and leading to the identification of fewer metabolomic changes [18].

In the context of mass spectrometry data filtration research, GEMNA offers a transformative approach by applying graph representation learning to biomedical data, particularly metabolite-metabolite networks [18]. Unlike traditional methods that rely heavily on statistical filtering (ANOVA, t-Test, coefficient of variation), GEMNA uses advanced computational techniques to preserve relevant biological signals while effectively reducing noise, enabling researchers to better understand fold changes in metabolic networks [5].

Technical Support Center

System Requirements & Installation Guide

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What are the minimum and recommended system requirements for running GEMNA? A: GEMNA can operate on computers with 16 GB of RAM and 8 GB of VRAM, though for optimal performance with large datasets, we recommend a system with 32 cores, 256 GB of RAM, and 2x NVIDIA RTX A6000 with 48 GB of VRAM [18]. The backend is implemented using Django REST framework with PyTorch Geometric and PyOD libraries, while the frontend uses Vue.js with the Nuxt framework [18].

Q: Where can I find the source code for GEMNA? A: The source code is publicly available and divided into two repositories. The backend code is at: https://github.com/win7/GEMNABackend.git, and the frontend code is at: https://github.com/win7/GEMNAFrontend.git [18].

Q: How long does a typical analysis take with GEMNA? A: Processing time varies by dataset size and system configuration. For example, the Mentos candy dataset took approximately 8.45 minutes on a high-performance AMD Ryzen system and 12.66 minutes on a system with recommended specifications [18].

Troubleshooting Guide

Q: I'm experiencing memory issues when processing large datasets. What can I do?

- Issue: Insufficient RAM or VRAM for large metabolomic datasets.

- Solution: Reduce batch size in the configuration settings, ensure no other memory-intensive applications are running, or upgrade to the recommended system specifications [18].

Q: The model fails to start or import required libraries.

- Issue: Missing dependencies or version conflicts.

- Solution: Create a fresh Python virtual environment and install all requirements using the provided requirements.txt file from the GitHub repository [18].

Q: I'm getting poor clustering results with my data.

- Issue: Suboptimal hyperparameters or data preprocessing.

- Solution: Verify your data normalization approach, adjust the embedding dimensions, or consult the example datasets provided in the repository to ensure proper data formatting [5].

Data Processing & Analysis Support

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What input data formats does GEMNA support? A: GEMNA can accept MS data obtained from either (i) flow injection MS or chromatography coupled-MS systems [18]. The tool identifies "real" signals using embedding filtration coupled with a GNN model and outputs filtered MS-based signal lists with visualization dashboards [18].

Q: How does GEMNA compare to traditional statistical approaches? A: In comparative studies, GEMNA demonstrated significantly better performance than traditional tools. For example, in an untargeted volatile study on Mentos candy, GEMNA achieved a silhouette score of 0.409 compared to -0.004 for the traditional approach [5].

Q: Can GEMNA handle both identified and unidentified metabolites? A: Yes, one of GEMNA's strengths is its ability to work with both identified metabolites and unknown features, which is particularly valuable for exploring the "dark matter" of metabolomics where many signals remain unidentified [33].

Troubleshooting Guide

Q: My correlation networks show unexpected patterns or artifacts.

- Issue: Potential batch effects or technical artifacts in the MS data.

- Solution: Implement batch correction techniques and ensure proper quality control measures during data acquisition. Use GEMNA's anomaly detection capabilities to identify potential outliers [18].

Q: The graph embeddings aren't capturing meaningful biological relationships.

- Issue: Suboptimal parameter tuning or insufficient data preprocessing.

- Solution: Adjust the embedding dimensions, modify the random walk parameters for graph construction, or ensure proper peak alignment and normalization before analysis [8].

Q: I'm having difficulty interpreting the network visualization outputs.

- Issue: Complex network structures with too many nodes and edges.

- Solution: Use GEMNA's filtering options to focus on highly correlated pairs, adjust the correlation threshold, or utilize the subnetwork extraction features to focus on specific metabolic pathways of interest [33].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

GEMNA Workflow and Implementation

The following diagram illustrates the complete GEMNA experimental workflow, from raw data input to biological interpretation:

GEMNA Experimental Workflow

Computational Architecture of GEMNA

The diagram below details GEMNA's computational architecture, showing how graph neural networks process mass spectrometry data:

GEMNA Computational Architecture

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Metabolic Network Construction from MS Data

- Input Raw MS Data: Begin with raw mass spectrometry data in either flow injection MS or chromatography-coupled MS format [18]

- Peak Detection and Alignment: Identify metabolic features across samples using established peak detection algorithms

- Correlation Matrix Calculation: Compute pairwise correlations between all detected metabolic features to establish potential biological relationships [33]

- Graph Formation: Construct a metabolic network where nodes represent metabolites and edges represent significant correlations [8]

Protocol 2: Graph Embedding with GEMNA

- Network Input: Feed the constructed metabolic network into GEMNA's graph neural network architecture [18]

- Node Embedding Generation: Apply GNN-powered embedding to transform each node (metabolite) into a lower-dimensional vector representation while preserving network topology [18]

- Edge Embedding Computation: Generate embeddings for relationships between metabolites to capture interaction patterns [18]

- Anomaly Detection: Apply anomaly detection algorithms to distinguish real biological signals from noise and artifacts [18]

- Network Filtering: Remove spurious connections while preserving biologically relevant interactions [5]

Protocol 3: Validation and Biological Interpretation

- Cluster Quality Assessment: Evaluate the quality of resulting metabolic clusters using metrics such as silhouette scores [5]

- Comparative Analysis: Compare GEMNA's performance against traditional statistical approaches (ANOVA, t-test) for identifying metabolomic changes [5]

- Pathway Mapping: Map significant metabolic clusters to known biochemical pathways using enrichment analysis [33]

- Biological Validation: Design follow-up experiments to test hypotheses generated from network analysis

Performance Metrics & Comparative Analysis

Quantitative Performance Assessment

Table 1: GEMNA Performance Across Experimental Datasets

| Dataset | Metabolites | Phenotypes | Biological Rep. | Analytical Rep. | GEMNA Performance | Traditional Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutant | Multiple | WT, PFK1, ZWF1 | 5, 2, 3 | 40, 39, 40 | Improved cluster separation | Overfiltering issues [18] |

| Leaf | Multiple | Control, Treatment | 3, 3 | 3, 3 | Enhanced stress response detection | Reduced sensitivity [18] |

| Mentos | Volatiles | Orange, Red, Yellow | 2, 2, 2 | 3, 3, 3 | Silhouette score: 0.409 | Silhouette score: -0.004 [5] |

Table 2: System Requirements and Performance Benchmarks

| Component | Minimum Specification | Recommended Specification | Example Processing Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| RAM | 16 GB | 256 GB | Mentos dataset: 12.66 min (min) vs 8.45 min (rec) [18] |

| GPU VRAM | 8 GB | 48 GB (2x A6000) | Dependent on dataset size [18] |

| Processor | Multi-core CPU | 32-core AMD Ryzen Threadripper | Optimized for parallel processing [18] |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for GEMNA Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Platform | Function/Purpose | Implementation in GEMNA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Programming Frameworks | PyTorch Geometric | Graph neural network operations | Backend GNN implementation [18] |

| Django REST Framework | API and backend services | Web service architecture [18] | |

| Vue.js with Nuxt | Frontend user interface | Interactive visualization dashboard [18] | |

| Analytical Libraries | PyOD | Anomaly detection algorithms | Identification of real MS signals [18] |

| UMAP | Dimensionality reduction | Visualization of embedded spaces [8] | |

| Mass Spectrometry Platforms | ESI-MS Systems | Metabolite detection and quantification | Raw data generation for mutant and leaf datasets [18] |

| Orbitrap Q-Exactive HF | High-resolution mass spectrometry | Leaf dataset acquisition [18] | |

| Computational Resources | NVIDIA RTX A6000 | High-performance GPU computing | Accelerated GNN training and inference [18] |

Advanced Technical Support

Advanced Configuration and Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How can I optimize GEMNA parameters for specific types of metabolomic studies? A: Parameter optimization should be guided by your experimental design. For untargeted metabolomics with extensive coverage, focus on sensitivity settings. For targeted approaches with specific metabolic pathways, adjust embedding dimensions to prioritize known biological relationships. The tool provides configuration templates for different study types [18] [5].

Q: Can GEMNA integrate with existing metabolomic workflows and databases? A: Yes, GEMNA is designed for interoperability. It can accept output from common MS processing pipelines and connect with metabolic databases such as MetLin and mzCloud for enhanced metabolite annotation, as demonstrated in the leaf dataset experiments [18].

Q: How does GEMNA handle batch effects in multi-center studies? A: GEMNA's embedding approach naturally handles technical variability through its anomaly detection algorithms. For pronounced batch effects, we recommend pre-processing with standard normalization techniques before graph construction, similar to approaches used in the cross-hospital validation of DeepMSProfiler [34].

Troubleshooting Guide

Q: The anomaly detection is filtering out too many potentially interesting signals.

- Issue: Overly conservative anomaly detection thresholds.

- Solution: Adjust the sensitivity parameters in the configuration file, or implement a tiered approach that allows for manual review of borderline signals before final exclusion [18].

Q: I'm experiencing convergence issues during model training.

- Issue: Unstable training dynamics or inappropriate learning rates.

- Solution: Reduce the learning rate, implement gradient clipping, or increase batch size. Monitor training logs for signs of divergence and consult the example configurations provided [5].

Q: The network visualizations are too dense to interpret meaningfully.

- Issue: High connectivity in metabolic networks creating visual complexity.

- Solution: Use hierarchical clustering before visualization, implement edge filtering based on correlation strength, or focus on subnetworks of biological interest using GEMNA's modular analysis features [33].

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: Why are my metabolic networks too dense and uninterpretable after constructing them from correlation data?

- Problem: The resulting graph is a "hairball," hindering the identification of meaningful biological modules.

- Solution: This is often due to an improperly set correlation threshold.

- Action: Systematically test different correlation coefficient (e.g., Pearson or Spearman) and statistical significance (p-value) thresholds. Use a positive control, like a known metabolic pathway, to guide your threshold selection. A higher correlation coefficient and a lower p-value (e.g., |r| > 0.8 and p < 0.01) will yield a sparser, more biologically relevant network [35].

- Prevention: Incorporate prior biological knowledge. Use a knowledge network from a database like BioCyc to constrain your experimental correlation network, focusing only on correlations between metabolites that are known to be biochemically related [35].

Q2: My graph embedding results are poor. How can I determine if the issue is with my graph construction or the embedding model itself?

- Problem: The node embeddings do not form meaningful clusters when visualized.

- Solution: Perform a stepwise diagnostic.

- First, validate your graph construction by using a simple, interpretable layout algorithm (like a force-directed layout) to visualize the raw graph before embedding. If the graph itself shows no clear structure, the problem lies in the graph construction phase [36].

- Second, if the graph structure appears sound, test the embedding on a downstream task like node classification or link prediction. Compare the performance of different embedding algorithms (e.g., Node2Vec vs. a Graph Neural Network) to see if the problem is model-specific [5] [37]. GNN-based models like GEMNA are often more robust as they can share parameters and utilize both node features and graph structure [5].

Q3: How can I integrate multiple types of relationships (e.g., correlations and structural similarities) into a single network for embedding?

- Problem: You have different experimental networks (correlation, spectral similarity) and want to combine them for a more powerful analysis.

- Solution: Construct a multi-layer network or a heterogeneous graph.

- Approach: In a heterogeneous graph, you can define different node and edge types [37]. For example, metabolites are nodes, but you can have multiple edge types such as "iscorrelatedwith" and "isstructurallysimilar_to." Advanced graph embedding techniques can then process this complex graph to create a unified representation [35]. Frameworks like MoMS-Net use heterogeneous graphs to incorporate relationships between molecules and their structural motifs, improving prediction performance [38].

Q4: What are the best practices for visualizing my network and embedding results to communicate findings effectively?

- Problem: The visualization is cluttered and fails to highlight key findings.

- Solution: Employ visual analytics strategies.

- For Networks: Use pathway collages or similar tools to create personalized multi-pathway diagrams. These allow you to manually curate the layout of key pathways and their interactions, providing a clear, publication-quality figure [39]. Tools like BatMass are also designed for fast, interactive visualization of MS data, helping you explore your data before graph construction [40].

- For Embeddings: Use dimensionality reduction techniques like UMAP or t-SNE to project your high-dimensional embeddings into a 2D or 3D scatter plot for visualization. Color the points by a property of interest (e.g., pathway membership, statistical significance) to reveal clusters and patterns [36] [4].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Quantitative Metrics for Graph and Embedding Evaluation

| Metric | Definition | Use Case in Metabolomics | Exemplary Value from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silhouette Score | Measures how similar a node is to its own cluster compared to other clusters (range: -1 to 1). | Validating the clustering quality of node embeddings. | GEMNA method: 0.409; Traditional approach: -0.004 on a Mentos candy dataset [5]. |

| Recall@k | The proportion of queries where the correct item is found in the top-k results. | Assessing compound identification accuracy from spectral embeddings. | LLM4MS achieved Recall@1: 66.3% and Recall@10: 92.7% on the NIST23 test set [4]. |

| Cosine Similarity | Measures the angular similarity between two vectors (e.g., predicted vs. actual spectrum). | Evaluating the accuracy of a mass spectrum prediction model. | MoMS-Net achieved superior cosine similarity vs. CNN, GCN, and MassFormer models on NIST data [38]. |

Detailed Methodology: Constructing a Correlation-Based Metabolic Network

This protocol outlines the steps to build a graph from untargeted MS data where metabolites are nodes and statistical correlations are edges [35].

- Data Pre-processing: Begin with your peak table from untargeted MS analysis. Ensure data has been normalized, missing values have been imputed, and any batch effects have been corrected.

- Correlation Calculation: Calculate pairwise correlation coefficients (e.g., Spearman's rank correlation) for all metabolites across all samples. Simultaneously, calculate the corresponding p-values for each correlation.

- Graph Construction:

- Nodes: Each metabolite (or MS1 feature) is represented as a node. Node attributes can include m/z, retention time, and average abundance.

- Edges: Create an edge between two nodes if their correlation meets a dual threshold: the correlation coefficient absolute value is above a set limit (e.g., |r| > 0.7) and the p-value is below a significance threshold (e.g., p < 0.05). The edge weight can be set to the correlation coefficient.

- Network Pruning (Optional): To reduce complexity, you can further prune the network by only keeping the top N strongest edges for each node.

- Export: Export the graph in a standard format (e.g., adjacency list, GML, or GraphML) for downstream analysis or embedding.

Workflow Diagram: From MS Data to Graph Embedding

Relationship Diagram: Types of Networks in Metabolomics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for Network Construction and Embedding