Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis (MSEA): A Comprehensive Guide for Pathway Discovery in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis (MSEA), a powerful bioinformatic method for interpreting metabolomic data by identifying biologically meaningful patterns in metabolic pathways.

Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis (MSEA): A Comprehensive Guide for Pathway Discovery in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis (MSEA), a powerful bioinformatic method for interpreting metabolomic data by identifying biologically meaningful patterns in metabolic pathways. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore MSEA's foundational principles, core methodologies like Overrepresentation Analysis (ORA) and Quantitative Enrichment Analysis (QEA), and its application across diverse research areas including inherited metabolic disorder diagnostics. The guide addresses critical practical considerations such as tool selection, data preprocessing, and identifier mapping, supported by comparative analysis of leading platforms like MetaboAnalyst. Finally, we examine validation strategies and future directions integrating multi-omics data, providing a complete framework for implementing MSEA to uncover functional insights in metabolic systems biology.

Understanding MSEA: From Basic Concepts to Biological Significance

What is MSEA? Defining Core Principles and Workflow

Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis (MSEA) represents a paradigm shift in metabolomic data interpretation, moving beyond single metabolite analysis to biologically meaningful pattern recognition. This technical guide examines MSEA's core principles, methodological frameworks, and implementation workflows that enable researchers to identify subtle but coordinated changes across metabolite groups. By leveraging curated metabolite set libraries and robust statistical approaches, MSEA facilitates the transformation of raw metabolomic data into functional insights for pathway discovery and biomarker research. We present comprehensive methodological protocols, visualization frameworks, and practical implementation guidelines to support researchers and drug development professionals in deploying MSEA effectively within their metabolomic studies.

Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis (MSEA) is a computational approach designed to help metabolomics researchers identify and interpret patterns of metabolite concentration changes in a biologically meaningful context [1]. Conceptually adapted from Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) in transcriptomics, MSEA addresses fundamental challenges in metabolomic data interpretation by shifting the analytical focus from individual metabolites to predefined groups of functionally related metabolites [2]. This approach recognizes that biologically significant changes often manifest as coordinated alterations across multiple metabolites within specific pathways, disease states, or location-based sets, even when individual metabolite changes are modest or statistically marginal.

The fundamental premise of MSEA rests on detecting non-random, collective behaviors among metabolites that share biological context, thereby providing functional interpretation for metabolomic findings [2]. Unlike conventional univariate analyses that treat metabolites as independent entities, MSEA incorporates prior biological knowledge through curated metabolite sets, enabling researchers to determine whether metabolites associated with particular pathways or diseases appear more frequently in their experimental data than expected by chance [1]. This methodology has proven particularly valuable for interpreting results from both targeted and untargeted metabolomic studies, serving as a critical bridge between raw analytical data and biological insight.

MSEA was initially developed to address several limitations inherent in traditional metabolomic analysis approaches [2]. Conventional methods typically involve selecting significant metabolites using arbitrary thresholds (e.g., p-values or fold-change cutoffs), which can miss moderate but biologically coordinated changes. Additionally, manual interpretation of metabolite lists is time-consuming and subject to researcher bias. MSEA systematically addresses these limitations by evaluating predefined metabolite sets as integrated units, preserving biological context, and employing statistically rigorous enrichment measures that consider the interconnected nature of metabolic networks.

Core Principles of MSEA

Conceptual Foundation

MSEA operates on several foundational principles that distinguish it from conventional metabolite-by-metabolite analysis approaches. The methodology recognizes that biological processes typically affect multiple metabolites within related pathways simultaneously, creating "subtle but coordinated" changes that might escape detection when examining individual metabolites in isolation [2]. This systems-level perspective aligns with the understanding that cellular metabolism functions through interconnected networks rather than through independent biochemical reactions.

A second core principle involves leveraging accumulated biological knowledge through curated metabolite sets. Rather than treating metabolomic data as independent measurements, MSEA contextualizes results within established metabolic pathways, disease associations, and tissue locations [2]. This knowledge-based approach allows researchers to interpret their experimental findings within established biological frameworks, generating hypotheses about underlying mechanisms rather than merely reporting statistical associations.

The third foundational principle concerns statistical robustness through set-based testing. By evaluating groups of metabolites collectively, MSEA reduces the multiple testing burden associated with analyzing hundreds of individual metabolites and increases statistical power to detect pathway-level effects that might be missed when focusing on individual metabolites that fail to reach strict significance thresholds after multiple test correction [2].

Key Metabolite Set Libraries

The biological relevance of MSEA results depends critically on the quality and comprehensiveness of the underlying metabolite set libraries. These libraries organize metabolites into biologically meaningful groups based on different criteria:

- Pathway-associated sets: Contain metabolites known to participate in specific metabolic pathways. MSEA initially included 84 human metabolic pathways from the Small Molecular Pathway Database (SMPDB) [2], though contemporary implementations like MetaboAnalyst now support pathway analysis for over 120 species [3].

- Disease-associated sets: Include metabolites that show characteristic changes in specific disease states. These sets are typically biofluid-specific, recognizing that disease signatures manifest differently in blood, urine, and cerebral spinal fluid. The initial MSEA release contained 851 disease-associated sets [2].

- Location-based sets: Comprise metabolites preferentially found in specific tissues, cellular compartments, or biofluids. These sets help contextualize findings based on sample origin and can provide clues about tissue-specific metabolic regulation [2].

Table 1: Major Metabolite Set Libraries in MSEA

| Library Category | Initial Entries | Current Scope (MetaboAnalyst) | Primary Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway-associated | 84 human pathways | >120 species | SMPDB, KEGG, Reactome |

| Disease-associated | 851 sets | ~13,000 metabolite sets | HMDB, literature curation |

| Location-based | 57 sets | Included in broader collections | HMDB tissue/cellular localization |

| Biofluid-specific | 398 blood, 335 urine, 118 CSF | Expanded coverage | HMDB, MIC, PubMed |

Modern implementations like MetaboAnalyst have significantly expanded these collections, now offering approximately 13,000 biologically meaningful metabolite sets collected primarily from human studies, including over 1,500 chemical classes [3]. This expansion greatly enhances the biological contexts available for interpretation and enables more specialized investigations across diverse research domains.

MSEA Methodologies and Workflows

Overrepresentation Analysis (ORA)

Overrepresentation Analysis (ORA) represents the most straightforward MSEA approach, operating on a simple binary classification of metabolites as "interesting" or "not interesting" based on statistical thresholds [4]. The method requires three essential inputs: a collection of pathways or metabolite sets, a list of metabolites of interest (typically those showing significant changes in an experiment), and a background or reference set of compounds representing all metabolites detectable in the assay [4].

The statistical foundation of ORA employs Fisher's exact test based on the hypergeometric distribution to calculate the probability of observing at least k metabolites of interest in a pathway by chance [4]. The formula is expressed as:

Where:

- N = size of background set

- n = number of metabolites of interest

- M = number of metabolites in the background set mapping to a specific pathway

- k = number of metabolites of interest mapping to that pathway

Critical considerations for ORA implementation include background set specification, which significantly impacts results. Using generic, non-assay-specific background sets can produce large numbers of false-positive pathways, while assay-specific background sets (containing only compounds identifiable with the specific analytical platform) yield more reliable outcomes [4]. Additional factors such as pathway database selection (KEGG, Reactome, BioCyc), metabolite identification reliability, and analytical platform chemical bias further influence ORA results, necessitating careful parameter selection and transparent reporting [4].

Quantitative Enrichment Analysis (QEA)

Quantitative Enrichment Analysis (QEA) represents a more sophisticated MSEA approach that incorporates concentration information rather than simply using binary membership [2]. This method addresses a key limitation of ORA by preserving the magnitude of metabolite changes, thereby increasing sensitivity to detect subtle but coordinated alterations across pathway members.

QEA operates on concentration tables from quantitative metabolomics studies, typically comparing two or more experimental conditions [5]. The methodology involves calculating enrichment scores for each metabolite set that incorporate both the direction and magnitude of concentration changes, then assessing statistical significance through permutation testing to account for set size and correlation structure among metabolites [2].

This approach proves particularly valuable when individual metabolite changes are modest but consistently directional within pathways, situations where ORA might lack statistical power. QEA also reduces the arbitrary threshold selection inherent in ORA, as it doesn't require pre-selection of "significant" metabolites based on potentially arbitrary p-value or fold-change cutoffs [2].

Single Sample Profiling (SSP)

Single Sample Profiling (SSP) extends MSEA to individual sample characterization, enabling researchers to evaluate pathway-level activity in each experimental unit rather than only at the group level [2]. This approach calculates pathway activity scores for individual samples based on metabolite concentrations, facilitating patient stratification, biomarker validation, and personalized interpretation.

SSP implementation requires reference concentration ranges for metabolites, typically obtained from databases like the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB) [2]. Each sample's metabolite profile is compared against these reference ranges to generate deviation scores that are aggregated at the pathway level, creating individualized pathway activation measures.

This method proves particularly valuable in clinical applications, where inter-individual variability is significant, and in temporal studies tracking pathway dynamics across different conditions or timepoints. SSP enables researchers to move beyond group averages to understand pathway-level heterogeneity within sample populations.

Experimental Design and Implementation

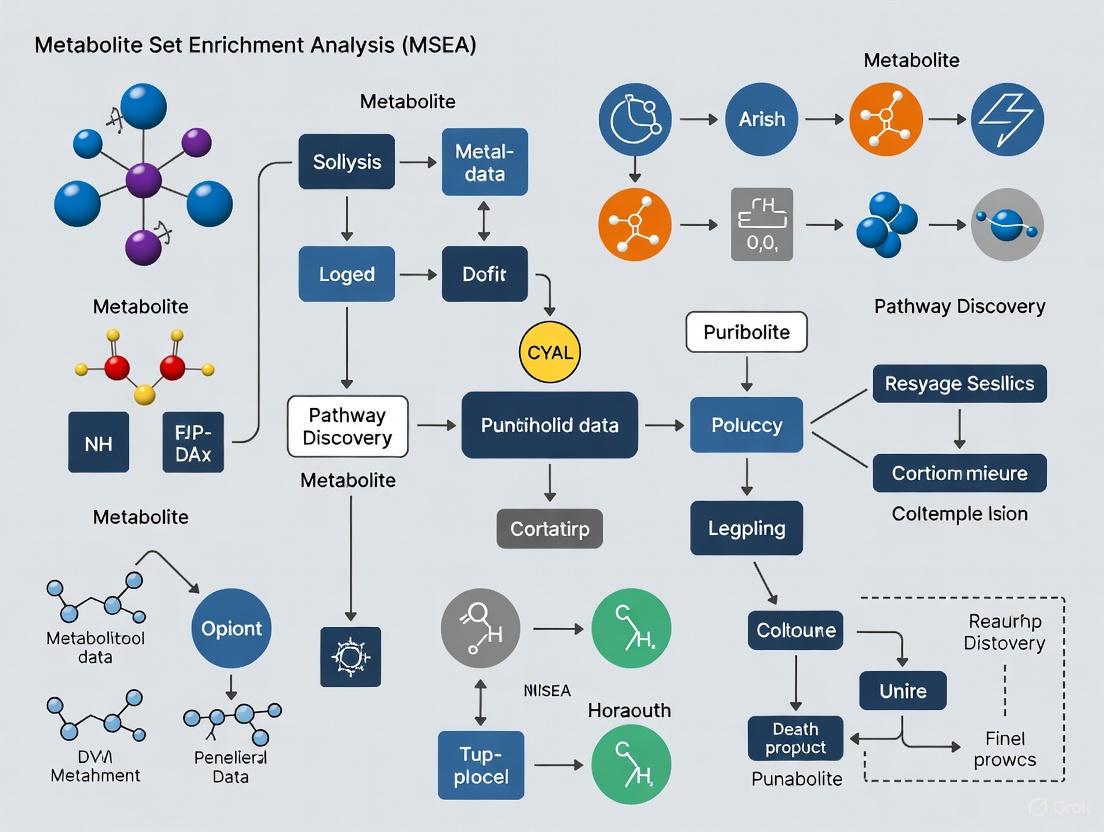

Implementing MSEA requires careful experimental planning and execution across three primary stages: data collection, data processing, and enrichment analysis. The following workflow diagram illustrates the key decision points and methodological pathways in a comprehensive MSEA investigation:

Input Data Requirements and Preparation

Successful MSEA implementation requires appropriate data formatting and preprocessing. The specific requirements vary by methodology but share common elements:

For Overrepresentation Analysis, the primary input is a list of compound names or identifiers representing metabolites showing significant changes in the experiment [5]. This list typically derives from statistical tests comparing experimental conditions, with metabolites selected based on p-value thresholds, fold-change criteria, or multivariate importance measures.

For Quantitative Enrichment Analysis and Single Sample Profiling, the input consists of a concentration table with metabolites as rows and samples as columns, accompanied by experimental metadata defining group membership or experimental conditions [5]. Data preprocessing typically includes normalization, missing value imputation, and sometimes transformation to approximate normal distributions.

A critical step across all MSEA methods is compound cross-referencing, where metabolite identifiers from the experimental data are mapped to standardized names or database identifiers used in the metabolite set libraries [2]. This process resolves synonyms, alternate naming conventions, and platform-specific identifiers to ensure proper mapping to biological pathways. Modern MSEA platforms support conversions between common names, synonyms, and identifiers from major metabolomic databases including HMDB, PubChem, ChEBI, KEGG, BiGG, METLIN, BioCyc, Reactome, and others [2].

Implementing MSEA effectively requires access to specialized databases, analytical tools, and computational resources. The following table summarizes key components of the MSEA research toolkit:

Table 2: Essential Resources for Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway Databases | KEGG, Reactome, BioCyc, SMPDB | Provide curated metabolic pathways | Species-specific coverage, differential annotation focus |

| Metabolite Databases | HMDB, PubChem, ChEBI, METLIN | Metabolite identification and standardization | Cross-reference capabilities, concentration data |

| Enrichment Analysis Platforms | MetaboAnalyst, MSEA Server, MeltDB | Perform enrichment calculations | Multiple methods, intuitive interfaces, visualization |

| Statistical Frameworks | R, Python with specialized packages | Data preprocessing and statistical analysis | Custom analysis pipelines, advanced visualization |

| Analytical Platforms | LC-MS, GC-MS, NMR, CE-MS | Metabolite separation and detection | Differential coverage, sensitivity, quantitative accuracy |

Computational Implementation and Visualization

Practical Implementation Guide

The computational implementation of MSEA involves several sequential steps, from data input through to results interpretation. The following diagram illustrates the core analytical workflow implemented in platforms like MetaboAnalyst:

For ORA implementation, researchers must carefully select the background set appropriate for their analytical platform [4]. For targeted metabolomics, this includes all compounds assayed; for untargeted approaches, it comprises all annotatable metabolites detected. Using generic, non-assay-specific background sets (e.g., all metabolites in an organism's metabolome) can produce large numbers of false-positive pathways because the test incorrectly assumes non-detected metabolites could have been measured but weren't significant [4].

Multiple testing correction represents another critical step, with false discovery rate (FDR) methods like Benjamini-Hochberg typically applied to account for the simultaneous evaluation of numerous metabolite sets. The threshold for significance (commonly FDR < 0.05 or 0.1) should be selected based on the study's goals—more stringent thresholds for confirmatory studies, less stringent for exploratory investigations.

Results Interpretation and Visualization

Effective interpretation of MSEA results requires both statistical and biological reasoning. Key outputs typically include:

- Enrichment scores or p-values: Quantitative measures of whether metabolites in a particular set show more coordinated changes than expected by chance.

- Pathway impact values: Metrics incorporating topological information about the relative importance of changed metabolites within pathways.

- Visualization displays: Bar plots, dot plots, network diagrams, and pathway maps that facilitate intuitive understanding of results.

Successful interpretation requires considering both statistical significance and biological relevance. Pathways with strong statistical support should be evaluated in the context of existing literature and experimental design. Researchers should also examine the consistency of changes within pathways—whether metabolites show directional concordance (e.g., most intermediates in a pathway increasing together) and whether changes align with known regulatory mechanisms.

Comparative visualization across multiple experimental conditions can reveal condition-specific pathway alterations and help prioritize findings for further investigation. Integration with other omics data (transcriptomics, proteomics) through joint pathway analysis or network approaches can further enhance biological interpretation and mechanistic insight [3].

Best Practices and Methodological Considerations

Critical Parameter Selection

Robust MSEA implementation requires careful attention to several methodological parameters that significantly impact results:

Background set specification: As highlighted in [4], using assay-specific background sets rather than comprehensive metabolome lists reduces false positives. The background should represent only metabolites detectable with the specific analytical platform employed in the study.

Pathway database selection: The choice of pathway database (KEGG, Reactome, BioCyc, etc.) profoundly influences results, as different databases have varying coverage, organization, and annotation focus [4]. Researchers should consider database relevance to their experimental organism and research question, and potentially compare results across databases to identify robust findings.

Metabolite of interest selection: For ORA, the criteria for selecting "significant" metabolites from the larger dataset requires careful consideration. While p-value thresholds are common, complementary approaches using fold-change thresholds or multivariate importance measures may provide complementary perspectives.

Organism-specific pathway sets: Whenever possible, using organism-specific rather than generic pathway sets improves biological relevance and reduces false positives from mapping metabolites to pathways not present in the studied organism [4].

Reporting Standards and Quality Control

Transparent reporting of MSEA parameters enables proper evaluation and reproducibility. Key reporting elements include:

- Analytical platform description and detection limitations

- Compound identification confidence levels

- Background set composition and justification

- Pathway database version and source

- Metabolite selection criteria and thresholds

- Multiple testing correction method

- Software tools and versions used

Quality control measures should address metabolomics-specific challenges such as metabolite misidentification and analytical platform chemical bias. [4] demonstrated that simulated metabolite misidentification rates as low as 4% can produce both false-positive pathways and loss of truly significant pathways. Rigorous compound identification protocols and platform-specific bias awareness are therefore essential for reliable MSEA results.

Recent methodological recommendations emphasize using assay-specific background sets, validating findings with multiple pathway databases, reporting metabolite identification confidence levels, and applying multiple testing correction appropriate for the study design [4]. These practices enhance the reliability and interpretability of MSEA results, facilitating more meaningful biological insights from metabolomic studies.

Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis represents a powerful framework for extracting biological meaning from complex metabolomic datasets. By shifting the analytical focus from individual metabolites to biologically coherent sets, MSEA enables researchers to identify functional patterns that might otherwise remain obscured in metabolite-by-metabolite analyses. The core methodologies—Overrepresentation Analysis, Quantitative Enrichment Analysis, and Single Sample Profiling—offer complementary approaches suitable for different experimental designs and data types.

Successful implementation requires careful attention to methodological details including background set specification, pathway database selection, and appropriate statistical thresholds. As the field advances, standardization of reporting practices and continued refinement of metabolite set libraries will further enhance the utility and reliability of MSEA for pathway discovery and functional interpretation in metabolomics.

For researchers and drug development professionals, MSEA offers a robust analytical bridge between raw metabolomic measurements and biological insight, supporting hypothesis generation, biomarker discovery, and mechanistic understanding in diverse research domains from basic science to clinical translation.

Enrichment analysis has undergone a significant evolution from its genomic origins to become an indispensable tool in metabolomics research. This transformation has been driven by the unique challenges of metabolite annotation and identification in untargeted metabolomics, necessitating specialized approaches that shift the unit of analysis from individual metabolites to biologically meaningful metabolite sets. This technical review examines the conceptual and methodological foundations of metabolite set enrichment analysis (MSEA), detailing its applications in pathway discovery, biomarker identification, and drug development. We provide comprehensive experimental protocols, comparative performance assessments of popular algorithms, and essential resource guidelines to equip researchers with practical frameworks for implementing MSEA in their investigative workflows. The integration of MSEA with other omics technologies and artificial intelligence represents the next frontier in systems biology approaches to pharmaceutical research and personalized medicine.

The paradigm of enrichment analysis originated in genomics with the development of Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA), which revolutionized the interpretation of high-throughput gene expression data by focusing on coordinated changes in functionally related gene sets rather than individual genes. This approach successfully addressed the challenges of multiple testing corrections and subtle but coordinated biological effects that might be missed when examining single genes. The conceptual framework proved so powerful that it naturally extended to other omics fields, including metabolomics, though with significant methodological adaptations required to address the unique characteristics of metabolic data [6].

The migration of enrichment analysis from genomics to metabolomics represents more than a simple substitution of analytical entities—it requires fundamental rethinking of statistical approaches, annotation challenges, and biological interpretation. While genomics benefits from well-annotated reference genomes and relatively straightforward identification of gene products, metabolomics faces substantial hurdles in metabolite identification and annotation. Untargeted metabolomics experiments typically detect thousands of metabolic features, only a fraction of which can be confidently identified, creating a critical bottleneck for biological interpretation [7] [6]. This challenge prompted the development of approaches that could extract biological meaning from partially annotated datasets.

Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis (MSEA) emerged as a solution to this problem by shifting the analytical focus from individual metabolites to functionally related groups. The fundamental premise is that while individual metabolite identifications may be uncertain, the collective behavior of metabolites within known biological pathways or chemical classes provides more robust evidence of pathway perturbation [8]. This approach mirrors the philosophy behind GSEA but incorporates metabolome-specific considerations, including extensive chemical diversity, rapid metabolic turnover, and the immediate reflection of physiological status that characterizes the metabolome [9].

The institutionalization of MSEA within widely adopted platforms like MetaboAnalyst, which provides access to approximately 13,000 biologically meaningful metabolite sets collected primarily from human studies, has dramatically accelerated its adoption in pharmaceutical research and disease mechanism investigation [3]. This evolution from genomic to metabolic enrichment analysis represents a crucial advancement in systems biology, enabling researchers to capture the functional output of complex biological systems and potentially bridging the gap between genotype and phenotype.

Methodological Approaches in Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis

Core Algorithms and Their Theoretical Foundations

The statistical framework for MSEA has evolved to address the specific characteristics of metabolomic data, resulting in three predominant methodological approaches: Over-Representation Analysis (ORA), Functional Class Scoring (including MSEA proper), and topology-based methods. Each approach employs distinct algorithms and makes different assumptions about the underlying data structure.

Over-Representation Analysis (ORA) represents the simplest approach, conceptually borrowed from transcriptomics. ORA begins with a list of metabolites statistically different between experimental conditions, typically based on fold-change and p-value thresholds. This metabolite list is then tested for disproportionate representation in predefined metabolite sets using statistical methods like Fisher's exact test. The primary limitation of ORA is its dependence on arbitrary thresholds for declaring significance and its disregard for the magnitude and direction of metabolic changes [7]. Despite these limitations, ORA remains widely used for its conceptual simplicity and straightforward interpretation.

Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis (MSEA proper) applies a functional class scoring approach that overcomes many ORA limitations by considering the entire ranked list of metabolites rather than applying arbitrary significance thresholds. The algorithm ranks all detected metabolites based on their differential expression or correlation with phenotypes, then tests for uneven distribution of predefined metabolite sets within this ranked list using Kolmogorov-Smirnov-like running sum statistics. This approach captures subtle but coordinated changes across multiple metabolites within a pathway, making it particularly suitable for detecting moderate changes affecting multiple pathway components [10] [3].

Mummichog represents a paradigm shift specifically designed for untargeted metabolomics. This algorithm bypasses the need for complete metabolite identification by leveraging the collective power of metabolic pathways and network topology. Mummichog predicts pathway activity directly from spectral features by testing the enrichment of empirically defined modules within a metabolic network [8]. This approach has demonstrated particular effectiveness for high-resolution mass spectrometry data, where comprehensive metabolite identification remains challenging. A recent comparative study evaluating enrichment methods for untargeted in vitro metabolomics found that Mummichog outperformed both MSEA and ORA in terms of consistency and correctness [7].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Metabolite Enrichment Methodologies

| Method | Statistical Approach | Data Requirements | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Over-Representation Analysis (ORA) | Fisher's exact test or hypergeometric test | List of significant metabolites | Simple implementation and interpretation | Depends on arbitrary significance thresholds; ignores magnitude of change |

| Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis (MSEA) | Kolmogorov-Smirnov-like running sum statistic | Full ranked list of metabolites | Captures subtle coordinated changes; no arbitrary thresholds | Requires confident metabolite identification for ranking |

| Mummichog | Empirical permutation testing of network modules | LC-MS peak lists with m/z and retention time | Bypasses need for complete identification; leverages pathway topology | Limited to predictable metabolic pathways; performance varies by organism |

Experimental Design and Performance Considerations

The choice of enrichment methodology depends heavily on experimental objectives, data quality, and annotation completeness. Studies utilizing targeted metabolomics approaches with comprehensive metabolite identification may benefit from MSEA proper, which fully leverages quantitative information across the entire metabolome. In contrast, untargeted studies with limited identification rates may achieve better performance with Mummichog, which specifically addresses the identification gap [7].

The 2025 comparative study examining enrichment methods for untargeted in vitro metabolomics provided critical insights for method selection. This systematic evaluation treated Hep-G2 cells with 11 compounds having different mechanisms of action and compared three popular enrichment approaches. The findings revealed low to moderate similarity between different enrichment methods, with the highest similarity observed between MSEA and Mummichog. Most significantly, Mummichog demonstrated superior performance in both consistency and correctness for in vitro untargeted metabolomics data [7].

Performance optimization also requires careful consideration of statistical parameters. The false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple testing represents a critical step, with Benjamini-Hochberg FDR correction being widely adopted to maintain balance between discovery of true positive findings and control of false positives [10] [6]. Additionally, the selection of appropriate metabolite set libraries significantly impacts results, with researchers able to choose from disease-associated metabolite sets, chemical class sets, or pathway-oriented collections depending on their research questions [10] [3].

Practical Implementation: Protocols and Workflows

Standardized MSEA Protocol for Disease Biomarker Discovery

The application of MSEA to identify and interpret patterns of human metabolite concentration changes associated with potential diseases follows a structured workflow that maximizes biological insight while maintaining statistical rigor. Based on established protocols, the following steps provide a reproducible framework for disease biomarker discovery:

Step 1: Data Preparation and Preprocessing Begin with raw data conversion to open formats (mzML, mzXML, or mzData) using tools like MSConvert (ProteoWizard). Subsequent feature detection and alignment should be performed using processing tools such as XCMS [6]. The data should then be formatted appropriately for MSEA, which can accept either a list of compound names, a list of compound names with concentrations, or a complete concentration table [3].

Step 2: Aberrant Feature Detection Employ statistical comparisons to identify features significantly differing between experimental conditions. For disease studies, this typically involves comparing patient samples to healthy controls using appropriate statistical tests (t-tests, ANOVA) with Benjamini-Hochberg FDR correction (α < 0.05) to account for multiple testing while maintaining sensitivity [6].

Step 3: Metabolite Annotation and Identification Estimate neutral masses by correcting feature m/z values for common adducts (mH+, mNa+, mH−, mCl−) in respective ion modes. Assign putative metabolite annotations by searching comprehensive databases such as HMDB (containing >114,000 metabolites) and KEGG (containing ~18,000 metabolites) with a mass tolerance of ≤5 ppm [6]. Note that this typically yields multiple putative annotations per feature (mean = 2.31; SD = 2.39), which MSEA accommodates through its set-based approach.

Step 4: Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis Execute MSEA using established platforms like MetaboAnalyst, selecting appropriate metabolite set libraries relevant to the research question. For blood-based disease studies, the library of disease-associated metabolite sets in blood (containing 416 metabolite sets reported in human blood) provides particularly relevant biological context [10]. The analysis tests for coordinated changes in predefined metabolite sets using statistical methods that account for the hierarchical structure of metabolic pathways.

Step 5: Results Interpretation and Validation Interpret enriched pathways in the context of known disease mechanisms, using FDR-corrected p-values (q-values) to prioritize statistically robust findings [10]. Implement validation strategies that may include independent sample sets, orthogonal analytical approaches, or integration with other omics data to confirm biological relevance.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and decision points in a standard MSEA workflow:

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research and Development

Drug Discovery and Development Pipeline

Metabolomics and MSEA have become integral components throughout the pharmaceutical research and development pipeline, from early target discovery to post-marketing surveillance. The ability to capture the immediate cellular state through metabolite profiling provides real-time insights into an organism's functional status that complements other omics technologies [9]. In early drug discovery, MSEA facilitates systematic identification of disease-specific metabolic signatures and validation of novel therapeutic targets through comprehensive analysis of pathway alterations in response to drug compounds [9] [11].

The value of MSEA is particularly evident in toxicology studies, where it enables early detection of drug-induced toxicity through comprehensive metabolic profiling. By identifying specific toxicological biomarkers and pathway perturbations, researchers can better predict safety profiles for drug candidates before advancing to clinical trials [9]. This application has been enhanced through the development of specialized metabolite set libraries focused on toxicity pathways and adverse outcome pathways.

In clinical development, MSEA provides critical insights for patient stratification based on metabolic response patterns and advanced monitoring of drug efficacy and safety [9] [12]. For instance, clinical metabolomics has demonstrated particular value in oncology, where it has revealed biomarkers crucial for predicting treatment outcomes and optimizing patient-specific therapeutic strategies [9]. The integration of MSEA with pharmacokinetic data further enables researchers to correlate changes in metabolic pathways with drug exposure levels, potentially informing dosing optimization.

Biomarker Discovery and Personalized Medicine

MSEA has revolutionized biomarker discovery by enabling the identification of metabolic pathway signatures rather than individual metabolite biomarkers. This approach captures the systemic nature of disease processes and drug responses, which frequently involve coordinated changes across multiple interconnected pathways [6]. In inherited metabolic disorders (IMDs), for example, MSEA has demonstrated value in prioritizing relevant biological pathways in untargeted metabolomics data, complementing feature-based prioritization by placing features in biological context [6].

The application of MSEA to personalized medicine represents one of the most promising developments in the field. By analyzing metabolites in patient samples, clinicians can identify metabolic subtypes of disease and develop targeted interventions specific to each patient's unique metabolic profile [11]. This approach enables treatment adjustment when patients show inadequate response to particular drugs based on their metabolomic profiles, potentially improving efficacy and safety while reducing healthcare costs [9] [11].

Table 2: Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis Applications in Drug Development

| Development Phase | Primary Application | Key MSEA Contribution | Example Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Discovery | Identification of disease-associated pathway perturbations | Reveals metabolic pathways significantly altered in disease | Prioritization of novel therapeutic targets based on pathway significance |

| Preclinical Development | Mechanism of action studies and toxicity assessment | Identifies pathways modulated by drug treatment and toxicity pathways | Prediction of drug efficacy and safety through pathway analysis |

| Clinical Trials | Patient stratification and response monitoring | Discovers metabolic signatures differentiating treatment responders from non-responders | Development of companion diagnostics based on metabolic pathway profiles |

| Post-Marketing | Drug repurposing and safety monitoring | Identifies novel pathway indications for existing drugs | Discovery of new therapeutic applications through shared pathway modulation |

Successful implementation of MSEA requires both experimental reagents for metabolite profiling and computational resources for data analysis and interpretation. The following toolkit represents essential resources for researchers in the field:

Analytical Platforms and Databases

Mass Spectrometry Platforms form the foundation of metabolomic data generation. High-resolution instruments such as the timsTOF Pro (Bruker) coupled with UHPLC systems provide the sensitivity and resolution needed for comprehensive metabolite profiling [7]. These platforms generate the raw spectral data that undergo preprocessing before MSEA.

Metabolite Databases are indispensable for metabolite annotation and identification. The Human Metabolome Database (HMDB) contains over 114,000 metabolite entries, while KEGG provides approximately 18,000 metabolite entries with rich pathway information [6]. These databases enable the translation of spectral features into biological entities.

Pathway Databases provide the organizational framework for enrichment analysis. The Small Molecule Pathway Database (SMPDB) offers 894 primary pathways with particular strength in inherited metabolic diseases, while KEGG contains 317 human pathways with broader coverage of metabolic processes [6]. Specialized libraries containing approximately 13,000 biologically meaningful metabolite sets further enhance interpretation [3].

Computational Tools and Software

MetaboAnalyst represents the most comprehensive web-based platform for MSEA, supporting both statistical and functional analysis of metabolomics data [3]. The platform provides user-friendly access to multiple enrichment algorithms, including MSEA, Mummichog, and ORA, along with extensive visualization capabilities. Recent enhancements include enrichment networks for exploring pathway analysis results and joint pathway analysis integrating gene and metabolite data [3].

MetaboAnalystR provides programmatic access to the complete MetaboAnalyst functionality within the R environment, enabling automated, reproducible analysis and customization beyond the web interface [8]. The package implements an optimized LC-MS/MS workflow from raw spectral processing to functional interpretation, addressing key bioinformatics bottlenecks in global metabolomics.

XCMS remains a widely adopted tool for metabolomic data preprocessing, including feature detection, retention time alignment, and peak grouping [6]. Integrated within the MetaboAnalyst ecosystem, it provides robust data reduction from raw spectra to feature tables ready for statistical analysis and enrichment testing.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MSEA Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Key Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Platforms | UHPLC-timsTOF Pro, Orbitrap systems | High-resolution metabolite separation and detection | Commercial purchase from instrument vendors |

| Metabolite Databases | HMDB, KEGG, LipidMaps | Metabolite identification and annotation | Publicly available online databases |

| Pathway Resources | SMPDB, KEGG PATHWAY, Custom metabolite sets | Biological context for enrichment analysis | Integrated within analysis platforms or standalone |

| Analysis Software | MetaboAnalyst, MetaboAnalystR, XCMS | Data processing, statistical analysis, and enrichment testing | Web-based platform or R package installation |

Future Perspectives and Emerging Trends

The evolution of enrichment analysis continues with several emerging trends that promise to enhance its applications in metabolomics and systems pharmacology. Multi-omics integration represents a particularly promising direction, with platforms like MetaboAnalyst already supporting joint pathway analysis by uploading both gene lists and metabolite/peak lists for common model organisms [3]. This integration enables researchers to identify concordant pathway perturbations across multiple molecular layers, providing more comprehensive insights into biological mechanisms and drug actions.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are increasingly being applied to metabolomic data interpretation, enhancing complex pattern recognition in large-scale metabolomic datasets [9]. These approaches complement traditional MSEA by identifying novel metabolic patterns that may not be captured by predefined metabolite sets, potentially leading to the discovery of previously unrecognized metabolic regulatory mechanisms.

Advanced visualization techniques are evolving to address the complexity of enrichment results. Recent MetaboAnalyst updates include enrichment networks for exploring pathway analysis results, enabling researchers to identify modules of interconnected enriched pathways and potentially revealing higher-order biological organization [3]. These visualizations facilitate interpretation of complex metabolic remodeling in disease states and drug responses.

The methodological refinement of enrichment algorithms continues, with recent comparative studies providing evidence-based guidance for method selection [7]. The demonstrated superiority of Mummichog for untargeted in vitro metabolomics suggests that algorithm performance is context-dependent, prompting increased attention to method benchmarking and potentially spurring the development of next-generation algorithms that combine the strengths of existing approaches while addressing their limitations.

The evolution of enrichment analysis from its genomic origins to sophisticated metabolomic applications represents a paradigm shift in how researchers extract biological meaning from complex molecular data. Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis has emerged as an indispensable approach for interpreting metabolomic profiles in pharmaceutical research, disease mechanism investigation, and biomarker discovery. By focusing on coordinated changes in functionally related metabolite sets rather than individual metabolites, MSEA effectively addresses the fundamental challenge of incomplete metabolite identification that plagues untargeted metabolomics.

The continuing methodological refinements, expanding metabolite set libraries, and integration with other omics technologies ensure that MSEA will remain at the forefront of metabolic pathway analysis. As metabolomics continues to transform drug development by providing deeper insights into drug metabolism, toxicity mechanisms, and therapeutic efficacy, MSEA will play an increasingly critical role in translating complex metabolomic data into actionable biological insights. The ongoing evolution of enrichment analysis methodologies promises to further unlock the potential of metabolomics in personalized medicine and systems pharmacology, ultimately contributing to the development of safer, more effective, and precisely targeted therapeutic interventions.

Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis (MSEA) is a powerful method for interpreting metabolomic data by identifying biologically meaningful patterns through predefined sets of metabolites. Conceptually similar to Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) in transcriptomics, MSEA helps researchers determine whether groups of functionally related metabolites show statistically significant, coordinated changes between experimental conditions [2] [1]. This guide details the three core enrichment analysis approaches offered by the pioneering MSEA platform: Overrepresentation Analysis (ORA), Single Sample Profiling (SSP), and Quantitative Enrichment Analysis (QEA) [2].

The fundamental goal of MSEA is to overcome key limitations in conventional metabolomic data analysis, which often relies on arbitrarily selecting significantly altered metabolites, potentially missing subtle but coordinated changes among biologically related metabolites [2]. By leveraging a curated library of metabolite sets—grouped by metabolic pathways, disease associations, or tissue locations—MSEA provides a systems biology perspective [2] [1].

The following workflow illustrates how the three core MSEA approaches integrate into a comprehensive metabolomic data analysis pipeline, from raw data input to biological interpretation:

Overrepresentation Analysis (ORA)

Methodology and Experimental Protocol

Overrepresentation Analysis (ORA) is the simplest and most straightforward enrichment method. It operates on a discrete list of metabolite names, typically those identified as statistically significant in a prior univariate analysis [2].

The standard ORA protocol involves:

- Input Preparation: Generate a list of metabolite names considered significantly altered (e.g., based on p-values from t-tests or VIP scores from PLS-DA). This is the "hit list."

- Background Definition: Define a reference list containing all metabolites that were detected and identified in the study.

- Statistical Testing: For each predefined metabolite set (e.g., a pathway from SMPDB), a hypergeometric test or Fisher's exact test is performed. This test calculates the probability (p-value) of observing the overlap between the "hit list" and the metabolite set by random chance, given the background list.

- Multiple Testing Correction: Apply corrections such as the False Discovery Rate (FDR) to the obtained p-values to account for the testing of multiple metabolite sets.

Strengths and Limitations

ORA is widely accessible due to its minimal data requirements. However, its major limitation is the dependency on an arbitrary significance threshold for creating the "hit list," which can cause researchers to miss meaningful biological signals from metabolites with moderate but coordinated changes [2].

Single Sample Profiling (SSP)

Methodology and Experimental Protocol

Single Sample Profiling (SSP) calculates an enrichment score for each metabolite set within every individual sample. This transforms the data matrix from the metabolite-level to the pathway-level, enabling new types of analyses [13].

The standard SSP protocol involves:

- Input Preparation: A data matrix with compound names and their concentrations in each sample is required.

- Reference Concentration Database: SSP utilizes a database of normal reference concentrations for metabolites (e.g., from the Human Metabolome Database) to contextualize the data [2].

- Pathway-Level Transformation: For each sample and each metabolite set, a score is computed reflecting whether the metabolite concentrations within that set are systematically higher or lower than the reference values. Methods for this transformation can include z-score-based approaches or GSEA-like methods such as ssGSEA or GSVA [13].

- Downstream Analysis: The resulting pathway-level matrix enables analyses like multi-group comparisons, pathway-based clustering of samples, and machine learning classification based on pathway activity [13].

Performance and Application

SSP overcomes the thresholding problem of ORA and allows for the identification of patient-specific or sample-specific pathway signatures. A 2022 benchmark study evaluating SSP methods on metabolomic data found that while GSEA-based methods (ssGSEA, GSVA) had higher recall, clustering-based methods offered higher precision at moderate-to-high effect sizes [13].

Quantitative Enrichment Analysis (QEA)

Methodology and Experimental Protocol

Quantitative Enrichment Analysis (QEA) is the most statistically powerful MSEA approach as it directly models the relationship between continuous metabolite concentration data and phenotypes of interest without dichotomizing the data [2] [14].

The standard QEA protocol involves:

- Input Preparation: A data matrix with compound names and their concentrations across all samples, along with a continuous or multi-class phenotype label (e.g., disease severity, time series data).

- Global Test Statistic: QEA uses a global test statistic, such as Goeman's global test, to assess whether the concentrations of all metabolites in a predefined set are jointly associated with the phenotypic outcome [14].

- Model Fitting: The test fits a generalized linear model for the phenotype using the concentrations of metabolites in the set as predictors. The null hypothesis is that none of the metabolites in the set are associated with the phenotype.

- Significance Assessment: A single p-value is calculated for the entire metabolite set, indicating whether the set as a whole shows a significant association with the phenotype.

Advanced Application

QEA is particularly valuable for detecting subtle effects distributed across multiple metabolites within a pathway, which might be insignificant when each metabolite is tested individually [14].

Comparative Analysis of MSEA Approaches

The table below provides a structured comparison of the three core MSEA approaches, highlighting their key characteristics, data requirements, and appropriate use cases.

| Feature | Overrepresentation Analysis (ORA) | Single Sample Profiling (SSP) | Quantitative Enrichment Analysis (QEA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Required Input | List of significant metabolite names [2] | Metabolite names and concentrations for each sample [2] | Metabolite names, concentrations, and phenotype data [2] [14] |

| Statistical Basis | Hypergeometric test / Fisher's exact test [2] | Sample-wise enrichment score (e.g., z-score, ssGSEA) [2] [13] | Global test (e.g., Goeman's test) for set-phenotype association [2] [14] |

| Key Advantage | Simple, intuitive, minimal data requirements [2] | Enables sample-specific pathway analysis and multi-group comparisons [13] | Highest power; uses full quantitative data without arbitrary thresholds [2] [14] |

| Main Limitation | Depends on arbitrary pre-selection threshold [2] | Requires a reference concentration database for some methods [2] | More complex; requires phenotype data [2] |

| Ideal Use Case | Initial, quick screening with limited data availability | Classifying samples or comparing >2 groups based on pathway activity [13] | Detecting subtle, coordinated changes in pathway metabolites related to a phenotype [14] |

Successful implementation of MSEA relies on a suite of computational and database resources. The following table details key reagents and their functions in enrichment analysis.

| Research Reagent / Resource | Function in MSEA | Key Characteristics / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolite Set Libraries | Predefined groups of metabolites serving as the basis for enrichment testing [2]. | - Pathway-based: e.g., 84 human pathways from SMPDB [2].- Disease-associated: Metabolites altered in specific diseases, categorized by biofluid (blood, urine, CSF) [2].- Location-based: Metabolites grouped by tissue or cellular location from HMDB [2]. |

| Metabolite Dictionary & ID Converter | Facilitates conversion between metabolite common names, synonyms, and database identifiers [2]. | Supports major database IDs (HMDB, KEGG, PubChem, ChEBI, etc.), crucial for mapping experimental data to pathway definitions [2]. |

| Reference Concentration Database | Provides contextually normal concentration ranges for metabolites, essential for SSP analysis [2]. | Data primarily compiled from the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB) through manual curation [2]. |

| sspa Python Package | A software toolkit providing implementations of various Single Sample Pathway Analysis methods [13]. | Includes methods like ssGSEA, GSVA, z-score, and PLAGE, benchmarked for metabolomics data [13]. |

| Web-Based MSEA Server | A freely accessible online platform for performing all three types of enrichment analysis [2] [1]. | Hosted at http://www.msea.ca; also integrated into the MetaboAnalyst suite for comprehensive analysis [2] [1]. |

Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis (MSEA) has emerged as a powerful bioinformatics technique for interpreting quantitative metabolomic data within a biologically meaningful context. Conceptually similar to Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) in transcriptomics, MSEA uses curated collections of predefined metabolite sets to help researchers identify significant and coordinated changes in metabolomic data that might otherwise remain undetected when examining individual metabolites [15] [1]. This approach addresses a critical need in metabolomics research by enabling the interpretation of metabolite concentration patterns in relation to known metabolic pathways, disease states, and biofluid or tissue locations. By leveraging prior knowledge about biologically coherent metabolite groupings, MSEA provides metabolic context that significantly enhances the interpretation of metabolomic studies, facilitating discoveries in biomedical research and drug development.

The fundamental principle underlying MSEA is that biologically relevant changes often manifest as subtle but coordinated alterations across groups of functionally related metabolites, rather than as dramatic changes in individual metabolites. By testing for the enrichment of specific metabolite sets within experimental data, researchers can identify overarching biological themes and functional patterns [15]. Over the past decade, MSEA has evolved from a standalone tool into an integrated component of comprehensive metabolomics platforms like MetaboAnalyst, which now offers three distinct enrichment analysis approaches: Overrepresentation Analysis (ORA), Single Sample Profiling (SSP), and Quantitative Enrichment Analysis (QEA) [1] [5]. These methodologies provide researchers with flexible options for different experimental designs and data types, making MSEA an indispensable tool for modern metabolomics research.

Essential Metabolite Set Libraries: Composition and Scope

Library Structure and Organization

Metabolite set libraries are systematically organized collections of biologically coherent metabolite groupings that serve as the foundational knowledge base for MSEA. These libraries categorize metabolites based on their participation in biochemical pathways, association with specific diseases, concentration in particular biofluids or tissues, chemical structural classes, and other biologically meaningful criteria [15] [1]. The structural organization of these libraries enables researchers to map experimental metabolomic data onto established biological contexts, thereby facilitating functional interpretation.

The composition of these libraries has expanded significantly since the initial development of MSEA. Early versions contained approximately 1,000 predefined metabolite sets, but current implementations in platforms like MetaboAnalyst now include approximately 13,000 biologically meaningful metabolite sets collected primarily from human studies, including over 1,500 chemical classes [3] [5]. This expansion reflects both the growing knowledge of metabolism and the increasing sophistication of metabolomic research. The libraries are hierarchically organized, allowing researchers to investigate metabolic patterns at different levels of biological specificity, from broad metabolic processes to highly specific biochemical transformations.

Table 1: Comprehensive Overview of Essential Metabolite Set Libraries

| Library Category | Source/Database | Number of Sets | Metabolite Coverage | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Pathways | KEGG, HMDB, SMPDB | ~100-500 pathways | Extensive coverage of primary and secondary metabolism | Pathway enrichment analysis and topological analysis |

| Disease Associations | HMDB, Literature | Hundreds of disease states | Disease-specific metabolite signatures | Biomarker discovery and mechanistic studies |

| Biofluid/Tissue Locations | HMDB, Experimental Data | Multiple biofluids and tissues | Tissue- and biofluid-specific metabolomes | Experimental design and sample origin studies |

| Chemical Classes | PubChem, HMDB | >1,500 classes | Structural and functional classifications | Chemical characterization and novelty assessment |

| Custom Metabolite Sets | User-defined | Unlimited | User-specified metabolites | Specialized and non-model organism studies |

Detailed Library Classifications and Composition

Metabolic Pathway Libraries form the core of MSEA resources, with KEGG and HMDB/SMPDB being the most widely utilized databases [16]. The KEGG pathway database for Homo sapiens (hsa) contains 345 pathways, with 281 containing compound information essential for metabolomic studies [16]. These pathways are systematically classified into major categories including Metabolism, Cellular Processes, Environmental Information Processing, and Genetic Information Processing. The metabolism category is further subdivided into carbohydrate, lipid, amino acid, nucleotide, and other specialized metabolic pathways, providing comprehensive coverage of human metabolic processes.

Disease-Metabolite Association Libraries have expanded dramatically through large-scale systematic studies. Recent research has linked 313 plasma metabolites to 1,386 diseases and 3,142 traits using data from 274,241 UK Biobank participants [17]. This atlas uncovered 52,836 metabolite-disease and 73,639 metabolite-trait associations, with the ratio of cholesterol to total lipids in large low-density lipoprotein particles emerging as the metabolite associated with the highest number of diseases (n=526) [17]. Such extensive disease-metabolite association libraries enable researchers to identify metabolic dysregulation patterns characteristic of specific pathological states.

Biofluid and Tissue-Specific Libraries provide critical context for interpreting metabolomic data based on sample origin. Different biofluids including serum, plasma, cerebrospinal fluid, saliva, feces, sweat, tears, urine, breast milk, and cervicovaginal secretions each contain specialized metabolomes reflective of their physiological functions and origins [18]. These libraries account for the substantial physiological variations in metabolite concentrations across different biological compartments, enabling more accurate interpretation of metabolomic data.

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Frameworks

Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis Workflows

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of MSEA Methodologies

| Method Type | Input Requirements | Statistical Approach | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overrepresentation Analysis (ORA) | List of compound names | Hypergeometric test, Fisher's exact test | Simple implementation, intuitive results | Requires arbitrary significance thresholds, ignores concentration data |

| Single Sample Profiling (SSP) | Compound names with concentrations | Sample-wise enrichment scores | Enables patient/dample stratification | Requires reference population data |

| Quantitative Enrichment Analysis (QEA) | Concentration table with sample groups | Globaltest, GlobalAncova, or SSGSEA | Utilizes full quantitative data, higher sensitivity | More complex implementation, larger sample size requirements |

The experimental workflow for MSEA begins with comprehensive data preprocessing and quality control. For ORA, researchers input a list of compound names that have been identified as statistically significant in their study. The platform then performs compound name mapping to standardize metabolite identifiers across different databases (HMDB, PubChem, KEGG, etc.), which is crucial for accurate set matching [5]. Any compounds without database matches are flagged for manual inspection and correction. The enrichment analysis then tests each predefined metabolite set for overrepresentation among the significant metabolites using statistical approaches such as the hypergeometric test or Fisher's exact test, with multiple testing correction to control false discovery rates.

For QEA, which utilizes concentration data from full metabolomic profiles, the workflow includes additional preprocessing steps. These include data integrity checks, missing value imputation (using methods such as quantile regression imputation of left-censored data or MissForest), data normalization (including options for log2 normalization and variance stabilizing normalization), and data scaling [3]. The enrichment analysis then examines whether the joint behavior of metabolites in a set is significantly associated with the phenotypic groups or experimental conditions, using statistical methods that consider both the magnitude and direction of change for all metabolites in the set.

Pathway Prediction for Novel Metabolites

Advanced computational approaches have been developed to predict pathway associations for newly identified metabolites. One methodology leverages structural features extracted from SMILES annotations, including 167 MACCSKeys (structural fingerprints) and 34 physical properties [19]. After preprocessing using Principal Component Analysis for dimensionality reduction, clustering algorithms including K-modes clustering (for categorical data) and K-prototype clustering (for mixed data types) group metabolites based on structural and physicochemical similarities [19]. The fundamental premise is that structurally similar metabolites likely participate in related metabolic pathways, enabling pathway prediction for novel metabolites with reported accuracy of 92% for known metabolites [19].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for MSEA

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application in MSEA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolite Databases | HMDB, PubChem, KEGG Compound | Chemical structure and property information | Metabolite identification and annotation |

| Pathway Databases | KEGG, SMPDB, Reactome | Pathway architecture and composition | Reference metabolite sets for enrichment testing |

| Analysis Platforms | MetaboAnalyst, MSEA Server, MeltDB | Data processing and statistical analysis | Enrichment analysis implementation and visualization |

| Structural Analysis | RDKit, CACTUS | Molecular descriptor generation | Structural similarity assessment for novel metabolites |

| Clustering Algorithms | K-modes, K-prototypes | Grouping of similar metabolites | Pathway prediction for unannotated metabolites |

Visualization and Data Interpretation Frameworks

Analytical Workflow for Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for conducting metabolite set enrichment analysis, integrating both experimental and computational approaches:

Pathway Prediction Methodology for Novel Metabolites

The following diagram outlines the computational approach for predicting metabolic pathways for newly identified or poorly annotated metabolites:

Advanced Applications and Integration in Biomedical Research

Integration with Multi-Omics Approaches

Modern MSEA has evolved beyond standalone metabolomic analysis to integrate with other omics technologies, creating powerful multi-omics frameworks for systems biology. MetaboAnalyst now supports joint pathway analysis by uploading both gene and metabolite lists for approximately 25 common model organisms, enabling true integration of transcriptomic and metabolomic data [3]. This integration provides more comprehensive insights into biological systems by capturing information flow from genes to proteins to metabolites. The platform also incorporates Mendelian randomization analysis through metabolomics-based genome-wide association studies (mGWAS), allowing researchers to test potential causal relationships between genetically influenced metabolites and disease outcomes [3]. These advanced capabilities position MSEA as a central component in multi-omics research strategies for identifying robust biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

The functional analysis module "MS Peaks to Pathways" in MetaboAnalyst extends MSEA to untargeted metabolomics data from high-resolution mass spectrometry, supporting more than 120 species [3]. This module operates on the principle that approximate annotation at the individual compound level can accurately identify functional activity at the pathway level based on collective, non-random metabolic behaviors. By leveraging algorithms such as mummichog or GSEA, this approach bypasses the need for complete metabolite identification, instead focusing on pattern recognition within the mass spectrometry data that corresponds to known pathway activities [3]. This capability significantly enhances the utility of untargeted metabolomics for functional interpretation and hypothesis generation.

Biomarker Discovery and Therapeutic Target Identification

MSEA plays a pivotal role in biomarker discovery and validation by contextualizing metabolite changes within established biological frameworks. Large-scale metabolome-phenome association studies have demonstrated that over half (57.5%) of metabolites show statistical variations from healthy individuals more than a decade before disease onset, highlighting the potential of metabolic biomarkers for early disease detection [17]. When combined with demographic information, machine-learning-based metabolic risk scores derived from top metabolite biomarkers have shown excellent classification performance (area under the curve > 0.8) for 94 prevalent and 81 incident diseases [17]. These findings underscore the clinical potential of metabolite-based biomarkers identified through enrichment analysis approaches.

The application of MSEA in therapeutic development extends to identifying essential metabolites in pathogens, as exemplified by research on Mycobacterium tuberculosis. By identifying genes essential for in vitro growth through transposon mutagenesis (5,126 unique mutants with disruptions in 2,246 unique genes), researchers identified 401 essential enzyme-encoding genes and their corresponding essential metabolites [20]. This approach has identified critical pathways including peptidoglycan, chorismate, and tetrapyrrole biosynthesis as targets for antimicrobial development [20]. The identification of essential metabolites and their structural mimics provides a rational strategy for drug discovery, exemplified by compounds such as JFD01307SC and L-methionine-S-sulfoximine that inhibit M. tuberculosis growth at micromolar concentrations [20].

Future Directions and Methodological Advancements

The field of metabolite set enrichment analysis continues to evolve with several promising directions for methodological advancement. Current research focuses on improving pathway prediction for metabolites that lack complete annotations, with structural similarity-based approaches achieving approximately 92% accuracy in linking known metabolites to their respective pathways [19]. As metabolomic technologies advance toward spatial metabolomics and single-cell metabolomics, MSEA approaches will need to adapt to increasingly complex data structures and analytical challenges. The integration of machine learning and artificial intelligence with metabolite set analysis holds particular promise for uncovering novel metabolic patterns and relationships that may not be captured by current knowledge-driven approaches.

Another significant frontier is the development of dynamic pathway analysis methods that can capture metabolic flux and temporal changes in pathway activity, moving beyond the current focus on steady-state metabolite concentrations. As multi-omics integration becomes more sophisticated, MSEA will increasingly function as a bridge between metabolomic data and other molecular profiling domains, providing unique insights into the functional outcomes of cellular regulation. These advancements will further solidify the role of metabolite set enrichment analysis as an indispensable tool for extracting biological meaning from complex metabolomic data, ultimately accelerating discoveries in basic research, clinical diagnostics, and therapeutic development.

Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis (MSEA) is a powerful computational method designed to interpret metabolomic data within a biologically meaningful context. Mirroring the principles of Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA), which revolutionized transcriptomic data interpretation, MSEA shifts the focus from analyzing individual metabolites to investigating coordinated changes in predefined groups of functionally related metabolites [2]. This approach addresses critical challenges in metabolomics, where conventional analysis often relies on arbitrarily selecting significantly altered metabolites, potentially missing subtle but consistent changes across a group of related metabolites that collectively indicate a biological perturbation [2]. MSEA overcomes this by incorporating biological knowledge through metabolite sets, enabling the identification of pathways, disease states, or location-specific changes that might otherwise remain undetected. By examining patterns across metabolite sets, MSEA provides a systems-level perspective that is essential for understanding the complex metabolic alterations underlying physiological and pathological processes, thereby playing an increasingly vital role in systems biology, biomarker discovery, and drug development [2].

Methodological Foundations of MSEA

MSEA operates on the core principle that meaningful biological phenomena often manifest as coordinated changes in a set of metabolites sharing common biological characteristics. The methodology relies on three primary analytical approaches, each tailored to different types of input data and research questions.

Overrepresentation Analysis (ORA)

Overrepresentation Analysis (ORA) is the most straightforward MSEA approach. It requires a simple list of compound names identified as significantly altered in a metabolomic study [2]. The method tests whether certain predefined metabolite sets are represented more frequently than expected by chance within this input list [21]. Typically, a hypergeometric test is employed to calculate the statistical significance of the overlap between the input metabolite list and each metabolite set in the library [2] [21]. After testing all sets, the resulting p-values are adjusted for multiple testing to control the false discovery rate. While ORA is simple and widely used, its limitation lies in depending on an arbitrary significance threshold for selecting the input metabolites and disregarding quantitative concentration changes [2].

Single Sample Profiling (SSP)

Single Sample Profiling (SSP) incorporates quantitative concentration data. Instead of analyzing a list of significant metabolites, SSP uses compound names and their corresponding concentrations from a single sample to create a metabolic profile [2]. This profile is then compared against reference concentration ranges for various metabolite sets. The reference concentrations, often obtained from databases like the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB), represent normal physiological levels in specific biofluids or tissues [2]. SSP evaluates how the sample's metabolite concentrations deviate from these reference ranges within the context of predefined pathways or disease states, providing a patient-specific or sample-specific functional interpretation.

Quantitative Enrichment Analysis (QEA)

Quantitative Enrichment Analysis (QEA) represents the most statistically powerful MSEA method, as it uses both compound identities and their concentration measurements across multiple samples in a study [2]. Unlike ORA, QEA does not require pre-selection of significant metabolites. Instead, it uses a rank-based test that considers the entire list of measured metabolites, ranked by the magnitude of their concentration changes or statistical importance (e.g., p-values from a t-test) [2]. An enrichment score is calculated for each metabolite set, reflecting the degree to which its members are concentrated at the top or bottom of the ranked list. The statistical significance of this score is determined by comparing it against a null distribution generated through phenotype permutation. This approach is particularly effective for detecting modest but coordinated changes that would be missed by individual metabolite analysis [2].

Table 1: Comparison of the Three Primary MSEA Methods

| Method | Input Requirements | Key Feature | Primary Statistical Test | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overrepresentation Analysis (ORA) | List of compound names [2] | Tests for overrepresentation of a metabolite set in a given list [21] | Hypergeometric test [21] | Quick, initial screening of pre-selected metabolites |

| Single Sample Profiling (SSP) | Compound names and concentrations from a single sample [2] | Compares sample concentrations to reference ranges for metabolite sets [2] | Deviation scoring against reference database [2] | Personalized profiling, such as in clinical diagnostics |

| Quantitative Enrichment Analysis (QEA) | Compound names and concentrations from multiple samples [2] | Analyzes the entire ranked list of metabolites without arbitrary thresholds [2] | Rank-based enrichment score with permutation testing [2] | Comprehensive study analysis for detecting subtle, coordinated changes |

Core Components for MSEA Implementation

Successful implementation of MSEA depends on two foundational elements: well-annotated metabolite set libraries and a robust metabolite dictionary that facilitates name conversion.

Metabolite Set Libraries

The biological knowledge powering MSEA is encapsulated in libraries of predefined metabolite sets. These are curated groups of metabolites that share a common biological attribute. The creation of these libraries involves extensive manual curation and text-mining of scientific literature, textbooks, and public databases [2]. A typical comprehensive library, such as the one underpinning the web-based MSEA tool, contains approximately 1,000 sets organized into three main categories [2]:

- Pathway-associated Sets: These sets comprise metabolites involved in the same metabolic pathway (e.g., TCA cycle, glycolysis). The initial MSEA library included 84 such sets based on human pathways from the Small Molecular Pathway Database (SMPDB) [2]. Modern platforms like MetaboAnalyst have vastly expanded this, supporting pathway analysis for over 120 species [3].

- Disease-associated Sets: These sets include metabolites known to show significant concentration changes under specific pathological conditions. These are often subdivided based on the biofluid in which the changes are observed (e.g., blood, urine, cerebral-spinal fluid). The original MSEA resource contained 851 such disease-associated sets [2].

- Location-based Sets: These sets group metabolites based on their presence in specific locations, such as particular organs, tissues, or cellular organelles. The initial library contained 57 location-based sets derived from tissue and cellular location data in the HMDB [2].

For non-mammalian or highly specialized studies, MSEA also supports the use of custom, user-defined metabolite sets, allowing for flexible application across diverse research domains [2].

Metabolite Dictionary and Identifier Conversion

A critical technical challenge in metabolomics is the inconsistent use of metabolite names and identifiers across different analytical platforms and databases. To address this, MSEA tools incorporate a comprehensive metabolite dictionary that enables automatic conversion between common names, synonyms, and identifiers from major metabolomic databases [2]. This "normalization" process ensures that user-inputted metabolites are correctly mapped to the entries in the metabolite set libraries. Supported identifiers typically include those from HMDB, PubChem, ChEBI, KEGG, BiGG, METLIN, BioCyc, Reactome, and Wikipedia, among others [2].

Table 2: Key Metabolite Set Libraries and Their Composition in MSEA

| Library Category | Sub-category | Number of Sets | Data Sources | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway-associated | Human Metabolic Pathways | 84 (initial library) [2] | SMPDB [2] | Identifying disrupted energy metabolism in a disease model |

| Disease-associated | Blood | 398 (initial library) [2] | HMDB, MIC, PubMed [2] | Discovering plasma biomarker panels for disease diagnosis |