Metabolite-Metabolite Interaction Networks: From Construction to Application in Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of metabolite-metabolite interaction network analysis, a pivotal approach in systems biology for understanding complex metabolic processes.

Metabolite-Metabolite Interaction Networks: From Construction to Application in Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of metabolite-metabolite interaction network analysis, a pivotal approach in systems biology for understanding complex metabolic processes. It covers foundational concepts of metabolic networks as essential representations of biological systems where nodes represent metabolites and edges represent their interactions. The content explores diverse methodological approaches for network construction, including correlation-based, causal inference-based, and biochemical pathway-based models. It addresses critical troubleshooting aspects and optimization strategies for handling computational and analytical challenges. Furthermore, the article examines validation techniques and comparative analysis frameworks that enhance network reliability and biological interpretation. Targeted at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource demonstrates how metabolic network analysis facilitates biomarker discovery, reveals disease mechanisms, predicts drug metabolism, and enables the development of personalized treatment strategies.

Understanding Metabolic Networks: Core Concepts and Biological Significance

In the field of systems biology, a metabolic connectome is a graphical representation of the complex interactions within a metabolic system. It conceptualizes biological entities as nodes (e.g., metabolites, proteins, genes) and the physical, biochemical, or functional interactions between them as edges [1]. Metabolic networks are particularly significant because metabolites exhibit a closer relationship to an organism's phenotype compared to genes or proteins, and the metabolome can amplify small changes from the transcriptomic and proteomic levels [1]. The analysis of these networks relies on network theory and a suite of evaluation indicators to quantify characteristics and behaviors, providing profound insights into the fundamental patterns of biological systems [1].

Core Components of a Metabolic Connectome

Nodes: The Fundamental Entities

In a metabolic connectome, nodes represent the distinct biological entities involved in metabolic processes. Among these, metabolites are especially pivotal nodes because their levels provide a direct reflection of the organism's current physiological and phenotypic state [1]. The significance of metabolites as nodes is underscored by their ability to amplify even minor proteomic and transcriptomic changes [1]. In broader interaction networks, nodes can also encompass other molecular actors such as proteins, genes, and miRNAs, as demonstrated in studies of diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) [2].

Edges: Defining the Interactions

Edges represent the relationships or interactions between nodes. The nature of these edges can be defined by different types of relationships, which dictate the construction method and interpretation of the network [1].

- Statistical Correlations: Represented by correlation coefficients (e.g., Pearson, Spearman), these edges indicate coordinated behavior between the concentrations or levels of metabolites [1].

- Causal Relationships: Inferred through statistical models, these edges aim to describe directed, causal influences between entities, moving beyond mere correlation [1].

- Biochemical Reactions: These edges represent direct enzymatic conversions between metabolites, forming the basis of classical metabolic pathway maps [1].

- Chemical Structural Similarities: Edges can also be drawn based on the structural resemblance between metabolite molecules, suggesting potential functional similarities or relationships [1].

Network Topology: Describing the System's Structure

Network topology refers to the overall architecture and connectivity patterns of the network. It is quantified using specific metrics from graph theory, which allow researchers to move from a simple visual representation to a quantifiable model [1]. The key topological properties and metrics are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Topological Metrics for Metabolic Connectome Analysis

| Metric | Description | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Node Degree | The number of connections a node has to other nodes. | Identifies highly connected metabolites, potentially indicating hubs critical for network integrity and function [1]. |

| Clustering Coefficient | Measures the degree to which a node's neighbors are also connected to each other. | Reveals the tendency for formation of tightly interconnected modules or clusters, which may correspond to functional metabolic units [1]. |

| Average Shortest Path Length | The average number of steps along the shortest paths for all possible pairs of nodes. | Reflects the global efficiency of information or mass transfer across the network [1]. |

| Centrality | A family of metrics (e.g., betweenness centrality) that quantify a node's importance in facilitating communication or flow. | Pinpoints nodes that act as critical bridges between different parts of the network [1]. |

| Modularity | Measures the extent to which a network can be subdivided into distinct, non-overlapping communities. | Helps decompose the complex network into functionally coherent subsystems [1]. |

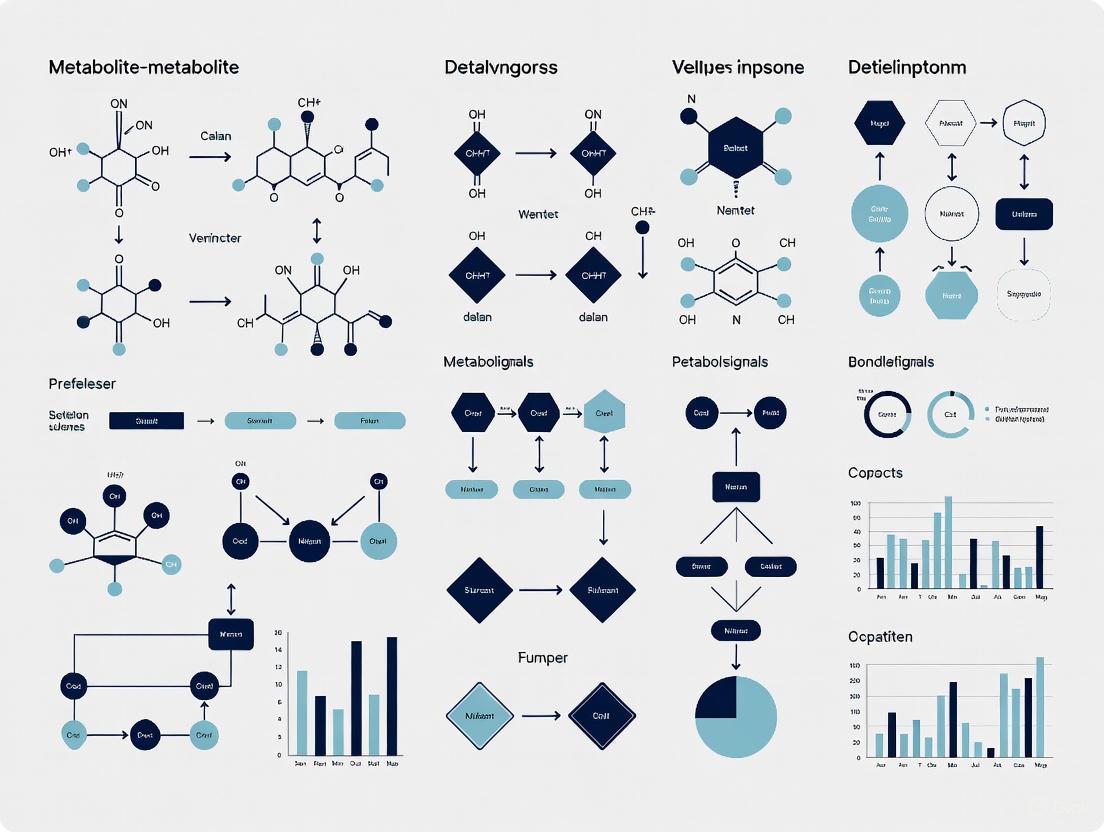

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for constructing and analyzing a metabolic connectome, from raw data to topological insight.

Diagram 1: Workflow for metabolic connectome construction and analysis.

Methods for Constructing Metabolic Networks

The construction of a metabolic connectome is a critical step that determines the type of biological questions that can be addressed. The choice of method depends on the available data and the research objectives.

Correlation-Based Network Construction

This is a widely used approach that establishes edges based on statistical correlations between the abundance levels of metabolites across multiple samples [1]. The process involves calculating a correlation matrix and applying a threshold to determine significant connections.

Table 2: Methods for Correlation-Based Network Construction

| Method | Relationship Type | Key Feature | Language/Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson Correlation | Linear | Measures linear dependence. Sensitive to outliers. | Python [1] |

| Spearman Rank Correlation | Monotonic | Measures monotonic (non-linear) dependence using rank order. | Python [1] |

| Distance Correlation | Monotonic/Non-linear | Measures linear and non-linear dependence; value of 0 implies independence. | Python [1] |

| Gaussian Graphical Model (GGM) | Conditional Dependency | Calculates partial correlations, filtering out indirect effects to reveal more direct relationships [1]. | R [1] |

The general workflow can be summarized as: 1) Input a data matrix of metabolite concentrations; 2) Compute a correlation matrix (e.g., Pearson, Spearman, or partial correlation); 3) Apply a significance threshold to the correlation values to create an adjacency matrix; 4) Construct the network graph from the adjacency matrix.

Causal-Based Network Construction

Causal networks aim to move beyond association to infer directed, causal influences between variables, providing a powerful framework for understanding the mechanistic underpinnings of metabolic regulation [1].

- Causal Inference Models: These are statistical frameworks for inferring causal relationships from observational data. They include latent causal models and causal graphical models, which use directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) to represent causal pathways [1].

- Structural Equation Modeling (SEM): A multivariate statistical model that tests hypothesized causal relationships by modeling the connections between observed and latent variables. It is described by the equation ( y = \lambda x + \beta y + \varepsilon ), where ( \lambda ) is the factor loading and ( \beta ) is the structural coefficient [1].

- Dynamic Causal Modeling (DCM): A method used for time-series data to model the temporal and causal influences between variables. It is based on dynamic system theory and can be expressed as ( zt = f(z, \theta) + \omega ), where ( zt ) is the metabolite concentration at time ( t ), and ( \theta ) represents the model parameters defining causal relationships and time delays [1].

Other Construction Methodologies

- Pathway-Based Networks: Constructs networks based on known biochemical reactions from established databases (e.g., KEGG, Reactome), representing the canonical metabolic pathways [1].

- Chemical Structure Similarity-Based Networks: Connects metabolites based on the similarity of their chemical structures, which can imply functional relatedness or shared biochemical roles [1].

Advanced Applications and Experimental Protocols

Metabolic connectomics has moved beyond cellular-level analysis to provide insights into organ-level communication and complex disease mechanisms.

The Whole-Body Metabolic Organ Connectome

A novel application involves using whole-body FDG-PET scans to construct partial correlation networks (PCNs) that reflect direct metabolic connectivity between different organs [3]. This approach provides a systems-level biomarker of metabolic homeostasis.

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Acquisition: Perform whole-body 2-[18F]FDG-PET scans on participants.

- Region of Interest (ROI) Definition: Segment the PET images to define ROIs for major organs (e.g., brain, heart, liver, skeletal muscle, adipose tissue).

- Metabolic Activity Quantification: Extract the standardized uptake value (SUV) or similar metric for each organ ROI.

- Network Construction: Compute a partial correlation network between the metabolic activities of all organ pairs. This controls for the global metabolic state, revealing direct connections.

- Network Analysis: Calculate global network metrics such as density (proportion of actual connections to possible connections) and disorder (a measure of network randomness). These metrics have been linked to allostatic load, with lower density and higher disorder associated with conditions like obesity, inflammation, and cancer [3].

Integrative Multi-Omics Network Analysis

Complex diseases often involve dysregulation across multiple biological layers. Integrative network analysis combines data from metabolomics, proteomics, and transcriptomics to build a more comprehensive model [2].

Case Study: Diabetic Cardiomyopathy (DCM) [2] Experimental Protocol:

- Component Identification: Select significant miRNAs, proteins, and metabolites associated with DCM pathogenesis through omics studies.

- Bipartite Network Construction:

- Manually construct an miRNA–protein interaction network using evidence from validated target databases (e.g., TarBase) and prediction algorithms.

- Construct protein–protein and protein–metabolite interaction networks using high-confidence interaction data (confidence score ≥ 0.7).

- Integrated Network Fusion: Merge the bipartite networks to form a unified miRNA–protein–metabolite interaction network.

- Key Player Identification: Use topological analysis (e.g., degree, betweenness centrality) to identify key regulatory nodes within the integrated network. In DCM, proposed key players included hsa-mir-122-5p, IL6, ACADM, bilirubin, and butyric acid, which are potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets [2].

The following diagram visualizes this multi-layered integrative approach.

Diagram 2: Multi-omics network integration for complex disease analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Metabolic Connectome Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Whole-Body FDG-PET Scanner | Enables quantification of glucose metabolism in multiple organs simultaneously for constructing the metabolic organ connectome [3]. |

| 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) | Radiolabeled glucose analog used as a tracer in PET imaging to measure metabolic activity in tissues [4] [3]. |

| Validated Interaction Databases (TarBase, STRING) | Provide high-confidence, experimentally validated data for constructing miRNA-protein and protein-protein interaction networks, respectively [2]. |

| Statistical Software (R, Python) | Platforms for implementing network construction algorithms (e.g., Gaussian Graphical Models in R, correlation analysis in Python) and calculating topological metrics [1]. |

| Pathway Databases (KEGG, Reactome) | Sources of canonical biochemical reaction data for building and validating pathway-based metabolic networks [1]. |

| Cytoscape | Open-source software platform for visualizing, analyzing, and modeling complex interaction networks [5]. |

| Antitubercular agent-18 | Antitubercular agent-18|InhA Inhibitor|RUO |

| Bace1-IN-10 | Bace1-IN-10, MF:C33H49N5O8S, MW:675.8 g/mol |

Metabolites, the small molecule end products of cellular regulatory and metabolic processes, play a dynamically influential role in shaping cellular phenotypes that extends far beyond their traditional view as passive intermediates. Within the context of metabolite-metabolite interaction networks, these molecules function as crucial information hubs that capture and amplify cellular states through their collective behaviors and regulatory capacities. The biological rationale for how metabolites amplify cellular phenotypes lies in their unique position at the functional terminus of the biological central dogma, their rapid response kinetics, and their multifaceted roles as regulatory effectors within complex biochemical networks [6]. Unlike other omics layers, metabolomics provides a direct functional readout of cellular activity, where subtle changes at the genomic, transcriptomic, or proteomic level become amplified into measurable metabolic rearrangements [7]. This amplification occurs through several interconnected biological mechanisms that operate across different scales of cellular organization, from allosteric regulation of single enzymes to system-wide flux redistributions across metabolic networks [8] [6].

Key Biological Mechanisms of Phenotypic Amplification

Metabolites as Information Integrators and Signal Transducers

Metabolites serve as highly sensitive integrators of cellular information by responding rapidly to genetic, environmental, and regulatory perturbations. This integrative capacity enables them to amplify subtle phenotypic changes through several key mechanisms:

Allosteric Regulation: Metabolites directly modulate enzyme activity and flux through metabolic pathways by binding to regulatory sites, creating amplification cascades where a small change in metabolite concentration produces disproportionately large effects on pathway output [8]. The regulatory strength (RS) of such effectors can be quantitated, representing the strength of up- or down-regulation of a reaction step compared to its non-inhibited or non-activated state [8].

Network-Wide Propagation: Localized metabolic changes propagate through highly connected metabolic networks, where the interconnection of pathways ensures that perturbations are not isolated but rather amplified across multiple biochemical processes [6]. This network property explains how single metabolite alterations can influence seemingly unrelated pathways and cellular functions.

Mass Action Kinetics: As substrates and products in biochemical reactions, metabolites directly influence reaction rates and thermodynamic equilibria through law of mass action effects, creating self-amplifying or dampening cycles that magnify initial perturbations [9].

Regulatory Strength and Its Quantitative Assessment

The concept of Regulatory Strength (RS) provides a quantitative framework for understanding how metabolites amplify phenotypic states through enzyme regulation [8]. This measure defines the strength of regulatory interactions between metabolite pools and reaction steps with specific properties:

Table 1: Properties of Regulatory Strength (RS) Metric

| Property | Description | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Applicability | Defined for all effectors (inhibitors/activators) not part of substrate/product sets | Covers comprehensive regulatory interactions beyond core reactants |

| Quantification | Single numerical value associated with each effector edge in network | Enables quantitative comparison and visualization of regulatory influences |

| Dynamic Nature | Calculated from momentary pool sizes, fluxes, kinetic parameters | Captures time-dependent regulatory changes in response to perturbations |

| Interpretation Scale | Percentage scale (0%-100%) where 100% = maximal possible inhibition/activation | Intuitive interpretation of regulatory impact strength |

| Multi-effector Context | Percentages indicate proportional contribution of different effectors to total regulation | Reveals combinatorial control mechanisms in complex regulatory schemes |

The RS value is calculated from current metabolite concentrations, flux states, and kinetic parameters of the relevant enzymes, providing a time-dependent quantity that reflects the immediate regulatory state of the system without dependence on historical states [8]. This quantitative approach reveals how metabolites collectively regulate metabolic fluxes, with the percentage values indicating the relative contribution of different effectors when multiple regulators influence a single reaction step.

Experimental Evidence and Case Studies

Dynamic Network Responses in E. coli

Studies visualizing regulatory interactions in dynamic E. coli networks have demonstrated how metabolite-mediated amplification functions in living systems. When subjected to environmental perturbations, specific metabolites emerge as key regulatory nodes that coordinate system-wide metabolic reprogramming [8]. For example:

Catabolite Repression Metabolites: Certain glycolytic intermediates amplify carbon source preference phenotypes through allosteric regulation of enzyme complexes, creating bistable metabolic states that propagate through interconnected pathways.

Energy Charge Metabolites: ATP, ADP, and AMP concentrations modulate numerous metabolic pathways simultaneously, amplifying energy status into coordinated regulation of ATP-producing and ATP-consuming processes across the entire metabolic network.

The visualization of regulatory strengths in these networks revealed that approximately 15-30% of measurable metabolites functioned as significant regulators under physiological conditions, with RS values ranging from 20-80% for the most influential effectors [8].

Network Analysis in Untargeted Metabolomics

Advanced network analysis approaches in untargeted metabolomics have provided systematic evidence for the amplification of cellular phenotypes through metabolite interactions. By constructing both knowledge networks (based on known biochemical reactions) and experimental networks (derived from correlation patterns, spectral similarities, and co-regulation) [6], researchers can observe how perturbations become amplified:

Table 2: Network Types for Analyzing Metabolite Amplification

| Network Type | Basis of Construction | Revealed Amplification Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Correlation Networks | Statistical relationships between metabolite abundances | Identifies co-regulated metabolite modules that respond coordinately to perturbations |

| Biochemical Reaction Networks | Known substrate-product relationships from databases | Maps perturbation propagation through established metabolic pathways |

| Spectral Similarity Networks | MS/MS spectral similarities between features | Reveals structural relationships and coordinated changes in metabolite families |

| Multi-omics Integration Networks | Combined metabolomic, genomic, and proteomic data | Identifies points where genetic variants become amplified through metabolic rearrangements |

Studies applying these approaches have demonstrated that metabolite clusters identified through network analysis often explain phenotypic variation more effectively than individual metabolites, highlighting the amplification that occurs through coordinated changes across metabolite groups [6]. For example, in cancer metabolomics, network analyses have revealed how oncogenic mutations become amplified through coordinated changes in central carbon metabolism, nucleotide synthesis, and phospholipid remodeling, creating distinct metabolic subphenotypes with clinical implications.

Methodologies for Investigating Metabolic Amplification

Analytical Workflows for Network Construction

Comprehensive investigation of metabolite-mediated phenotypic amplification requires integrated analytical workflows that combine multiple experimental and computational approaches:

Quantitative Visualization of Regulatory Interactions

The Regulatory Strength (RS) visualization approach enables direct observation of how metabolites influence reaction steps in metabolic networks [8]. This methodology includes:

RS Calculation: Computational determination of regulatory effects based on current metabolite concentrations, enzyme kinetic parameters, and the specific kinetic formula for each reaction.

Network Mapping: Visualization of RS values directly on metabolic network diagrams, typically using edge coloring, thickness, or numerical annotations to represent the strength and direction (activation/inhibition) of regulatory interactions.

Dynamic Tracking: Monitoring changes in RS values over time or across different physiological conditions to identify key regulatory metabolites that drive phenotypic transitions.

This approach has been successfully implemented in tools like PathCaseMAW, which provides steady-state metabolic network dynamics analysis and visualization capabilities for investigating how metabolites regulate metabolic fluxes [9].

Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Amplification Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolite Amplification Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | Methanol, Acetonitrile, Water | Sample preparation and chromatographic separation for reproducible metabolomics |

| Stable Isotope Tracers | ^13^C-Glucose, ^15^N-Glutamine, ^2^H2O | Metabolic flux analysis to quantify pathway activities and network propagation |

| Chemical Standards | Certified reference metabolites | Compound identification and quantification in targeted and untargeted analyses |

| Enzyme Inhibitors/Activators | Specific allosteric modulators | Experimental manipulation of regulatory nodes to test amplification mechanisms |

| Sample Collection Reagents | Cold methanol, acetonitrile, quenching solutions | Immediate metabolic arrest to preserve in vivo metabolic states |

| Derivatization Reagents | MSTFA, MOX, BSTFA | Chemical modification for enhanced detection of specific metabolite classes |

| Quality Control Materials | Pooled quality control samples, NIST SRM 1950 | Monitoring analytical performance and cross-study data comparability |

Understanding the fundamental biological rationale of how metabolites amplify cellular phenotypes provides powerful insights for both basic research and therapeutic development. For researchers investigating complex diseases, this perspective emphasizes the importance of moving beyond single metabolite biomarkers to network-level analyses that capture the amplified phenotypic signatures [6] [7]. In drug development, targeting the key regulatory metabolites or their downstream effects offers promising strategies for modulating pathological phenotypes with potentially greater efficacy than single-target approaches. The integration of quantitative regulatory strength measurements with comprehensive network analyses represents a cutting-edge approach for deciphering how genetic, environmental, and therapeutic interventions become amplified into observable phenotypic outcomes through metabolic networks [8] [9] [6]. As these methodologies continue to advance, they will increasingly enable researchers to not only observe but also predict and manipulate the amplification of cellular phenotypes through targeted metabolic interventions.

Network analysis provides a powerful framework for representing and analyzing complex biological systems, where individual components are represented as nodes (or vertices) and their interactions as edges (or links). In the specific context of metabolite-metabolite interaction network analysis, each metabolite constitutes a node, while edges represent biochemical transformations or significant statistical relationships between them. This approach enables researchers to move beyond studying isolated components to understanding the system-level properties that emerge from their interactions. The structural properties of these networks—including degree distribution, various centrality measures, and small-world characteristics—provide crucial insights into metabolic organization, robustness, and functional capabilities [10] [11].

The application of network theory to biological systems has revealed fundamental design principles underlying metabolic organization across diverse organisms. By quantifying connectivity patterns between nodes, researchers can identify strategically important metabolites that may play disproportionate roles in network functionality and stability. These analyses have demonstrated that biological networks often exhibit non-random topological features that reflect their evolutionary history and functional constraints. For metabolite-metabolite interaction networks specifically, understanding these properties enables researchers to predict metabolic fluxes, identify potential drug targets, and understand how perturbations propagate through metabolic systems [11].

Core Network Properties and Their Biological Significance

Degree and Degree Distribution

The degree of a node represents the number of direct connections it has to other nodes in the network. In a metabolite-metabolite interaction network, a metabolite's degree corresponds to the number of other metabolites with which it directly interacts through biochemical reactions. Degree is a local centrality measure that provides immediate information about a node's local connectivity. Analysis of degree distributions across networks has revealed that biological networks frequently exhibit power-law distributions, where most nodes have few connections, while a few nodes (hubs) have exceptionally high connectivity [11].

The table below summarizes key degree-related metrics and their biological interpretations in metabolite-metabolite interaction networks:

Table 1: Degree-Based Metrics in Metabolic Networks

| Metric | Mathematical Definition | Biological Interpretation | Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree (k) | Number of edges incident to a node | Number of direct biochemical interaction partners of a metabolite | Count of adjacent edges for each node |

| Average Degree | ⟨k⟩ = (2 × Number of edges) / Number of nodes | Overall network connectivity | Sum of all node degrees divided by number of nodes |

| Degree Distribution P(k) | Probability that a randomly selected node has degree k | Heterogeneity of metabolite participation in reactions | Frequency distribution of node degrees |

| Hub Metabolites | Nodes with k ≫ ⟨k⟩ | Metabolites participating in numerous biochemical pathways (e.g., ATP, NADH, acetyl-CoA) | Identify nodes in top percentile of degree distribution |

In scale-free networks, which characterize many biological systems, the degree distribution follows a power law: P(k) ~ k^(-γ). This topological feature has significant implications for network robustness, as the removal of random nodes rarely disrupts network connectivity, while targeted removal of hubs can fragment the network. This property relates directly to the centrality-lethality rule observed in biological networks, where highly connected nodes tend to be more essential for survival [11].

Centrality Measures

Centrality measures quantify the importance or influence of nodes within a network, with different metrics capturing distinct aspects of topological significance. These measures help identify strategic metabolites that may play critical roles in metabolic control and regulation beyond what simple degree analysis can reveal [11].

Table 2: Centrality Measures in Metabolic Networks

| Centrality Measure | Definition | Biological Relevance | Interpretation in Metabolic Networks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree Centrality | Number of direct connections | Local connectivity importance | Metabolites that participate in many different reactions |

| Betweenness Centrality | Fraction of shortest paths passing through a node | Control over information flow in the network | Metabolites that act as bridges between different metabolic modules |

| Closeness Centrality | Reciprocal of the sum of shortest path distances to all other nodes | Efficiency in reaching other nodes | Metabolites that can quickly interact with many others in the network |

| Eigenvector Centrality | Influence of a node based on its connections' importance | Connection to influential neighbors | Metabolites connected to other highly connected and central metabolites |

| Subgraph Centrality | Number of closed walks starting and ending at the node, weighted by length | Participation in network feedback loops | Metabolites involved in cyclic metabolic pathways and regulatory loops |

The robustness of these centrality measures varies significantly under different sampling conditions. Local measures like degree centrality generally show greater robustness to incomplete network data, while global measures such as betweenness and closeness centrality are more sensitive to missing interactions. This has important implications for interpreting centrality analyses in metabolite-metabolite interaction networks, which are often incomplete due to technical limitations in detecting all metabolic interactions [11].

Figure 1: Centrality measures and their biological interpretations in metabolic networks, showing how different metrics highlight distinct aspects of metabolic importance.

Small-World Characteristics

Small-world networks represent an important topological class that combines high local clustering with short path lengths between nodes. This organization has significant functional implications for biological systems, as it supports both functional specialization (through clustering) and efficient communication (through short paths) [11].

The small-world property is quantified using two key metrics: the clustering coefficient and average path length. The clustering coefficient measures the degree to which nodes tend to cluster together, calculated as the probability that two neighbors of a node are also connected to each other. The average path length represents the mean shortest distance between all pairs of nodes in the network. Small-world networks are characterized by a high clustering coefficient relative to random networks and a similar average path length to random networks.

Table 3: Small-World Metrics in Metabolic Networks

| Metric | Definition | Calculation | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clustering Coefficient | Measure of local connectivity density | C = 3 × Number of triangles / Number of connected triples | Functional modularity and metabolic channeling |

| Average Path Length | Mean shortest distance between node pairs | L = (1/(n(n-1))) × Σd(i,j) | Efficiency of metabolic communication and regulation |

| Small-World Coefficient | Ratio of normalized clustering to normalized path length | σ = (C/Crandom)/(L/Lrandom) | Quantification of small-world topology (σ > 1 indicates small-world) |

In metabolic networks, small-world organization supports the balance between local specialization within metabolic pathways and global integration across different pathways. This architecture enables efficient routing of metabolic intermediates while maintaining functional modules dedicated to specific biochemical processes. The high clustering observed in metabolic networks often corresponds to known biochemical pathways, where metabolites within the same pathway are highly interconnected [11].

Methodological Framework for Analyzing Metabolic Networks

Network Construction from Metabolic Data

The construction of metabolite-metabolite interaction networks begins with compiling comprehensive reaction data from biochemical databases such as BRENDA, MetaCyc, or KEGG. Two primary approaches are used: substrate-product networks (where metabolites are connected if they participate in the same reaction as substrate and product) and correlation-based networks (where connections represent significant statistical associations between metabolite concentrations) [10] [12].

The experimental workflow for constructing and analyzing these networks involves multiple stages with specific methodological considerations at each step:

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for constructing and analyzing metabolite-metabolite interaction networks, showing key stages from data collection to biological validation.

Addressing Sampling Bias in Network Analysis

A critical methodological consideration in analyzing biological networks is sampling bias, which arises from incomplete detection of all true interactions in a system. This bias can significantly impact calculated network properties, particularly centrality measures. Recent research has systematically evaluated how different types of sampling biases affect network metrics through simulation studies [11].

The table below summarizes common sampling biases and their effects on network properties:

Table 4: Sampling Biases and Their Impact on Network Properties

| Bias Type | Description | Effect on Degree Distribution | Effect on Centrality Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Edge Removal | Non-selective omission of edges | Generally preserves distribution shape | Global measures most affected |

| Highly Connected Edge Removal | Preferential loss of edges involving highly connected nodes | Flattens degree distribution | Degree centrality most affected |

| Low Connected Edge Removal | Preferential loss of edges involving poorly connected nodes | Exaggerates hub dominance | Betweenness centrality most affected |

| Random Walk Edge Removal | Removal proportional to edge traversal probability | Distorts local clustering | Closeness centrality most affected |

Studies have shown that protein interaction networks demonstrate the highest robustness to sampling bias, followed by metabolite, gene regulatory, and reaction networks. Local centrality measures like degree centrality generally show greater robustness to incomplete network data compared to global measures such as betweenness and closeness centrality. These findings highlight the importance of considering network completeness when interpreting topological analyses and comparing results across different studies [11].

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol for Metabolic Network Construction and Analysis

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for constructing metabolite-metabolite interaction networks from biochemical data and analyzing their key topological properties.

Materials and Reagents:

- Biochemical database access (KEGG, BRENDA, MetaCyc)

- Statistical software (R, Python with NetworkX/pandas)

- Network analysis tools (Cytoscape, Gephi)

- High-performance computing resources (for large networks)

Procedure:

Data Acquisition and Curation

- Download comprehensive reaction data for target organism from KEGG database using KEGG REST API or flat file downloads

- Extract metabolite-reaction associations, recording substrates, products, and enzymes

- Resolve metabolite naming inconsistencies using chemical identifier services (PubChem, ChEBI)

- Filter reactions to include only those with biochemical evidence

Network Construction

- Create node list comprising all unique metabolites

- Construct edge list where two metabolites are connected if they participate in the same reaction as substrate and product

- Apply stoichiometric constraints to distinguish directionality where appropriate

- Generate adjacency matrix representation of the network

Topological Analysis

- Calculate degree distribution using NetworkX degree() function in Python

- Compute centrality measures:

- Degree centrality:

nx.degree_centrality(G) - Betweenness centrality:

nx.betweenness_centrality(G) - Closeness centrality:

nx.closeness_centrality(G) - Eigenvector centrality:

nx.eigenvector_centrality(G)

- Degree centrality:

- Assess small-world properties:

- Calculate clustering coefficient:

nx.average_clustering(G) - Compute average shortest path length:

nx.average_shortest_path_length(G) - Generate appropriate random networks (Erdős-Rényi or degree-preserving) for comparison

- Calculate small-world coefficient σ

- Calculate clustering coefficient:

Validation and Interpretation

- Perform robustness tests by systematically removing edges and recalculating metrics

- Compare identified hub metabolites with known essential metabolites from literature

- Conduct enrichment analysis of highly central metabolites in biochemical pathways

- Validate network connectivity against known metabolic pathways

Troubleshooting:

- If network is too fragmented, check for missing reactions or connectivity constraints

- If centrality measures show unexpected values, verify network connectivity and edge weights

- For computational limitations with large networks, use approximation algorithms for betweenness calculation

Research Reagent Solutions for Network Analysis

Table 5: Essential Research Tools for Metabolic Network Analysis

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biochemical Databases | KEGG, BRENDA, MetaCyc, BioGRID | Source of curated metabolic reaction data | Network construction and validation |

| Network Analysis Software | NetworkX (Python), igraph (R), Cytoscape | Calculation of network properties and visualization | Topological analysis and graphical representation |

| Statistical Computing Environments | R, Python with pandas/NumPy/SciPy | Data preprocessing, statistical analysis, and custom algorithm implementation | Data manipulation and computational analysis |

| Specialized Metabolic Modeling Tools | CIRI, SR-FBA, SCOUR, SIMMER | Prediction of metabolite-protein interactions and integration with metabolic models | Constraint-based modeling and interaction prediction [12] |

| Data Visualization Platforms | Gephi, Cytoscape, Graphviz | Visualization of complex networks and creation of publication-quality figures | Network visualization and graphical abstract creation |

Applications in Metabolite-Metabolite Interaction Research

The analysis of key network properties in metabolite-metabolite interaction networks has enabled significant advances in understanding metabolic regulation and identifying potential therapeutic targets. Recent research has demonstrated the value of this approach in studying complex diseases such as diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM), where integrative network analysis identified specific metabolites including bilirubin, butyric acid, octanoylcarnitine, isoleucine, leucine, alanine, glutamine, and L-valine as key players in disease pathogenesis [10].

These network-based approaches have revealed that metabolic diseases often involve disturbed interaction patterns rather than simply altered concentrations of individual metabolites. By identifying metabolites with high betweenness centrality—which act as critical bridges between different metabolic modules—researchers can pinpoint potential intervention points that might influence multiple pathways simultaneously. This systems-level understanding moves beyond the traditional one-metabolite-one-effect paradigm to capture the emergent complexity of metabolic regulation [10] [5].

Advanced computational approaches now integrate metabolite-metabolite interaction networks with other biological networks, including protein-protein interactions and gene regulatory networks. This multi-layer network analysis provides a more comprehensive view of cellular regulation and has been particularly valuable in understanding the mechanisms of metabolic medications such as GLP-1 receptor agonists, which appear to exert their beneficial effects through coordinated modulation of multiple interacting metabolic pathways [5].

The continuing development of constraint-based modeling approaches like CIRI (Competitive Inhibitory Regulatory Interaction) and SR-FBA (Steady-State Regulatory Flux Balance Analysis) has enhanced our ability to predict how perturbations to specific metabolites propagate through metabolic networks, further strengthening the translational potential of network-based analyses in drug discovery and therapeutic development [12].

Metabolic Networks as Representations of Biochemical Reality

Metabolic networks are comprehensive representations of the biochemical reactions and interactions that define cellular physiology. These networks systematically map the relationships between metabolites, enzymes, and genes, providing a framework for understanding how organisms convert nutrients into energy and cellular components. The construction and analysis of these networks have been revolutionized by omics technologies and bioinformatics tools, enabling researchers to move from studying individual pathways to investigating system-wide metabolic interactions [13] [14]. This shift has profound implications for drug development, as metabolic dysregulation is a hallmark of numerous diseases including cancer, diabetes, and neurodegenerative disorders [13].

Within the context of metabolite-metabolite interaction network research, metabolic networks serve as computational scaffolds for integrating experimental data, identifying regulatory nodes, and predicting system behavior under various genetic and environmental conditions. The field continues to evolve with advances in analytical techniques, computational modeling, and multi-omics integration, offering increasingly sophisticated approaches to deciphering biochemical reality [15] [16].

Theoretical Foundations of Metabolic Networks

Basic Components and Structure

Metabolic networks consist of several interconnected elements that form a complex biochemical system:

- Metabolites: Small molecules that serve as substrates, intermediates, and products of metabolic reactions. These include amino acids, sugars, fatty acids, lipids, and organic acids [13].

- Reactions: Biochemical transformations that convert metabolites into other metabolites, often catalyzed by enzymes.

- Enzymes: Protein catalysts that facilitate metabolic reactions, frequently encoded by genes that can be regulated in response to cellular conditions.

- Pathways: Series of connected reactions that perform specific metabolic functions, such as glycolysis, TCA cycle, or fatty acid biosynthesis.

The network structure emerges from the connectivity between these components, forming a directed graph where metabolites are connected through reactions [14]. This representation captures the complexity of metabolism, where pathways are highly interconnected rather than operating as independent entities [14].

Different computational representations of metabolic networks serve distinct analytical purposes:

Table 1: Metabolic Network Representation Models

| Model Type | Basic Components | Connectivity Rules | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Graph | Nodes: Reactions; Edges: Shared metabolites | Directed edges represent metabolite flow between reactions | Pathway analysis; Metabolic reconstruction [15] |

| Metabolic DAG (m-DAG) | Nodes: Metabolic Building Blocks (MBBs); Edges: Connectivity between MBBs | Directed edges connect MBBs based on reaction graph connectivity | Network topology analysis; Large-scale comparison [15] |

| Two-Level Representation | Level 1: Pathways as nodes; Level 2: Reactions within pathways | Edges between pathways based on shared non-ubiquitous compounds | Functional and structural comparison between organisms [14] |

| Stoichiometric Matrix | Rows: Metabolites; Columns: Reactions | Matrix elements: Stoichiometric coefficients | Flux balance analysis; Constraint-based modeling [17] |

The m-DAG representation is particularly valuable for simplifying complex networks by collapsing strongly connected components (groups of reactions where each is reachable from any other) into single nodes called Metabolic Building Blocks (MBBs). This abstraction significantly reduces node count while preserving network connectivity, enabling more efficient computational analysis and visualization of large metabolic networks [15].

Metabolic Network Reconstruction Methodologies

Reconstruction of metabolic networks relies on curated biological databases that provide standardized metabolic information:

- KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes): Provides reference pathways, organism-specific metabolic maps, and associations between genes, enzymes, and reactions [15] [14].

- BioCyc/MetaCyc: Collection of pathway databases with curated metabolic information from multiple organisms [15].

- HMDB (Human Metabolome Database): Contains detailed information about human metabolites and their associations with diseases [18].

- STITCH: Database of known and predicted interactions between chemicals and proteins, including metabolic enzymes [18].

These databases provide the foundational data necessary for reconstructing organism-specific metabolic networks, though they often require integration and reconciliation due to differences in nomenclature and curation standards [14].

Reconstruction Workflows

The process of reconstructing metabolic networks typically follows a structured workflow:

Figure 1: Metabolic network reconstruction workflow. SCCs: Strongly Connected Components.

The reconstruction process begins with defining the scope (single organism, community, or specific pathways) and retrieving relevant data from curated databases. The initial reconstruction produces a reaction graph where nodes represent biochemical reactions and edges represent shared metabolites. This graph is then transformed into a metabolic Directed Acyclic Graph (m-DAG) by identifying and collapsing strongly connected components into metabolic building blocks (MBBs). The final steps involve validating the network completeness and performing functional annotation [15] [14].

Automated tools like MetaDAG and MetNet have streamlined this process, enabling reconstruction from various input types including organism identifiers, specific reactions, enzymes, or KEGG Orthology (KO) identifiers [15] [14].

Analysis Approaches for Metabolic Networks

Topological Analysis

Topological analysis examines the structural properties of metabolic networks without considering reaction kinetics. Key approaches include:

- Connectivity Analysis: Identifying highly connected metabolites (hubs) that may represent critical regulatory points in the network.

- Pathway Analysis: Determining the shortest metabolic paths between metabolites and identifying alternative routes.

- Module Detection: Decomposing the network into functional modules or subsystems that perform specific metabolic functions.

The m-DAG representation facilitates topological analysis by reducing network complexity while maintaining connectivity information, enabling researchers to identify key metabolic building blocks and their relationships [15].

Comparative Analysis

Comparative approaches analyze differences and similarities between metabolic networks of different organisms or conditions:

- Pan vs. Core Metabolism: The pan metabolism represents all metabolic capabilities across a group of organisms, while core metabolism refers to functions shared by all members [15].

- Similarity Measures: Quantitative indices that capture functional and structural similarities between networks at both pathway and reaction levels [14].

- Phylogenetic Profiling: Examining how metabolic capabilities correlate with evolutionary relationships.

Table 2: Computational Tools for Metabolic Network Analysis

| Tool | Primary Function | Input Types | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MetaDAG [15] | Metabolic network reconstruction & analysis | Organism IDs, Reactions, Enzymes, KOs | Generates reaction graphs and m-DAGs; Comparative analysis | Taxonomy classification; Diet response analysis |

| MetNet [14] | Reconstruction & comparison | KEGG organism IDs | Two-level representation; Similarity measures | Organism comparison; Evolutionary studies |

| MetaboAnalyst [18] | Network visualization & integration | Metabolite lists, Expression data | Multiple network types; Statistical analysis | Biomarker discovery; Multi-omics integration |

| AutoKEGGRec [14] | Automated reconstruction | KEGG organism IDs | Generates reaction-compound networks | Single organism metabolism analysis |

Dynamic and Kinetic Analysis

While structural analysis provides insights into metabolic capabilities, understanding network dynamics requires incorporating kinetic parameters:

- Kinetic Modules: Recently introduced concept identifying functional modules based on the coupling of reaction rates, linking network structure with dynamics [16].

- Power Law Formalism: Mathematical framework that represents reaction rates as power law functions of metabolite concentrations, characterized by kinetic parameters (magnitude of fluxes) and kinetic orders (regulatory structure) [17].

- Concentration Robustness: Analysis of how networks maintain stable metabolite concentrations despite environmental fluctuations, with breakdowns in robustness associated with disease states [16].

The emerging concept of kinetic modules represents a significant advance as it connects network structure with dynamics, helping explain how biochemical networks maintain functionality under varying conditions [16].

Experimental Protocols for Metabolic Network Construction and Validation

Multi-omics Integration Protocol

Integrating metabolomics with other omics data enhances metabolic network contextualization:

Sample Preparation:

- Collect biological samples (tissue, plasma, urine, or cell culture)

- Perform metabolite extraction using appropriate solvents (methanol, acetonitrile, or chloroform-methanol mixtures)

- Split samples for parallel metabolomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic analyses

Data Acquisition:

- Metabolomics: Apply LC-MS or GC-MS analysis with quality control samples [13]

- Transcriptomics: Perform RNA sequencing or microarray analysis

- Proteomics: Conduct shotgun proteomics or targeted protein quantification

Data Preprocessing:

- Metabolite Identification: Process raw MS data using XCMS, MAVEN, or MZmine3 [13]

- Quality Control: Remove metabolic features with high variance in QC samples [13]

- Normalization: Apply appropriate normalization to reduce technical variation [13]

- Annotation: Follow Metabolomics Standards Initiative (MSI) guidelines for reporting metabolite identification levels [13]

Network Integration:

- Map identified metabolites to KEGG or Recon networks

- Overlay transcriptomic and proteomic data to identify actively expressed pathways

- Construct condition-specific metabolic networks

Protein-Metabolite Interaction Mapping Protocol

Recent advances in protein-metabolite interaction (PMI) mapping provide experimental validation of metabolic network edges:

Sample Preparation:

- Cultivate cells (E. coli used in original study) under defined conditions [19]

- Prepare cell lysates while maintaining native protein-metabolite interactions

- Remove debris by centrifugation

Multi-dimensional Chromatography:

- Perform size exclusion chromatography to separate complexes by molecular weight

- Apply ion exchange chromatography to separate by charge characteristics

- Collect fractions across both separation dimensions [19]

Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- Analyze fractions using LC-MS/MS

- Identify proteins using database search algorithms

- Detect and quantify metabolites using targeted and untargeted approaches

Data Integration:

- Apply PROMIS algorithm to distinguish true interactions from coincidental co-elution [19]

- Construct PMI network using statistical confidence measures

- Validate interactions using known complexes from literature

- Integrate with metabolic networks to add regulatory constraints

This integrated chromatographic approach significantly enhances PMI mapping accuracy, resulting in high-confidence networks such as the 994 interactions involving 51 metabolites and 465 proteins reported in E. coli [19].

Applications in Disease Research and Drug Development

Metabolic Dysregulation in Disease

Metabolic network analysis has revealed consistent patterns of dysregulation across major diseases:

- Cancer: Multiple cancers show significant alterations in TCA cycle metabolites, methionine metabolism, fatty acid metabolism, and glycolysis [13].

- Diabetes: Disorders in acetoacetate metabolism, acylcarnitine metabolism, palmitic acid metabolism, and linolenic acid metabolism have been identified [13].

- Alzheimer's Disease: Abnormalities in amino acid metabolism, fatty acid metabolism, glycerophospholipid metabolism, and polyamine metabolism are commonly observed [13].

These disease-specific metabolic signatures provide opportunities for biomarker discovery and therapeutic targeting.

Network Medicine Applications

Metabolic network analysis supports multiple aspects of drug development:

- Target Identification: Central metabolites and reactions in disease-altered networks represent potential therapeutic targets.

- Drug Mechanism Elucidation: Mapping drug-induced metabolic changes onto networks helps uncover mechanisms of action.

- Personalized Medicine: Constructing patient-specific metabolic networks enables stratification based on metabolic subtypes.

- Toxicity Prediction: Identifying off-target metabolic effects early in drug development.

MetaboAnalyst provides specialized network types including metabolite-disease, gene-metabolite, and metabolite-gene-disease interaction networks to facilitate these applications [18].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Metabolic Network Research

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS Systems | Separation and quantification of metabolites | Untargeted and targeted metabolomics; Validation of metabolic interactions [13] |

| GC-MS Systems | Analysis of volatile metabolites or derivatized compounds | Detection of amino acids, organic acids, sugars, and other volatile compounds [13] |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Non-destructive structural elucidation of metabolites | Metabolic fingerprinting; Structural validation of unknown metabolites [13] |

| KEGG Database Access | Curated metabolic pathway information | Metabolic network reconstruction; Pathway mapping [15] [14] |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography Resins | Separation of protein-metabolite complexes by molecular size | Protein-metabolite interaction studies; Complex separation [19] |

| Ion Exchange Chromatography Resins | Separation by charge characteristics | Enhanced PMI mapping; Multi-dimensional chromatography [19] |

| QC Samples (Pooled) | Quality control for analytical variance assessment | Metabolomics data normalization; Technical variation correction [13] |

Metabolic networks provide powerful representations of biochemical reality that integrate structural, functional, and dynamic aspects of metabolism. The continuing development of computational tools like MetaDAG and MetNet has automated the reconstruction process, while analytical advances such as kinetic module analysis have bridged the gap between network structure and dynamics. Experimental methods for mapping protein-metabolite interactions provide empirical validation of network edges, enhancing their biological relevance.

For metabolite-metabolite interaction network research, these networks serve as essential scaffolds for data integration, hypothesis generation, and predictive modeling. As multi-omics technologies evolve and kinetic parameterization improves, metabolic networks will offer increasingly accurate representations of biochemical reality, accelerating discovery in basic research and drug development.

The integration of proteomics and transcriptomics represents a cornerstone of multi-omics research, providing a powerful framework for understanding the complex flow of genetic information from RNA transcription to protein translation. Within the context of metabolite-metabolite interaction network analysis, this integration enables researchers to bridge the gap between gene expression regulation and the enzymatic processes that ultimately shape the metabolome. While transcriptomics reveals which genes are being transcribed, proteomics offers a direct window into the functional output of cells and tissues, identifying the proteins that catalyze metabolic reactions and regulate metabolic pathways [20]. This layered approach is essential for distinguishing causal relationships from mere associations in biological systems, particularly in drug discovery and development where understanding the functional consequences of genetic variations is critical [20] [21]. The integration of these omics layers facilitates a more accurate mapping of biological pathways, guiding researchers in understanding the drivers of pathological states and identifying druggable targets [20].

Methodological Approaches for Integration

The integration of transcriptomic and proteomic data can be achieved through multiple computational strategies, each with distinct strengths and applications. These methods can be broadly categorized based on their underlying mathematical principles and the nature of the data they process.

Table 1: Computational Methods for Transcriptomics and Proteomics Integration

| Integration Approach | Key Principle | Representative Tools | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation-Based | Identifies statistical relationships (e.g., Pearson correlation) between mRNA levels and protein abundance [22]. | Custom scripts, Cytoscape [22] | Gene-protein network construction, identification of co-regulated modules. |

| Factor Analysis | Reduces data dimensionality by identifying latent factors that explain variance across both omics layers [23]. | MOFA+ [23] | Uncovering hidden biological drivers, subtype identification. |

| Network-Based | Uses graph structures to represent and integrate molecular entities and their relationships [22] [23]. | Weighted Nearest Neighbors (Seurat v4) [23] | Cell-type identification, multi-omics data visualization. |

| Machine Learning (Variational Autoencoders) | Learns a joint representation of different omics data in a lower-dimensional space [23]. | scMVAE, totalVI, Cobolt [23] | Data imputation, pattern recognition, prediction of clinical outcomes. |

Workflow for Multi-Omics Integration

A standardized workflow is crucial for robust integration of transcriptomic and proteomic data. The following diagram outlines the key stages from data generation to biological interpretation, with particular emphasis on the points of integration.

Correlation-Based Integration Strategies

Correlation-based methods serve as a foundational approach for integrating transcriptomic and proteomic data. These strategies involve applying statistical correlations, such as the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC), to identify mRNA-protein pairs that exhibit coordinated abundance patterns [22]. This approach can be extended to construct gene-protein networks where genes and proteins are represented as nodes, and edges represent the strength of their correlations [22]. Such networks help identify key regulatory nodes and pathways involved in metabolic processes. For enhanced insights, correlation analysis can be combined with co-expression analysis, where modules of co-expressed genes identified from transcriptomics data are linked to the abundance patterns of proteins, particularly enzymes, to identify metabolic pathways that are co-regulated with specific transcriptional programs [22].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Gene-Protein Network Construction

This protocol describes a correlation-based method to construct an integrative network from transcriptomic and proteomic data derived from the same biological samples.

- Data Collection and Preprocessing: Collect matched mRNA expression and protein abundance data from the same set of biological samples. Preprocess the raw data, which includes normalization, log-transformation, and quality control to remove technical artifacts [13].

- Data Integration via Correlation Analysis: For each gene-protein pair, calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) between the mRNA expression levels and the corresponding protein abundance across all samples [22].

- Statistical Filtering: Apply a significance threshold (e.g., p-value < 0.05) and a minimum correlation strength threshold (e.g., |PCC| > 0.6) to filter out spurious associations. Adjust for multiple testing using methods like Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) control.

- Network Construction and Visualization: Create a network file where significantly correlated gene-protein pairs are represented as edges. Import this file into network visualization software such as Cytoscape [22]. Genes and proteins are represented as nodes, and the correlation strength can be visualized by edge weight (thickness) and sign (color).

- Network Analysis and Interpretation: Analyze the resulting network to identify highly connected nodes (hubs) that may represent key regulators. Perform functional enrichment analysis (e.g., GO, KEGG) on the gene-protein modules to infer their biological roles, especially in metabolic pathways.

Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Multi-Omics Experiments

| Reagent / Platform | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) | Separates and identifies proteins and metabolites based on mass-to-charge ratio [13]. | Proteomics and metabolomics data generation. |

| RNA-Seq Platforms | High-throughput sequencing of RNA transcripts to quantify gene expression levels. | Transcriptomics data generation. |

| Cytoscape | An open-source software platform for visualizing complex molecular interaction networks [22]. | Visualization and analysis of integrated gene-protein networks. |

| Weighted Correlation Network Analysis (WGCNA) | R package for performing weighted correlation network analysis [22]. | Identification of co-expressed gene modules linked to protein data. |

| Size Exclusion and Ion Exchange Chromatography | Chromatographic techniques to separate protein-metabolite complexes based on size and charge [19]. | Mapping protein-metabolite interactions (PMIs). |

Integration in the Context of Metabolite-Metabolite Interaction Networks

The integration of proteomics and transcriptomics provides a causal bridge between genetic regulation and the structure of metabolite-metabolite interaction networks. Proteins, especially enzymes, are the direct architects and regulators of metabolic networks. By integrating transcriptomic and proteomic data, researchers can move beyond descriptive correlation to mechanistic understanding, distinguishing between scenarios where changes in metabolite abundance are driven by transcriptional regulation of enzymes versus post-translational modulation of enzyme activity [22] [19]. For example, a study in E. coli that integrated chromatographic techniques to map protein-metabolite interactions (PMIs) discovered an inhibitory interaction between lumichrome and orotate phosphoribosyltransferase (PyrE), thereby linking flavins to pyrimidine synthesis and biofilm formation [19]. This finding exemplifies how integrating proteomic data (protein-metabolite interactions) with other omics layers can elucidate functional metabolic controls.

The following diagram illustrates how different omics layers contribute to the characterization of a metabolite-metabolite interaction network, with proteomics and transcriptomics providing the crucial intermediate layers of biological information.

Applications in Drug Discovery and Biomedical Research

The integration of proteomics and transcriptomics has become a powerful tool in translational medicine and drug discovery, enabling several key applications:

- Target Identification and Validation: Multi-omics integration helps distinguish causal disease drivers from passive associations. While genomics can identify disease-associated mutations, layering transcriptomics and proteomics data confirms which mutations lead to functional changes in protein expression or activity, thereby revealing druggable targets with higher confidence [20] [21].

- Disease Subtyping and Biomarker Discovery: Integrating multiple omics layers allows for a more refined classification of complex diseases. Patient stratification based on integrated molecular profiles (e.g., combining mRNA expression and protein abundance) can identify subtypes with distinct clinical outcomes and therapeutic responses, facilitating personalized treatment strategies [21].

- Understanding Drug Mechanisms and Resistance: Analyzing changes in both the transcriptome and proteome in response to drug treatment provides a systems-level view of drug mechanism of action and the emergence of resistance. This can reveal compensatory pathways that are activated when a primary target is inhibited, pointing to rational combination therapies [20].

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite its promise, the integration of transcriptomics and proteomics faces several significant barriers. A primary challenge is data integration complexity, as different omics layers produce heterogeneous data with varying scales, resolutions, and noise levels [23] [21]. For instance, the disconnect between mRNA abundance and protein levels—where the most abundant protein may not correlate with high gene expression—makes integration difficult [23]. Furthermore, sensitivity differences between technologies mean a gene detected at the RNA level may be missing in the proteomics dataset due to limited spectral coverage [23]. Other hurdles include the high cost of comprehensive multi-omics profiling, infrastructure limitations for storing and processing enormous data volumes, and regulatory and privacy concerns that limit data sharing [20].

Looking ahead, the field is moving towards more sophisticated spatial and single-cell multi-omics technologies. These approaches map molecular activity at the level of individual cells within their tissue context, revealing cellular heterogeneity that bulk analyses cannot detect [20]. This will be critical for diseases like cancer. The synergy of multi-omics with artificial intelligence (AI) is also set to deepen, with machine learning models becoming adept at predicting how combinations of genetic, transcriptomic, and proteomic changes influence disease progression and drug response [20] [24]. Finally, investments in standardized data formats and interdisciplinary repositories will be crucial for overcoming current bottlenecks and fully realizing the potential of integrated multi-omics in biomedical research [20] [21].

Building and Applying Metabolic Networks: Techniques and Real-World Implementations

Metabolite-metabolite interaction networks are foundational to systems biology, providing critical insights into the functional state of an organism that is closely linked to its phenotype. The reconstruction of these networks relies heavily on statistical measures to quantify associations between metabolites. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of three core correlation-based approaches—Pearson correlation, Spearman rank correlation, and Gaussian Graphical Models (GGMs). Within the context of metabolomics research, we detail their theoretical foundations, computational methodologies, performance characteristics, and practical applications in elucidating biological mechanisms and identifying potential therapeutic targets. Framed within a broader thesis on metabolic network analysis, this review serves as a comprehensive resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals navigating the complexities of interaction inference in high-dimensional biological data.

Biological systems are inherently interconnected, and their complexity is often represented graphically as networks where nodes represent biological entities (e.g., genes, proteins, metabolites) and edges represent their physical, biochemical, or functional interactions [1]. Among these entities, metabolites hold a particularly significant position as they exhibit a closer relationship to an organism's phenotype compared to genes or proteins and can amplify small changes occurring at other omics levels [1]. Metabolic networks, complex systems comprising hundreds of metabolites and their interactions, play a critical role in mediating energy conversion and chemical reactions within cells [1].

The accurate inference of these interactions from observed metabolomic data is a central challenge in systems biology. Association measures form the backbone of network reconstruction, and the choice of method can profoundly impact the biological interpretation of the resulting network. This guide focuses on three pivotal correlation-based approaches. Pearson and Spearman correlations are classical measures of marginal association, widely used for their simplicity and interpretability. In contrast, Gaussian Graphical Models (GGMs) represent a more advanced framework for estimating conditional dependencies, effectively distinguishing direct from indirect interactions [25] [26]. Understanding the properties, applications, and limitations of these methods is essential for any rigorous investigation of metabolite-metabolite interaction networks.

Theoretical Foundations

Correlation as a Measure of Association

Correlation-based metabolic networks utilize the statistical correlations between metabolite concentrations to establish connectivity, simplifying multidimensional data while preserving interpretive information [1]. In such a network, a connection (edge) is established between two metabolites if the absolute value of their correlation coefficient exceeds a predefined threshold [1].

Pearson Correlation: The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient measures the strength and direction of a linear relationship between two variables. For a metabolite (x) and a microbe (y) measured across (n) samples, it is calculated as: ( r = \frac{\sum{i=1}^{n}(xi - \bar{x})(yi - \bar{y})}{\sqrt{\sum{i=1}^{n}(xi - \bar{x})^2}\sqrt{\sum{i=1}^{n}(y_i - \bar{y})^2}} ) where ( \bar{x} ) and ( \bar{y} ) are the sample means [27]. The coefficient ranges from -1 (perfect negative correlation) to +1 (perfect positive correlation).

Spearman Rank Correlation: The Spearman rank-order correlation is a non-parametric measure that assesses how well the relationship between two variables can be described using a monotonic function. It is calculated by applying the Pearson correlation formula to the rank-ordered values of the variables [1] [27]. This makes it more robust to outliers than Pearson correlation.

Partial Correlation and GGMs: A fundamental limitation of Pearson and Spearman correlations is that they measure marginal associations, which can be driven by indirect effects mediated by other variables in the network. Gaussian Graphical Models address this by estimating conditional dependencies [25] [26]. The partial correlation between variables (Xi) and (Xj) is a measure of their conditional association, given all other variables in the dataset, denoted as (X{-i,-j}). It is defined as: ( \rho{Xi, Xj \mid X{-i,-j}} = \frac{\text{Cov}[Xi, Xj \mid X{-i,-j}]}{\sqrt{\text{Var}[Xi \mid X{-i,-j}]}\sqrt{\text{Var}[Xj \mid X{-i,-j}]}} ) In the context of a GGM, which assumes the data follows a multivariate normal distribution, a zero partial correlation is equivalent to the conditional independence of the two variables given all others [25]. The edge set of a GGM is therefore defined by the set of all metabolite pairs with non-zero partial correlation [25]. The model is parameterized using the precision matrix (the inverse of the covariance matrix, (\Theta = \Sigma^{-1})), where (\theta{ij} = 0) if and only if the partial correlation between (Xi) and (X_j) is zero [25].

Comparative Strengths and Limitations

Table 1: Comparison of Correlation-Based Approaches for Metabolic Network Inference

| Feature | Pearson Correlation | Spearman Correlation | Gaussian Graphical Model (GGM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship Type | Linear | Monotonic | Linear (Conditional) |

| Dependency Type | Marginal | Marginal | Conditional |

| Handling of Indirect Effects | Poor; cannot distinguish from direct effects | Poor; cannot distinguish from direct effects | Excellent; infers direct effects by correcting for all other nodes |

| Data Distribution | Sensitive to outliers | Robust to outliers | Assumes multivariate normality |

| Computational Complexity | Low | Low | High, especially in high-dimensional settings |

| Interpretation | Simple | Simple | More complex; an edge implies a direct relationship |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for Correlation-Based Network Construction

The following step-by-step protocol outlines the process for constructing a metabolite-metabolite association network using correlation measures, as derived from common practices in the field [1] [28].

- Data Preprocessing: Prepare the metabolomic data matrix (samples × metabolites). Perform necessary steps including normalization, missing value imputation, and data transformation (e.g., log-transformation) to stabilize variance and improve normality.

- Correlation Calculation: For every pair of metabolites in the dataset, compute the association measure.

- For a Pearson-based network, calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient for all metabolite pairs.

- For a Spearman-based network, calculate the Spearman rank correlation coefficient for all metabolite pairs.

- Threshold Application: Define a significance threshold for the correlation coefficient (e.g., based on p-values from a permutation test or a fixed absolute value like 0.6). An edge is established between two metabolites if their correlation coefficient meets or exceeds this threshold.

- Network Construction: Create an adjacency matrix from the thresholded correlations. This matrix serves as the input for network visualization and analysis software (e.g., Cytoscape).

- Differential Connectivity Analysis (Optional): To compare networks between two conditions (e.g., healthy vs. diseased): a. Construct separate correlation networks for each condition. b. For each metabolite, calculate its weighted connectivity within each network, defined as the sum of the absolute values of its correlations with all other metabolites [28]. c. Compare the connectivity of each metabolite between the two conditions using a permutation test to assess statistical significance [28].

Diagram 1: Workflow for constructing a correlation-based metabolic network.

Protocol for GGM-Based Network Inference

Inferring a network using GGMs involves estimating the precision matrix, which encodes the conditional independence structure. The following protocol is adapted from high-dimensional omics analyses [25] [29].

- Data Preparation and Assumption Checking: As with correlation networks, preprocess the metabolomic data. Check the assumption of multivariate normality. While GGMs are somewhat robust to mild violations, severe deviations may require data transformation or the use of non-paranormal methods (Gaussian copula models).

- Precision Matrix Estimation: In high-dimensional settings (where the number of metabolites (p) is large relative to the sample size (n)), direct inversion of the sample covariance matrix is infeasible. Use regularized methods to estimate a sparse precision matrix.

- Method Selection: Common approaches include the Graphical Lasso (glasso) which uses an L1-penalty to encourage sparsity in the precision matrix [25], or the Scaled Lasso used in the FastGGM algorithm [29].

- Implementation: Utilize available R packages (e.g.,

FastGGM,BGGM,huge) to perform the penalized estimation [1] [29].

- Statistical Inference on Edges: Extract the partial correlation matrix from the estimated precision matrix. To determine the statistical significance of each inferred edge (i.e., whether a partial correlation is non-zero), calculate p-values and confidence intervals. The FastGGM algorithm, for instance, provides asymptotically normal estimators for this purpose, enabling rigorous inference [29].