Navigating the Data Deluge: Key Challenges and Solutions in Untargeted Mass Spectrometry Metabolomics Data Mining

Untargeted mass spectrometry metabolomics generates vast, complex datasets, presenting significant bottlenecks in data mining that hinder biological insight and clinical translation.

Navigating the Data Deluge: Key Challenges and Solutions in Untargeted Mass Spectrometry Metabolomics Data Mining

Abstract

Untargeted mass spectrometry metabolomics generates vast, complex datasets, presenting significant bottlenecks in data mining that hinder biological insight and clinical translation. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, addressing foundational data complexities, methodological normalization and annotation strategies, practical troubleshooting for optimization, and rigorous validation approaches. By synthesizing current research and multi-laboratory findings, we outline a systematic workflow to enhance data reliability, improve metabolite annotation, and ultimately unlock the full potential of metabolomics in biomarker discovery and precision medicine.

Understanding the Data Landscape: Core Complexities in Untargeted Metabolomics

In untargeted mass spectrometry metabolomics, the biological variation of interest is inevitably confounded with unwanted variation, presenting a significant challenge for data mining and biological interpretation [1]. This unwanted variation arises from multiple sources, including batch effects during instrumental analysis, long runs of samples leading to signal drift, and confounding biological variation not related to the factors under investigation [1] [2]. If not properly addressed, these factors can lead to falsely identifying differentially abundant metabolites, failing to detect true biological signals, generating spurious correlations, creating artificial clustering patterns, and yielding poor classification results [1]. Understanding and correcting for these variations is therefore not merely a technical formality but a fundamental prerequisite for obtaining biologically meaningful results from your metabolomics studies.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Batch Effects and Signal Drift

Q: My principal component analysis (PCA) shows clustering by batch date rather than biological group. What strategies can I use to correct for this?

- A: Batch effects are a common issue in large-scale studies where samples must be analyzed across multiple batches [3]. To address this:

- Incorporate Quality Control (QC) samples throughout your run. These can be pooled biological samples or externally purchased QCs that are representative of your sample matrix [1]. These QCs are used to monitor and correct for systematic shifts between batches.

- Apply inter-batch normalization algorithms during data processing. Methods such as QC-SVRC normalization and QC-norm use the data from the QC samples to mathematically correct for the batch-to-batch systematic error [4] [3].

- Ensure proper randomization of your biological samples across batches during the experimental design phase to avoid confounding batch effects with your factors of interest.

- A: Batch effects are a common issue in large-scale studies where samples must be analyzed across multiple batches [3]. To address this:

Q: I've observed a significant drift in signal intensity over the course of a long sample sequence. How can I stabilize this?

- A: Signal drift is often due to instrumental factors such as contamination of the ionization source [3].

- Implement a rigorous conditioning and cleaning protocol for the ionization source between batches.

- In your analysis sequence, include regular injections of QC samples (e.g., after every 5-10 experimental samples). The response of these QCs over time provides a model of the instrumental drift, which can be used for post-acquisition correction [3].

- Use multiple internal standards that are spiked into every sample. The stable, known concentrations of these standards can help track and correct for sensitivity fluctuations [1] [5].

- A: Signal drift is often due to instrumental factors such as contamination of the ionization source [3].

Sample Preparation and Technical Variation

- Q: How can I minimize technical variation introduced during sample preparation?

- A: Sample preparation is a critical source of technical variation that can impact downstream label-free quantitation [6].

- Standardize protocols meticulously. Use the same reagents, equipment, and timing across all samples.

- Use appropriate internal standards early. Add isotopically-labeled internal standards (e.g., l-Phenylalanine-d8, l-Valine-d8) at the very beginning of the extraction process. This helps account for losses during preparation and variations in matrix effects [5].

- Choose MS-compatible reagents. Avoid reagents like sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) or polyethylene glycol (PEG) that can inhibit digestion enzymes, cause ion suppression, or are incompatible with LC-MS/MS. Instead, consider alternatives like sodium deoxycholate (SDC) which has been validated for reproducible sample preparation without interfering substances [6].

- A: Sample preparation is a critical source of technical variation that can impact downstream label-free quantitation [6].

Biological Variation and Normalization

Q: My study involves urine samples with varying concentration levels. How can I account for this unwanted biological variation?

- A: Dilution differences in biofluids like urine are a classic example of unwanted biological variation.

- Traditional total ion count or median normalization relies on the assumption that the total metabolite abundance is constant across all samples (the self-averaging property), which often does not hold true [1].

- A more robust approach is to use quality control metabolites—metabolites that are present in your biological samples and are exposed to the unwanted variation, but are scientifically justified to be unassociated with the factors of interest. Methods like RUV-2 (Remove Unwanted Variation) use these metabolites to statistically accommodate the unwanted biological variation while retaining the biological variation of interest [1].

- A: Dilution differences in biofluids like urine are a classic example of unwanted biological variation.

Q: When should I use a single internal standard versus multiple internal standards for normalization?

- A: The use of a single internal standard (SIS) is generally inadequate because the variation it captures depends on its own chemical properties, leading to highly variable normalized results [1]. We strongly support the use of multiple internal standards [1]. Methods like the Average of Multiple Internal Standards (AIS), NOMIS, and CCMN use a combination of standards, providing a more comprehensive correction for unwanted variation across different metabolite classes and retention times [1] [3].

Comparison of Normalization Methods for Untargeted Metabolomics

The table below summarizes common normalization approaches, their mechanisms, and their suitability for different experimental scenarios.

Table 1: Normalization Methods for Handling Unwanted Variation in Metabolomics Data

| Method | Brief Description | Key Considerations | Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scaling Methods (Median, Total Ion Current) | Scales each sample by a specific factor (e.g., median, sum) [1]. | Relies on the self-averaging property, which is often invalid [1]. | Not suitable when self-averaging does not hold; applicable to supervised & unsupervised analysis [1]. |

| Single Internal Standard (SIS) | Normalizes using a single spiked-in compound [1]. | Leads to highly variable results; cannot remove unwanted biological variability [1]. | Applicable to supervised & unsupervised analysis [1]. |

| Average of Multiple Internal Standards (AIS) | Uses the average response of several internal standards [1]. | More robust than SIS; cannot remove unwanted biological variability [1]. | Applicable to supervised & unsupervised analysis [1]. |

| NOMIS / CCMN | Uses an optimal combination of multiple internal standards, accounting for factors like cross-contribution [1]. | More complex; CCMN requires factors of interest to be known [1]. | NOMIS: Supervised & unsupervised. CCMN: Supervised only [1]. |

| RUV-2 / RUV-random | Uses quality control metabolites or samples to model and remove unwanted variation [1]. | RUV-2 requires factors of interest; RUV-random is suitable for unsupervised analysis like clustering [1]. | RUV-2: Supervised only. RUV-random: Unsupervised & supervised [1]. |

| QC-Based Normalization (e.g., QC-SVRC) | Uses quality control samples to model and correct for systematic drift and batch effects [3]. | Requires careful preparation of representative QC samples and a well-designed run sequence [3]. | Essential for large-scale, multi-batch studies [3]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Robust Workflow for Large-Scale Studies

The following protocol outlines a systematic approach for a large-scale untargeted metabolomics study using LC-QToF-MS, designed to minimize and correct for unwanted variation [3].

Sample Preparation and Internal Standards

- Extraction: Prepare samples in small, randomized sets to maintain consistency. Use a pre-chilled extraction solvent (e.g., acetonitrile:methanol) to precipitate proteins and extract metabolites [5].

- Internal Standards: Spike a mixture of multiple, stable isotopically-labeled internal standards into each sample at the beginning of the extraction process. This mixture should cover a broad range of metabolite classes and retention times (e.g., deuterated carnitines, amino acids, lipids) to monitor the entire process [3] [5].

Instrumental Analysis and Batch Design

- Mobile Phase: Prepare large, single batches of mobile phases (e.g., 5L) for the entire study to avoid formulation variations [3].

- Batch Sequence: For each batch, use a structured sequence:

- Start with no-injection runs and blanks (extraction solvent) to condition the system and identify background signals [3].

- Inject multiple QCs (e.g., 10) for initial system conditioning.

- Analyze samples in a randomized order, interspersing a QC injection after every 5-10 experimental samples to monitor performance [3].

- Include replicates of a subset of case samples across all batches to assess technical reproducibility and normalization success [3].

- Source Maintenance: Clean the MS ionization source between batches to prevent signal drop-off, but avoid cleaning the chromatographic column between batches to maintain consistent retention times [3].

Data Processing and Normalization

- Pre-processing: Perform peak picking, alignment, and integration using appropriate software (e.g., TargetLynx, XCMS) [7].

- Intra-batch Drift Correction: First, correct for signal drift within each batch using the data from the frequently injected QCs with an algorithm like QC-SVRC [3].

- Inter-batch Normalization: Combine the batches and apply an inter-batch normalization method (e.g., QC-Norm) to remove systematic differences between batches, using the pooled QC samples as a reference [3].

- Assessment: Evaluate the success of normalization by checking if the QC samples cluster tightly in a PCA plot and if the variance explained by the "batch" factor is minimized.

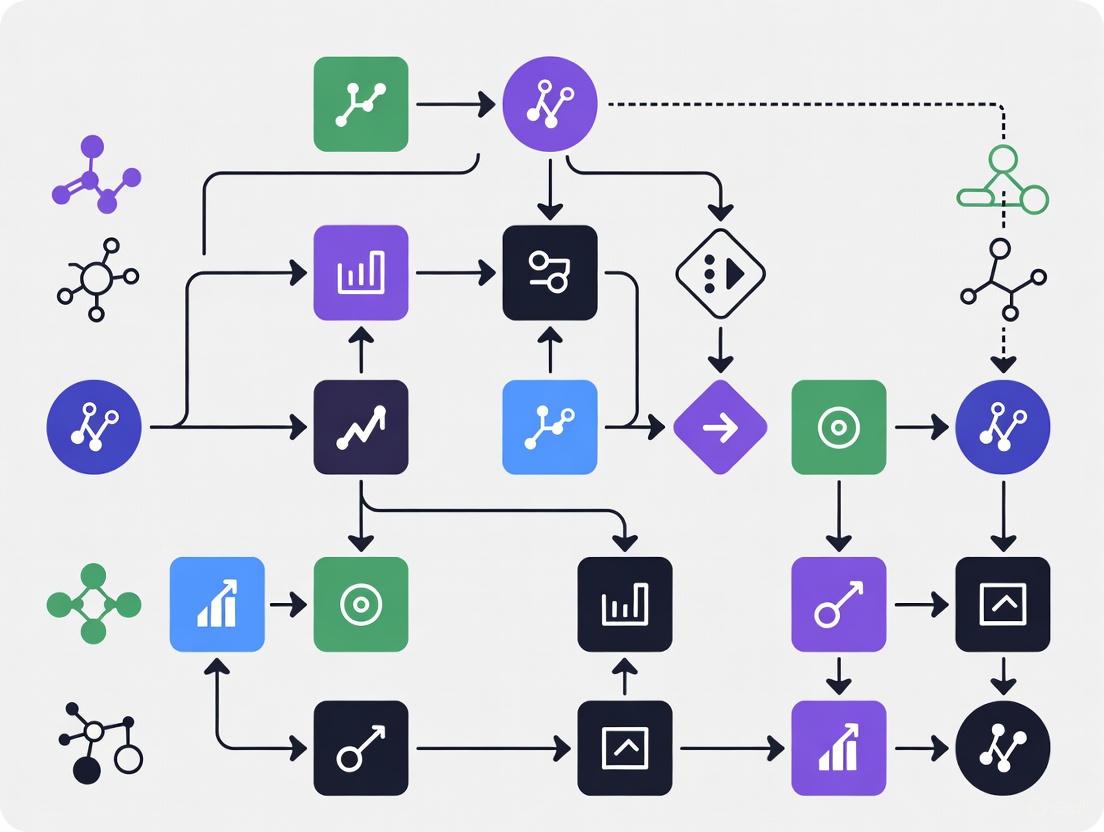

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Metabolomics Analysis with Batch Correction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolomics Workflows

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Spiked into samples to monitor extraction efficiency, matrix effects, and instrumental performance. Used for normalization. | l-Phenylalanine-d8, l-Valine-d8; Deuterated lipids (e.g., LPC, sphingolipids) [3] [5]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Injected repeatedly to monitor signal stability, correct for instrumental drift, and normalize batch effects. | Pooled biological samples from the study population or commercially available reference material [1] [3]. |

| MS-Compatible Detergents | For cell/tissue lysis and protein digestion in sample preparation without causing ion suppression or LC-MS interference. | Sodium Deoxycholate (SDC) - an effective alternative to SDS [6]. |

| Chromatography Solvents | High-purity mobile phases for LC-MS separation to reduce chemical noise and background. | LC/MS-grade Water, Acetonitrile, Methanol, Formic Acid [5]. |

| HILIC Chromatography Column | Separates polar, hydrophilic metabolites that are often key players in central carbon metabolism and mitochondrial function. | Waters Atlantis HILIC Silica Column or equivalent [5]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is metabolite identification considered a major bottleneck in untargeted metabolomics? Accurate metabolite annotation is a major bottleneck because the process is inherently complex. There is no single platform or method to analyze the entire metabolome of a biological sample, largely due to the wide concentration range of metabolites and their extensive chemical diversity [7]. Furthermore, the complexity of LC-MS data, which results from combinations of various chromatographic and mass spectrometric acquisition methods, has led to diverse, often non-standardized workflows that frequently involve manual curation [8].

Q2: What are the different confidence levels for reporting metabolite identities? The Metabolomics Standards Initiative (MSI) proposes four levels of confidence for metabolite identification [9]:

- Level 1: Identified Metabolites. Confidence is achieved by matching two or more orthogonal properties (e.g., retention time and MS/MS spectrum) of the experimental data to an authentic standard analyzed in the same laboratory.

- Level 2: Presumptively Annotated Compounds. Annotation is based on spectral similarity to a library or standard, without confirmation from a reference standard in-house.

- Level 3: Presumptively Characterized Compound Classes. Annotation is to a compound class based on characteristic structural properties (e.g., a lysophosphatidylcholine).

- Level 4: Unknown Compounds. These compounds can be distinguished and differentiated but cannot be currently identified.

Q3: Why might no metabolites be identified in my sample, despite detecting many spectral features? This is chiefly a limitation of the available database [10]. If your sample is enriched with specific peaks compared to a control but no metabolites are identified, it indicates that the detected features are not present in the spectral library used for the search. Other reasons can include sample dilution, loss of metabolites during the extraction procedure, or solubility issues during the reconstitution of the dried sample [10].

Q4: How does biological variability impact the power of a metabolomics study? The human metabolome is highly dynamic, fluctuating due to circadian rhythms, diet, and other factors [11]. This within-individual variability, coupled with technical measurement error, can account for the majority of the total variance for many metabolites [12]. This high variability reduces the statistical power to detect associations with disease, necessitating larger sample sizes to identify effects of moderate size reliably [11] [12].

Q5: What kind of results can I expect from an untargeted metabolomics analysis? You will typically receive a report with a list of identified metabolites (where possible), mass over charge (m/z) values, chromatographic retention times (RT), and peak areas/intensities [10]. For an untargeted workflow, you will also receive a list of all detected features (m/z and RT) without metabolite identifications. Depending on the experimental design, statistical analyses such as fold-change and p-values may also be provided [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Improving Metabolite Annotation Confidence

Problem: Low confidence in metabolite identifications, leading to unreliable biological interpretations.

Solution: Adopt a tiered approach to increase annotation confidence.

- Step 1: Optimize Pre-processing Parameters. The parameters used in data pre-processing (e.g., intensity threshold and mass tolerance) directly influence the number and quality of features defined for subsequent annotation [13]. Explore different settings to ensure a robust and representative dataset.

- Step 2: Utilize Multi-platform Analysis. Combine data from separate UPLC-MS platforms optimized for different physicochemical properties. For example, analyzing both methanol and chloroform/methanol extracts can extend coverage over diverse metabolite classes such as amino acids, lipids, and organic acids [7].

- Step 3: Leverage Public and In-house Libraries. Use a combination of public databases (e.g., HMDB, KEGG, LIPID MAPS) and, crucially, in-house spectral libraries generated from authentic standards for the highest confidence (Level 1) [9] [10].

- Step 4: Report According to MSI Guidelines. Clearly state the confidence level (1-4) for every reported metabolite in your publications to ensure transparency and reproducibility [9].

Guide: Managing Technical and Biological Variability

Problem: High variability obscures biologically relevant signals.

Solution: Implement rigorous quality control and study design.

- Step 1: Incorporate Quality Control (QC) Replicates. Use QC samples (e.g., pooled from all samples) to monitor instrument stability. Data from QC samples are used to balance analytical bias, correct for signal noise, and remove metabolite features with unacceptably high technical variance [9].

- Step 2: Apply Robust Normalization. Perform intra- and inter-batch normalization to correct for signal drift, especially in large-scale studies where analysis over multiple batches is unavoidable [14].

- Step 3: Account for Biological Variability in Study Design. For epidemiological studies, a single measure may not capture an individual's "usual" metabolite level [11]. Where feasible, collect multiple samples per individual or consider pooling samples from different time points to better estimate long-term average levels [11].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: A Multi-platform UPLC-MS Metabolomic Workflow

This protocol, adapted from a study on aging, is designed for extensive coverage of the serum metabolome [7].

- Sample Preparation: Fractionate serum samples into pools of species with similar properties using appropriate combinations of organic solvents (e.g., methanol and chloroform/methanol) [7].

- Instrumental Analysis: Analyze the extracts using three separate UPLC-MS platforms:

- Platform 1: UPLC-single quadrupole-MS for amino acid analysis.

- Platform 2: UPLC-time-of-flight-MS for methanol extracts (covering non-esterified fatty acids, acyl carnitines, bile acids, steroids, etc.).

- Platform 3: UPLC-time-of-flight-MS for chloroform/methanol extracts (covering glycerolipids, sphingolipids, diacylglycerophospholipids, etc.).

- Data Pre-processing: Process raw data using software (e.g., TargetLynx) for peak picking, which includes defining metabolic features based on retention time and exact mass [7].

Data on Variability and Statistical Power

The following table summarizes key variability metrics for metabolites, which are critical for designing powerful and reproducible studies.

Table 1: Sources of Variability in Metabolite Measurements

| Metric | Definition | Implication for Research | Typical Value Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technical Variance ($σ_{tech}^2$) | Variance introduced by laboratory measurement error. | High technical variance reduces reliability and increases false positives/negatives. | Median ICC for technical reliability can be ~0.8 [12]. |

| Within-individual Variance ($σ_{within}^2$) | Variability over time within a single person. | A single measurement may not represent the "usual" level, weakening observed associations with disease [11]. | Combined with technical variance, it accounts for the majority of total variance for 64% of metabolites [12]. |

| Between-individual Variance ($σ_{between}^2$) | Variance of the "usual" metabolite level between subjects in a population. | This is the variance of primary biological interest for identifying disease biomarkers. | The proportion of biological variance attributed to between-individual variance ($R_{B}$) varies by metabolite [11]. |

| Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) | The proportion of total variance attributed to biological variance (between- + within-person). | High ICC indicates high laboratory reproducibility. | Median ICC ~0.8 for technical replicates [11]. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Metabolite Annotation

| Reagent / Solution / Tool | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| Authentic Chemical Standards | Used to generate in-house spectral libraries for Level 1 metabolite identification by matching retention time and MS/MS spectrum [10]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Pool | A pooled sample from all subjects, repeatedly analyzed throughout the batch to monitor and correct for instrumental drift [9] [14]. |

| Liquid Chromatography (LC) Systems | Reduces sample complexity by separating metabolites before they enter the mass spectrometer, improving detection and quantification [9]. |

| Internal Standards (Labeled) | Stable isotope-labeled compounds added to correct for variability during sample preparation and analysis [14]. |

| Public Databases (HMDB, KEGG, LIPID MAPS) | Used for initial, presumptive annotation (Level 2-3) of metabolites by comparing accurate mass and fragmentation patterns [9] [7]. |

| Data Pre-processing Software (e.g., XCMS, MZmine) | Converts raw instrumental data into a peak intensity matrix by performing peak detection, alignment, and retention time correction [9]. |

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Metabolite Annotation Confidence Journey

Metabolomics Data Mining Pipeline

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the main sources of instrumental drift in mass spectrometry-based metabolomics? Instrumental drift in mass spectrometry-based metabolomics is primarily caused by fluctuations in retention time (RT) and signal intensity over the course of an analytical run. Specific causes include minor degradation of column performance, small leaks in the chromatography system, interactions between compounds in the sample matrix, and changes in instrument sensitivity due to maintenance, ion source contamination, or filament replacement [15] [16]. These variations are particularly problematic in large cohort studies where samples are analyzed over extended periods.

2. How do biological confounders affect metabolomics studies, specifically in blood samples? Biological confounders are patient-specific variables that can significantly alter metabolic profiles, potentially masking genuine changes due to disease or intervention. Key confounders for blood metabolomics include age, sex, diet, lifestyle, and health status. Pre-analytical conditions such as sample handling, the type of collection containers used, and storage conditions also introduce significant variation [17]. These factors must be carefully controlled and documented to ensure data reliability and inter-laboratory comparability.

3. Why are Quality Control (QC) samples considered vital for managing instrumental drift? Intrastudy QC samples, typically a pooled mixture of all biological samples, are injected at regular intervals throughout the analytical sequence. They serve three critical functions:

- System Conditioning: The initial injections help equilibrate the chromatographic system, ensuring stable performance [15].

- Monitoring Precision: As all QCs are identical, they allow researchers to calculate quality metrics like the Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) to assess measurement precision over time [15].

- Modeling Drift: The data from intermittently measured QCs provides a quantitative record of how instrument performance changes, enabling mathematical modeling and correction of systematic errors for the entire dataset [15] [16].

4. What is the difference between intra-batch and inter-batch effects? A batch is defined as a set of samples processed and analyzed uninterrupted using the same instrument and protocol. Intra-batch effects are sensitivity drifts that occur within a single batch, while inter-batch effects are variations introduced between different batches, often due to instrument maintenance, column replacement, or different operators [15]. Both can be stronger than the biological effects of interest, leading to false discoveries if not corrected.

5. Which algorithms are effective for correcting batch effects and instrumental drift? Several algorithms of varying complexity can be used to correct data based on QC samples. The performance of these methods can be evaluated using metrics like the reduction in QC RSD.

Table 1: Comparison of Batch-Effect Correction Algorithms

| Algorithm | Description | Key Findings from Studies |

|---|---|---|

| TIGER | A normalization method using an ensemble learning architecture. | Demonstrated the best overall performance in one study, effectively reducing the RSD of QCs and achieving the highest predictive accuracy with machine learning classifiers [15]. |

| QC-RSC | A regression-based method using a penalized cubic smoothing spline. | A robust and commonly used approach for modeling and correcting drift [15]. |

| Random Forest (RF) | A machine learning algorithm based on an ensemble of decision trees. | Provided the most stable correction model for long-term, highly variable data over 155 days, outperforming other methods [16]. |

| Support Vector Regression (SVR) | A variant of Support Vector Machines for numerical prediction. | Can be unstable for highly variable data, sometimes leading to over-fitting and over-correction [16]. |

| Median Normalization | A simple and easy-to-implement method. | A baseline method, though may be less effective than more complex algorithms for severe drift [15]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Mitigating Instrumental Drift in Large-Scale Studies

Problem: Significant technical variation in large untargeted metabolomics studies leads to unreliable data and false discoveries.

Solution: Implement a robust workflow incorporating QC samples and algorithmic correction.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Drift Correction

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Intrastudy QC Samples | A pooled sample representing the aggregate metabolite composition of the entire study. Serves as the cornerstone for monitoring and correcting instrumental drift [15]. |

| Conditioning QC Samples | A series of QC injections at the start of a sequence to equilibrate the column and mass spectrometer, ensuring system stability before analytical data acquisition [15]. |

| Chemical Standards (for artificial QCs) | Used to create artificial QC samples when it is impossible to generate intrastudy QCs from the biological samples. Should contain as many metabolites from different classes as possible dissolved in a dummy matrix [15]. |

Experimental Protocol:

- QC Preparation: Prepare intrastudy QC samples by combining equal aliquots from all biological samples in the study [15].

- Sequence Design: Start the analytical sequence with 4-8 conditioning QC injections to stabilize the system. Subsequently, inject QC samples regularly throughout the run (e.g., every 5-10 experimental samples) [15].

- Data Pre-processing: Process raw data using software (e.g., XCMS, MZmine) for peak picking, alignment, and integration [9].

- Drift Correction: Apply a batch-effect correction algorithm (see Table 1) using the data from the QC samples to model and remove technical variation from the entire dataset.

- Quality Assessment: Evaluate the success of the correction by calculating the RSD of metabolites in the QC samples before and after processing. A significant reduction indicates effective normalization [15].

The following diagram illustrates the core logic of this troubleshooting workflow:

Guide 2: Managing Biological Confounders in Blood Metabolomics

Problem: Biological and pre-analytical variations confound results, making it difficult to distinguish true biological signals from noise.

Solution: Adopt strict, standardized protocols for sample selection, collection, and preparation.

Experimental Protocol for Blood NMR Metabolomics:

- Sample Selection: Define clear inclusion/exclusion criteria for participants that account for key confounders like age, sex, and health status. Record all relevant metadata [17].

- Collection: Standardize the blood collection process. This includes specifying the type of anticoagulant-coated tube (e.g., EDTA, heparin) as this can affect the metabolic profile [15] [17].

- Handling & Storage: Establish and adhere to strict protocols for processing blood into plasma or serum, including temperature conditions and time-to-centrifugation/storage to prevent metabolite degradation [17].

- Data Reporting: Clearly document all pre-analytical procedures and participant metadata to enable proper covariate adjustment during statistical analysis and to enhance the reproducibility of the study [17].

The workflow for managing confounders spans from patient recruitment to data reporting, as shown below:

Troubleshooting Guide: Feature Detection in Untargeted Metabolomics

Q: Our multi-laboratory study shows high variability in the number of features detected from the same sample. What are the primary causes?

A: Inconsistent feature detection often stems from several technical sources. A 2025 multi-laboratory study analyzing an ashwagandha extract via LC-MS revealed that a significant portion of the detected "features" were not unique biological analytes. Instead, many resulted from in-source fragmentation, and the formation of different adducts, fragment ions, or in-source clusters. If these are not properly grouped during data preprocessing, they inflate the perceived sample complexity and introduce major inconsistencies between labs [18]. Other common causes include differences in instrumental drift correction and the data preprocessing software and parameters used [19].

Q: How can we improve consistency in annotating detected features across different teams?

A: Key strategies include improving data preprocessing and leveraging multiple evidence sources. Careful data preprocessing and feature grouping are critical to mitigate false positives from technical artifacts [18]. Furthermore, teams should incorporate multiple lines of evidence for annotation, including retention time prediction, in silico fragmentation, and literature verification, alongside spectral matching. Collaborative consensus, where annotations from various pipelines are combined, also significantly enhances confidence and creates a more comprehensive picture of the metabolome [18].

Q: What normalization methods are most effective for minimizing technical variation in a multi-laboratory setting?

A: The choice of normalization method depends on your experimental design and the type of variation you need to remove. The following table summarizes methods based on a 2017 GC-MS epidemiological study [19]:

| Method Type | Example Methods | Best For | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Control (QC)-Based | LOWESS, SVR, Batch Normalizer | Controlled experiments where technical variation (e.g., instrumental drift) is the primary concern. | Provides the highest data precision for technical signal correction over time [19]. |

| Model-Based | PQN, EigenMS | Epidemiological or complex biological studies with unwanted biological biases. | Effective at minimizing both technical and biological biases, improving clinical group classification [19]. |

| Internal Standard (IS)-Based | CRMN, NOMIS | Targeted analysis; can be used in untargeted GC-MS but has limitations. | Practical limit to the number of standards, leading to incomplete coverage of complex mixtures [19]. |

Experimental Protocols for Consistency

Reference Sample Preparation for Performance Assessment

A 2022 study developed a robust method to create paired tumor-normal reference materials for assessing NGS panels, which is analogous to needs in metabolomics [20].

- Cell Line Engineering: The mismatch repair (

MLH1,MSH2) and proofreading-associated DNA polymerase epsilon (POLE) genes were knocked down in a GM12878 cell line using CRISPR-Cas9 technology. Deficiencies in these pathways lead to genome instability and an accelerated accumulation of somatic mutations [20]. - Sample Preparation: A panel of 15 DNA reference samples was prepared from the engineered clones. This included samples with single, double, and triple gene knockdowns cultured for different durations (1 to 7 months), as well as mixtures of different clones to create specific variant allele frequency profiles. A matched normal sample (

SNC) was prepared from the original cell line [20]. - Establishing a Truth Set: A high-confidence reference dataset of 168 somatic mutations was established. For variants with high allele frequency (VAF ≥ 10%), whole-exome sequencing (WES) results were used. For lower-frequency variants (VAF < 10%), results from high-depth, high-performance oncopanels were used to define the truth set, overcoming WES limitations for low-AF detection [20].

Multi-Laboratory Study Design for Panel Assessment

- Sample Distribution: The prepared reference samples were shipped to participating clinical laboratories. All labs were provided the same coded samples with detailed instructions for storage and assay procedures [20].

- Data Collection and Analysis: Laboratories performed detection using their routine NGS oncopanels and workflows. They were required to submit variant calls (VCF files), aligned reads (BAM files), and detailed information on their panel parameters, sequencing procedures, and bioinformatics tools [20].

- Performance Metric Evaluation: The collective results were evaluated against the established truth set. Key performance metrics calculated included precision (the proportion of reported variants that are true positives) and recall (the proportion of true positives that were successfully detected), which can be combined into an F1-score [20].

Quantitative Data on Detection Consistency

Table 1: Performance Variability Across 56 Large NGS Panels This data, from a multi-lab study using engineered reference samples, reveals the scope of inconsistency in somatic mutation detection, a challenge directly analogous to feature detection in metabolomics. [20]

| Performance Metric | Range Across Panels | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Precision | 0.773 to 1.000 | Measures false positive rate. |

| Recall | 0.683 to 1.000 | Measures false negative rate. |

| Total Errors | 1306 (collectively) | For mutations with AF > 5%. |

| False Negatives (FNs) | 729 | Largest source of error. |

| False Positives (FPs) | 179 | - |

| Reproducibility Errors | 398 | - |

Table 2: Annotation Inconsistency in a Multi-Lab Metabolomics Study Findings from a 2025 study where 10 teams annotated the same LC-MS dataset of an ashwagandha extract. [18]

| Metric | Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Collectively Identified Analytes | 142 | The total potential metabolome coverage. |

| Per-Team Detection Rate | 24% to 57% | High variability in individual lab results. |

| Annotation Overlap | Highest for feature detection, diminished at ion species, chemical class, and definitive identity | Consistency decreases with increasing annotation specificity. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Reference Sample Preparation and Validation

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Used to knock down specific genes (e.g., MLH1, MSH2, POLE) in a parent cell line to generate cell lines with hypermutated genomes for use as reference materials [20]. |

| Paired Tumor-Normal Cell Lines | The engineered hypermutated cell line serves as the "tumor," while the original, unmodified cell line (e.g., Cas9-expressing GM12878) serves as the matched "normal" sample [20]. |

| LC-MS/MS Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents are critical for sample preparation (e.g., metabolite extraction) and mobile phase preparation to minimize background noise and ion suppression in mass spectrometry. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Added to samples during extraction to correct for variations in sample preparation and matrix effects, improving quantification accuracy [19]. |

| Pooled Quality Control (QC) Sample | A sample created by combining a small aliquot of every experimental sample. It is analyzed repeatedly throughout the analytical run to monitor instrument stability and correct for technical drift [19]. |

Experimental Workflow for Consistency Assessment

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for developing reference materials and assessing consistency across multiple laboratories, as described in the provided studies [18] [20].

Q: What are the common sources of false discoveries in feature and variant detection?

A: Based on the analysis of 56 NGS panels, the sources of error (false negatives and false positives) can be quantified [20]:

- Incorrect and Inadequate Filtering: This was the largest contributor to false discoveries. Overly aggressive or poorly designed bioinformatic filters can remove true positive variants, while insufficient filtering allows false positives to persist.

- Low-Quality Detection: Sequencing errors, low coverage in specific regions, or poor mapping quality can lead to both missed variants and incorrect variant calls.

- Cross-Contamination: Contamination between samples during library preparation or sequencing can introduce false positive variant calls.

- Low Allele Frequency (AF): Variants with an AF of less than 5% considerably influenced reproducibility and comparability among panels, making them a major challenge for consistent detection.

From Raw Data to Biological Insight: Methodological Strategies for Effective Data Mining

In untargeted mass spectrometry-based metabolomics, the presence of unwanted technical and biological variations can significantly hamper the identification of true differential metabolic profiles. These variations arise from multiple sources, including differences in sample collection, biomolecule extraction, instrument variability, signal drift, and batch effects. Data normalization serves as a critical preprocessing step to remove these unwanted variations while preserving biologically relevant information. The three primary normalization approaches—Internal Standard-based (IS-based), Quality Control-based (QC-based), and Model-based methods—each offer distinct mechanisms for addressing these challenges. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance and detailed protocols to help researchers select and implement the most appropriate normalization strategy for their specific experimental context.

Normalization methods in metabolomics can be broadly classified into three categories based on their underlying principles and requirements. Understanding the strengths and limitations of each category is essential for proper method selection.

Table 1: Categorization and Characteristics of Normalization Methods

| Method Category | Description | Key Examples | Primary Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Standard (IS)-based | Uses spiked-in chemical standards to estimate and correct technical variations | NOMIS, CCMN, SIS, CRMN | Targeted analyses; when stable isotope-labeled standards are available |

| Quality Control (QC)-based | Utilizes repeatedly analyzed pooled QC samples to monitor and correct temporal drift | QC-RLSC, LOWESS, SVR, MetNormalizer, Batch Normalizer | Large-scale studies with long analysis periods; batch effect correction |

| Model-based | Applies statistical models to the entire dataset without requiring additional samples | PQN, Quantile, VSN, EigenMS, Cyclic Loess | Studies with limited sample availability; when QC/IS not feasible |

Performance evaluations across multiple studies have revealed significant differences in how these methods handle various data characteristics. A comprehensive comparison of 16 normalization methods for LC-MS based metabolomics data categorized methods into three groups based on performance across sample sizes: superior, good, and poor performance groups. Specifically, VSN (Variance Stabilizing Normalization), Log Transformation, and PQN (Probabilistic Quotient Normalization) were identified as consistently top-performing methods, while Contrast Normalization consistently underperformed across all benchmark datasets [21].

Table 2: Normalization Method Performance Based on Evaluation Studies

| Normalization Method | Performance Ranking | Key Strengths | Noted Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| VSN | Superior | Reduces heteroscedasticity effectively | May over-correct in some datasets |

| PQN | Superior | Robust to dilution effects; works well with NMR and MS data | Assumes most metabolites remain unchanged |

| Quantile | Good (varies by study) | Excellent for transcriptomics; adapts well to metabolomics | Can distort biological variances |

| Cubic Splines | Good | Effective for temporal drift correction | Requires appropriate knot placement |

| Auto Scaling | Good (for GC/MS) | Overall best performance in GC/MS studies | Not always optimal for LC-MS data |

| Contrast | Poor | Theoretical basis from transcriptomics | Consistently underperforms in metabolomics |

The suitability of normalization methods depends heavily on the analytical platform. For GC/MS data, Auto Scaling and Range Scaling have demonstrated superior performance [21], while for UHPLC-MS data, research recommends PQN normalization combined with Random Forest missing value imputation and glog transformation for multivariate analysis [22].

Troubleshooting Common Normalization Issues

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How do I select the most appropriate normalization method for my LC-MS metabolomics dataset?

The choice depends on your experimental design, sample size, and data quality. For studies with quality control samples, QC-based methods (e.g., QC-RLSC) are optimal for correcting signal drift across batches. When internal standards are available, IS-based methods (e.g., NOMIS) provide compound-specific correction. For studies without QCs or ISs, model-based approaches like PQN or VSN are recommended. Evaluation tools such as NOREVA can objectively compare multiple normalization methods using criteria like reduction of intragroup variation and improvement in classification accuracy [23]. Performance also varies with sample size—VSN, Log Transformation, and PQN consistently perform well across various sample sizes, while methods like Contrast consistently underperform [21].

Q2: Why do I observe increased technical variation after normalization?

This can occur when using inappropriate normalization methods that introduce rather than reduce artifacts. For example, normalizing UHPLC-MS data with total sum scaling can increase variation when a few metabolites show large concentration changes, as this violates the "self-averaging" assumption [22]. Similarly, normalizing data with Contrast or Li-Wong methods may hardly reduce bias and fail to improve comparability between samples [21]. To resolve this, verify that your data meets the assumptions of your chosen method and consider alternative approaches. Using evaluation tools like NOREVA with multiple criteria can identify methods that increase technical variation [23].

Q3: How can I handle batch effects and signal drift in large-scale studies?

For large-scale studies analyzing hundreds to thousands of samples over extended periods, QC-based normalization is essential. Implement QC-RLSC (Robust LOESS Signal Correction) using systematically interspersed quality control samples [23]. Additionally, consider two-step approaches that first apply QC-based correction followed by data normalization. In one case study, the combination of qc-LOESS and cubic splines normalization most effectively reduced both within-batch and between-batch variation [24]. For GC/MS data with varying detectability thresholds across batches, mixture model normalization (mixnorm) specifically handles batch-specific truncation of low abundance compounds [25].

Q4: What causes inconsistent biomarker discovery after normalization?

Different normalization methods can produce conflicting results because they handle unwanted variations differently [23]. This occurs because each method makes different assumptions about the data structure and sources of variation. To ensure robust feature selection: (1) Apply multiple normalization methods and compare results, (2) Use spike-in compounds or validated markers as references when possible, and (3) Employ consistency scores to measure the overlap of identified markers across different data partitions [23]. NOREVA provides a consistency score that quantitatively measures the overlap of identified metabolic markers among different dataset partitions [23].

Q5: How should I handle missing values in my data before normalization?

The optimal approach depends on why data are missing. In untargeted metabolomics, missing values can occur because metabolites are: (1) truly absent, (2) below the limit of detection, or (3) not detected due to software limitations [22]. For univariate analysis, no imputation coupled with PQN normalization is recommended. For PCA, apply Random Forest imputation, and for PLS-DA, use K-nearest neighbors (KNN) imputation [22]. Avoid simple replacements (e.g., with zero or small values) without understanding the missingness mechanism. Studies show that missing values in metabolomics data are often Missing Not At Random (MNAR), requiring specialized handling [22].

Advanced Technical Issues

Q6: When should I use multiple internal standards instead of a single one?

Single internal standards may not adequately represent the chemical diversity of all metabolites in your sample. The NOMIS (Normalization using Optimal selection of Multiple Internal Standards) method addresses this by using multiple standards to find optimal normalization factors for each molecular species [26]. This approach is particularly valuable when analyzing chemically diverse compounds with different responses to experimental variations. NOMIS has demonstrated superior performance compared to single-standard methods or normalization by total intensity, especially for complex lipidomic profiles where different lipid classes exhibit distinct behaviors during extraction and ionization [26].

Q7: How can I evaluate normalization performance when true biological values are unknown?

When reference values or spike-in compounds are unavailable, use these evaluation criteria: (1) Reduction in intragroup variation measured by pooled CV or median absolute deviation, (2) PCA clustering of quality control samples, (3) Distribution of p-values in differential analysis (should be uniform for non-differential metabolites), and (4) Classification accuracy using SVM or PLS-DA [23]. The NOREVA tool implements five well-established criteria to ensure comprehensive evaluation from multiple perspectives [23]. Additionally, Relative Log Abundance (RLA) plots can visualize the tightness of sample distributions across groups after normalization [19].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: NOMIS Normalization Using Multiple Internal Standards

The NOMIS method optimally combines information from multiple internal standards to correct systematic errors.

Principles and Applications NOMIS addresses the limitation of single internal standards by modeling the systematic variation in measured intensities for each metabolite peak as a function of variation observed in multiple standard compounds. It is particularly effective for lipidomic profiling and complex mixture analysis where different compound classes exhibit varying responses to experimental conditions [26].

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Standard Selection: Spike each sample with 3-5 stable isotope-labeled internal standards representing different chemical classes and retention time regions.

- Data Acquisition: Perform LC-MS analysis following standard untargeted profiling protocols.

- Peak Detection and Alignment: Process raw data using tools like XCMS or mzMine to generate a peak intensity matrix.

- Model Training: Calculate normalization factors using the following approach:

- Let (X{ij}) represent the intensity of metabolite (i) in sample (j)

- Let (Z{sj}) represent the intensity of internal standard (s) in sample (j)

- Assume the multiplicative model: (X{ij} = mi × r{ij}(Z) × e{ij})

- Apply log transformation: (Y{ij} = μi + ρ{ij}(Ω) + ε{ij})

- Estimate correction factors (ρ_{ij}) as functions of the internal standard profiles [26]

- Application: Apply the calculated normalization factors to all metabolite intensities.

- Validation: Assess performance by measuring the reduction in coefficient of variation for technical replicates.

Technical Notes

- NOMIS can be applied as a one-step normalization for standard experiments or as a two-step method where normalization parameters are first calculated from a repeatability study

- The method can also guide analytical development by identifying optimal standard combinations for specific biological matrices [26]

Protocol 2: QC-RLSC for Signal Drift Correction

QC-based Robust LOESS Signal Correction is essential for large-scale studies where signal drift occurs over time.

Principles and Applications QC-RLSC uses repeatedly analyzed quality control samples to model and correct systematic temporal drift in metabolite intensities. It is particularly valuable for large-scale epidemiological studies and long-term projects where samples are analyzed over weeks or months [23].

Step-by-Step Procedure

- QC Sample Preparation: Create a pooled QC sample from all study samples or a representative subset.

- Experimental Design: Intersperse QC samples throughout the analysis sequence (every 5-10 experimental samples).

- Data Acquisition: Analyze all samples and QCs using standardized LC-MS methods.

- Drift Modeling: For each metabolite, fit a LOESS curve to the QC intensities as a function of injection order:

- Use the formula: (I{corrected} = I{observed} - f(t) + \bar{I}{QC})

- Where (f(t)) is the LOESS-fitted drift function and (\bar{I}{QC}) is the mean QC intensity

- Application: Apply the per-metabolite correction factors to all experimental samples.

- Quality Assessment: Verify correction by examining PCA plots of QC samples before and after normalization.

Technical Notes

- Optimal LOESS span parameters should be determined through cross-validation

- For large datasets (>1000 samples), consider batch-specific corrections followed by global alignment

- The statTarget R package provides implementation of QC-RLSC [23]

Protocol 3: Probabilistic Quotient Normalization (PQN)

PQN is a model-based approach that assumes most metabolite ratios between samples remain constant.

Principles and Applications PQN operates on the principle that biologically interesting concentration changes affect only parts of the metabolomic profile, while dilution effects influence all metabolites similarly. It is widely applicable to both NMR and MS-based metabolomics and does not require internal standards or quality control samples [19].

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Data Preparation: Compile peak intensity matrix with metabolites as rows and samples as columns.

- Reference Selection: Calculate the median spectrum across all samples to serve as reference.

- Quotient Calculation: For each sample, calculate quotients between metabolite intensities and reference intensities.

- Normalization Factor: Determine the median quotient for each sample.

- Application: Divide all metabolite intensities in each sample by its corresponding median quotient.

- Validation: Assess performance using RLA plots and reduction in overall variance.

Technical Notes

- PQN performs best when most metabolites remain unchanged between experimental conditions

- The method is particularly effective for urine metabolomics where dilution effects are prominent

- For optimal results with UHPLC-MS data, combine PQN with glog transformation and no scaling [22]

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Method Selection Workflow for Data Normalization

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolomics Normalization

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Function in Normalization | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Standards | Chemical Reagent | IS-based normalization; corrects extraction/ionization variance | Select compounds representing major chemical classes in your samples |

| Pooled Quality Control Sample | Biological Reagent | QC-based normalization; monitors instrumental drift | Prepare from equal aliquots of all study samples or representative pool |

| NOREVA | Software Tool | Comprehensive evaluation of normalization performance | Web tool comparing 24 methods using 5 criteria; http://server.idrb.cqu.edu.cn/noreva/ |

| MetaPre | Software Tool | Performance evaluation of 16 normalization methods | Specialized for LC-MS data; http://server.idrb.cqu.edu.cn/MetaPre/ |

| statTarget R Package | Software Tool | Implements QC-RLSC for signal drift correction | Includes batch effect correction and statistical analysis |

| MetaboAnalyst | Software Tool | Web-based platform with multiple normalization options | Provides 13 normalization methods but missing VSN and PQN |

Performance Evaluation Framework

Rigorous evaluation of normalization performance requires multiple criteria, as no single metric comprehensively captures all aspects of normalization effectiveness.

Table 4: Comprehensive Evaluation Criteria for Normalization Methods

| Evaluation Criterion | Measurement Approach | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Reduction of Intragroup Variation | Pooled CV, PEV, or PMAD | Lower values indicate better removal of technical noise |

| Effect on Differential Analysis | Distribution of p-values | Uniform distribution indicates proper control of false positives |

| Consistency of Marker Identification | Consistency score across data partitions | Higher scores indicate more robust feature selection |

| Classification Accuracy | AUC values from SVM models | Higher values indicate better preservation of biological signals |

| Correspondence with Reference | Correlation with spike-in compounds or validated markers | Better correspondence indicates more accurate normalization |

The NOREVA framework implements all five criteria, enabling researchers to objectively compare normalization methods and select the optimal approach for their specific dataset [23]. This multi-criteria evaluation is essential because methods performing well by one criterion may underperform by others. For example, while Quantile normalization might show good reduction in intragroup variation, it might not perform as well in maintaining biological relationships in certain datasets [21].

Selecting appropriate normalization methods is crucial for ensuring data quality and biological validity in untargeted metabolomics studies. The optimal approach depends on experimental design, analytical platform, and available resources. IS-based methods provide precise, metabolite-specific correction when appropriate standards are available. QC-based approaches effectively address temporal drift in large-scale studies. Model-based methods offer flexibility when additional standards or QCs are impractical. Utilizing evaluation frameworks like NOREVA enables objective comparison of normalization performance, while adherence to standardized protocols ensures reproducible and biologically meaningful results. As metabolomics continues to evolve with larger datasets and more complex experimental designs, proper implementation of these normalization strategies remains fundamental to extracting valid biological insights from mass spectrometry data.

FAQs: Addressing Common Annotation Challenges

FAQ 1: What are the different confidence levels for metabolite annotation, and how are they achieved?

The Metabolomics Standards Initiative (MSI) has established levels of confidence for metabolite identification to standardize reporting [27]. The following table outlines these levels.

Table: Metabolite Annotation Confidence Levels (MSI)

| Confidence Level | Description | Required Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1 (Confirmed Structure) | Identity confirmed with a reference standard. | Match on two orthogonal properties (e.g., RT and MS/MS spectrum) to an authentic standard analyzed in the same laboratory [28]. |

| Level 2 (Putative Annotation) | Specific compound class or candidate structure is proposed. | Spectral match to a reference library (MS/MS or MS) without RT confirmation, or evidence from in silico analysis [27]. |

| Level 3 (Putative Characteristic Class) | Assignment to a compound class. | Characteristic structural features inferred from spectral data (e.g., lipid class) [27]. |

| Level 4 (Unknown) | Unidentified or unannotated metabolite. | Can only be distinguished from background by analytical software, often solely by mass [27]. |

FAQ 2: Why do annotations vary so much between different laboratories or software pipelines?

A 2025 multi-laboratory study highlighted that annotation performance varies significantly due to several factors [18]. In the analysis of a standardized plant extract, individual teams identified only between 24% and 57% of the total 142 analytes detected collectively. The key sources of this variability include:

- Differences in Feature Detection and Grouping: In-source fragmentation and the formation of different adducts can create redundant features. If not properly grouped during data pre-processing, this can lead to inflated complexity and inconsistent annotation [18].

- Database Completeness and Selection: The scarcity of high-quality, curated MS/MS spectra for many compounds, especially plant secondary metabolites, in open-access repositories is a major bottleneck. Different teams use different databases, leading to different results [18].

- Over-estimation of Sample Complexity: There is a common temptation to interpret a high number of detected features as unique analytes. Many features actually stem from the same compound, and pipelines that fail to account for this will produce inconsistent annotations [18].

FAQ 3: My GC-MS data involves derivatized metabolites. How can in silico tools handle this?

Specialized workflows exist that use cheminformatics software to perform in silico derivatization of candidate structures. For example:

- Obtain Candidate Structures: Download potential structural isomers for a given formula from a database like PubChem [29].

- In silico Derivatization: Use software (e.g., ChemAxon Reactor) to programmatically add derivatization groups (e.g., trimethylsilyl (TMS) for GC-MS) to the candidate structures [29].

- Chemical Curation: Perform substructure searches to remove candidates that do not match the expected derivatization pattern (e.g., structures that still have free hydroxyl or carboxyl groups that should have been derivatized) [29].

- Retention Index (RI) Prediction: Use algorithms (e.g., the NIST group contribution method) to predict the RI of the derivatized candidates. A correction factor for the derivatization group (e.g., TMS) must be applied for accuracy [29].

- Spectral Matching: Finally, use MS prediction software (e.g., MassFrontier) to generate and compare fragmentation spectra of the curated, derivatized candidates against your experimental data [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Rate of False Positive Annotations

Solution: Implement a multi-layered filtering strategy that goes beyond simple spectral matching.

Table: Multi-layered Evidence for Annotation

| Layer of Evidence | Tool/Method Example | Function | Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accurate Mass & Formula | "Seven Golden Rules" | To obtain correct elemental formulas from accurate mass data, using isotope ratio information to constrain possibilities [29]. | 1. Acquire accurate mass data for molecular ion. 2. Use a constraint-based algorithm (e.g., "Seven Golden Rules") to generate candidate formulas, typically keeping the top 3 hits [29]. |

| Retention Time/Index | NIST RI Group Contribution Algorithm | To predict the chromatographic retention behavior of a candidate structure and filter out isomers with mismatched predicted vs. experimental retention [29]. | 1. Determine experimental Kovats Retention Index (RI). 2. For candidate structures, predict RI using a group contribution algorithm. 3. For derivatized compounds, apply a correction factor for the derivatization group. 4. Filter candidates based on the match between predicted and experimental RI [29]. |

| Fragmentation Spectrum | MassFrontier / SIRIUS / MetFrag | To predict in silico fragmentation spectra of candidate structures and score them against the experimental MS/MS spectrum [29] [27]. | 1. Acquire experimental MS/MS spectrum. 2. For candidate structures, generate in silico fragmentation spectra using software. 3. Score predicted spectra against experimental data. 4. Use a mass error window (e.g., 10 ppm for fragments) to determine matches [29]. |

| Database Consensus | MAW Workflow / GNPS | To combine results from multiple spectral and compound databases, improving candidate ranking and selection [27]. | 1. Perform spectral matching against multiple databases (e.g., GNPS, HMDB, MassBank). 2. Use a workflow (e.g., MAW) to integrate scores and rank candidates. 3. Apply a consensus approach to select the most likely candidate [27]. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates how these layers of evidence can be integrated into a robust annotation pipeline.

Problem: Technical and Biological Variation is Obscuring Biological Results in My Untargeted Dataset

Solution: Apply a rigorous data normalization method chosen for your experimental design. Different methods are suited for different types of unwanted variation [19].

Table: Common Data Normalization Methods in Metabolomics

| Normalization Method | Type | Best For | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Control-Based (e.g., LOWESS, SVR) | QC-based | Removing technical variation (instrumental drift, batch effects) in controlled experiments [19]. | Requires analysis of a pooled QC sample throughout the analytical run. Provides the highest technical precision [19]. |

| Model-Based (e.g., EigenMS, PQN) | Statistical/model-based | Epidemiological or complex studies where removing both technical variation and confounding biological biases is necessary [19]. | Can minimize biological biases (e.g., age, BMI) that may confound the biological variation of interest [19]. |

| Internal Standard-Based (e.g., CRMN) | IS-based | Targeted analysis. Can be used in untargeted GC-MS, but coverage of all metabolite classes is limited [19]. | Limited by the number and chemical diversity of the added internal standards. May not effectively normalize all metabolites in an untargeted study [19]. |

The following diagram outlines the decision process for selecting an appropriate normalization strategy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Reagents and Software for Advanced Annotation Pipelines

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| MSTFA (N-Methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide) | A common derivatization reagent for GC-MS that replaces active hydrogens in functional groups (e.g., -OH, -COOH, -NH) with trimethylsilyl groups, increasing volatility [29]. |

| Deuterated or 13C-Labeled Internal Standards | Used for quality control and specific normalization methods to monitor and correct for technical variability during sample preparation and analysis [19]. |

| Pooled QC Sample | A quality control sample created by combining small aliquots of all study samples. Analyzed intermittently throughout the batch run to monitor system stability and for QC-based normalization [19]. |

| ChemAxon Software (Standardizer, Reactor) | Cheminformatics tools used for standardizing chemical structures and performing in silico derivatization to model how candidate metabolites would react with derivatizing agents [29]. |

| SIRIUS Software | An annotation tool that combines isotope pattern analysis (CSI:FingerID) with MS/MS fragmentation trees to rank candidate structures and predict molecular formulas [27]. |

| NIST MS Software & RI Database | Provides a group contribution algorithm to predict Kovats Retention Indices (RI) for candidate structures, a critical filter for ruling out incorrect isomers [29]. |

| MAW (Metabolome Annotation Workflow) | An automated, reproducible workflow that integrates several tools and databases for metabolite annotation, compliant with FAIR principles [27]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Workflow Design & Strategy

Q1: Why is a combined univariate and multivariate approach recommended in untargeted metabolomics? A combined approach leverages the complementary strengths of both methods to overcome their individual limitations and provide a more robust biological interpretation [30] [31].

- Univariate Analysis examines one variable (metabolite) at a time. It is easy to use and interpret, using statistical tests like the Student's t-test and ANOVA to find metabolites with significant abundance changes between groups [30]. However, it ignores interactions between metabolites, increasing the risk of false positives or negatives [30].

- Multivariate Analysis examines all variables simultaneously. It identifies underlying patterns and relationships between metabolites [30].

- Unsupervised methods (e.g., Principal Component Analysis (PCA)) explore data structure without using sample class labels, helping to identify major trends, detect outliers, and assess batch effects [30] [31].

- Supervised methods (e.g., PLS-DA) use sample labels to identify features most associated with a specific phenotype and are often used to build predictive models [30].

Using multivariate analysis first provides a high-level overview of data quality and group separation. Following with univariate analysis on specific metabolites highlighted by the multivariate model then provides statistically validated, biologically relevant findings [30].

Q2: What is the logical sequence for applying these statistical methods? A recommended, iterative workflow is outlined in the diagram below. It begins with data preprocessing and quality control, followed by multivariate analysis for pattern discovery, and then univariate analysis for statistical validation.

Troubleshooting Common Scenarios

Q3: My PCA plot shows no clear separation between experimental groups. What should I do next? A lack of separation in PCA does not necessarily mean there are no biological differences. You should:

- Proceed with Supervised Multivariate Analysis: Apply methods like PLS-DA or Orthogonal PLS-DA (OPLS-DA), which are designed to maximize the separation between known classes [32]. These models can reveal subtle differences that PCA might miss.

- Conduct Univariate Analysis: Perform a careful univariate analysis. Even without strong group patterns, individual metabolites might show significant changes. Using multiple testing corrections (e.g., False Discovery Rate) is crucial here [32].

- Re-check Data Quality: Investigate your raw data and quality control (QC) samples. High variability within groups can obscure separation. Ensure proper normalization has been applied to reduce technical noise [9].

Q4: My multivariate model (e.g., PLS-DA) shows clear separation, but univariate tests on top VIP metabolites are not significant. Why? This discrepancy often arises from the different objectives of each method.

- Multivariate models like PLS-DA identify metabolites that, in combination, provide the best group separation. A metabolite with a high Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) score is crucial to the multivariate model but might not have a large fold change or low p-value on its own [30].

- Univariate tests evaluate each metabolite independently. A metabolite's abundance might be highly correlated with others in the pathway, so its individual variation appears less significant.

Solution: Do not rely solely on p-values. Integrate the results by creating a shortlist of candidates that have both high VIP scores (e.g., >1.5) and reasonably significant p-values (e.g., <0.05) or large fold changes. This integrated approach prioritizes metabolites that are important to the systemic model and statistically reliable [30].

Q5: How can I confidently identify metabolites that differentiate my experimental groups? Confident identification is a major bottleneck. The process should follow tiered levels of confidence, as summarized in the table below [9].

Table: Metabolite Identification Confidence Levels based on the Metabolomics Standards Initiative (MSI)

| Level | Identification Confidence | Required Evidence | Typical Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identified Compound | Comparison to authentic standard using two independent data points (e.g., RT and MS/MS spectrum) [30] | LC/GC-MS with in-house library |

| 2 | Putatively Annotated Compound | Evidence from physical/chemical properties vs. library data (e.g., accurate mass, MS/MS) [30] [9] | Accurate mass HRAM MS vs. METLIN, mzCloud [30] |

| 3 | Putatively Characterized Compound Class | Evidence by physicochemical properties of a compound class (e.g., lipid class) | Accurate mass, isotope pattern |

| 4 | Unknown Compound | Can be detected but cannot be characterized | N/A |

For untargeted discovery, Level 2 is often the goal. To achieve this:

- Use High-Resolution Accurate Mass (HRAM) spectrometry to determine the empirical formula [30] [33].

- Perform MS/MS fragmentation and compare the spectrum against public databases (e.g., METLIN, mzCloud) [30] [34].

- Where possible, match the retention time to an authentic standard for the highest confidence (Level 1) [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Software for the Combined Analysis Workflow

| Item Name | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| QC Samples | Pooled quality control samples are used to monitor instrument stability, balance analytical bias, and filter out metabolite features with unacceptably high variance during data processing [9]. |

| Authentic Chemical Standards | Pure compounds used to confirm metabolite identity by matching both retention time and MS/MS spectrum, achieving Level 1 identification [9]. |

| METLIN / mzCloud Databases | Public MS and MS/MS spectral libraries used for putative annotation (Level 2) by comparing accurate mass and fragmentation patterns from experimental data [30]. |

| XCMS / MZmine / MS-DIAL | Open-source software packages for preprocessing raw mass spectrometry data. They perform critical steps like peak picking, alignment, and retention time correction [9]. |

| MetaboAnalyst | A comprehensive web-based platform that supports the entire statistical workflow, including PCA, PLS-DA, univariate tests (t-test, ANOVA), and pathway analysis [32]. |

| In-house Spectral Library | A custom, curated library of MS/MS spectra and retention times for metabolites relevant to your specific research area, built using authentic standards to enable high-confidence identification [30]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Heatmaps

Q1: Why does my heatmap have low page views or missing click data?

This common issue in web analytics heatmaps can stem from several sources. First, verify that your tracking code is correctly installed on all pages related to your project. If you've recently updated your website design, ensure the code remains intact. After installation, allow at least 30 minutes for the system to begin generating heatmap data. Always check your applied filters; clear all filters or adjust the time frame to "Today" to view the most recent data. If the problem persists, confirm that you are targeting the correct URL [35].

Q2: Why does my heatmap show a message 'This element is not visible on this page'?

This message indicates that the click data is based on the most frequently clicked elements across user sessions, but the specific recording you are viewing does not contain that particular element. The click data is aggregated from multiple user recordings, and this discrepancy is normal [35].

Q3: Why does my website appear with no CSS styling or old styling in the heatmaps?

This occurs when the tool cannot access your site's styling assets (CSS, fonts). Ensure your CSS files are deployed on a public server and are not blocked by IP, geolocation, or domain restrictions. The platform often caches styles upon first view. If you update your stylesheet, you may need to request a cache clearance, as the tool does not automatically handle resource versioning [35].

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

Q4: What should I do if my PCA analysis fails to generate a plot or throws an error?

Errors during PCA generation, especially with specific plot types, can often be traced to data formatting or software version issues. As one case shows, an error when using the "Symbols" flavour in an R package (stylo) was linked to the handling of text labels, even when other plot types worked fine. Ensure your data matrix is clean, check for any special characters, and confirm that you are using a compatible and up-to-date version of your analysis software (e.g., R) and the specific packages [36].

Q5: How do I decide the number of principal components (k) to keep for analysis?

The number of components is typically chosen by examining the percentage of variance explained by each principal component. You should calculate the eigenvalues from the covariance matrix, as each eigenvalue represents the amount of variance captured by its corresponding component. A common approach is to select the top k components that together explain a sufficiently high percentage (e.g., 95%) of the total variance in the dataset. This is visualized using a scree plot [37] [38].

Volcano Plots

Q6: What are the standard thresholds for defining significant features on a volcano plot?

Common thresholds combine both effect size and statistical significance. A typical starting point is an absolute log₂ fold change (|log₂FC|) greater than or equal to 1 (indicating a 2-fold change) and a q-value (FDR-adjusted p-value) of less than 0.05. These cut-offs should be pre-defined in your analysis plan and adjusted based on your study's goals, sample size, and biological context [39].

Q7: My volcano plot seems biased by outliers. How can I make it more robust?

Standard volcano plots, which rely on t-tests and fold-change calculations, can be sensitive to outliers. To address this, you can implement a robust volcano plot that uses kernel-weighted averages and variances instead of classical means and variances. This method assigns smaller weights to outlying observations, reducing their influence on the final results and leading to more reliable identification of differential features [40].

Q8: What are the common pitfalls to avoid when creating and interpreting volcano plots?

Several issues can compromise your volcano plot [39]:

- Small Sample Sizes: These can inflate variance and destabilize p-value and q-value estimates.

- Inadequate Normalization: Unaddressed batch effects can distort both fold-change and significance measures.

- Imputation Choices: The method used for handling missing values can bias log₂FC calculations.

- Threshold Hacking: Altering statistical cut-offs after looking at the data to include "favorite" features undermines reproducibility.

- Over-reliance on P-values: Always consider the biological relevance and effect size of a feature, not just its statistical significance.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Creating an Outlier-Robust Volcano Plot

This protocol is designed for identifying differential metabolites from noisy metabolomics datasets in the presence of outliers [40].

- Data Matrix Preparation: Let ( X = (x{ij}) ) be your metabolomics data matrix with ( p ) metabolites (rows) and ( n ) samples (columns). The first ( g1 ) columns represent the control group, and the remaining ( n - g_1 ) columns represent the disease group.

- Kernel-Weighted Statistics: For each metabolite ( i ), calculate a kernel-weighted average and variance for both the control and disease groups, instead of using the classical mean and variance. This involves assigning weights to each sample based on its proximity to the data distribution, thereby reducing the influence of outliers.

- Compute Robust Metrics: Use the kernel-weighted statistics to compute a robust t-statistic (and its corresponding p-value) and a robust fold-change value for each metabolite.

- Plot Generation: Create the volcano plot by plotting ( \log2(\text{Robust Fold Change}i) ) on the X-axis and ( -\log{10}(\text{p-value}i) ) from the robust t-test on the Y-axis for each metabolite.