Optimizing Microbial Cell Factories: Systems Metabolic Engineering for Next-Generation Biomanufacturing

This article provides a comprehensive overview of systems metabolic engineering strategies for developing high-performance microbial cell factories.

Optimizing Microbial Cell Factories: Systems Metabolic Engineering for Next-Generation Biomanufacturing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of systems metabolic engineering strategies for developing high-performance microbial cell factories. It covers foundational principles from host selection to pathway reconstruction, details advanced methodological tools including CRISPR and dynamic regulation, and addresses critical troubleshooting aspects like metabolic flux optimization and strain robustness. By synthesizing validation frameworks and comparative host analyses, this resource offers researchers and drug development professionals a structured guide to streamline the design and scaling of efficient microbial platforms for sustainable production of pharmaceuticals, chemicals, and materials.

Foundations of Systems Metabolic Engineering: From Principles to Host Selection

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is Systems Metabolic Engineering? Systems Metabolic Engineering is an advanced interdisciplinary field that integrates the principles and tools of systems biology, synthetic biology, and traditional metabolic engineering to systematically design and optimize microbial cell factories for the overproduction of valuable chemicals and materials [1] [2]. It enables the engineering of microorganisms on a systemic level, far beyond their native capabilities, by leveraging high-throughput omics data, computational modeling, and advanced genetic manipulation tools [1] [3].

2. What are the primary goals of Systems Metabolic Engineering? The main objectives are to:

- Develop high-performance microbial strains for the sustainable production of biofuels, pharmaceuticals, polymers, and chemicals [1] [4].

- Achieve industrial-level production standards, often characterized by high titers (e.g., >100 g/L), productivity (e.g., 3-4 g/L/h), and yield [1].

- Convert renewable, non-food biomass or even one-carbon substrates like CO2 into desired products, supporting a circular bioeconomy [1] [4].

3. How do I select the most suitable microbial host for my target chemical? Host selection is critical and should be based on multiple criteria, including:

- Innate Metabolic Capacity: The host's native pathways and precursors for the target chemical. Use Genome-scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) to calculate theoretical yields [2].

- Tolerance: The host's resilience to potential product or intermediate toxicity [5] [6].

- Genetic Toolbox: The availability of well-developed genetic tools for engineering the strain [1] [2].

- Safety: The organism's classification as Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) for certain applications [6].

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of common industrial workhorses [2]:

| Host Organism | Typical Products | Key Advantages | Common Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Alcohols, hydrocarbons, amino acids, polymer precursors [1] | Rapid growth, well-characterized genetics, extensive engineering tools [1] [6] | Acid production in high-cell-density cultures, lower native tolerance to some products [1] [6] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Ethanol, organic acids, natural products, recombinant proteins [6] | GRAS status, high acid/oxidative stress tolerance, eukaryotic protein processing [6] | Often requires more complex pathway engineering for non-native products [2] |

| Corynebacterium glutamicum | Amino acids (L-lysine, L-glutamate), organic acids [6] [2] | Industrial-scale amino acid production, robust secretion capabilities [6] | Less developed genetic tools compared to E. coli and yeast [6] |

| Bacillus subtilis | Enzymes, biopolymers [6] | Efficient protein secretion, GRAS status [6] | - |

| Pseudomonas putida | Aromatics, difficult-to-secrete compounds [6] | Versatile metabolism, high solvent tolerance [6] | - |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Product Titer or Yield

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Inefficient or Suboptimal Metabolic Pathway

- Solution: Reconstruct the biosynthetic pathway.

- Design Novel Pathways: Use computational de novo pathway builders to identify heterologous or artificial pathways not present in the native host [6].

- Engineer Key Enzymes: Improve catalytic efficiency or substrate specificity of bottleneck enzymes via protein engineering. Computational tools like docking and molecular dynamics (MD) can guide rational design [6].

- Cofactor Engineering: Balance cofactor availability (e.g., NADPH/NADH) by switching enzyme cofactor specificity or introducing transhydrogenases to enhance flux [2].

- Solution: Reconstruct the biosynthetic pathway.

Cause 2: Insufficient Metabolic Flux Toward the Product

- Solution: Perform metabolic flux optimization using computational and experimental methods.

- Use Flux Balance Analysis (FBA): Apply FBA with Genome-scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) to predict flux distributions and identify gene knockout or up/down-regulation targets that maximize product yield [2] [7].

- Implement Strain Design Algorithms: Utilize algorithms like OptORF, a bilevel mixed integer linear programming (MILP) method, to predict optimal gene deletions that couple growth with high chemical production [7].

- Dynamic Regulation: Implement synthetic genetic circuits (e.g., metabolite-responsive promoters) to dynamically regulate pathway expression, avoiding buildup of intermediate metabolites and balancing growth with production [5] [3].

- Solution: Perform metabolic flux optimization using computational and experimental methods.

Cause 3: Inadequate Host Selection

- Solution: Quantitatively evaluate and select the best host.

- Compare the Maximum Theoretical Yield (YТ) and Maximum Achievable Yield (YА) of your target chemical across different hosts using GEMs. YА accounts for energy used for growth and maintenance, providing a more realistic metric [2].

- For example, for L-lysine production from glucose, S. cerevisiae shows a higher YT (0.857 mol/mol) than E. coli (0.799 mol/mol), guiding host selection [2].

- Solution: Quantitatively evaluate and select the best host.

Problem: Impaired Cell Growth or Viability

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Metabolic Burden

- Solution: Reduce the resource load from heterologous expression.

- Use Genomic Integration: Integrate pathway genes into the chromosome instead of using high-copy-number plasmids to reduce the energetic cost of replication and expression [5].

- Fine-tune Expression: Utilize synthetic promoter and RBS (Ribosome Binding Site) libraries to optimize, rather than maximize, the expression levels of each pathway enzyme [5] [3].

- Divide Labor: In co-culture systems, distribute different parts of the metabolic pathway across specialized strains to lessen the burden on a single strain [5].

- Solution: Reduce the resource load from heterologous expression.

Cause 2: Toxicity of Product or Metabolic Intermediates

- Solution: Enhance cellular tolerance.

- Transporter Engineering: Overexpress efflux transporters to actively secrete the toxic product from the cell, reducing intracellular accumulation [5].

- Global Regulator Engineering: Use techniques like global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME) to reprogram cellular transcription and evoke complex, multigenic tolerance phenotypes [1] [5].

- Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE): Subject the engineered strain to long-term cultivation under selective pressure (e.g., high product concentration) to evolve and select for more robust mutants [5].

- Solution: Enhance cellular tolerance.

Cause 3: Byproduct Formation

- Solution: Eliminate competing pathways.

- Gene Deletion: Use CRISPR-Cas9 or recombineering to delete genes responsible for major byproduct formation. For example, deleting the pflB gene (pyruvate formate-lyase) in E. coli can prevent unwanted formate production and redirect flux [4].

- Suppress Carbon Overflow: Engineer central metabolism (e.g., reduce acetic acid formation in E. coli) to improve carbon efficiency and allow for high-cell-density cultivations [1].

- Solution: Eliminate competing pathways.

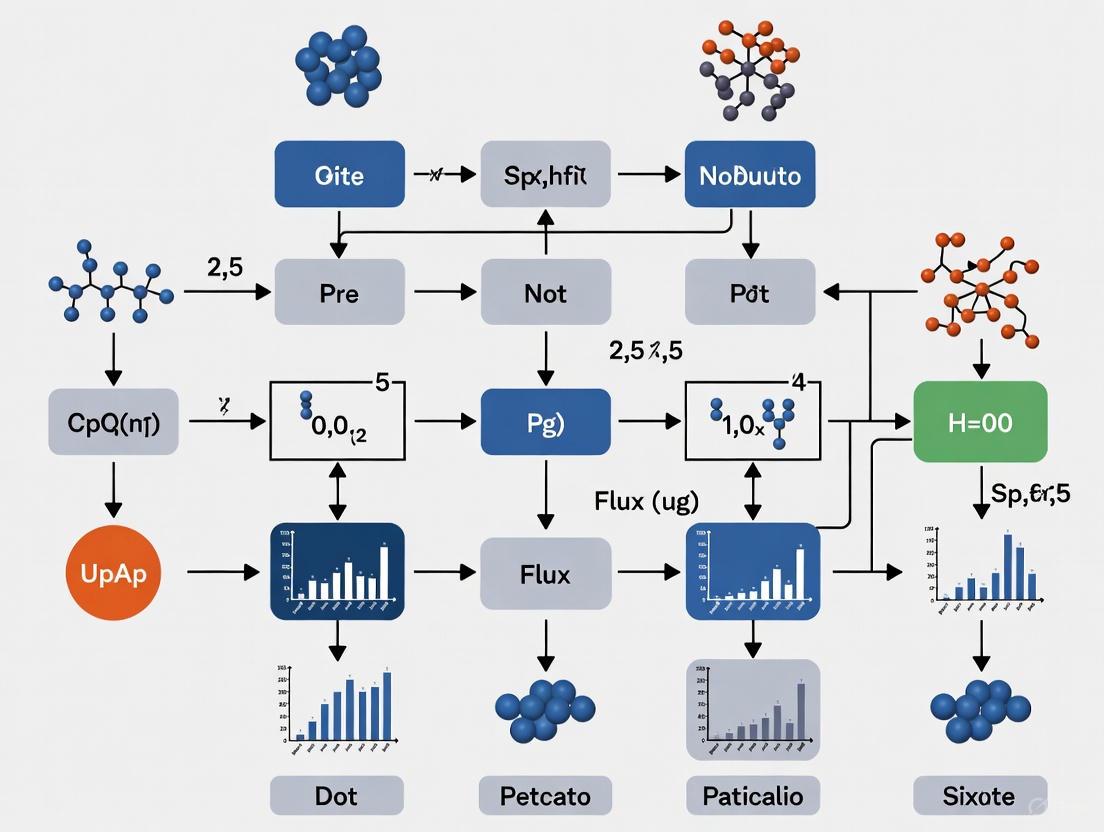

The following diagram illustrates a consolidated experimental workflow for developing a microbial cell factory, integrating the troubleshooting strategies above.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing CRISPR-Cas9 for Gene Knockout in E. coli

Purpose: To precisely delete a target gene to eliminate a competing metabolic reaction.

Materials:

- Plasmid System: A CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid expressing both the Cas9 nuclease and a designed guide RNA (gRNA) targeting the gene of interest.

- Repair Template: A single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) or double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) containing homology arms (~40-50 bp) flanking the deletion site.

- Host Strain: An engineered E. coli strain (e.g., with λ Red recombinase genes expressed from a helper plasmid to enhance recombination) [1] [8].

- Media: LB broth and agar plates with appropriate antibiotics.

Procedure:

- gRNA Design: Design a 20-nucleotide gRNA sequence that is specific to the genomic target site, ensuring it is unique to avoid off-target effects [8].

- Transformation: Co-transform the CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid and the repair template into the E. coli host strain.

- Selection and Screening: Plate the transformed cells on selective media. The Cas9-induced double-strand break is lethal unless repaired by homologous recombination using the supplied repair template, which results in the desired deletion.

- Curing the Plasmid: After confirming the gene deletion via colony PCR and/or sequencing, grow the positive colonies without antibiotic selection to cure the CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid.

- Validation: Sequence the modified genomic locus to confirm the precise deletion and absence of unintended mutations [8].

Protocol 2: Running Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) with a Genome-Scale Model

Purpose: To predict the maximum theoretical yield of a target chemical and identify optimal flux distributions.

Materials:

- Software: A constraint-based modeling environment (e.g., Cobrapy in Python, the COBRA Toolbox for MATLAB).

- Model: A curated Genome-scale Metabolic Model (GEM) for your host organism (e.g., E. coli iJR904 or iAF1260) [7].

- Constraints: Experimentally measured substrate uptake rates (e.g., glucose uptake rate).

Procedure:

- Model Loading: Load the GEM into your software environment. The model is represented by a stoichiometric matrix S, where S * v = 0 describes the steady-state mass balance for all metabolites [7].

- Apply Constraints: Set the lower and upper bounds for exchange reactions. For example, set the glucose uptake rate to a measured value and oxygen uptake rate based on aeration conditions.

- Define Objective Function: Typically, the biomass reaction is set as the objective to be maximized to simulate growth optimization [7].

- Solve the Linear Programming (LP) Problem: The solver finds a flux distribution v that maximizes the objective function (biomass, Z) subject to the constraints: Max Z, subject to S * v = 0 and lb ≤ v ≤ ub.

- Analyze Production Envelope: Use Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) to find the range of possible production rates for your target chemical at different growth rates, visualizing the trade-off between growth and production [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential tools and reagents for systems metabolic engineering projects.

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Example/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Model (GEM) | Mathematical representation of metabolism for in silico simulation and prediction of strain behavior [6] [2]. | iML1515 model for E. coli used to predict gene knockout targets for succinate overproduction [2]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | RNA-guided genome editing system for precise gene knockouts, knock-ins, and regulation [1] [8]. | Multiplexed editing of several genes in the DXP pathway to enhance lycopene production [9] [8]. |

| λ Red Recombineering System | Phage-derived proteins (Exo, Beta, Gam) that enable highly efficient homologous recombination with linear DNA in E. coli [1]. | One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes using PCR products with homologous extensions [1]. |

| Synthetic Promoter/RBS Library | A collection of well-characterized DNA parts to fine-tune the transcription and translation rates of pathway genes [3]. | Optimizing the expression levels of each enzyme in a heterologous mevalonate pathway to maximize flux and reduce burden [3]. |

| Flux Analysis Software (FBA/FVA) | Computational tools like Cobrapy to perform Flux Balance Analysis and Flux Variability Analysis on GEMs [7]. | Identifying essential genes and predicting maximum yields for a target chemical under different nutrient conditions [7]. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ: My microbial cell factory shows poor product yield despite high cell density. What is the cause and how can I fix it?

This is a classic symptom of the inherent competition between cellular growth and product synthesis. Cells allocate finite resources like carbon and energy to either multiply or manufacture your desired compound, rather than doing both optimally [10].

- Recommended Solution: Implement a dynamic control strategy to decouple growth and production phases. Program cells to first grow to a high density, then switch to a high-production mode. The most effective genetic circuits are those that, upon induction, actively inhibit the host's native metabolic enzymes responsible for growth. This strategic shutdown re-routes the cell's resources toward your target chemical [10].

FAQ: I suspect my bioreactor is contaminated. How can I confirm this and identify the source?

Early detection is key to minimizing losses. Contamination can manifest as unexpected culture turbidity, changes in color (e.g., phenol red medium turning yellow from pink due to acid formation), or unusual smells [11].

- Step-by-Step Diagnosis:

- Check the Inoculum: Re-plate a sample of your seed culture on a rich growth medium to check for hidden contaminants [11].

- Inspect Hardware: Thoroughly check all O-rings on vessels, ports, and sensors for damage or poor fit. Replace O-rings regularly (e.g., after 10-20 sterilization cycles) [11].

- Verify Sterilization: Confirm your autoclave reaches and maintains the correct temperature using test phials. Ensure steam can penetrate all items by avoiding over-packing [11].

- Test Methodologies: Perform a "blank run" by leaving uninoculated medium in the sterilized vessel under normal operating conditions to see if growth occurs [11].

FAQ: My biotransformation process is inefficient, with low chemical yields. How can I improve it?

Low yields in microbial biotransformation can stem from reactant or product toxicity, enzyme inhibition, or the high specificity of enzymes leading to slow reaction rates [12].

- Improvement Strategies:

- Consider Immobilization: Use enzyme or cell immobilization techniques to enhance stability and allow for catalyst reuse [12].

- Explore Genetic Engineering: Engineer microbes to improve enzyme tolerance to substrates, products, or organic solvents [13] [12].

- Optimize Reaction Conditions: Fine-tune parameters like temperature, pH, and feeding strategies to minimize inhibition and maximize conversion rates [12].

Quantitative Data and Design Principles

Key Performance Indicators in Microbial Metabolic Engineering

The table below summarizes critical parameters and their target optima for efficient bioproduction, based on recent research [10].

| Parameter | Typical Challenge | Optimal Strategy | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Rate vs. Synthesis Rate | Direct competition for cellular resources | Balance at a "medium-growth, medium-synthesis" point; avoid maximizing either. | Maximizes overall volumetric productivity in single-phase systems [10]. |

| Metabolic Burden | Resource diversion to maintain engineered pathways | Use dynamic control circuits that inhibit native metabolism during production phase. | Re-routes precursors and energy (ribosomes) from growth to product synthesis [10]. |

| Substrate Uptake | Limited transport into the cell | Universally boost expression of substrate transporter proteins. | Improves productivity irrespective of the control circuit used [10]. |

| Pathway Topology | Precursor depletion affecting other vital processes | For products from essential precursors (e.g., amino acids), repress production pathway during growth phase. | Preserves building blocks for growth, then allows high-yield production [10]. |

Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Engineering

This table lists essential materials and their specific functions in developing and optimizing microbial cell factories.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Viability Stains (e.g., Green/Red dye kits) | Cell-permeant green stain labels all cells; cell-impermeant red stain identifies cells with compromised membranes (dead cells) [14]. |

| Lysozyme | Enzyme used to enhance the lysis of bacterial cell walls, particularly for efficient protein extraction [14]. |

| B-PER Reagent | A ready-to-use reagent for lysing bacterial cells, effective for E. coli and other gram-negative bacteria [14]. |

| Glycerol | Used at 15% concentration for preparing frozen stock cultures of microbes (e.g., yeast) for long-term storage at -80°C [14]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | RNA-guided genome editing tool for precise genetic modifications, pathway optimization, and creating regulatory systems in microbial hosts [8]. |

Core Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Implementing a Dynamic Metabolic Switch

This protocol outlines the steps to engineer a two-phase dynamic control system for decoupling growth and production, based on current best practices [10].

- Circuit Design: Design a genetic circuit where a target metabolic pathway is under the control of an inducible promoter. For optimal performance, the circuit should, upon induction, also express inhibitors for key native metabolic enzymes involved in growth.

- Strain Transformation: Introduce the constructed genetic circuit into your microbial host (e.g., E. coli or S. cerevisiae). Validate the integration and functionality using colony PCR and sequencing.

- Two-Phase Bioreactor Cultivation:

- Growth Phase: Incubate the culture under conditions that suppress the inducer, allowing the cells to multiply and achieve high density.

- Production Phase: Once a desired optical density is reached, add the inducer (e.g., IPTG or anhydrotetracycline) to activate the circuit. This switches the cellular resources from growth to chemical production.

- Monitoring and Analysis: Regularly sample the culture to measure cell density (OD600), substrate consumption, and product formation (e.g., via HPLC or GC-MS) to track the switch's efficiency.

Core Workflow for Microbial Catalyst Development

The diagram below outlines the overarching research and development cycle for creating and optimizing a microbial cell factory, integrating metabolic engineering and troubleshooting.

Advanced Strategy: Metabolic Engineering Design Principles

The field is moving away from intuition-based trial-and-error toward predictive, rational design. A "host-aware" multi-scale model that integrates cell-level dynamics (metabolism, resource competition) with population-level behavior in a batch culture reveals key principles [10]:

- The Myth of Maximization: The highest volumetric productivity is not achieved at maximum growth or maximum synthesis rates. The optimum lies at a carefully balanced "medium-growth, medium-synthesis" point [10].

- The Power of Inhibition: Dynamic control is superior. The best-performing circuits are those that, upon induction, actively inhibit the host's native metabolic enzymes. This forces a re-routing of resources from growth to production [10].

- Context-Dependent Topology: The optimal circuit design depends on your product. If it is synthesized from precursors that are also essential for cell growth (e.g., amino acids), the best strategy is to repress the production pathway during the growth phase to preserve those vital building blocks [10].

Within metabolic engineering, selecting the optimal microbial host strain is a critical first step in developing an efficient cell factory. This decision fundamentally shapes the project's trajectory, influencing the genetic engineering strategy, fermentation process, and ultimate economic viability. The core dilemma often involves choosing between well-characterized model organisms and specialized natural overproducers. Model organisms offer extensive genetic toolkits and deep fundamental knowledge, while natural overproducers provide innate, high-yielding metabolic pathways. This guide provides troubleshooting and FAQs to help researchers navigate this complex selection process, framed within the context of optimizing microbial cell factories.

Core Concepts and Strategic Comparison

The table below outlines the primary strategic considerations when choosing a host strain.

| Criterion | Model Organisms (e.g., E. coli, S. cerevisiae) | Natural Overproducers (e.g., A. succinogenes, A. niger) |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Tractability | Extensive genetic tools available (e.g., CRISPR, standardized plasmids); easy to manipulate [15] [16]. | Often limited genetic tools; can be difficult and time-consuming to engineer [15]. |

| Metabolic Capacity | May require extensive engineering to introduce or enhance pathways; metabolic capacity can be computed in silico [2] [17]. | Possess innate, high-flux pathways for target compounds; often have high tolerance to the product [15] [17]. |

| Knowledge Base | Vast amount of published 'omics data, known physiology, and established protocols [18] [19]. | Physiological and genetic knowledge may be sparse, requiring initial characterization [15]. |

| Industrial Robustness | May require engineering for process stability, substrate range, or toxin tolerance [17]. | Often naturally robust in their preferred fermentation conditions [15]. |

| Regulatory Status | Some have Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) status, which is advantageous for food/pharma applications [2]. | Status may be unknown or not GRAS, potentially complicating product approval [15]. |

Quantitative Comparison of Metabolic Capacities

Theoretical and achievable yields are key metrics for selection. The following table compares the metabolic capacities of five common industrial microorganisms for producing example chemicals from glucose under aerobic conditions, as calculated from genome-scale metabolic models [2].

| Target Chemical | Host Strain | Maximum Theoretical Yield (mol/mol glucose) | Maximum Achievable Yield (mol/mol glucose) |

|---|---|---|---|

| L-Lysine | S. cerevisiae | 0.8571 | Data not provided in source |

| B. subtilis | 0.8214 | Data not provided in source | |

| C. glutamicum | 0.8098 | Data not provided in source | |

| E. coli | 0.7985 | Data not provided in source | |

| P. putida | 0.7680 | Data not provided in source | |

| Succinic Acid | Native producer (e.g., A. succinogenes) | Not specified | ~150 g/L (fermentation titer) [17] |

| Engineered E. coli | Not specified | ~100 g/L (fermentation titer) [17] |

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Workflow for Host Strain Selection and Evaluation

The following diagram outlines a systematic workflow for selecting and evaluating a host strain.

Detailed Methodologies

1. Computational Prediction of Metabolic Capacity using GEMs

- Objective: To quantitatively predict the potential of different microbial strains to produce a target chemical using Genome-scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) [2].

- Procedure:

- Model Selection: Obtain curated GEMs for candidate host strains (e.g., B. subtilis, C. glutamicum, E. coli, P. putida, S. cerevisiae).

- Pathway Reconstruction: If the biosynthetic pathway is non-native, add the necessary heterologous reactions to the model. Ensure all reactions are mass and charge-balanced.

- Constraint Definition: Set constraints to reflect the planned cultivation conditions:

- Carbon source uptake rate (e.g., glucose).

- Oxygen uptake rate (aerobic, microaerobic, anaerobic).

- Non-growth-associated maintenance (NGAM) energy.

- Lower bound for growth rate (e.g., 10% of maximum).

- Yield Calculation:

- Maximum Theoretical Yield (YT): Formulate the model to maximize the production rate of the target chemical, ignoring maintenance and growth demands.

- Maximum Achievable Yield (YA): Formulate the model to maximize chemical production while accounting for NGAM and a minimum growth constraint.

- Analysis: Compare YT and YA across all candidate strains to identify the most promising host.

2. Leveraging Natural Variation with MESSI

- Objective: To identify the best natural strain of S. cerevisiae for a product and find potential genetic engineering targets by analyzing natural variation [20].

- Procedure:

- Input: Provide the KEGG ID of the target metabolite or pathway of interest to the MESSI web server.

- Pathway Activity Calculation: The server uses the Pathway Activity Profiling (PAPi) algorithm on public metabolomic data from multiple yeast strains to calculate activity scores for metabolic pathways.

- Strain Ranking: MESSI aggregates pathway activity scores based on user-defined parameters (pathway weight and expectation) and outputs a ranked list of S. cerevisiae strains.

- Target Identification: The tool performs a genome-wide association study (GWAS) between metabolic pathway activities and genomic variants (SNPs, InDels), prioritizing genes and variants as potential metabolic engineering targets.

3. Fermentation Protocol for Evaluating Engineered Strains

- Objective: To experimentally validate the performance of selected or engineered strains in bioreactors [17].

- Procedure:

- Medium Preparation: Use a defined or complex medium with the primary carbon source (e.g., glucose, glycerol, molasses). Antibiotics may be added if required to maintain plasmid stability.

- Inoculum Preparation: Grow a seed culture from a single colony in a shake flask overnight.

- Bioreactor Setup:

- Transfer the inoculum to a bioreactor with controlled temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen.

- For fed-batch fermentation, begin with a batch phase and initiate a controlled feed of carbon source once it is depleted.

- Process Monitoring: Regularly sample the fermentation broth to measure:

- Cell Density (OD600).

- Substrate Concentration (e.g., glucose).

- Product Titer (HPLC, GC).

- By-product Formation.

- Data Analysis: Calculate key performance metrics: final titer (g/L), yield (g product/g substrate), and productivity (g/L/h).

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Low Titer or Yield in Fermentation

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Titer | Metabolic burden from heterologous pathway expression. | Use genomic integration instead of plasmids; fine-tune promoter strength to balance expression [15]. |

| Toxicity of the target product to the host cells. | Engineer host for higher tolerance (adaptive laboratory evolution); implement continuous product removal [17]. | |

| Inefficient product secretion leading to feedback inhibition. | Overexpress or engineer specific transporters to enhance efflux [17]. | |

| Low Yield | Competition for precursors and energy from native metabolism. | Knock out competing pathways for by-products (e.g., acetate, lactate) [17]. |

| Imbalance in cofactors (NAD(P)H, ATP). | Employ cofactor engineering to regenerate and balance cofactor pools [17]. | |

| Inefficient metabolic flux through the engineered pathway. | Use dynamic regulatory systems to rewire flux; optimize codon usage of heterologous genes [15] [17]. |

Strain Construction and Selection Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Genetic Manipulation | Lack of efficient genetic tools for non-model organisms. | Develop electroporation protocols; adapt tools from related species; use broad-host-range vectors [15]. |

| Codon Bias | Heterologous genes contain codons rare in the host, causing translational errors. | Use gene synthesis to codon-optimize the entire pathway for the host [15]. |

| Genomic Instability | Engineered strains lose productivity over generations. | Remove unnecessary selection markers; avoid repetitive sequences; ensure genetic modifications are stable [21]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Should I always choose the strain with the highest predicted metabolic capacity?

Not necessarily. While high predicted yield is crucial, other factors are equally important. A strain like C. glutamicum is the industrial standard for L-glutamate production despite not always having the highest theoretical yield because of its proven performance, robustness, high tolerance, and well-established industrial processes [2].

When is a synthetic microbial consortium a better choice than a single strain?

A consortium is advantageous when the metabolic pathway is long and complex, as splitting it across multiple strains reduces the cellular burden on any single organism [15]. It is also beneficial when different strains can form a symbiotic relationship, such as one strain consuming another's by-product, leading to a more efficient overall process [15].

How can I prevent contamination during fermentation runs?

Implement strict aseptic techniques. Key measures include: regular cleaning and disinfection of incubators and workbenches; using sterile, filtered media and reagents; sourcing cell lines from reputable repositories; and conducting regular contamination checks using PCR, fluorescence staining, or culture methods [21]. If contamination occurs, treat with high concentrations of targeted antibiotics or physically remove contaminants.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) | In silico prediction of metabolic fluxes, yields, and identification of engineering targets [2]. | Calculating maximum theoretical and achievable yields for a target chemical across multiple host strains. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Precise genome editing for gene knockouts, knock-ins, and regulatory element engineering [2]. | Rapidly engineering a model organism like E. coli or S. cerevisiae to express a heterologous pathway. |

| Codon-Optimized Synthetic Genes | Genes synthesized with the host's preferred codons to ensure high-efficiency translation [15]. | Expressing a heterologous pathway from a plant or fungus in a bacterial host without translational stalling. |

| Specialized Expression Vectors | Plasmids designed for specific hosts, containing compatible origins of replication, promoters, and selection markers. | Constitutive or inducible expression of pathway genes in P. pastoris or C. glutamicum [15]. |

| Antibiotics and Selection Markers | Selective pressure to maintain plasmids or select for successful genomic integrations. | Maintaining an expression plasmid in E. coli using ampicillin or kanamycin resistance. |

| Defined and Complex Media | Support the growth and production of the microbial cell factory. | Using minimal media for fundamental yield studies or complex media like molasses for high-titer industrial fermentation [17]. |

Key Metabolic Pathways and Engineering Strategies

Central Pathways for Organic Acid Production

The diagram below illustrates the primary metabolic pathways involved in the production of key organic acids, highlighting major engineering targets.

| Target Organic Acid | Preferred Native Producer | Key Metabolic Engineering Strategies | Reported High Titer (Fed-Batch) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Citric Acid | Aspergillus niger | Enhance glycolytic and TCA flux; overexpress pyruvate carboxylase; reduce by-products [17]. | >180 g/L [17] |

| Succinic Acid | Mannheimia succiniciproducens, A. succinogenes | Use reductive TCA and glyoxylate pathways; overexpress phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase; balance NADH/NAD+ [17]. | ~150 g/L (native) [17] |

| Malic Acid | Aspergillus oryzae, R. oryzae | Overexpress pyruvate carboxylase and malate dehydrogenase; engineer malate transporter [15] [17]. | ~200 g/L (native) [17] |

Central carbon metabolism (CCM) represents the most fundamental metabolic process in living organisms, responsible for maintaining normal cellular growth and providing precursors for biosynthesis. In microbial cell factories, CCM includes glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, and the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), which collectively serve as the primary hub for carbon conversion and energy generation [22]. These pathways generate essential precursors, energy (ATP), and redox cofactors (NADH, NADPH) required for organic acid biosynthesis and other valuable compounds [22] [23].

Optimizing CCM has become a pivotal strategy in metabolic engineering for enhancing the production of organic acids and other valuable chemicals. By engineering these fundamental pathways, researchers can increase the supply of precursors for targeted compounds and rebalance energy and redox cofactor availability to promote output of final products [22]. Microbial cell factories such as Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae have been extensively engineered to optimize CCM for industrial production of various biochemicals [2] [24].

Key Pathways in Central Carbon Metabolism

Glycolysis

Glycolysis converts glucose into pyruvate, generating ATP, NADH, and metabolic intermediates. For organic acid production, glycolytic intermediates such as phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) and pyruvate serve as direct precursors for various organic acids including lactate, pyruvate, and oxaloacetate [22] [23].

Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle

The TCA cycle oxidizes acetyl-CoA derived from pyruvate to produce reducing equivalents (NADH, FADH2) and GTP, while generating carbon skeletons for biosynthesis. Several TCA cycle intermediates serve as direct precursors for organic acid production, including citrate, α-ketoglutarate, succinate, fumarate, and malate [22] [23].

Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP)

The PPP operates in parallel to glycolysis and serves two primary functions: generating NADPH for reductive biosynthesis and producing pentose phosphates for nucleotide synthesis. The NADPH produced is particularly crucial for fatty acid and amino acid biosynthesis [22]. The PPP also provides erythrose-4-phosphate (E4P), an essential precursor for aromatic amino acid synthesis [22].

Quantitative Analysis of Metabolic Capacities

Table 1: Maximum theoretical yields (YT) of representative organic acids from glucose in different microbial hosts

| Organic Acid | E. coli | S. cerevisiae | C. glutamicum | B. subtilis | P. putida |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Succinate | 1.12 g/g | 0.91 g/g | 1.05 g/g | 0.98 g/g | 0.87 g/g |

| Lactate | 1.00 g/g | 0.90 g/g | 0.95 g/g | 0.92 g/g | 0.85 g/g |

| Acetate | 0.67 g/g | 0.58 g/g | 0.63 g/g | 0.61 g/g | 0.55 g/g |

| 3-HP | 0.84 g/g | 0.79 g/g | 0.82 g/g | 0.80 g/g | 0.76 g/g |

| Citrate | 1.07 g/g | 1.02 g/g | 1.05 g/g | 1.03 g/g | 0.96 g/g |

Note: Yields represent grams of product per gram of glucose under aerobic conditions. Data compiled from genome-scale metabolic model simulations [2].

Table 2: Key precursors from CCM for organic acid biosynthesis

| Precursor | Source Pathway | Target Organic Acids | Key Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) | Glycolysis | Oxaloacetate, Succinate, Fumarate | PEP carboxylase, PEP carboxykinase |

| Pyruvate | Glycolysis | Lactate, Alanine, Oxaloacetate | Lactate dehydrogenase, Pyruvate carboxylase |

| Acetyl-CoA | Pyruvate dehydrogenase | Citrate, Acetate, Fatty acids | Pyruvate dehydrogenase, ACL |

| Oxaloacetate | TCA cycle | Aspartate, Glutamate, Succinate | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| α-Ketoglutarate | TCA cycle | Glutamate, Glutarate | Glutamate dehydrogenase |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ 1: Why is my organic acid yield lower than theoretically predicted despite pathway optimization?

Issue: Theoretical yields assume ideal conditions where all carbon flux is directed toward the target product. In practice, competing pathways, regulatory mechanisms, and cofactor imbalances often reduce actual yields.

Solutions:

- Eliminate competing pathways: Knock out genes encoding enzymes for byproduct formation. For example, delete lactate dehydrogenase (ldhA) in E. coli when producing succinate to prevent lactate accumulation [22] [25].

- Address redox imbalances: Insufficient NADPH supply often limits reductive biosynthesis. Introduce NADPH-generating enzymes such as glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (Zwf) or implement transhydrogenase cycles [22].

- Overcome allosteric regulation: Identify and modify feedback inhibition in key enzymes. Use enzyme variants insensitive to allosteric inhibitors for critical steps like phosphofructokinase in glycolysis [22] [25].

- Implement dynamic control: Use metabolite-responsive promoters to dynamically regulate pathway expression, avoiding metabolic burden during growth phases [22].

Experimental Protocol: Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)

- Obtain or reconstruct a genome-scale metabolic model for your production host [2] [26].

- Set the objective function to maximize biomass production for wild-type or product formation for engineered strains.

- Constrain the model with measured uptake and secretion rates.

- Identify flux distributions using constraint-based optimization.

- Perform flux variability analysis to identify alternative optimal solutions [26].

- Compare predicted versus measured fluxes to identify discrepancies and potential regulatory constraints [25].

FAQ 2: How can I resolve carbon flux distribution issues between biomass and product formation?

Issue: Microbial cells naturally optimize for growth rather than product formation, creating competition between biomass synthesis and target chemical production.

Solutions:

- Use growth-coupled production designs: Engineer strains where target product formation becomes essential for growth through careful gene knockouts [25].

- Implement two-stage fermentations: Separate growth phase from production phase using inducible expression systems [22].

- Modulate energy metabolism: Under carbon-rich conditions, cells may prioritize ATP production over yield. Modify ATP synthase activity or introduce ATP-consuming futile cycles to redirect metabolism [25].

- Apply adaptive laboratory evolution: Subject engineered strains to selective pressure for improved product yield, allowing natural evolution to optimize flux distribution [25].

Experimental Protocol: Metabolic Flux Analysis with Isotope Tracing

- Select an appropriate isotopic tracer (e.g., U-13C glucose, 1-13C glucose) based on the pathways of interest [27].

- Cultivate cells in minimal medium with the labeled substrate until metabolic steady state is reached.

- Quench metabolism rapidly using cold methanol or other quenching agents.

- Extract intracellular metabolites using appropriate solvent systems.

- Analyze metabolite labeling patterns using LC-MS or GC-MS [27].

- Calculate flux distributions using computational tools such as INCA or 13C-FLUX [28].

- Compare fluxes between reference and engineered strains to identify significant changes [28].

FAQ 3: What strategies can overcome precursor limitation in organic acid biosynthesis?

Issue: Insufficient supply of key precursors such as phosphoenolpyruvate, oxaloacetate, or acetyl-CoA often limits organic acid production.

Solutions:

- Introduce heterologous pathways: Implement non-native routes like the phosphoketolase (PHK) pathway to bypass native regulation and enhance precursor supply [22].

- Amplify precursor pools: Overexpress enzymes that replenish TCA cycle intermediates, such as pyruvate carboxylase or PEP carboxylase [22].

- Reduce precursor diversion: Downregulate competing pathways that consume target precursors using CRISPRi or antisense RNA [22] [24].

- Enh cofactor supply: Express NAD kinase or NADP-dependent glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase to increase NADPH availability for reductive biosynthesis [22].

Experimental Protocol: Introduction of Heterologous Phosphoketolase Pathway

- Select phosphoketolase (PK) and phosphotransacetylase (PTA) genes with high activity in your host organism (e.g., from Aspergillus nidulans for yeast) [22].

- Codon-optimize genes for your expression host and synthesize.

- Clone genes under appropriate promoters (constitutive or inducible) in expression vectors.

- Transform host strain and verify integration/expression.

- Characterize strain in controlled bioreactors with precise monitoring of substrate consumption and product formation.

- Analyze intracellular metabolite pools to verify increased acetyl-CoA levels.

- Use 13C tracing to confirm carbon flux through the new pathway [22] [27].

FAQ 4: How can I improve carbon efficiency and reduce byproduct formation?

Issue: Significant carbon loss occurs through byproduct formation (e.g., acetate, glycerol, CO2), reducing yield of target organic acids.

Solutions:

- Delete byproduct pathways: Knock out genes responsible for major byproducts (e.g., poxB, pta for acetate in E. coli) [22].

- Optimize culture conditions: Control oxygen supply to minimize overflow metabolism; use fed-batch with controlled feeding to avoid carbon excess [25].

- Engineer cofactor specificity: Switch NADH-dependent to NADPH-dependent enzymes or vice versa to balance cofactor supply and demand [22].

- Enhance carbon conservation: Implement synthetic CO2 fixation pathways or glyoxylate shunt activation to recapture lost carbon [22].

Visualization of Central Carbon Metabolism and Organic Acid Biosynthesis

Diagram 1: Central carbon metabolism network showing major pathways and organic acid production routes. Key nodes highlight strategic engineering targets for enhancing organic acid yields.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key research reagents for metabolic engineering of central carbon metabolism

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Examples/Specific Products |

|---|---|---|

| Isotopic Tracers | Metabolic flux analysis | U-13C glucose, 1-13C glucose, 13C-glutamine |

| Genome Editing Tools | Strain engineering | CRISPR-Cas9 systems, CRISPRi, SAGE recombinase |

| Analytical Instruments | Metabolite quantification | LC-MS, GC-MS, NMR spectroscopy |

| Enzyme Assay Kits | Enzyme activity measurement | Pyruvate kinase assay, Lactate dehydrogenase assay |

| Metabolic Modulators | Pathway regulation | Small molecule inhibitors/activators of key enzymes |

| Culture Media | Controlled cultivation | Defined minimal media, Carbon-limited media |

| Plasmid Systems | Heterologous expression | Inducible promoters (pTet, pBAD), Integration vectors |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Metabolic modeling | COBRA toolbox, OptFlux, 13C-FLUX |

Advanced Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Organic Acid Production

Heterologous Pathway Implementation

The introduction of non-native pathways has proven highly effective for optimizing carbon flux. The phosphoketolase (PHK) pathway, consisting of only phosphoketolase (PK) and phosphotransacetylase (PTA), provides a shortcut for direct acetyl-CoA production from fructose-6-phosphate or xylulose-5-phosphate, bypassing multiple enzymatic steps in glycolysis [22]. This pathway has demonstrated remarkable success in enhancing production of acetyl-CoA-derived compounds:

- In Yarrowia lipolytica, PHK pathway expression increased total lipid production by 19% by correcting redox imbalance [22].

- In S. cerevisiae, the PHK pathway increased p-hydroxycinnamic acid yield to 12.5 g/L with a maximum yield on glucose of 154.9 mg/g [22].

- For 3-hydroxypropionic acid (3-HP) production, PHK pathway introduction increased yield by 41.9% while reducing glycerol byproduct by 48.1% [22].

Dynamic Metabolic Regulation

Static pathway optimization often fails to account for changing metabolic demands during different growth phases. Dynamic regulation strategies address this limitation by implementing feedback control systems that respond to metabolite levels [22]. For example, metabolite-responsive promoters can upreglate precursor supply pathways when intermediate pools are depleted, or downregulate competitive pathways when byproducts accumulate [22].

Cofactor Engineering

Optimizing cofactor availability represents a crucial aspect of CCM optimization. Native cofactor specificities often mismatch pathway requirements, creating redox imbalances that limit yields. Engineering solutions include:

- Switching cofactor specificity of key enzymes (e.g., NADH-dependent to NADPH-dependent)

- Introducing transhydrogenase cycles for interconversion between NADH and NADPH

- Expressing NAD kinase to enhance NADP+ supply [22]

For instance, the introduction of Deinococcus radiodurans response regulator DR1558 into E. coli improved NADPH generation from PPP and supplied cofactor requirements during PHB biosynthesis [22].

Future Perspectives

The continued advancement of CCM optimization for organic acid production will increasingly rely on multi-omics integration and machine learning approaches. Combining transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics datasets provides comprehensive views of metabolic regulation [29]. Meanwhile, genome-scale metabolic models continue to improve in predictive accuracy, enabling in silico design of optimal engineering strategies [2] [28].

The development of non-model organisms as specialized cell factories represents another promising direction. While E. coli and S. cerevisiae remain popular hosts, non-model organisms often possess native metabolic features advantageous for specific organic acid production [2] [24]. Advanced genome engineering tools are making these previously intractable organisms increasingly accessible for metabolic engineering applications.

As these technologies mature, the optimization of central carbon metabolism will continue to enhance microbial production of organic acids, driving advances in sustainable biomanufacturing and expanding the capabilities of microbial cell factories.

Troubleshooting Guide and FAQs for Microbial Cell Factory Optimization

This technical support center provides targeted solutions for common challenges encountered in the metabolic engineering lifecycle. The guidance is framed within the broader thesis that optimizing microbial cell factories requires a systematic, multi-disciplinary approach integrating metabolic engineering, synthetic biology, and fermentation technology to overcome biological and process constraints [30].

Host Selection and Engineering

FAQ: What are the key considerations when selecting a chassis organism for antibiotic production?

The ideal chassis organism depends on the complexity of your target molecule and its biosynthetic pathway. For complex natural products like antibiotics, actinomycetes (particularly Streptomyces species) are historically prolific producers and often contain native biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) [31]. For other valuable compounds such as nutraceuticals, the oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica is emerging as a powerful platform due to its high intrinsic flux toward acetyl-CoA, a key precursor for many value-added chemicals [32].

Table 1: Common Microbial Chassis and Their Engineering Applications

| Chassis Organism | Key Characteristics | Preferred Product Classes | Notable Engineering Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomyces albus | GC-rich genome; natural antibiotic producer; relatively small genome (6.8 Mbp) [31] | Antibiotics; secondary metabolites [31] | Deletion of 15 native BGCs to reduce metabolic competition and enhance heterologous production [31] |

| Escherichia coli | Well-characterized genetics; fast growth; extensive toolbox [33] | Chemicals, biofuels, polymers [33] | Engineering of replicative and chronological lifespan to enhance production of poly(lactate-co-3-hydroxybutyrate) and butyrate [33] |

| Yarrowia lipolytica | Oleaginous; high acetyl-CoA flux; GRAS status [32] | Nutraceuticals, lipids, terpenoids [32] | Compartmentalization of pathways in peroxisomes; engineering of acetyl-CoA supply [32] |

Troubleshooting Guide: My chosen host shows poor transformation or genetic instability.

- Problem: Low transformation efficiency, especially in non-model or GC-rich hosts.

- Solution: Utilize established chassis strains with better genetic characteristics. For example, Streptomyces lividans TK24 and S. albus J1074 are known for higher transformation efficiencies and genetic stability compared to other actinomycetes [31].

- Protocol: For actinomycetes, employ specialized techniques such as:

- Intergeneric Conjugation: Transfer DNA from E. coli to actinomycetes using a helper plasmid.

- PEG-Mediated Protoplast Transformation: Treat cells with lysozyme to create protoplasts, transform with DNA, and regenerate cell walls.

- Problem: Genetic instability after successful transformation.

- Solution: Ensure genetic elements (e.g., promoters, RBSs) are compatible with your host's system. For Yarrowia lipolytica, use codon-optimized genes and validated expression platforms [32].

Metabolic Pathway Optimization

FAQ: How can I increase the flux through a key metabolic precursor like acetyl-CoA?

Enhancing precursor supply is a cornerstone of metabolic engineering. The strategies vary by host organism.

Table 2: Strategies for Enhancing Key Metabolic Precursors

| Target Precursor | Host Organism | Engineering Strategy | Observed Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetyl-CoA | Yarrowia lipolytica | Engineered pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) by balancing subunit expression (Pda1, Pdb1, Lat1) [32] | Increased overall capacity of this key enzymatic complex |

| Acetyl-CoA | Yarrowia lipolytica | Introduced heterologous ATP citrate lyase pathway to convert citrate to cytosolic acetyl-CoA [32] | Provided an alternative route to generate cytosolic acetyl-CoA, bypassing the mitochondrial PDC |

| Acetyl-CoA | Yarrowia lipolytica | Enhanced β-oxidation pathway through coordinated overexpression of acyl-CoA oxidases and thiolases [32] | Increased conversion of fatty acids to acetyl-CoA units |

Troubleshooting Guide: My pathway is introduced, but product titer remains low due to competing reactions.

- Problem: Metabolic flux is diverted to native byproducts.

- Solution: Identify and disrupt key competing pathways.

- Protocol: Knockout of Competing Pathways

- Identify Targets: Use genome-scale models (GEMs) and transcriptomic data to pinpoint genes responsible for undesirable side reactions [32]. For example, in Y. lipolytica, disrupting the β-oxidation pathway prevents degradation of lipid precursors [32].

- Design gRNA: For CRISPR/Cas9 systems, design a guide RNA with high on-target efficiency and minimal off-target effects.

- Verify Knockout: Confirm gene deletion via PCR and sequencing. Validate the phenotypic change, such as the inability to grow on specific carbon sources.

- Assess Impact: Analyze metabolomic and transcriptomic profiles to confirm the redirection of flux and ensure no essential functions are impaired.

Genetic Toolbox and Expression Control

FAQ: What advanced synthetic biology tools can help optimize production beyond simple gene knockouts?

- Subcellular Compartmentalization: Target biosynthetic pathways to organelles like peroxisomes or mitochondria. This concentrates substrates and enzymes, isolates toxic intermediates, and can improve overall efficiency. For instance, compartmentalizing the carotenoid pathway in Yarrowia lipolytica peroxisomes significantly improved yield [32].

- Biosensor-Driven Dynamic Regulation: Implement transcription factor-based biosensors that respond to key metabolites (e.g., acetyl-CoA, malonyl-CoA). These can be used for high-throughput screening of mutant libraries or for building feedback circuits that dynamically regulate pathway gene expression in response to metabolic status [32].

- Lifespan Engineering: In E. coli, engineering the replicative lifespan (RLS) via a two-output recombinase-based state machine (TRSM) has been used to enlarge cell size and create more space for product storage (e.g., polymers). Similarly, modulating the chronological lifespan (CLS) can enhance the production phase [33].

Scaling and Industrial Fermentation

FAQ: What are the critical parameters to monitor when scaling up from shake flasks to bioreactors?

Scaling up introduces challenges related to mass transfer, mixing, and heterogeneous environmental conditions. Key parameters include dissolved oxygen (especially for aerobic processes like antibiotic production in actinomycetes), pH, substrate concentration, and the buildup of inhibitory byproducts. Advanced scale-down models, which simulate large-scale heterogeneity in small-scale bioreactors, are crucial for identifying potential problems early [34].

Troubleshooting Guide: My high-producing lab strain performs poorly in the production bioreactor.

- Problem: Physiological changes or metabolic burdens at scale.

- Solution: Employ a systematic biotechnology framework (like DCEO Biotechnology) that integrates Design, Construction, Evaluation, and Optimization phases. This holistic approach considers not just metabolic capabilities but also the host's physiological state and environmental conditions [33].

- Protocol: Fed-Batch Fermentation for High Titer

- Inoculum Preparation: Grow a seed culture in a rich medium to high cell density.

- Batch Phase: Initiate the fermentation with an initial bolus of carbon and nitrogen sources to achieve rapid growth.

- Fed-Batch Phase: Once the carbon source is nearly depleted, initiate a controlled feed of the limiting nutrient (e.g., glucose or glycerol) to maintain a specific growth rate that maximizes product formation and minimizes byproduct secretion (e.g., acetate in E. coli).

- Process Control: Continuously monitor and control pH, temperature, and dissolved oxygen. Use off-gas analysis to monitor metabolic activity.

- Induction: For inducible systems, add the inducer at the appropriate cell density, which may be optimized for the scaled-up process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Targeted gene knockout, knock-in, and repression [35] | Disrupting competing pathways (e.g., CHS2 in grape cells to enhance resveratrol) [35] |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | In silico prediction of metabolic fluxes and identification of bottlenecks [32] | Guiding strategies for precursor enhancement in Y. lipolytica [32] |

| Biosensors | Dynamic pathway regulation or high-throughput screening [32] | Screening for Y. lipolytica strains with high intracellular malonyl-CoA levels [32] |

| Peroxisomal Targeting Signals (PTS) | Recruiting heterologous enzymes to organelles for pathway compartmentalization [32] | Localizing carotenoid biosynthesis pathway in Y. lipolytica peroxisomes [32] |

| Recombinase-Based State Machines | Precise control of cellular processes like lifespan [33] | Engineering E. coli replicative lifespan to increase polymer storage capacity [33] |

Advanced Tools and Workflows: Pathway Engineering and Synthetic Biology Applications

Pathway reconstruction is a foundational metabolic engineering strategy for optimizing microbial cell factories. It involves the rational design and assembly of biosynthetic routes within a host organism to enable the efficient production of target compounds. This process can entail the modification of native metabolic pathways, the introduction of heterologous genes, or the complete de novo design of novel biochemical routes to enhance yield, titer, and productivity. The ultimate goal is to rewire cellular metabolism, redirecting carbon flux toward the desired product while minimizing energy loss and the formation of byproducts. Successful pathway reconstruction requires a deep understanding of enzyme kinetics, regulatory mechanisms, and the stoichiometric balance of cofactors.

Common Problems & Troubleshooting FAQs

FAQ 1: My microbial cell factory shows low yield of the target product despite high pathway gene expression. What could be wrong?

- Possible Cause: Imbalanced cofactor regeneration (e.g., NADPH/NADP⁺, NADH/NAD⁺) or insufficient supply of key pathway precursors.

- Solution: Reconstruct the pathway to achieve complete redox balance. For example, in isobutanol production, replacing the native Embden-Meyerhof (EM) pathway with the Entner-Doudoroff (ED) pathway can provide a better match of NADH and NADPH cofactors required by the biosynthetic enzymes, thereby improving yield [36]. Alternatively, engineer precursor supply modules (e.g., for acetyl-CoA or carbamoyl phosphate) and NADPH regeneration modules to enhance flux [37].

FAQ 2: How can I reduce the accumulation of metabolic byproducts that compete with my target compound?

- Possible Cause: Native metabolic pathways divert carbon and energy toward the synthesis of organic acids (e.g., acetate, lactate, formate) or other native metabolites.

- Solution: Inactivate genes encoding enzymes for byproduct synthesis. Sequential inactivation of pflB (pyruvate formate lyase), ldhA (lactate dehydrogenase), and pta (phosphate acetyltransferase) has been demonstrated to reduce byproduct formation and improve carbon flux toward target compounds like isobutanol [36].

FAQ 3: I need to evaluate billions of pathway variants to find a high producer. How can I do this efficiently?

- Possible Cause: Conventional screening methods have low throughput and cannot handle vast combinatorial libraries.

- Solution: Implement evolution-guided optimization using biosensors. Couple the intracellular concentration of your target chemical to cell fitness by using a sensor protein that regulates an antibiotic resistance gene. This allows you to apply selective pressure to enrich for high-producing cells from a large, diverse library of pathway variants [38]. A "toggled selection" scheme between negative and positive selection can help eliminate non-productive "cheater" cells that survive without producing the target [38].

FAQ 4: My host strain becomes auxotrophic for an essential nutrient after pathway modifications. How can I overcome this?

- Possible Cause: Blocking a native pathway to prevent carbon loss may also disrupt the synthesis of an essential biomass component, such as an amino acid.

- Solution: Reconstruct a recycling, nonauxotrophic biosynthetic pathway. For L-citrulline production in E. coli, this was achieved by designing a superior recycling pathway that replaced the native linear pathway and by implementing a dynamic toggle switch responsive to cell density to control the expression of a critical gene (argG), eliminating the need for L-arginine supplementation [37].

FAQ 5: The heterologous pathway I introduced places a high metabolic burden on the host, leading to poor growth.

- Possible Cause: Constant, high-level expression of heterologous enzymes consumes cellular resources and can be toxic.

- Solution: Employ dynamic pathway regulation. Use genetic circuits (e.g., quorum-sensing systems) to dynamically control the expression of pathway genes. This allows the cell to prioritize growth in the initial phases before activating the production pathway at high cell density, thereby decoupling growth from production and improving overall titer and productivity [37].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Reconstructing a Central Metabolic Pathway for Redox Balance

This protocol outlines the steps to modify central carbon metabolism in E. coli to utilize the Entner-Doudoroff (ED) pathway for improved isobutanol production [36].

Strain Generation:

- Start with a base strain (e.g., E. coli K-12 MG1655).

- Inactivation of EM pathway: Knock out the pgi gene (encoding glucose-6-phosphate isomerase) to block flux through the glycolytic EM pathway.

- Activation of ED pathway: Knock out gntR, the transcriptional repressor of the ED pathway genes.

- Inactivation of PPP: Knock out the gnd gene (encoding 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase) to block the pentose phosphate pathway, forcing the cell to rely primarily on the ED pathway for glucose catabolism.

- Verification: Confirm the functional switch to the ED pathway using tracer experiments with [1-¹³C]glucose and analyze mass isotopomer distributions of derived metabolites (e.g., TBDMS-derivatized Ala).

Byproduct Reduction:

- Using the ED-dependent strain as a base, sequentially inactivate genes responsible for major byproducts:

- Knock out pflB (pyruvate formate lyase) to reduce formate production.

- Knock out ldhA (lactate dehydrogenase) to reduce lactate production.

- Knock out pta (phosphate acetyltransferase) to reduce acetate production.

- Using the ED-dependent strain as a base, sequentially inactivate genes responsible for major byproducts:

Pathway Enhancement:

- Introduce the heterologous isobutanol biosynthetic pathway genes (e.g., alsS from B. subtilis; ilvC, ilvD from E. coli; kivd, adhA from L. lactis) on a plasmid.

- To further enhance flux through the ED pathway, overexpress the native ED pathway genes (zwf, pgl, edd, eda) from a low-copy-number vector.

Cultivation and Analysis:

- Perform fermentations under defined conditions (e.g., aerobic, with screw-capped tubes after 18h to prevent volatilization).

- Monitor cell growth (OD₆₀₀), glucose consumption, and product formation.

- Quantify isobutanol and organic acid byproducts using methods like HPLC or GC-MS.

Protocol: Evolution-Guided Pathway Optimization using Biosensors

This protocol uses a biosensor to couple product concentration to cell survival, enabling high-throughput selection of optimal pathway variants from a large library [38].

Biosensor (Sensor-Selector) Construction:

- Select a sensory protein (transcriptional regulator or riboswitch) responsive to your target molecule.

- Genetically engineer a circuit where this sensor controls the expression of a reporter gene necessary for survival under selective conditions (e.g., an antibiotic resistance gene like tolC for SDS resistance).

- To minimize "leaky" survival of non-producers, fine-tune the system by:

- Appending a degradation tag (e.g., ssrA tag) to the selector protein.

- Mutating the ribosome binding site (RBS) of the selector gene.

- Using two copies of the sensor gene for tighter repression.

Library Creation:

- Use targeted genome-wide mutagenesis (e.g., MAGE) to create a diverse library of mutants. Target genes are chosen based on computational models like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and can include regulatory regions and coding sequences of key pathway genes.

Toggled Selection Rounds:

- Positive Selection: Grow the library under selective conditions (e.g., presence of antibiotic). Cells that produce sufficient amounts of the target molecule will activate the sensor-selector and survive.

- Negative Selection: Between rounds of positive selection, grow the enriched population under non-selective conditions. Then, apply a counter-selection (e.g., a toxin gene also controlled by the sensor) to kill cells that have mutated to survive without producing the product ("cheaters").

- Repeat this toggle for multiple rounds to progressively enrich the population with high-producing variants.

Validation:

- Isolate individual clones from the final enriched population.

- Characterize production titers in shake-flask or bioreactor cultures to validate the improvement.

Quantitative Data from Case Studies

The following tables summarize key performance metrics from successful pathway reconstruction studies.

Table 1: Performance of E. coli Strains with Reconstructed ED Pathway for Isobutanol Production [36]

| Strain Description | Final Isobutanol Titer (g/L) | Yield (g-Isobutanol/g-Glucose) | Key Genetic Modifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| EM Pathway-dependent (CFTi21) | Not Specified | Lower than CFTi51 | Base isobutanol producer |

| ED Pathway-dependent (CFTi51) | 11.8 | 0.24 | Δpgi, ΔgntR, Δgnd |

| ED, Δlactate (CFTi91) | ~15 (after further mod.) | 0.28 | CFTi51 + ΔldhA |

| ED, Enhanced (CFTi91zpee) | 15.0 | 0.37 | CFTi91 + zwf, pgl, edd, eda overexpression |

Table 2: Evolution-Guided Optimization Results for Various Products [38]

| Target Product | Fold Increase After Evolution | Final Reported Titer | Selection Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naringenin | 36-fold | 61 mg/L | Sensor-selector (TtgR-TolC) |

| Glucaric Acid | 22-fold | Not Specified | Sensor-selector |

Table 3: High-Titer Production of L-Citrulline via Pathway Reconstruction [37]

| Parameter | Performance of CIT24 Strain |

|---|---|

| Titer | 82.1 g/L |

| Yield | 0.34 g/g glucose |

| Productivity | 1.71 g/(L·h) |

| Key Features | Nonauxotrophic, recycling biosynthetic pathway, dynamic regulation of argG. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents for Pathway Reconstruction Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Knockout Tools | Inactivation of native genes to block competing pathways. | Lambda Red recombinering for deleting pgi, gnd, ldhA, pflB, pta [36]. |

| Heterologous Expression Vectors | Introduction of foreign genes for novel pathway construction. | Plasmids for expressing alsS, ilvC, ilvD, kivd, adhA for isobutanol pathway [36]. |

| Biosensor Systems | Coupling intracellular metabolite concentration to a selectable or screenable output. | TtgR regulator for naringenin, MphR for various inducers, used to control tolC or antibiotic resistance genes [38]. |

| Dynamic Regulation Circuits | Decoupling cell growth from product formation to reduce metabolic burden. | Quorum-sensing-based toggle switch for dynamic control of argG in L-citrulline production [37]. |

| Pathway Visualization Software | Visualizing complex metabolic networks and reconstructed pathways for analysis. | Pathway Tools software and its Pathway Collage feature for creating personalized multi-pathway diagrams [39]. |

Pathway and Workflow Diagrams

Reconstruction Workflow: A generalized workflow for rational pathway reconstruction in microbial cell factories.

ED to Isobutanol Pathway: Metabolic map showing the reconstructed Entner-Doudoroff (ED) pathway for glucose consumption and the heterologous pathway for isobutanol production. Yellow dashed lines indicate gene knockouts (Δpgi, Δgnd) that force flux through the ED pathway. Blue arrows represent native ED pathway reactions, and red arrows represent the heterologous isobutanol synthesis steps [36].

Biosensor Selection Cycle: A toggled selection workflow for evolution-guided pathway optimization. A library of pathway variants undergoes positive selection where survival is linked to product concentration via a biosensor. Negative selection is applied between cycles to remove non-productive "cheater" cells, enriching the population for high producers over multiple rounds [38].

CRISPR-based genome editing has revolutionized metabolic engineering by providing unprecedented precision in modifying microbial cell factories. These tools enable researchers to perform targeted gene knockouts, transient knockdowns, and precise gene integrations to optimize metabolic pathways for enhanced production of valuable biochemicals. Within the framework of optimizing microbial cell factories, CRISPR technologies facilitate the systematic removal of competing pathways, fine-tuning of gene expression, and insertion of heterologous genes to maximize product yield and cellular fitness. This technical support center addresses the specific challenges researchers face when implementing CRISPR techniques in microbial systems, providing troubleshooting guidance and proven methodologies to overcome common experimental hurdles.

Troubleshooting Common CRISPR Workflow Issues

FAQs: Addressing Key Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: Why is my gene knockout efficiency low in my microbial host?

- Potential Causes: Inefficient guide RNA (gRNA) design, insufficient Cas9 expression, poor repair via Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ), or low transformation efficiency.

- Solutions:

- Optimize gRNA Design: Use computational tools to select gRNAs with high on-target scores and minimal predicted off-target sites. Ensure the target site is unique in the genome and has an appropriate Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) for your Cas enzyme [40].

- Enhance Cas9 Expression: Use a strong, constitutive promoter that functions well in your specific microbial host. Verify Cas9 codon-optimization for your organism [8].

- Leverage NHEJ: In microbes lacking robust NHEJ, consider co-expressing NHEJ-related proteins or using CRISPR systems that induce single-strand nicks paired with engineered repair mechanisms to enhance knockout outcomes [41] [8].

FAQ 2: How can I minimize off-target effects in CRISPR editing?

- Potential Causes: gRNA binding to genomic loci with sequence similarity to the intended target, high nuclease concentration, or prolonged nuclease activity.

- Solutions:

- Use High-Fidelity Cas Variants: Employ engineered Cas9 variants (e.g., HiFi Cas9) that have been shown to reduce off-target cleavage while maintaining robust on-target activity [42] [40].

- Optimize Delivery and Dosage: Deliver pre-assembled Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes for rapid activity and degradation, reducing the window for off-target events. Titrate the amount of CRISPR components to use the lowest effective dose [40].

- Computational Prediction and Validation: Utilize bioinformatics tools to predict potential off-target sites during gRNA design. Post-editing, validate the edited genome using methods like whole-genome sequencing or specialized assays (e.g., CAST-Seq, LAM-HTGTS) to detect structural variations [42] [43].

FAQ 3: My microbial cell factory shows reduced growth or viability after CRISPR editing. What is the cause?

- Potential Causes: Metabolic burden from heterologous expression of CRISPR machinery, unintended disruption of essential genes or regulatory regions, or the toxicity of double-strand break (DSB) intermediates.

- Solutions:

- Alleviate Metabolic Burden: Use a transient CRISPR system that does not integrate into the genome. After editing, cure the CRISPR plasmid to eliminate the continuous burden of Cas9 and gRNA expression [5].

- Screen for Essential Genes: Prior to editing, perform bioinformatic analyses to ensure target genes are non-essential. For essential gene knockdowns, use CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) for tunable repression instead of knockout [8].

- Mitigate Toxicity: For large-scale integrations, consider using DSB-free methods like prime editing or homology-directed repair (HDR) with high-fidelity templates to avoid persistent DNA damage and the associated stress responses that can impact cellular activity [5] [44].

FAQ 4: I am not achieving precise gene integration via HDR. How can I improve efficiency?

- Potential Causes: Low efficiency of HDR compared to NHEJ, insufficient quantity or quality of the donor DNA template, or poor accessibility of the target genomic locus.

- Solutions:

- Modulate Repair Pathways: Temporarily inhibit key NHEJ proteins (e.g., Ku70/80) using small molecules or genetic knockouts to favor HDR. Note: Recent studies show that some inhibitors, like DNA-PKcs inhibitors, can exacerbate large structural variations; therefore, use inhibitors like those targeting 53BP1 that may present lower risks [42].

- Optimize Donor Template Design: Flank the insert with long homologous arms (≥500 bp for microbes). For single-stranded oligonucleotide donors, protect the ends from degradation by using phosphorothioate linkages. Ensure the donor is provided in high molar excess relative to the CRISPR machinery [41].

- Time the Expression: Synchronize cells to the S/G2 phase of the cell cycle where HDR is more active, or use inducible systems to control the timing of DSB induction relative to donor template availability [42].

FAQ 5: What are the primary safety concerns for therapeutic CRISPR applications, and how are they addressed?

- Potential Causes: Unintended on-target effects (large deletions, structural variations) and off-target mutagenesis.

- Solutions:

- Comprehensive Genomic Analysis: Employ long-read sequencing (e.g., Oxford Nanopore, PacBio) and specialized assays (e.g., CAST-Seq) to detect large-scale on-target deletions and chromosomal translocations that are missed by standard short-read amplicon sequencing [42].

- Advanced Editing Platforms: Utilize more precise editors like prime editing, which does not require DSBs, or base editors for direct chemical conversion of one base to another, significantly reducing the risk of structural variations [44]. Recent research has developed prime editors (vPE) with error rates as low as ~1 in 500 edits [44].

- Rigorous Pre-clinical Testing: Conduct extensive genotoxicity profiling in relevant cell models, including searching for edits in known oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, as required by regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA [42].

Troubleshooting Guide Table

| Problem Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No editing observed | - Inactive Cas9/gRNA complex- Poor delivery into cells- Incorrect target site selection | - Verify protein and RNA integrity- Use a different delivery method (e.g., electroporation)- Check for target accessibility and PAM sequence [8] |

| High off-target activity | - Low-specificity gRNA- High, persistent nuclease expression | - Re-design gRNA using specificity-weighted algorithms- Switch to high-fidelity Cas variants or use RNP delivery [42] [43] |

| Low HDR efficiency | - Dominant NHEJ pathway- Insufficient donor template | - Use NHEJ inhibitors (with caution for SV risk)- Increase donor concentration and optimize design [41] [42] |

| Reduced cell viability | - CRISPR component toxicity- Off-target cuts in essential genes- Metabolic burden | - Use a milder promoter or inducible system- Re-assess gRNA for specificity; switch to CRISPRi- Use a transient CRISPR system and cure the plasmid post-editing [8] [5] |

| Unintended large deletions/translocations | - CRISPR-induced DSB repair errors- Use of DNA-PKcs inhibitors | - Avoid DNA-PKcs inhibitors for HDR enhancement- Characterize edits with long-read sequencing technologies [42] |

Essential Protocols for Microbial Metabolic Engineering

Protocol 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Gene Knockout in Bacteria

Objective: To permanently disrupt a target gene to eliminate a competing metabolic pathway.

Materials:

- Plasmid expressing Cas9 and gRNA, or purified Cas9 protein and in vitro transcribed gRNA for RNP formation.

- Donor DNA oligonucleotide (if using HDR for precise editing).

- Electroporator or chemical transformation reagents.

- Recovery media.

- Selective agar plates.

Methodology:

- gRNA Design: Design a gRNA sequence targeting the 5' end of the gene of interest. Verify specificity using tools like CRISPRon/off [8].

- Construct Assembly: Clone the gRNA expression cassette into a CRISPR plasmid containing a microbial Cas9 gene.

- Delivery: Transform the plasmid or pre-assembled RNP complex into competent microbial cells via electroporation.

- Outcome Analysis: Allow cells to recover, then plate on selective media. Screen individual colonies by colony PCR and Sanger sequencing to identify frameshift mutations caused by NHEJ [41].

Protocol 2: Enhancing Homology-Directed Repair for Gene Integration

Objective: To insert a heterologous gene or repair a mutation with nucleotide precision.

Materials:

- CRISPR plasmid or RNP complex.

- Double-stranded or single-stranded DNA donor template with long homologous arms.

- Optional: Chemical inhibitors of NHEJ (e.g., for 53BP1).

Methodology:

- Donor Design: Create a donor DNA template containing the desired insertion/flanking mutation, flanked by homologous arms (800-1000 bp recommended for microbes).

- Co-delivery: Co-transform the CRISPR components (plasmid or RNP) and the donor DNA into the microbial host.

- Pathway Modulation (Optional): If efficiency is low, add an NHEJ inhibitor to the culture medium post-transformation to transiently bias repair toward HDR. Caution: Validate the absence of major structural variations post-editing [42].

- Screening: Screen clones via PCR and sequencing across the integration junctions to confirm precise insertion [8].