Overcoming the Hurdles: How Machine Learning is Tackling Metabolic Pathway Optimization Challenges

This article reviews the significant challenges in optimizing metabolic pathways for microbial cell factories and drug development, and how machine learning (ML) is providing innovative solutions.

Overcoming the Hurdles: How Machine Learning is Tackling Metabolic Pathway Optimization Challenges

Abstract

This article reviews the significant challenges in optimizing metabolic pathways for microbial cell factories and drug development, and how machine learning (ML) is providing innovative solutions. It explores the foundational obstacles, such as the complexity of cellular machinery and the limitations of trial-and-error approaches. The piece delves into specific ML methodologies, including their application in constructing genome-scale models and predicting pathway dynamics. Furthermore, it examines troubleshooting strategies for data and model limitations and provides a comparative analysis of ML's performance against traditional methods. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current advancements and future directions for integrating ML into metabolic engineering workflows.

The Core Hurdles: Understanding the Foundational Challenges in Metabolic Pathway Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What are the primary bottlenecks in the conventional metabolic engineering cycle? The classic Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle is often hindered by a low learning rate. The "Learn" phase traditionally relies on researcher intuition and time-consuming, low-throughput experiments. This makes it difficult to explore the vast design space of possible genetic modifications efficiently, leading to a slow, iterative process [1].

FAQ 2: How does limited biological knowledge impact pathway optimization? Our understanding of cellular machinery is incomplete. Key mechanisms like allosteric regulation, post-translational modifications, and pathway channeling are often sparsely mapped [2]. This knowledge gap forces researchers to use simplified models (e.g., Michaelis-Menten kinetics) with parameters measured in vitro that may not reflect in vivo conditions, reducing predictive accuracy [1] [2].

FAQ 3: Why is predicting the behavior of engineered metabolic pathways so challenging? Metabolic networks are complex, nonlinear systems. Conventional stoichiometric models can predict metabolic fluxes but ignore enzyme kinetics and cannot capture dynamic metabolic responses [2]. While kinetic models exist, they are slow to develop, require extensive domain expertise, and lack reliable data for enzyme activity and substrate affinity parameters [2].

FAQ 4: What is the specific challenge with annotating metabolites in metabolomics studies? A major limitation in metabolomics is the sparse pathway annotation of detected metabolites. It is common for less than half of the identified metabolites in a dataset to have known metabolic pathway involvement. This makes it difficult to interpret results and understand the biological significance of measured metabolic changes [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Titer/Yield in Engineered Pathway

- Potential Cause: Suboptimal expression of pathway enzymes or unidentified rate-limiting steps.

- Solution: Implement machine learning models to determine the optimal combination of enzyme expression levels. ML can analyze multi-omics data to identify hidden bottlenecks and suggest effective genetic interventions [1].

Problem: Inaccurate Predictions from Kinetic Models

- Potential Cause: Models rely on inaccurate in vitro enzyme turnover numbers (kcats) or lack incorporated regulatory mechanisms.

- Solution: Integrate machine learning-predicted in vivo kcats [1] or replace traditional kinetic modeling with a machine learning approach that learns the system dynamics directly from time-series multiomics (proteomics and metabolomics) data [2].

Problem: Unknown Metabolic Pathway for a Metabolite

- Potential Cause: The metabolite is not annotated in major pathway databases like KEGG or MetaCyc.

- Solution: Employ a machine learning classifier trained on combined metabolite and pathway features. Modern tools like MotifMol3D use molecular structure and motif information to predict pathway involvement with high accuracy, outperforming older methods that required multiple classifiers [3] [4].

Performance Data: Conventional vs. ML-Assisted Approaches

The following table summarizes quantitative comparisons that highlight the limitations of conventional methods and the improvements possible with machine learning.

| Challenge | Conventional Approach & Outcome | ML-Assisted Approach & Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Pathway Identification | Manual curation and database matching; often >50% of metabolites lack pathway annotations [3]. | Single binary classifier using metabolite-pathway feature pairs outperforms combined performance of multiple separate classifiers [3]. |

| Pathway Dynamics Prediction | Michaelis-Menten kinetic modeling; predictions often inaccurate due to unknown parameters and regulation [2]. | ML model trained on multiomics data outperforms classical kinetic model and improves prediction accuracy as more data is added [2]. |

| Genome-Scale Model (GEM) Refinement | Manual gap-filling and curation is tedious and time-consuming [1]. | BoostGAPFILL strategy leverages ML for gap-filling with >60% precision and recall [1]. |

| Enzyme Turnover Number (kcat) Prediction | Reliance on low-throughput in vitro assays that may not reflect in vivo conditions [1]. | ML models predict kcats in vivo using EC numbers, molecular weight, and flux data, leading to improved proteome allocation forecasts [1]. |

| Biological Age Prediction (Health Outlook) | Reliance on chronological age, a poor indicator of biological health and aging [5]. | Cubist ML model on metabolomic data predicts biological age with a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 5.31 years, linking accelerated age to higher mortality risk [5]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Machine Learning for Predicting Metabolic Pathway Dynamics from Multiomics Data

- Objective: To learn a function that predicts the rate of change of metabolite concentrations directly from proteomics and metabolomics data, bypassing the need for a predefined kinetic model [2].

- Methodology:

- Data Collection: Obtain multiple time-series of metabolite and protein concentration measurements (({\tilde{\bf m}}^i[t]), ({\tilde{\bf p}}^i[t])) from different engineered strains (i = 1, ..., q) [2].

- Data Preprocessing: Calculate the time derivatives of the metabolite concentrations (({\dot{\tilde{\bf m}}}^i(t))) from the time-series data to serve as the target output for the model [2].

- Model Training: Frame the problem as a supervised learning task. Use a machine learning algorithm to find a function (f) that solves the optimization problem: (\arg\min{f} \sum{i = 1}^q \sum_{t \in T} \lVert f({\tilde{\bf m}}^i[t],{\tilde{\bf p}}^i[t]) - {\dot{\tilde{\bf m}}}^i(t) \rVert^2) [2].

- Prediction: Once trained, the function (f) can be used to predict the dynamic behavior of new pathway designs by integrating Eq. (1) as an initial value problem [2].

Protocol 2: Predicting Metabolic Pathway Involvement Using Molecular Motifs and Graph Neural Networks

- Objective: To accurately predict the metabolic pathway categories of a molecule based on its chemical structure, enhancing interpretability [4].

- Methodology:

- Feature Extraction (V1): Generate a feature vector for each molecule that includes:

- Motif Descriptors: Identify functional substructures (motifs) from SMILES strings and select the most informative ones using TF-IDF values [4].

- TDB Descriptors: Calculate 3D topological distance-based descriptors using atomic properties (e.g., mass, electronegativity) to capture spatial structural information [4].

- Molecular Property Descriptors: Compute properties like molar refractivity and lipophilicity using RDKit [4].

- Feature Extraction (Graph Features): Use a Graph Attention Network (GAT) to extract features from the molecular graph, combining bond and node information [4].

- Model Architecture & Training: Develop a hybrid framework (e.g., MotifMol3D) that concatenates the V1 and graph features. This is then fed into a feedforward network and a classifier like XGBoost for final pathway category prediction [4].

- Validation: Perform ablation studies and external validation to demonstrate the model's effectiveness and the importance of motif information for interpretability [4].

- Feature Extraction (V1): Generate a feature vector for each molecule that includes:

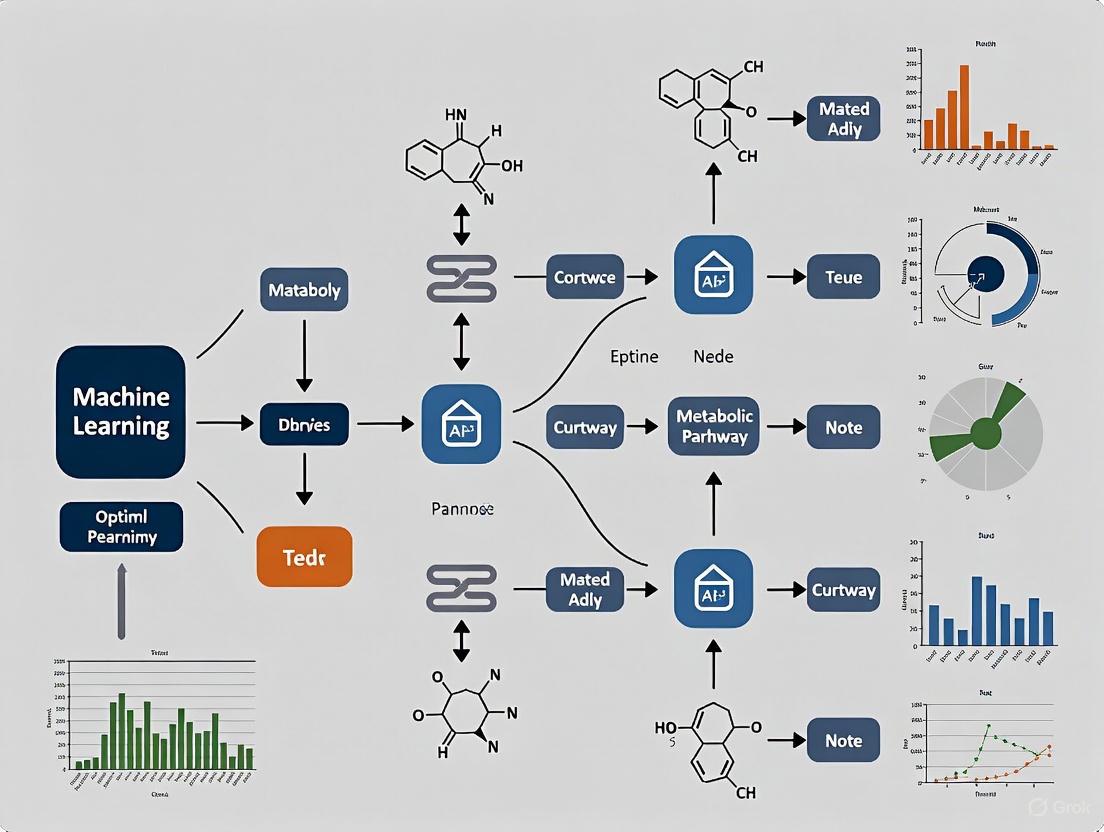

Workflow Visualization: ML-Enhanced DBTL Cycle

The diagram below illustrates how machine learning integrates into and accelerates the traditional DBTL cycle.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| KEGG / MetaCyc Database | Provides reference data on known metabolic pathways and metabolite associations for model training and validation [3] [4]. |

| Molecular Motif Features | Functional substructures within molecules used as descriptors to characterize compounds and enhance model interpretability in pathway prediction [4]. |

| TDB 3D Descriptors | Topological Distance-Based descriptors that provide 3D structural information by relating atomic topology to spatial distance, enriching molecular feature sets [4]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | A deep learning architecture that operates directly on graph-structured data, such as molecular graphs, to extract meaningful features for prediction tasks [4]. |

| Enzyme-Constrained GEM (ecGEM) | A genome-scale model that incorporates enzyme turnover numbers and capacity constraints to provide more accurate simulations of metabolic flux and proteome allocation [1]. |

| Time-Series Multiomics Data | Paired measurements of metabolite and protein concentrations over time, serving as the essential training data for ML models that predict pathway dynamics [2]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary cause of the genotype-to-phenotype knowledge gap? The gap arises from complex genome × environment × management interactions that determine phenotypic plasticity. While high-throughput genotyping and non-invasive phenotyping have advanced rapidly, the large-scale analysis of the underlying physiological mechanisms has lagged behind, creating a bottleneck in understanding how genetic components express themselves in complex traits [6].

2. How can machine learning help in optimizing metabolic pathways? Machine learning (ML) identifies patterns within large biological datasets to build data-driven models for complex bioprocesses. It is integrated into Design–Build–Test–Learn (DBTL) cycles to explore the design space more effectively, helping in genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) construction, multistep pathway optimization, rate-limiting enzyme engineering, and gene regulatory element design [1].

3. My deep learning model for image-based phenotyping is not generalizing well to field data. What should I check? This is a common issue when models trained on controlled lab environments face real-world variations. Key areas to troubleshoot are:

- Input Data: Ensure your training dataset includes sufficient variation in lighting, background, plant pose, and occlusion. Models relying on hand-engineered pipelines are particularly vulnerable to these variations [7].

- Model Validation: Correlate your model's predictions with physiological measurements at the cellular or tissue level (the internal phenotype) to ensure it is a valid proxy for the underlying biological process [6].

4. What are the best practices for handling missing pathway annotations in metabolomics data? It is common for less than half of identified metabolites to have known pathway involvement. A modern ML approach is to use a single binary classifier that accepts features representing both a metabolite and a generic pathway category. This method outperforms training separate classifiers for each pathway category and is more computationally efficient [3].

5. How can I prioritize candidate genes from a large list generated by a GWAS or QTL study? Systematic prioritization requires integrating heterogeneous information. You should use computational tools that build a knowledge network from data such as:

- Known gene-phenotype links and gene-disease associations.

- Gene expression and co-expression data from relevant tissues or conditions.

- Effects of genetic variation on protein function.

- Protein-protein interactions and pathway memberships.

- Homology information from key model species [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inaccurate Predictions from Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs)

Problem: Flux balance analysis (FBA) in a classical GEM produces an underdetermined system with infinite solutions or biologically implausible flux distributions [1].

| Troubleshooting Step | Description | Key Tools/Data to Use |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Check Model Completeness | Identify and fill gaps in the metabolic network draft. | Use tools like BoostGAPFILL, which leverages ML and constraint-based models to suggest missing reactions with >60% precision and recall [1]. |

| 2. Incorporate Enzyme Constraints | Classical GEMs lack enzyme turnover constraints. | Build an enzyme-constrained GEM (ecGEM). Use ML models to predict missing enzyme turnover numbers (kcats) in vivo using features like EC numbers and molecular weight [1]. |

| 3. Refine and Curate the Model | Automate the tedious process of manual curation. | Apply statistical learning methods to produce an ensemble of models and determine uncertainty, reducing the manual refinement workload [1]. |

Issue 2: Poor Performance in Complex Image-Based Phenotyping Tasks

Problem: Traditional image processing pipelines fail at complex tasks like leaf counting, disease detection, or mutant classification, especially when moving from controlled lab settings to the field [7].

Solution Workflow:

Steps:

- Task Definition: Clearly define the complex phenotype (e.g., "count number of leaves," "classify mutant from wild-type").

- Data Acquisition: Collect a large set of raw RGB images under a wide range of conditions (lighting, background, growth stage) to ensure robustness [7].

- Model Selection: Use a platform like Deep Plant Phenomics that provides pre-trained deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for common phenotyping tasks. CNNs integrate feature extraction and classification into a single, end-to-end trainable pipeline, eliminating the need for hand-tuned parameters [7].

- Training & Validation: Train the model. Crucially, validate the model's output against precise physiological or biochemical measurements (the internal phenotype) to ensure it is a meaningful proxy for the biological trait [6].

- Deployment: Use the trained model for high-throughput screening of plant images.

Issue 3: Low Throughput in Optimizing Multistep Metabolic Pathways

Problem: The conventional trial-and-error approach to identify the optimal combination of enzyme expression levels or gene edits is slow and tedious [1].

Solution: Implement an ML-driven framework.

Methodology:

- Design-Build: Construct a diverse library of microbial cell factories with variations in the target pathway (e.g., promoter swaps, enzyme engineering).

- Test: Measure the output (e.g., metabolite titer, yield) using high-throughput fermentation and analytics.

- Learn: Train ML models (e.g., using Bayesian optimization) on the generated dataset to learn the complex relationship between genetic interventions and phenotypic output.

- Predict: Use the trained model to predict which genetic combinations are most likely to improve performance, guiding the next Design-Build cycle [1] [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Deep Plant Phenomics Platform | An open-source deep learning tool that provides pre-trained neural networks for complex plant phenotyping tasks (e.g., leaf counting, mutant classification), enabling high-throughput image analysis [7]. |

| KEGG / BioCyc Databases | Provide curated information on metabolites, enzymes, and biochemical pathways, serving as a gold-standard knowledge base for training and validating machine learning models for pathway prediction [3]. |

| ecGEM (enzyme-constrained GEM) | A genome-scale metabolic model that incorporates enzyme turnover constraints, enabling more accurate simulation of metabolic fluxes, growth rates, and proteome allocation. ML is key for predicting missing kcat values [1]. |

| AnimalQTLdb / GnpIS | Structured databases providing standardized quantitative trait loci (QTL) and genotype-phenotype association data, which are essential for candidate gene discovery and prioritization [8]. |

| Single Binary Classifier Model | A machine learning model architecture that predicts metabolic pathway involvement for a metabolite by using combined features of the metabolite and the pathway, streamlining predictions across multiple pathways [3]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing High Error Rates and Noise in High-Throughput Data

Problem: My high-throughput dataset (e.g., from RNA-seq) has high error rates and significant background noise, leading to unreliable analysis.

Explanation: High-throughput technologies like next-generation sequencing (NGS) and microarrays are inherently prone to technical noise and variability. This often stems from sample preparation artifacts, sequencing errors, or instrumental limitations. This noise can obscure true biological signals, such as genuine differentially expressed genes in a metabolic pathway, and lead to inaccurate model predictions [9].

Solution: Implement a robust data preprocessing and quality control (QC) pipeline.

- Quality Control Metrics: Use established metrics for your data type. For NGS data, this includes per-base sequence quality scores. For microarray data, examine intensity distributions and background noise levels [9].

- Visualization Tools: Generate QC visualizations like box plots to inspect the distribution of quality metrics across samples or heatmaps to visualize overall data structure and identify potential outliers [9].

- Data Cleaning and Filtering: Remove technical artifacts. In NGS, this involves trimming adapter sequences and filtering out low-quality reads. For gene expression data, filter out genes with consistently low expression levels across samples [9].

- Data Normalization: Apply normalization methods like quantile normalization (for microarrays) or transformations like log2 (for count data) to minimize non-biological variation between samples, making them comparable [9].

Prevention: Adopt standardized operating procedures for sample processing, use spike-in controls where applicable, and perform pilot experiments to optimize protocols before large-scale data generation.

Guide 2: Identifying and Correcting for Data Imbalance and Bias

Problem: My machine learning model for classifying metabolic pathway activity is performing poorly because some pathway classes are underrepresented in my training data.

Explanation: Data imbalance occurs when the classes in a classification task are not represented equally. In metabolic engineering, this could mean having few examples of a high-yield strain versus many low-yield ones. This imbalance causes models to become biased toward the majority class, reducing their predictive accuracy for the underrepresented, and often most interesting, classes [10].

Solution:

- Audit for Imbalance: Use tools like IBM’s AI Fairness 360 to detect and quantify bias and class imbalance in your dataset [10].

- Data-Level Strategies:

- Resampling: Oversample the minority class or undersample the majority class to create a balanced dataset.

- Data Augmentation: Generate synthetic data points for the minority class. In bioinformatics, this could involve creating in silico perturbations or using generative models to simulate new samples.

- Algorithm-Level Strategies: Use model cost functions that penalize misclassification of the minority class more heavily than the majority class during training [10].

Prevention: During experimental design, plan for a stratified data collection strategy to ensure all relevant classes are sufficiently represented.

Guide 3: Managing Epistasis and Unpredictable Interactions in Metabolic Pathways

Problem: When I try to optimize a heterologous metabolic pathway by evolving individual enzymes, beneficial mutations in one enzyme often become detrimental when combined, halting progress.

Explanation: This is a classic symptom of epistasis, where the effect of a mutation in one gene depends on the genetic background of other mutations in the pathway. This creates a complex and "rugged" evolutionary landscape, making it difficult to find optimal combinations of enzymes through simple, sequential optimization. Metabolic control theory further complicates this, as improving one enzyme can simply shift the pathway's bottleneck to another enzyme [11].

Solution: Employ a holistic pathway debottlenecking strategy.

- Bottleneck Identification: Use multi-omics data (e.g., metabolomics, proteomics) to identify which step in the pathway is currently rate-limiting. A buildup of the substrate and low output of the product for a specific enzyme is a key indicator [11].

- Parallel Evolution: Instead of evolving enzymes one by one, use automation (biofoundries) to create libraries of variants for all pathway enzymes simultaneously [11].

- Machine Learning-Guided Balancing: Use a predictive machine learning model, trained on the multi-omics and production data from your engineered strains, to identify beneficial combinations of enzyme expression levels and mutations. For example, the

ProEnsemblemodel has been used to optimize promoter combinations to balance transcription of pathway genes, effectively relaxing epistatic constraints [11].

Prevention: When designing a synthetic pathway, consider using enzymes with high specificity and minimal cross-talk, and design the system with dynamic regulation to automatically adjust to metabolic imbalances.

Guide 4: Detecting and Mitigating Data Drift in Continuous Processes

Problem: A model trained to predict product titer in a bioreactor was initially accurate, but its performance has degraded over several months.

Explanation: This is likely data drift, where the underlying data distribution changes over time. In bioprocessing, this can be caused by:

- Concept Drift: The relationship between process variables (like pH, temperature) and the output (titer) changes, perhaps due to microbial evolution or subtle changes in raw materials.

- Input Data Drift: The statistical properties of the input data itself change [10].

Solution:

- Continuous Monitoring: Implement statistical process control (SPC) and algorithms like the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test or Population Stability Index (PSI) to continuously monitor incoming data and compare its distribution to the baseline training data [10].

- Adaptive Model Training: If drift is detected, retrain your model on more recent data. Use ensemble learning techniques that can combine predictions from models trained on different temporal slices of data [10].

- Feature Engineering: Identify and use input features that are more stable and less sensitive to the sources of drift [10].

Prevention: Maintain rigorous documentation of all process parameters and raw material batches. Establish a schedule for periodic model review and retraining.

Guide 5: Debugging a Machine Learning Pipeline with Data Errors

Problem: My ML pipeline for predicting metabolic flux is failing or producing unreliable results, and I suspect the issue lies with the data handling between pipeline steps.

Explanation: In complex ML pipelines, data errors that originate in early stages (e.g., data preprocessing) can propagate and manifest as failures or poor performance in later stages (e.g., model training or prediction). Traditional debugging methods that focus on individual components in isolation often miss these propagation effects [12].

Solution: A holistic debugging approach.

- Data Attribution: Use frameworks like Data Shapley or Influence Functions to quantify the contribution and impact of individual training data points on the final model's predictions. This can help identify erroneous or highly influential data points that may be causing issues [12].

- Pipeline Inspection: In pipeline frameworks like Azure ML, check that the output directory of one step is correctly passed as the input directory to the next. Ensure your script explicitly creates the expected output directory using

os.makedirs(args.output_dir, exist_ok=True)[13]. - Reasoning with Uncertainty: For data errors that cannot be immediately repaired, employ methods that allow the model to reason about the reliability of its predictions in the presence of this uncertainty, rather than attempting a perfect but potentially flawed repair of the data [12].

Prevention: Implement rigorous data validation checks at each step of the pipeline. Use version control for both code and data, and document all data transformations.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common sources of error in high-throughput biological data? Common errors include technical noise from the sequencing or array platforms, batch effects from processing samples at different times or in different labs, mislabeling of samples, and biological variability that is not accounted for in the experimental design [9] [10]. In metabolic engineering, a specific and common error is the presence of epistatic interactions that invalidate assumptions of linear optimization [11].

FAQ 2: How can I quickly assess the quality of a high-throughput dataset? Start by calculating key quality control (QC) metrics specific to your data type (e.g., read quality scores for NGS, intensity distributions for microarrays). Visualize these metrics using plots like box plots, PCA plots, or heatmaps to identify outliers and assess sample-to-sample consistency [9]. For a more automated approach, data valuation methods like DVGS (Data Valuation with Gradient Similarity) can assign a quality score to each sample based on its contribution to a predictive task [14].

FAQ 3: What is the "data bottleneck" in metabolic pathway optimization? The "data bottleneck" refers to the challenge where the ability to generate vast amounts of high-throughput genetic and multi-omics data outpaces our ability to ensure its quality, integrate it effectively, and extract reliable, actionable insights for engineering biological systems. It's not a lack of data, but a lack of high-quality, interpretable data that directly addresses complex biological constraints like epistasis [11] [2].

FAQ 4: Can machine learning help improve data quality, not just analyze the data? Yes, absolutely. Machine learning is increasingly used for data curation. Techniques like Confident Learning can estimate uncertainty in dataset labels and automatically identify label errors [12]. Furthermore, AI-powered data preparation tools can automate data cleaning by intelligently detecting and correcting errors, handling missing values, and eliminating outliers [15].

FAQ 5: We are generating a new high-throughput dataset. What are the key steps to ensure its quality from the start?

- Experimental Design: Plan for biological and technical replicates to account for variability.

- Standardization: Use standardized protocols and controls throughout the process.

- Metadata Collection: Record detailed, structured metadata for every sample.

- Pilot Studies: Run small-scale pilot experiments to optimize protocols before committing to large-scale production.

- QC Integration: Embed QC checkpoints into your workflow to catch issues early [9] [15].

The following tables summarize key quantitative information related to data generation, quality, and market trends.

Table 1: Data Quality Issues and Impact on Machine Learning

| Data Quality Issue | Impact on ML Model | Common Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Data Imbalance [10] | Bias towards majority class; poor prediction of minority classes. | Resampling (over/under), synthetic data generation, cost-sensitive learning. |

| Label Errors [12] [14] | Incorrect learning signals; degraded model accuracy and reliability. | Data valuation (e.g., DVGS, Data Shapley), confident learning, manual re-labeling. |

| Data Drift [10] | Model performance degrades over time as data distribution changes. | Continuous monitoring (e.g., PSI), adaptive model retraining, ensemble methods. |

| High Noise & Outliers [9] [10] | Model learns spurious patterns; convergence issues and unstable predictions. | Robust algorithms (e.g., Random Forests), anomaly detection, data transformation/filtering. |

Table 2: High-Throughput Data Preparation Market Trends (2024-2033)

| Metric | Value / Forecast | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Market Size (2024) | $6.5 Billion | Baseline market value [15]. |

| Expected Market Size (2033) | $27.28 Billion | Projected growth endpoint [15]. |

| Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) | 16.42% | Expected growth rate during 2025–2033 [15]. |

| AI-Powered Tool Adoption (by 2026) | 75% of Businesses | Gartner forecast of businesses using AI for data prep [15]. |

Table 3: Key Parameters for Parallelized ML Pipelines (e.g., Azure ML)

| Parameter | Description | Example Value/Range |

|---|---|---|

mini_batch_size |

Number of files (FileDataset) or size of data (TabularDataset) passed to a single run() call. |

10 files or "1MB" [13]. |

error_threshold |

Number of record/file failures that can be ignored before the entire job is aborted. | -1 (ignore all) to int.max [13]. |

process_count_per_node |

Number of processes per compute node. Best set to the number of GPUs/CPUs on the node. | 1 (default) or higher [13]. |

run_invocation_timeout |

Timeout in seconds for a single run() method call. |

60 (default) [13]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Data Valuation with Gradient Similarity (DVGS) for Quality Assessment

Purpose: To assign a quality value to each sample in a dataset based on its contribution to a predictive task, thereby identifying mislabeled or noisy data [14].

Materials:

- Source dataset to be evaluated.

- Target dataset that defines the predictive task.

- A machine learning model trainable with Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) (e.g., logistic regression, neural network).

- Computational environment (e.g., Python with PyTorch/TensorFlow).

Methodology:

- Model Selection: Choose a differentiable model appropriate for the task on the target dataset.

- SGD Optimization: Train the model on the target dataset using Stochastic Gradient Descent.

- Gradient Similarity Calculation: At each iteration of the training process:

- Compute the gradient of the loss function with respect to the model parameters for a batch from the target dataset.

- For each sample in the source dataset, compute its individual gradient.

- Calculate the cosine similarity between the target batch gradient and each source sample's gradient.

- Value Assignment: Average the cosine similarity scores for each source sample across all training iterations. This average score is the final DVGS value for that sample. A higher value indicates the sample is more useful and aligned with the learning task on the target set [14].

- Filtering: Filter out source samples with low DVGS values to create a cleaner, higher-quality dataset for subsequent model training.

Protocol 2: A Bottlenecking-Debottlenecking Strategy for Pathway Optimization

Purpose: To engineer a microbial chassis with evolved and balanced metabolic pathway genes for high-yield production of a target compound (e.g., naringenin), while overcoming epistatic constraints [11].

Materials:

- Plasmids: Vectors with different copy numbers (e.g., SC101, p15a, ColE1 origins).

- Strains: Production host (e.g., E. coli BL21(DE3)).

- Libraries: Random mutagenesis libraries for each pathway enzyme.

- Screening Assay: A high-throughput assay for the product (e.g., Al³⁺ assay for naringenin).

- Analytical Equipment: HPLC for quantitative validation.

- Biofoundry: Access to automated strain construction and screening is highly beneficial.

Methodology:

- Bottlenecking (Creating a Predictable Landscape):

- Clone the wild-type pathway genes into a low-copy-number plasmid.

- Individually, clone mutagenesis libraries for each pathway gene into a compatible low-copy-number plasmid.

- This low-expression context "bottlenecks" the pathway, simplifying the evolutionary landscape and allowing beneficial mutations for each enzyme to be discovered independently without severe negative epistasis [11].

- Directed Evolution:

- Screen the individual enzyme libraries in the bottlenecked context using the high-throughput assay (e.g., Al³⁺ assay).

- Select top-performing variants for each enzyme and validate product titer quantitatively (e.g., via HPLC).

- Characterize kinetic parameters ((KM), (k{cat})) of improved enzyme variants [11].

- Debottlenecking (Re-assembly and Balancing):

- Assemble the best-performing evolved enzyme variants into a single, high-copy-number expression vector to form the complete, evolved pathway.

- Machine Learning-Based Balancing: To fine-tune the pathway and relax any remaining epistasis, use a model like

ProEnsemble. Train it on data from strains with different promoter combinations controlling the expression of the evolved pathway genes. The model will predict the optimal promoter set to maximize flux and final product titer [11].

- Validation: Construct the final chassis strain with the ML-predicted optimal genetic configuration and measure the final product yield in a bioreactor.

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Metabolic Pathway Optimization with ML

High-Throughput Data Analysis Workflow

ML-Guided Dynamic Pathway Prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids with Different Copy Numbers | To vary gene dosage for identifying and manipulating metabolic bottlenecks. | SC101 (5-10 copies), p15a (10-15), ColE1 (20-30), RSF (100 copies) [11]. |

| Random Mutagenesis Libraries | To generate genetic diversity for directed evolution of pathway enzymes. | Created for each enzyme gene (TAL, 4CL, CHS, CHI) in the naringenin case [11]. |

| High-Throughput Screening Assay | To rapidly screen thousands of microbial variants for desired product formation. | Al³⁺ assay for flavonoids like naringenin [11]. |

| Analytical Instrument (HPLC) | For precise, quantitative validation of metabolite concentrations and yields. | Used to confirm naringenin titers after screening [11]. |

| Data Valuation Algorithm (DVGS) | To algorithmically assess data quality and identify mislabeled or noisy samples. | Scalable, robust to hyperparameters, uses gradient similarity [14]. |

| Influence Functions / Data Shapley | To quantify the importance and contribution of individual data points to a model's predictions. | Used for debugging models and identifying dataset errors [12]. |

| Machine Learning Model (ProEnsemble) | To predict optimal genetic configurations (e.g., promoter combinations) for pathway balancing. | Applied to optimize transcription in the naringenin pathway [11]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Challenges & Solutions

Problem: Inaccurate Flux Predictions in Kinetic Models

- Question: Why does my kinetic model produce inaccurate flux predictions, even with correct stoichiometry?

- Investigation: First, verify the source and assay conditions of the kinetic parameters (e.g., ( k{cat} ), ( Km )) used in your model. Significant differences often exist between in vitro measured parameters and in vivo conditions due to post-translational modifications, cellular crowding, and allosteric regulation [16] [1].

- Solution: Implement a grey-box modeling approach. Use a traditional kinetic model but add an adjustment term to account for the discrepancy between in vitro and in vivo conditions. This hybrid method has been shown to provide more satisfactory predicted fluxes than pure white-box (detailed kinetics) or black-box (pure machine learning) models alone [16].

Problem: Handling Missing Pathway Annotations and Incomplete Data

- Question: How can I proceed with metabolic modeling when a large portion of metabolites have unknown pathway involvement?

- Investigation: Check the sparsity of your pathway annotations. It is common for less than half of identified metabolites in a dataset to have known metabolic pathway involvement [3].

- Solution: Employ a machine learning model trained on combined metabolite and pathway features. Instead of training a separate classifier for each pathway category, use a single binary classifier that accepts features representing both a metabolite and a generic pathway category. This method outperforms previous approaches and requires fewer computational resources [3].

Problem: Selecting the Right Modeling Approach for Limited Data

- Question: My experimental data on enzyme activities and pathway flux is limited. Which modeling approach should I use?

- Investigation: Evaluate the quantity and quality of your available data. Do you have detailed enzyme kinetic parameters and mechanism-based rate equations, or mainly input-output data (e.g., enzyme activity vs. pathway flux)?

- Solution: For small datasets, a black-box approach using Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) can be effective. A typical feed-forward network with a single hidden layer can be trained on enzyme activities to predict pathway flux. To prevent overfitting with limited data, use a Leave-One-Out cross-validation (LOOcv) procedure [16].

Machine Learning-Specific Workflow Issues

Problem: Model Interpretability in Black-Box Approaches

- Question: The ANN model provides accurate flux predictions, but I cannot determine the main flux-controlling enzymes. How can I identify key regulatory points?

- Investigation: Assess the model's output. While ANNs have great predictive and generalization abilities, their high complexity can make them less satisfactory for extracting mechanistic insights [16].

- Solution: Use the black-box model for prediction, but complement it with Metabolic Control Analysis (MCA) on a white-box or grey-box model of the same system. Calculate the flux control coefficients (({C}_{E}^{J})) for each enzyme to identify which enzymes exert the most control over the pathway flux [16].

Problem: Integrating Machine Learning with Genome-Scale Models

- Question: How can I incorporate enzyme kinetics constraints into a Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) to improve its predictions?

- Investigation: Classical GEMs are often constrained only by stoichiometry, leading to underdetermined systems with infinite solutions. The accuracy of enzyme-constrained GEMs (ecGEMs) is limited by the scarcity of experimentally measured enzyme turnover numbers ((k_{cats})) [1].

- Solution: Use a machine learning method to predict (k_{cats}). Integrate features like EC numbers, molecular weight, and in silico flux predictions to parameterize your ecGEM. This approach has been shown to improve forecasts of proteome allocation and metabolic flux distribution [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the main categories of metabolic pathway modeling, and when should I use each? The three primary approaches, as defined in recent scientific literature, are [16]:

- White-Box Modeling: Uses detailed kinetic information, enzyme parameters, and mechanism-based rate equations. Use this when you have a comprehensive understanding of the system's biochemistry and reliable kinetic parameters.

- Grey-Box Modeling: Uses a traditional kinetic model with an added adjustment term. This is ideal when your knowledge of the system is incomplete, and you need to account for discrepancies between model and reality.

- Black-Box Modeling: Uses data-driven methods like Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) to model the relationship between inputs and outputs without requiring detailed mechanistic knowledge. Use this when you have sufficient experimental data but lack detailed kinetic information.

FAQ 2: Why are pathway features sometimes more important than metabolite features in machine learning predictions? Research on predicting pathway involvement has shown that the features related to the pathways themselves can be more predictive than the specific characteristics of a single metabolite. This is because the pathway features encapsulate information about the network context and the collective properties of all metabolites known to be associated with that pathway, providing a richer signal for the classifier [3].

FAQ 3: Our goal is to optimize a multistep pathway in a microbial cell factory. How can machine learning accelerate this? ML can be integrated into the Design–Build–Test–Learn (DBTL) cycle. It helps explore the vast design space more effectively by [1]:

- Identifying Features: Building models to identify key features within large biological datasets.

- Optimizing Expression: Determining the optimal combination of enzyme expression levels for a pathway.

- Enzyme Engineering: Improving the performance of rate-limiting enzymes through ML-based workflows.

- Regulatory Element Design: Aiding in the design of gene regulatory elements (GREs) to fine-tune expression.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Developing a Grey-Box Kinetic Model

This protocol is adapted from studies modeling the second part of E. histolytica glycolysis [16].

1. Objective: To build a hybrid kinetic model that combines mechanistic knowledge with a data-driven adjustment term to accurately predict pathway flux.

2. Materials and Software:

- Software: COPASI (COmplex PAthway SImulator) software [16].

- Data: Experimental data on enzyme activities and measured pathway flux (Jobs). If not from your own experiments, data can be extracted from published plots using tools like WebPlotDigitizer.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Construct the White-Box Base Model.

- In COPASI, reconstruct the metabolic pathway with all relevant metabolites.

- Define the rate equations for each enzyme based on their known kinetic mechanisms (e.g., Michaelis-Menten, Bi-Bi).

- Input the initial, experimentally measured kinetic parameters ((k{cat}), (Km)) and enzyme activities.

- Step 2: Introduce the Grey-Box Adjustment.

- Add an adjustment term to the model. This can be a scalar multiplier for a key enzyme activity or a term added to a rate equation.

- The purpose of this term is to correct for the difference between the in vitro measured enzyme parameters and the actual in vivo behavior.

- Step 3: Parameter Estimation.

- Use the parameter estimation task in COPASI.

- Fit the adjustment parameter(s) by using the experimentally measured pathway flux as the target.

- The software will iteratively adjust the parameter until the model's flux prediction (Jpred) matches the experimental data (Jobs) as closely as possible.

- Step 4: Model Validation.

- Validate the final grey-box model by testing its predictive power on a separate dataset not used during the parameter estimation.

4. Outcome: A kinetic model that reliably predicts pathway flux and can be used for subsequent Metabolic Control Analysis to identify flux control coefficients [16].

Protocol: Training an ANN for Flux Prediction (Black-Box Approach)

1. Objective: To create a data-driven model using Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) to predict metabolic pathway flux from enzyme activity data.

2. Materials and Software:

- Software: RStudio with the

NeuralNet(Version 1.44.2) andNnet(Version 7.3-12) packages [16]. - Data: A dataset where inputs are enzyme activities (e.g., PGAM, ENO, PPDK) and the output is the corresponding pathway flux.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Network Design.

- Design a typical feed-forward network with three layers: an input layer (number of nodes = number of enzyme inputs), a single hidden layer, and an output layer (one node for the predicted flux, Jpred).

- Weights (w~i~ and w'~j~) are assigned to each connection.

- Step 2: Select Hidden Units and Activation Function.

- The number of artificial neurons in the hidden layer is selected by minimizing the Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE). An equation for estimation is: ( Nh = Ns / [\alpha * (Ni + No)] ), where ( Ns ) is the number of training samples, and ( Ni ) and ( N_o ) are the numbers of input and output nodes [16].

- Use a non-linear activation function like the logistic (log) or hyperbolic tangent (tanh).

- Step 3: Model Training and Optimization.

- With small datasets, train the model using the entire dataset and optimize it through Leave-One-Out cross-validation (LOOcv).

- Use the back-propagation method or the Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno (BFGS) method for optimization [16].

- Step 4: Performance Evaluation.

- Evaluate the final model's performance on a separate test set (e.g., data generated from a separate grey-box model) using RMSE and MAE metrics.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Different Pathway Modeling Approaches

This table summarizes the comparative performance of white-, grey-, and black-box modeling approaches as applied to a metabolic pathway study [16].

| Modeling Approach | Key Characteristic | Predictive Accuracy for Flux | Advantage | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White-Box | Detailed kinetic information & parameters | Satisfactory | High mechanistic interpretability | Relies on complete, accurate kinetic data |

| Grey-Box | Kinetic model + data-driven adjustment term | Satisfactory (preferred) | Accounts for in vitro/in vivo discrepancy | Adjustment term may lack direct biological meaning |

| Black-Box (ANN) | Artificial Neural Network trained on data | Satisfactory (excellent generalization) | Does not require prior mechanistic knowledge | Low interpretability; high complexity (AIC value) |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Pathway Modeling

This table details essential resources, including databases and software, critical for conducting research in this field [3] [16] [17].

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application | Reference / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| KEGG Database | Database | Provides curated information on metabolites, enzymes, and biochemical pathways for model training and validation. | KEGG [3] [17] |

| COPASI | Software | Open-source software for building, simulating, and analyzing kinetic models of biochemical networks (white-box & grey-box). | COPASI [16] |

| WebPlotDigitizer | Software Tool | Free online tool to extract numerical data from published plots and images, helping to build datasets from existing literature. | WebPlotDigitizer [16] |

| RStudio with NeuralNet/Nnet | Software / Library | Integrated development environment for R; used to design, train, and evaluate Artificial Neural Network (ANN) models. | RStudio [16] |

| BioCyc Database | Database | Collection of curated pathway/genome databases, useful for pathway annotation and model construction. | BioCyc [3] |

| BoostGAPFILL | Algorithm / Tool | ML-based strategy for generating hypotheses to fill gaps in draft metabolic network models. | [1] |

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: Three Modeling Approaches for Metabolic Pathways

Diagram 2: ML-Integrated DBTL Cycle for Pathway Optimization

ML in Action: Methodologies for Pathway Prediction, Reconstruction, and Dynamic Modeling

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary sources of error in automated genome annotation for GEMs, and how can ML improve accuracy?

Error sources include the limited accuracy of homology-based methods, misannotations in databases, genes of unknown function, and "orphan" enzyme functions that cannot be mapped to a genome sequence [18]. Machine learning improves accuracy by identifying subtle sequence features that homology searches may miss. For instance, DeepEC uses convolutional neural networks to predict Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers directly from protein sequences with high precision [1]. Furthermore, tools like AlphaGEM leverage proteome-scale structural alignment and protein-language-model-based inference (PLMSearch) to identify more homologous relationships than sequence-BLAST-based methods, leading to more reliable metabolic networks [19].

FAQ 2: Automated gap-filling often proposes incorrect reactions. What ML strategies exist to generate more biologically relevant solutions?

Traditional parsimony-based gap-fillers can propose reactions that, while mathematically sound, are biologically irrelevant for the organism's specific conditions (e.g., anaerobic lifestyle) [20]. ML strategies address this by using contextual data to constrain solutions. BoostGAPFILL leverages ML and constraint-based models to generate gap-filling hypotheses constrained by metabolite patterns in the incomplete network, achieving over 60% precision and recall [1]. MetaPathPredict uses a gradient-boosted trees and neural network ensemble to predict the presence of complete metabolic modules even in incomplete genome data, effectively filling multiple related gaps simultaneously [21]. These methods integrate various data types to prioritize solutions that are consistent with the organism's biology.

FAQ 3: How can I resolve conflicting predictions from multiple GEMs of the same organism built with different tools?

Consensus modeling is an effective approach. The GEMsembler Python package is specifically designed to compare GEMs from different reconstruction tools, track the origin of model features, and build a single consensus model [22]. This consensus model can be curated using an agreement-based workflow. Studies show that GEMsembler-curated consensus models for Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Escherichia coli outperformed gold-standard models in predicting auxotrophy and gene essentiality [22].

FAQ 4: How can ML help parameterize advanced enzyme-constrained GEMs (ecGEMs) where kinetic data is scarce?

A major challenge in building ecGEMs is the lack of genome-scale enzyme turnover numbers ((k{cat})), which are typically measured via low-throughput assays [1]. ML models can predict (k{cat}) values by integrating features such as EC numbers, molecular weight, in silico flux predictions, and assay conditions [1]. These predicted parameters allow for more accurate simulation of proteome allocation and metabolic fluxes, improving the predictive power of ecGEMs for metabolic engineering.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Draft GEM fails to produce essential biomass precursors during simulation.

Solution: Implement a probabilistic, ML-driven gap-filling pipeline.

- Diagnosis: Use FBA to identify which biomass metabolites cannot be produced. This pinpoints the metabolic gaps [20].

- Action Protocol:

- Tool Selection: Employ a tool like OMics-Enabled Global Gapfilling (OMEGGA) in KBase, which is designed for iterative model building and gap-filling [21].

- ML-Guided Hypothesis Generation: Use MetaPathPredict to predict the presence of entire metabolic modules that could fill the gap, even with incomplete genome data [21].

- Gene-Function Linking: For non-homologous proteins, use Snekmer, a k-mer-based framework, to model novel protein function families and assign candidate genes to the gap-filled reactions [21].

- Validation: Check that the gap-filled model can now produce all biomass precursors and validate the growth prediction against experimental data if available.

Problem: Model predicts growth on substrates the organism cannot utilize in the lab.

Solution: Curate the model's reaction set using ML-informed annotation and consensus.

- Diagnosis: The model likely contains incorrect reactions from overzealous annotation.

- Action Protocol:

- Re-annotate the Genome: Run the genome through a more precise annotation tool like AlphaGEM, which uses structural alignment and deep learning to minimize false-positive annotations [19].

- Build a Consensus: Use GEMsembler to compare your model with other automatically generated models for the same organism [22]. Reactions absent from all other models are high-priority candidates for removal.

- Incorporate Regulatory Constraints: If possible, integrate transcriptomic data to deactivate reactions when the corresponding genes are not expressed, creating a more context-specific model [23] [18].

Problem: ecGEM simulations do not match experimentally observed metabolic shifts.

Solution: Refine enzyme constraint parameters using ML predictions.

- Diagnosis: The default (k_{cat}) values used to constrain reaction fluxes are inaccurate.

- Action Protocol:

- Acquire Predicted (k{cat}) Values: Use published ML models that predict (k{cat}) values in vivo and in vitro based on enzyme features [1].

- Parameterize the Model: Integrate these predicted (k_{cat}) values into your ecGEM framework (e.g., using the GECKO toolbox approach) [1] [23].

- Test and Validate: Re-run simulations of metabolic shift conditions (e.g., different carbon sources) and compare the predicted fluxes and growth rates against experimental 13C fluxomics or growth data [1].

Performance Data of ML Tools

The table below summarizes the quantitative performance of several ML tools discussed, providing a basis for selection.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Key Machine Learning Tools for GEM Construction

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Reported Performance | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| BoostGAPFILL [1] | Network Gap-filling | >60% Precision and Recall [1] | Leverages metabolite patterns for biologically relevant solutions. |

| DeepEC [1] | EC Number Prediction | High Precision, High-Throughput [1] | Predicts EC numbers directly from protein sequences. |

| AlphaGEM [19] | End-to-end GEM Construction | Predictions comparable to manually curated models [19] | Integrates structural alignment and deep learning for dark metabolism. |

| MetaPathPredict [21] | Metabolic Module Prediction | Accurate prediction with up to 60-70% of genome missing [21] | Enables gap-filling for highly incomplete genomes/MAGs. |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a robust, ML-integrated workflow for GEM construction and refinement, synthesizing the methodologies from the cited research.

ML-Enhanced GEM Construction Workflow

This table lists key computational tools and platforms essential for implementing the ML-driven GEM construction strategies discussed.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for ML-Driven GEM Development

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in GEM Construction |

|---|---|---|

| KBase (KnowledgeBase) [18] [21] | Integrated Platform | Cloud-based environment hosting tools for automatic draft GEM generation, omics data integration, and gap-filling (e.g., OMEGGA). |

| AlphaGEM [19] | Software Pipeline | End-to-end GEM construction using protein structure and deep learning for superior annotation and dark metabolism mining. |

| GEMsembler [22] | Python Package | Compares GEMs from different tools and builds high-performance consensus models. |

| CarveMe [23] [18] | Reconstruction Tool | Creates organism-specific models by carving out reactions from a universal database, using a top-down approach. |

| ModelSEED [23] [18] | Framework & Database | Supports the rapid automated reconstruction, analysis, and simulation of GEMs. |

| Pathway Tools [20] [23] | Software Suite | Creates PGDBs and includes the MetaFlux tool with GenDev gap-filler for model construction and analysis. |

| Snekmer [21] | Computational Framework | Uses k-mer based modeling for novel protein family identification, aiding gene assignment for gap-filled reactions. |

| MetaPathPredict [21] | Machine Learning Tool | Predicts complete metabolic modules in incomplete genomes, enabling efficient large-scale gap-filling. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the core difference between traditional and GNN-based approaches for predicting pathway presence? Traditional methods like Logistic Regression rely on manually curated features from the metabolic network. In contrast, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) learn these features directly from the graph structure of the metabolism, capturing complex topological relationships between reactions that are often missed by manual curation [24].

My GNN model for predicting gene essentiality is not converging. What could be wrong? This is often related to the node featurization step. Ensure your input features, such as the reaction fluxes from Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), are correctly normalized. Also, verify the construction of your Mass Flow Graph, particularly the edge weights representing metabolite flow, as incorrect graph topology will prevent the model from learning meaningful patterns [24].

How can I predict dynamic pathway behavior instead of a static presence/absence output? You can frame this as a supervised learning problem on time-series multiomics data. By using proteomics and metabolomics measurements over time as input features, a machine learning model can be trained to predict the derivative of metabolite concentrations, effectively learning the underlying dynamics without pre-defined kinetic equations [25].

Why would I use a GNN over a standard FBA simulation for predicting gene essentiality? While FBA assumes that both wild-type and knockout strains optimize the same growth objective, this assumption often breaks down for mutants. A GNN model like FlowGAT learns directly from wild-type FBA solutions and experimental knockout data, capturing suboptimal survival strategies of mutants without relying on this potentially flawed assumption [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Accuracy in Logistic Regression Predictions

Background: Logistic Regression (LR) serves as a strong baseline model. Poor performance often indicates issues with the feature set.

Diagnosis and Solution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Audit Feature Correlations | Identify and remove highly collinear features (e.g., using Variance Inflation Factor). |

| 2 | Inspect Feature Importance | Use the model's coefficients to find and retain the most predictive features. |

| 3 | Validate Data Labels | Confirm the ground truth data (e.g., pathway presence from databases like Reactome [26]) is accurate and consistent. |

Problem: Graph Neural Network Fails to Generalize

Background: GNNs like FlowGAT can overfit to the training data, especially with limited labeled examples.

Diagnosis and Solution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Simplify Model Architecture | Reduce the number of GNN layers to prevent over-smoothing from excessive message passing. |

| 2 | Apply Regularization | Introduce Dropout and L2 regularization within the GNN layers to penalize complex weights. |

| 3 | Augment Training Data | Leverage data from multiple growth conditions or related organisms to increase dataset size and diversity [24]. |

Problem: Incorrect Graph Construction from Metabolic Network

Background: The performance of a GNN is critically dependent on a correctly structured input graph.

Diagnosis and Solution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify Stoichiometric Matrix | Ensure the S matrix correctly encodes metabolite-reaction relationships. A single error can corrupt the entire graph. | |

| 2 | Check Mass Flow Calculations | Confirm that edge weights are calculated correctly using the formula for Flow_i→j(X_k) [24]. |

Accurate, directed, and weighted edges in the Mass Flow Graph. |

| 3 | Validate Graph Connectivity | Ensure the graph is not disconnected and that all nodes (reactions) are reachable from appropriate inputs. |

Data Presentation: Method Comparison & Performance

Table 1: Comparison of Pathway Prediction Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Data Requirements | Key Advantages | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | Statistical model predicting a binary outcome based on input features. | Curated feature set (e.g., reaction fluxes, topological metrics). | Simple, fast, highly interpretable, strong baseline. | Relies on manual feature engineering; cannot capture complex network topology. |

| Classical Kinetic Modeling | Uses differential equations with mechanistic rate laws (e.g., Michaelis-Menten). | Detailed enzyme kinetic parameters, metabolite & protein concentrations. | Mechanistically grounded; can predict dynamic behavior. | Requires parameters that are often unknown; slow to develop and scale [25]. |

| FBA with Machine Learning | Uses flux distributions from FBA as features for a machine learning model. | Genome-scale model, FBA solutions, training labels. | Leverages mechanistic FBA insights; more accurate than FBA alone for gene essentiality [24]. | Inherits FBA's optimality assumption for wild-type. |

| Graph Neural Networks (e.g., FlowGAT) | Deep learning on graph-structured data of the metabolic network. | Metabolic network (stoichiometry), FBA solutions, training labels. | Learns directly from network structure; superior accuracy; captures non-optimal mutant states [24]. | "Black-box" nature; requires more data and computational resources. |

Table 2: Example GNN Performance onE. coliGene Essentiality Prediction

| Model Architecture | Growth Condition | Accuracy | Key Performance Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| FlowGAT | Glucose | ~90% | Approaches accuracy of FBA gold standard without optimality assumption for mutants [24]. |

| FlowGAT | Glycerol | ~88% | Generalizes well to other carbon sources without retraining [24]. |

| FlowGAT | Acetate | ~85% | Maintains high prediction accuracy across diverse nutritional environments [24]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Baseline Logistic Regression Model

Purpose: To establish a performance benchmark for pathway presence prediction.

- Feature Extraction: From a genome-scale metabolic model (GEM), calculate a set of features for each reaction. These can include:

- FBA-derived: Wild-type flux value (

v*), flux variability, shadow price. - Topological: Node degree, betweenness centrality, shortest path to key metabolites.

- FBA-derived: Wild-type flux value (

- Label Assignment: Obtain ground truth labels from databases like Reactome [26] or experimental essentiality screens [24].

- Model Training: Split data into training (70%) and testing (30%) sets. Train an LR model using scikit-learn, optimizing regularization strength (

Cparameter) via cross-validation. - Validation: Evaluate the model on the held-out test set using AUC-ROC and precision-recall curves.

Protocol 2: Implementing a FlowGAT Model for Gene Essentiality

Purpose: To predict gene essentiality using a graph neural network on metabolic flux data [24].

- Graph Construction (Mass Flow Graph):

- Nodes: Represent enzymatic reactions from the GEM.

- Edges: Connect two nodes if a metabolite produced by the source reaction is consumed by the target reaction.

- Edge Weights: Calculate using the mass flow formula:

Flow_i→j(X_k) = Flow_Ri+(X_k) * [Flow_Rj-(X_k) / Σ_ℓ Flow_Rℓ-(X_k)][24]. This quantifies the normalized metabolite flow between reactions.

- Node Featurization: For each reaction node, create a feature vector from the wild-type FBA solution (e.g., flux value, reaction bounds).

- Model Training:

- Use a Graph Attention Network (GAT) layer for message passing, allowing nodes to weight neighbor importance.

- Train the model on a binary classification task (essential vs. non-essential) using cross-entropy loss and a labeled dataset.

- Model Interpretation: Analyze the attention weights from the GAT layer to identify which neighboring reactions in the graph were most influential for each prediction.

Mandatory Visualization

Diagram 1: Pathway Prediction Method Evolution

Diagram 2: FlowGAT Architecture for Essentiality Prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Predictive Modeling

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) | A computational reconstruction of an organism's metabolism. Serves as the foundational network for generating features (for LR) or the entire graph structure (for GNNs) [24]. |

| Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | A mathematical matrix representing the stoichiometry of all metabolic reactions in the network. It is the primary input for FBA and for constructing the graph topology [24]. |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | A constraint-based optimization method used to predict steady-state metabolic flux distributions. Provides wild-type flux features for models and weights for graph edges [24]. |

| Knock-out Fitness Assay Data | Experimental data measuring the survival impact of gene deletions. Serves as the essential "ground truth" labels for training and validating supervised models like FlowGAT [24]. |

| Graph Neural Network Library (e.g., PyTorch Geometric) | A software library specifically designed for implementing GNNs. Provides pre-built layers (like GAT) and utilities for handling graph-structured data, drastically accelerating model development [27] [24]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Multiomics Metabolic Flux Analysis

FAQ 1: My flux predictions are inconsistent with my transcriptomic data. What could be the cause?

This is a common issue where gene expression changes do not directly translate to flux changes due to multi-level metabolic regulation [28].

- Problem: A reaction enzyme shows significant upregulation in transcriptomic data, but the predicted metabolic flux for that reaction does not increase.

- Solution:

- Check for Metabolic Control: The reaction might be under metabolic (substrate-level) control. If the substrate concentration is low (near or below the Km of the enzyme), the flux will be insensitive to changes in enzyme concentration [28]. Validate with intracellular metabolomics data.

- Investigate Network Effects: The reaction could be constrained by downstream reactions or network bottlenecks. Use Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to analyze the system-wide flux distribution and identify such constraints [29] [30].

- Review GPR Associations: Ensure the Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) rules in your metabolic model are correct. An incorrect association can lead to miscalculated enzyme activity from transcript levels [28].

FAQ 2: How can I handle missing or incomplete metabolomics data when building my model?

Missing data can lead to gaps in the metabolic network and unreliable flux predictions.

- Problem: Key intracellular metabolites are not measured, creating gaps in the network and unreliable flux predictions.

- Solution:

- Implement Machine Learning Imputation: Train a model (e.g., a Random Forest classifier) on known metabolite-pathway associations from databases like KEGG or MetaCyc to predict the involvement of metabolites in pathways, thereby filling data gaps [3].

- Leverage Gap-Filling Algorithms: Use computational tools that leverage network topology and flux consistency principles to identify and fill gaps in the metabolic network, ensuring all metabolites can be produced and consumed [31].

- Integrate Transcriptomic Data as a Proxy: In the absence of direct metabolomic measurements, use transcriptomic data of enzymes to infer potential flux changes, but always interpret results with caution and in the context of the network [28].

FAQ 3: My model fails to predict known physiological behaviors. How can I improve its accuracy?

This often indicates a problem with the model's constraints or its integration with experimental data.

- Problem: The genome-scale model fails to recapitulate known biological functions, such as biomass production or known secretion profiles.

- Solution:

- Refine Model Constraints: Revisit the constraints applied to the model. Use INTEGRATE or similar pipelines to integrate transcriptomics and metabolomics data as constraints on reaction fluxes, which helps steer the model towards physiologically relevant states [28].

- Incorporate Regulatory Information: The model may lack regulatory rules. Use Bayesian Factor Modeling to infer pathway cross-correlations and activation, adding a regulatory layer beyond stoichiometry alone [29].

- Validate with Experimental Flux Data: If available, use experimentally determined flux data (e.g., from 13C-labeling experiments) to validate and further constrain the model, ensuring it reflects real cellular physiology [30].

FAQ 4: What is the best way to integrate data from multiple omics layers (e.g., transcriptomics and metabolomics)?

Effective integration is key to understanding hierarchical metabolic control [28].

- Problem: Uncertainty in how to combine disparate omics datasets into a single modeling framework.

- Solution: Adopt a structured pipeline like INTEGRATE:

- Use a Metabolic Model as a Scaffold: Map your multiomics data onto a genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) [28] [30].

- Compute Differential Reaction Expression: From transcriptomics data, calculate changes in reaction enzyme levels using GPR rules [28].

- Predict Flux from Metabolomics: Use metabolite abundance data to predict how substrate availability influences fluxes [28].

- Intersect the Datasets: The integration of these two parallel analyses allows you to discriminate whether a reaction's flux is controlled at the metabolic, gene expression, or a combined level [28].

Key Computational Tools and Pipelines for Multiomics Integration

Table 1: Essential computational frameworks for multiomics metabolic flux analysis.

| Tool/Pipeline Name | Primary Function | Key Inputs | Primary Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| INTEGRATE [28] | Model-based multi-omics integration to characterize metabolic regulation. | Transcriptomics, Metabolomics, GEM | Classification of reactions into metabolic, transcriptional, or combined control. |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [29] [30] | Predicts steady-state metabolic fluxes to optimize a cellular objective (e.g., growth). | GEM, Nutrient uptake rates | System-wide flux distribution. |

| Hybrid FBA & Bayesian Modeling [29] | Detects pathway cross-correlations and predicts temporal pathway activation. | Gene expression profiles, GEM | Pathway activation profiles and correlation networks. |

| Machine Learning Classifier [3] | Predicts metabolic pathway involvement for metabolites. | Metabolite chemical structure, Pathway features | Probability of a metabolite belonging to a specific pathway category. |

Experimental Protocol: INTEGRATE Pipeline for Multi-Level Regulatory Analysis

This protocol is based on the INTEGRATE methodology for discerning metabolic and transcriptional control from multiomics data [28].

1. Data Preparation and Preprocessing * Transcriptomics Data: Obtain gene expression data (e.g., RNA-Seq) for the conditions under study. Perform standard normalization and differential expression analysis. * Metabolomics Data: Acquire targeted or untargeted intracellular metabolomics data for the same conditions. Ensure proper identification and quantification of metabolites. * Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM): Select a high-quality, context-appropriate GEM (e.g., RECON for human metabolism).

2. Data Integration into the Metabolic Model * Map Transcriptomics Data: Use Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) associations to convert gene expression values into a reaction expression score. * Map Metabolomics Data: Assign quantified intracellular metabolites to their corresponding species in the model.

3. Parallel Flux Prediction Analysis * Transcriptomics-Driven Flux Prediction: Use methods like E-Flux or a similar approach to predict potential flux distributions based on the reaction expression scores. * Metabolomics-Driven Flux Prediction: Utilize the metabolomics data to predict fluxes, for instance, by assuming a monotonic relationship between substrate concentration and reaction flux for low-abundance metabolites.

4. Identification of Regulatory Control * Intersect Predictions: Compare the flux predictions from the transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses. * Classify Reactions: * Metabolic Control: A significant flux change is predicted from metabolomics but not from transcriptomics. * Transcriptional Control: A significant flux change is predicted from transcriptomics but not from metabolomics. * Combined Control: Significant flux changes are predicted from both omics layers.

5. Validation * Validate predictions using direct flux measurements (e.g., 13C metabolic flux analysis) or through genetic/pharmacological perturbations.

Workflow Visualization: Multiomics Integration with INTEGRATE

This diagram illustrates the logical workflow of the INTEGRATE pipeline for characterizing multi-level metabolic regulation [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential databases, models, and software for multiomics metabolic modeling.

| Item Name | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) [28] [30] | Computational Model | Serves as a scaffold for integrating multiomics data; provides the stoichiometric network of metabolic reactions for a target organism. |

| Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) [3] [30] | Database | Provides reference information on metabolic pathways, genes, enzymes, and metabolites for model construction and validation. |

| MetaCyc Database [32] | Database | A curated database of metabolic pathways and enzymes used for functional profiling and pathway analysis. |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [29] [30] | Algorithm | A constraint-based modeling approach used to predict steady-state metabolic fluxes and optimize cellular objectives like growth. |

| Bayesian Factor Modeling [29] | Statistical Model | Used to infer hidden factors (like pathway activation states) and correlations from high-dimensional flux or expression data. |

| INTEGRATE Pipeline [28] | Software Pipeline | A specific computational tool that integrates transcriptomics and metabolomics data onto a GEM to disentangle metabolic and transcriptional regulation. |

What is the DBTL cycle and why is it crucial for strain development?

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle is a systematic framework used in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering to develop and optimize biological systems, such as microbial strains for producing biofuels, pharmaceuticals, and other valuable compounds [33]. This iterative process allows researchers to continuously refine genetic designs based on experimental data, significantly accelerating the development of efficient microbial cell factories [34].

FAQs: Common DBTL Cycle Challenges

Q: Our strain designs often fail during the Test phase. How can we improve initial design success? A: This common challenge often stems from incomplete understanding of host context. Implement machine learning (ML) tools that leverage existing multi-omics data to predict genetic part performance in your specific host chassis. Additionally, use automated design software that checks for compatibility issues like restriction enzyme sites and GC content before moving to the Build phase [35].

Q: The Learn phase is a bottleneck. How can we better translate experimental data into actionable insights? A: Integrate ML models specifically trained on your Test phase data. For metabolic engineering, employ algorithms that can identify relationships between genetic modifications and phenotypic outcomes from smaller datasets. Cloud-based bioinformatics platforms can help manage and analyze large multi-omics datasets more efficiently [1] [31].

Q: How can we manage the complexity of large combinatorial DNA libraries in the Build phase? A: Utilize automated workflow platforms that integrate with DNA synthesis providers and manage inventory. These systems can track thousands of variants simultaneously and generate assembly protocols compatible with high-throughput robotic systems, reducing errors and handling complexity [35].

Q: Our DBTL cycles take too long. What automation solutions are most impactful? A: Focus automation efforts on the most time-intensive steps: DNA assembly and functional assays. Automated liquid handlers for plasmid preparation combined with high-throughput screening systems like plate readers can dramatically increase throughput. Studies show that automated workflows can increase cloning throughput by 10-20x compared to manual methods [33] [35].

Machine Learning Integration in DBTL

ML Applications Across the DBTL Cycle

Machine learning transforms the DBTL cycle by enabling data-driven predictions and optimizations that would be impossible through manual analysis alone. Below are key applications:

Table 1: Machine Learning Applications in the DBTL Cycle

| DBTL Phase | ML Application | Key Benefit | Example Tools/Methods |