Resolving Underdetermined Systems in Flux Balance Analysis: Methods, Applications, and Validation for Biomedical Research

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a cornerstone constraint-based method for modeling metabolism in systems biology and metabolic engineering.

Resolving Underdetermined Systems in Flux Balance Analysis: Methods, Applications, and Validation for Biomedical Research

Abstract

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a cornerstone constraint-based method for modeling metabolism in systems biology and metabolic engineering. However, a fundamental challenge is that FBA problems are often underdetermined, with more unknown reaction rates than equations, leading to non-unique solutions. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on addressing this challenge. We explore the mathematical foundations of underdetermined systems, detail key methodological approaches like Flux Variability Analysis and parsimonious FBA to find optimal solutions, discuss troubleshooting strategies for infeasible scenarios, and review validation techniques to ensure model predictions are biologically relevant. By synthesizing current methodologies and validation frameworks, this resource aims to enhance the reliability and application of FBA in pinpointing drug targets and optimizing bioprocesses.

The Underdetermined Problem: Understanding the Mathematical Core of FBA

The Steady-State Assumption and the Stoichiometric Matrix

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the fundamental steady-state assumption in metabolic network analysis? The steady-state assumption posits that for any metabolite within a cellular system, the rate of production is balanced by the rate of consumption, leading to no net accumulation or depletion over time [1]. Mathematically, this is represented by the equation Sv = 0, where S is the stoichiometric matrix and v is the vector of metabolic fluxes [2] [3] [4]. This allows the analysis of metabolic fluxes without requiring knowledge of metabolite concentrations or enzyme kinetic parameters [3].

Why is the stoichiometric matrix central to Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)? The stoichiometric matrix is a mathematical representation of the metabolic network's structure [4]. Each row corresponds to a metabolite, and each column corresponds to a reaction. The entries are the stoichiometric coefficients of the metabolites in each reaction [3] [4]. This matrix enforces mass-balance constraints, defining the space of all possible, balanced flux distributions attainable by the network at steady state [2] [3].

My FBA problem is infeasible. What are the most common causes? Infeasibility occurs when the constraints imposed on the model—including the steady-state condition, reaction bounds, and any measured fluxes—cannot all be satisfied simultaneously [5]. Common causes include:

- Inconsistent Measured Fluxes: Experimentally measured flux values that violate the steady-state condition or other network constraints [5].

- Incorrectly Set Reaction Bounds: Setting irreversible reactions to carry negative flux or imposing upper and lower bounds that conflict with other constraints [2] [5].

- Conflicting Constraints: Additional linear constraints (e.g., on enzyme capacities) that are incompatible with the stoichiometry and other bounds [5].

How can I resolve an infeasible FBA problem? Systematic methods exist to identify and correct the minimal set of constraints causing infeasibility. Two primary approaches are:

- Linear Programming (LP) Method: Finds the minimal set of flux value corrections (e.g., to measured fluxes) to achieve feasibility [5].

- Quadratic Programming (QP) Method: Finds minimal corrections by minimizing the sum of squared deviations from the original flux values, often providing a more balanced solution [5]. The general workflow involves applying these algorithms to pinpoint inconsistent constraints or fluxes and adjusting them to restore feasibility.

Does the steady-state assumption prevent modeling growing or oscillating systems? No. The steady-state assumption can also be motivated from a long-term perspective, stating that no metabolite can accumulate or deplete indefinitely [1]. This perspective allows the assumption to be applied to oscillating and growing systems without requiring a quasi-steady-state at every time point. However, it is important to note that in such systems, the average metabolite concentrations may not be compatible with the average fluxes predicted by a standard steady-state model [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Diagnosing and Resolving an Infeasible FBA Problem

An infeasible model cannot find a flux distribution satisfying all constraints. This guide helps systematically identify and correct the issue.

Prerequisites:

- A metabolic model in a standard format (e.g., SBML).

- A linear programming solver (e.g., via the COBRA Toolbox).

- A list of constraints (bounds, measured fluxes) you have applied.

Protocol Steps:

- Verify Base Model Feasibility:

- Remove all user-defined constraints (e.g., measured flux values) and only keep the core constraints (steady-state, default reversibility).

- Perform FBA with a simple objective (e.g., ATP maintenance or biomass). If the model is feasible, proceed to Step 2. If not, the core model structure has errors (e.g., a reaction is incorrectly defined as irreversible).

Systematically Re-introduce Constraints:

- Add your custom constraints back into the model one by one or in small batches, checking for feasibility after each addition.

- This process will identify the specific constraint, or combination of constraints, that causes the infeasibility.

Apply a Feasibility Restoration Algorithm:

- Once the problematic constraints are identified, use an LP- or QP-based algorithm to find the minimal corrections required [5].

- For LP: The solution will suggest the smallest absolute changes to specific flux values.

- For QP: The solution will suggest changes that minimize the overall squared error, which often provides a more realistic distribution of corrections.

Interpret and Implement Corrections:

- Analyze the algorithm's output. Corrections suggested for experimentally measured fluxes may indicate measurement errors or context-specific model limitations.

- Update your constraint set with the corrected values and confirm the model is now feasible.

The logical workflow for this troubleshooting process is outlined below.

Guide: Handling Underdetermined Systems and Alternate Optimal Solutions

An underdetermined system has more unknown reaction fluxes than equations, leading to infinite possible flux distributions that satisfy Sv=0 [6] [3]. This guide helps characterize and analyze such systems.

Prerequisites:

- A feasible metabolic model.

- Software capable of Flux Variability Analysis (FVA).

Protocol Steps:

- Characterize System Determinacy:

- Let

mbe the number of metabolites (rows inS),nthe number of reactions (columns inS), andkthe number of fluxes with fixed values. - The number of unknown fluxes is

x = n - k. - The degrees of freedom are

x - rank(N_U), whereN_Uis the stoichiometric matrix for the unknown fluxes [5]. A positive value confirms an underdetermined system.

- Let

Perform Flux Variability Analysis (FVA):

- For the objective of interest (e.g., biomass maximization), first find the maximum value (

Z_max). - Then, for each reaction

v_iin the network:- Maximize

v_i, subject to Sv=0, bounds, andc^T v >= Z_max(or a fraction thereof). - Minimize

v_i, subject to the same constraints.

- Maximize

- This calculates the minimum and maximum possible flux for each reaction while still achieving a near-optimal objective.

- For the objective of interest (e.g., biomass maximization), first find the maximum value (

Identify Uniquely Determined Fluxes:

- Any reaction where the minimum and maximum flux from FVA are equal (or very close) is uniquely determined, even within the underdetermined system.

- Reactions with a range of possible fluxes are not uniquely determined.

Analyze Alternate Optimal Solutions:

- The FVA results reveal the network's flexibility. Pathways with non-zero flux ranges represent alternate routes the network can use to achieve the same optimal phenotypic state [3].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational and methodological "reagents" essential for working with steady-state models and FBA.

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Key Features / Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | Defines the network structure; encodes metabolite relationships in all metabolic reactions [3] [4]. | Sparse matrix (m metabolites x n reactions). Entries: negative for substrates, positive for products [4]. |

| Linear Programming (LP) Solver | Computes the optimal flux distribution by maximizing/minimizing a linear objective function subject to constraints [2] [3]. | Core computational engine for FBA. Solves max c^T v subject to Sv=0 and lb ≤ v ≤ ub [2]. |

| COBRA Toolbox | A MATLAB-based software suite for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) of metabolic models [3]. | Provides functions for FBA, FVA, gene deletion, and model creation. Reads/writes models in SBML format [3]. |

| Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) | Identifies the range of possible fluxes for each reaction while maintaining optimal (or near-optimal) objective function value [3]. | Quantifies network flexibility and identifies core vs. redundant metabolic routes. |

| Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) Rules | Boolean rules linking genes to the reactions they enable, allowing simulation of gene knockouts [2]. | Uses AND/OR logic (e.g., (Gene_A AND Gene_B) for a complex; (Gene_C OR Gene_D) for isozymes) [2]. |

Core FBA Workflow and Mathematical Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for setting up and solving an FBA problem, highlighting the interaction between the biological assumptions, mathematical constructs, and computational solution.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is an underdetermined system? An underdetermined system is a system of linear equations that has more unknown variables than equations. This means there are fewer constraints than degrees of freedom, leading to either no solution or infinitely many solutions rather than a single unique solution [7] [8].

How do underdetermined systems appear in Flux Balance Analysis? In FBA, the steady-state assumption creates a stoichiometric matrix where metabolites represent equations and metabolic fluxes represent unknowns. Since metabolic networks typically contain more reactions than metabolites, this naturally forms an underdetermined system [9] [10]. For example, a network might have 8 unknown fluxes but only 5 independent metabolite balance equations, resulting in 3 degrees of freedom [10].

What methods can resolve underdetermined systems in metabolic research? Researchers use several approaches: Flux Balance Analysis adds an biological objective function to select one optimal solution; Flux Variability Analysis identifies all possible flux ranges; sampling methods characterize the solution space; and experimental constraints from flux measurements reduce degrees of freedom [5] [10].

Why does my FBA model become infeasible when adding flux measurements? This occurs when the measured fluxes conflict with the stoichiometric, thermodynamic, or capacity constraints of the model. The system becomes overconstrained and no solution satisfies all requirements simultaneously [5].

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: FBA Model Has Infinite Solutions

Issue: Your FBA problem returns multiple optimal solutions rather than a unique flux distribution.

Solutions:

- Add regularization: Implement parsimonious FBA that minimizes total flux while maintaining optimal objective value

- Include additional constraints: Integrate transcriptomic, proteomic, or thermodynamic data to reduce feasible solution space

- Apply flux variability analysis: Determine the minimum and maximum possible flux through each reaction

- Use sampling methods: Characterize the solution space with uniform sampling of feasible flux distributions [10]

Problem: FBA Model Becomes Infeasible With Experimental Data

Issue: After incorporating measured flux data, your FBA model has no solution.

Solutions:

- Check measurement consistency: Verify that measured fluxes don't violate known network stoichiometry

- Identify conflicting constraints: Use linear programming to find the minimal set of flux measurements causing infeasibility [5]

- Apply reconciliation methods: Use quadratic programming to find minimal adjustments to measured fluxes that restore feasibility [5]

- Review network compression: Ensure dead reactions have been properly removed from the model

Problem: Unable to Determine All Fluxes Uniquely

Issue: Even with experimental constraints, some intracellular fluxes remain undetermined.

Solutions:

- Integrate 13C labeling data: Use isotopic tracer experiments to obtain additional constraints on internal fluxes

- Apply flux coupling analysis: Identify sets of reactions that must operate in fixed proportion

- Use most accurate fluxes algorithm: Iteratively determine fluxes based on accuracy measures [11]

- Implement elementary flux mode analysis: Decompose the solution into fundamental pathways [10]

Table 1: Characteristics of Underdetermined Systems in Metabolic Modeling

| Characteristic | Mathematical Definition | FBA Context | Typical Values in GSMMs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degrees of Freedom | Number of unknowns minus number of independent equations | Free flux variables | Hundreds to thousands in genome-scale models |

| Solution Space | Infinite solutions when consistent | Flux polyhedron | High-dimensional convex set |

| Determinacy | System is underdetermined when rank(A) < n | More reactions than metabolites | 2-3x more reactions than metabolites common |

| Redundancy | Linear dependencies between equations | Metabolite balances | Varies by network reconstruction |

Table 2: Methods for Resolving Underdetermined Systems in FBA

| Method | Approach | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis | Optimization with biological objective | Physiologically relevant, computationally efficient | Requires appropriate objective function |

| Flux Variability Analysis | Range analysis of feasible fluxes | Identifies possible flux ranges | Doesn't provide unique solution |

| Sampling Methods | Statistical characterization of solution space | Comprehensive view of possibilities | Computationally intensive for large networks |

| Experimental Constraints | Integration of measured fluxes | Grounds prediction in real data | Limited by measurement availability and accuracy |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Resolving Infeasible FBA Problems With Flux Measurements

Purpose: Identify and correct inconsistent flux measurements that cause FBA infeasibility [5].

Materials:

- Stoichiometric model (SBML format)

- Measured flux data

- Linear programming solver (e.g., COBRA Toolbox)

- Quadratic programming solver

Procedure:

- Formulate the base FBA problem with stoichiometric constraints and reaction bounds

- Add equality constraints for measured fluxes:

ri = fi, ∀ i ∈ F - Test feasibility of the constrained problem

- If infeasible, apply minimal correction algorithm:

- Linear programming: minimize sum of absolute corrections

- Quadratic programming: minimize sum of squared corrections

- Implement the corrected fluxes and verify feasibility

- Proceed with FBA using reconciled flux values

Validation: Confirm that corrected fluxes remain physiologically plausible and within experimental error ranges.

Protocol 2: Flux Variability Analysis for Underdetermined Systems

Purpose: Characterize the range of possible fluxes in an underdetermined metabolic network [10].

Materials:

- Stoichiometric model

- Defined environmental conditions

- Optimization software with LP capabilities

Procedure:

- Set up the metabolic model with appropriate constraints

- For each reaction in the network:

- Maximize the flux:

maximize vi subject to constraints - Minimize the flux:

minimize vi subject to constraints

- Maximize the flux:

- Record the minimum and maximum fluxes for each reaction

- Identify reactions with zero variability (must be determined)

- Calculate the variability index for each reaction:

(vmax - vmin)/vref

Interpretation: Reactions with small variability are well-constrained, while those with large variability require additional experimental data for precise determination.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Underdetermined Systems Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB-based FBA implementation | Solving underdetermined systems with optimization constraints |

| EFMtool | Elementary flux mode calculation | Pathway analysis of underdetermined networks |

| DFBAlab | Dynamic FBA simulation | Handling underdeterminacy in time-dependent systems |

| Sampling algorithms | Uniform sampling of solution space | Statistical characterization of flux distributions |

| LP/QP solvers | Optimization algorithms | Finding unique solutions to underdetermined problems |

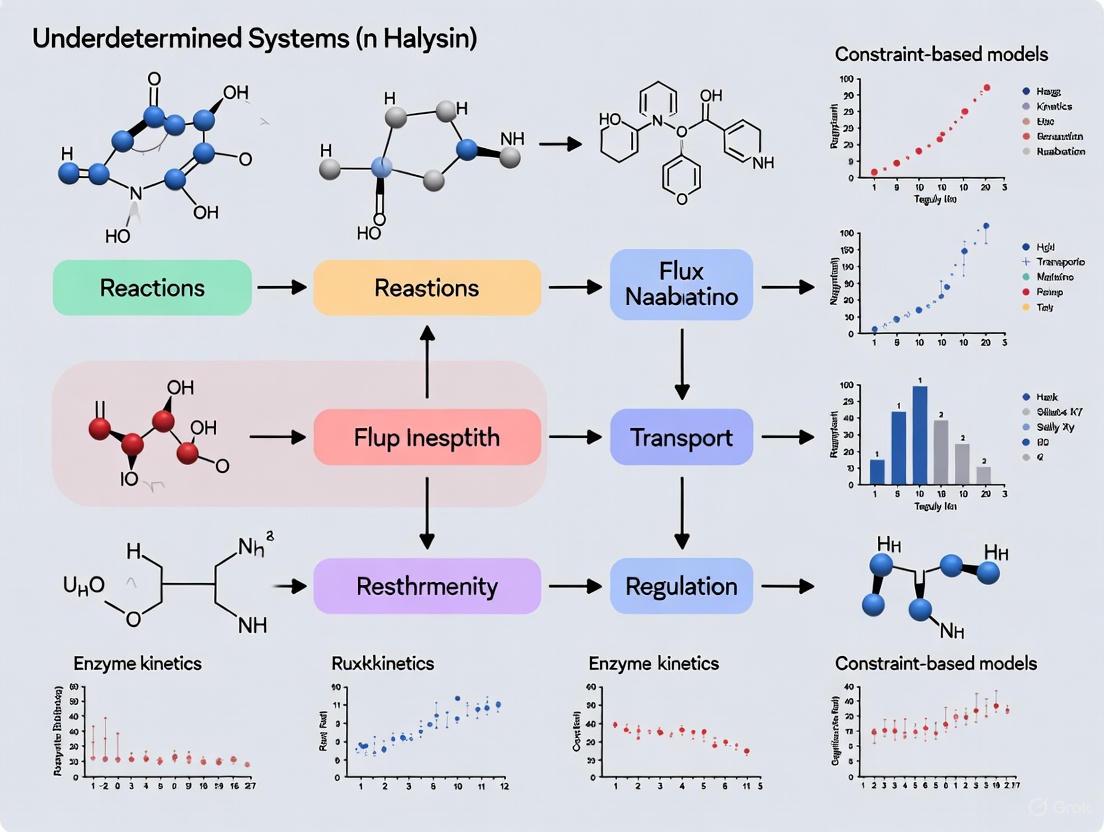

System Visualization

Underdetermined Systems Overview

FBA Resolution Workflow

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Q1: My Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) model produces multiple optimal flux distributions for the same objective (e.g., growth rate). How can I interpret this result?

A: This is a common scenario, indicating the presence of alternate optimal solutions [12]. Your model's solution space contains multiple flux vectors that achieve the same maximal objective value. This is not an error but a feature of underdetermined networks. To resolve this:

- Perform Flux Variability Analysis (FVA): Use this method to calculate the minimum and maximum possible flux through each reaction while still achieving the optimal objective value. This defines the boundaries of your flux polyhedron for the given objective [12].

- Identify Equivalent Reaction Sets: Analyze the network for redundancies—sets of reactions that can substitute for one another—which are a primary source of this variability [12].

Q2: How can I reduce the size of the feasible flux solution space to obtain more precise predictions?

A: The solution space (flux polyhedron) is large because the system is underdetermined. To constrain it further, you can:

- Integrate Transcriptomic Data: Incorporate gene expression data to constrain upper or lower flux bounds, effectively "turning off" reactions with zero expression.

- Apply (^{13})C-Metabolic Flux Analysis ((^{13})C-MFA): Use this experimental method to measure intracellular fluxes for a core metabolic network. These measured fluxes can then be used as additional constraints in your genome-scale model [13].

- Add Thermodynamic Constraints: Incorporate constraints based on reaction thermodynamics to eliminate flux directions that are not energetically feasible.

Q3: What is the best way to visualize the results of my flux analysis, such as the distribution of fluxes across a pathway?

A: Visualization is key to interpreting flux distributions. Several tools are designed specifically for this purpose:

- Pathway Projector: A tool that allows you to map your flux data onto metabolic pathways, providing a clear overview of metabolic activity [13].

- BioCyc Omics Viewer: Enables the visualization of high-throughput data, including metabolic fluxes, in the context of cellular pathways [13]. These tools help in understanding the quantitative flow through metabolic networks.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constraint-Based Flux Analysis using Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)

Objective: To predict an optimal, steady-state flux distribution that maximizes a biological objective (e.g., biomass growth) in a genome-scale metabolic model.

Methodology:

- Model Setup: Begin with a stoichiometric matrix (S) of your metabolic network, where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions.

- Define Constraints: Apply constraints to the system:

- Steady-state mass balance: S · v = 0, where v is the vector of reaction fluxes.

- Capacity constraints: α ≤ v ≤ β, where α and β are the lower and upper bounds for each reaction flux.

- Set Objective Function: Define a linear objective function to be maximized, typically the biomass reaction (Z = c(^T) · v).

- Solve the Linear Program (LP): Use linear programming to find the flux vector v that satisfies all constraints and maximizes the objective function [13] [12].

Protocol 2: (^{13})C-Metabolic Flux Analysis ((^{13})C-MFA) for Core Carbon Metabolism

Objective: To experimentally determine precise in vivo metabolic fluxes in the central carbon metabolism network.

Methodology:

- Tracer Experiment: Grow cells in a controlled bioreactor with a (^{13})C-labeled substrate (e.g., [1-(^{13})C]glucose).

- Steady-State Cultivation: Ensure the system reaches a metabolic and isotopic steady state.

- Mass Isotopomer Measurement: Harvest cells and measure the mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) of intracellular metabolites using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS).

- Flux Estimation: Use computational software to find the flux map that best fits the experimental MIDs by minimizing the difference between the simulated and measured labeling patterns [13].

Mandatory Visualization

Workflow for Flux Analysis of Underdetermined Networks

The Flux Polyhedron and Alternate Optima

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents and Materials for Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| (^{13})C-Labeled Substrates (e.g., [1-(^{13})C]Glucose) | Carbon source for tracer experiments; allows tracking of atom transitions through metabolic pathways to determine intracellular fluxes [13]. |

| Stoichiometric Metabolic Model | A computational matrix defining all metabolic reactions in the organism; the core constraint for defining the feasible flux solution space [13] [12]. |

| Linear/Quadratic Programming Solver | Software library (e.g., in Python or MATLAB) used to numerically solve the optimization problems in FBA and FVA [12]. |

| Flux Analysis Software | Computational tools (e.g., COBRA toolbox) used to perform FBA, (^{13})C-MFA, and Flux Variability Analysis [13]. |

| Pathway Visualization Tool | Software (e.g., Pathway Projector, BioCyc Omics Viewer) to map calculated flux distributions onto metabolic network diagrams for interpretation [13]. |

The Role of Linear Programming and Objective Functions

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental problem that Linear Programming solves in Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)?

FBA is used to simulate metabolism in cells. The core mathematical problem is that metabolic networks are underdetermined systems, meaning there are more unknown metabolic fluxes (reaction rates) than metabolite balance equations. This leads to a multitude of possible solutions [2] [3] [6]. Linear Programming (LP) resolves this by finding a single, optimal flux distribution that maximizes or minimizes a biological objective function, such as biomass production for simulating growth [2] [3].

2. Why is my FBA model infeasible, and how can I resolve it?

An FBA problem becomes infeasible when the constraints conflict, making it impossible to find a flux distribution that satisfies all of them simultaneously. A common cause is integrating known (e.g., measured) flux values that are inconsistent with the steady-state assumption or other model constraints [5].

Resolution Method: You can use algorithms that find the minimal corrections required to your input data to achieve feasibility. This can be formulated as either a Linear Programming (LP) or a Quadratic Programming (QP) problem, where the goal is to minimize the adjustments to the measured fluxes [5]. The general workflow is:

- Detect the inconsistency.

- Formulate an LP or QP to find minimal flux corrections.

- Solve the optimization problem.

- Apply the corrections and re-run the FBA.

3. How do I choose an appropriate objective function for my FBA simulation?

The objective function defines the biological goal the cell is presumed to be optimizing. The choice depends on your research context and the organism you are studying [3].

- Biomass Production: This is the standard objective for predicting growth rates and is commonly used for microorganisms like E. coli and yeast [2] [3].

- ATP Production: Used to simulate energy metabolism or maintenance [3].

- Production of a Specific Metabolite: In metabolic engineering, the objective can be set to maximize the synthesis rate of a biotechnologically important compound, such as succinic acid [2].

- Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment (MOMA): Used to predict fluxes in mutant strains by minimizing the distance from the wild-type flux distribution.

4. What is the difference between FBA and gap-filling, and what solvers are used?

FBA predicts fluxes in an existing metabolic network. Gap-filling is the process of adding missing reactions to a draft metabolic model to enable it to produce biomass on a specified growth medium [14].

- Solver: KBase, for instance, uses the SCIP solver for its gap-filling algorithm, which can handle complex problems involving integer variables [14]. For pure linear optimizations in standard FBA, solvers like GLPK are also commonly used [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Infeasible FBA Problem

Problem: The FBA simulation fails because the linear program (LP) is infeasible. This often occurs after integrating measured flux data [5].

Diagnosis:

- Verify that the measured flux values are consistent with the network stoichiometry.

- Check for conflicts between new flux constraints and pre-existing bounds on reactions (e.g., reversibility).

Resolution Protocol: The following methodology resolves infeasibilities by making minimal adjustments to measured fluxes [5].

Workflow for Resolving Infeasible FBA

Formulate the Correction Problem:

- Let

v_measuredbe the vector of measured fluxes. - Introduce a correction vector,

δ, for these fluxes. - The new constraint becomes:

v = v_measured + δ. - The objective is to minimize the total correction. This can be done via:

- LP Formulation: Minimize the sum of absolute values of

δ(can be implemented using auxiliary variables). - QP Formulation: Minimize the sum of squares of

δ(minimizes large adjustments).

- LP Formulation: Minimize the sum of absolute values of

- Let

Solve the Problem: Use an appropriate LP (e.g., GLPK) or QP solver to find the optimal

δ.Apply and Validate: Update the model constraints with the corrected fluxes

(v_measured + δ)and re-run the original FBA to confirm feasibility.

Issue 2: Non-Unique or Underdetermined Flux Solution

Problem: The FBA solution is not unique; multiple flux distributions yield the same optimal objective value [6].

Diagnosis: This is a fundamental property of large, underdetermined metabolic networks. Even with an objective function, many fluxes may not be uniquely determined [2] [6].

Resolution Protocol: Method: Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) FVA characterizes the solution space by calculating the minimum and maximum possible flux for each reaction while maintaining the optimal objective value [3].

Procedure:

- First, run standard FBA to find the optimal value of the objective function,

Z_opt. - For each reaction

iin the model: a. Maximize the fluxv_i, subject to: *S • v = 0*lb ≤ v ≤ ub*c^T • v = Z_opt(constrain the objective to its optimal value) b. Minimize the fluxv_i, subject to the same constraints. - The results provide the range of possible fluxes

[v_i_min, v_i_max]for each reaction within the optimal solution space. Reactions withv_i_min ≈ v_i_maxare uniquely determined.

Issue 3: Model Fails to Produce Biomass (Gap-Filling)

Problem: A genome-scale metabolic model, often derived from genomic annotations, is unable to produce biomass on a medium where the organism is known to grow. This indicates "gaps" in the network [14].

Diagnosis: The draft model lacks essential reactions, frequently transporters or key metabolic steps, due to missing or inconsistent annotations [14].

Resolution Protocol: Method: Gap-filling using Linear Programming.

Gap-filling Process with LP

- Define the Context: Specify the growth medium (available nutrients) in the model constraints [14].

- Formulate the LP:

- The model includes reactions from the draft reconstruction plus a database of candidate reactions that can be added.

- Each candidate reaction is assigned a "cost" (e.g., higher cost for non-native or transporter reactions to penalize their addition).

- The objective function is to minimize the total weighted flux through the added candidate reactions, effectively finding the smallest set of reactions that enable growth [14].

- The key constraint is that the biomass flux must be greater than zero.

- Solve and Integrate: Solve the LP and add the set of reactions from the solution to your model [14].

- Manual Curation: The gap-filling solution is a prediction and requires manual biological validation and curation [14].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key computational tools and concepts essential for working with FBA.

| Item/Concept | Function in FBA Research |

|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | The core mathematical representation of the metabolic network. Each element Sij is the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j [2] [3]. |

| Linear Programming (LP) Solver (e.g., GLPK) | Software that performs the optimization calculation to find the flux distribution that maximizes the objective function subject to constraints [14]. |

| COBRA Toolbox | A widely used MATLAB toolbox for performing constraint-based research, including FBA and related methods [3]. |

| Objective Function Vector (c) | A vector that defines the biological objective (e.g., growth). It typically contains zeros except for a '1' at the position of the reaction to be optimized [2] [3]. |

| Flux Bounds (lb, ub) | Constraints that define the minimum and maximum allowable flux for each reaction, encoding reaction reversibility and uptake rates [2] [5]. |

| Biomass Reaction | A pseudo-reaction that drains biomass precursor metabolites at their cellular ratios. Its flux represents the growth rate of the organism [2] [3]. |

The table below summarizes the different linear programming formulations used to address common challenges in FBA.

| Problem Type | Objective Function | Key Constraints | Outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard FBA [2] [3] | Maximize c^T • v (e.g., biomass) |

S • v = 0lb ≤ v ≤ ub |

Predicts a single, optimal flux distribution for growth. | ||

| Resolving Infeasibility [5] | Minimize `∑ | δ | ` | S • v = 0lb ≤ v ≤ ubv_f = v_measured + δ |

Finds minimal corrections to measured fluxes to make the model feasible. |

| Gap-Filling [14] | Minimize ∑ (cost • v_added) |

S • v = 0lb ≤ v ≤ ubv_biomass > 0 |

Identifies a minimal set of reactions to add to the model to enable growth. | ||

| Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) [3] | Maximize/Minimize each v_i |

S • v = 0lb ≤ v ≤ ubc^T • v = Z_opt |

Determines the permissible range of each flux within the optimal solution space. |

Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) Rules and Network Connectivity

FAQs: GPR Rules and Network Connectivity

Q1: What are Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) rules and why are they critical in Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)?

GPR rules are logical Boolean expressions that explicitly connect genes to the metabolic reactions they enable within a genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) [9] [15]. They are fundamental to FBA because they translate genetic information into functional metabolic constraints. A GPR rule specifies whether a reaction requires a single gene, multiple protein subunits (encoded by different genes) that assemble into a functional enzyme (using the AND operator), or multiple isozymes (encoded by different genes) that can each catalyze the same reaction independently (using the OR operator) [9] [15]. This mapping allows researchers to simulate genetic perturbations, such as gene deletions, by constraining the associated reaction fluxes to zero, thereby predicting the phenotypic outcome on growth or metabolite production [9] [16].

Q2: During a gene deletion study, my FBA simulation predicts no growth, but experimental data shows the mutant strain survives. What are the potential causes related to GPR rules and network connectivity?

This discrepancy can arise from several sources related to model incompleteness or incorrect GPR logic:

- Incorrect GPR Boolean Logic: The GPR rule for the reaction may inaccurately represent the biological system. For example, an essential reaction might be incorrectly annotated as requiring two gene products with an AND relationship when, in reality, an isozyme (OR relationship) exists that can compensate for the loss [9] [15].

- Missing Alternative Pathways: The model's metabolic network may be incomplete. An alternative pathway that is not captured in the model could be active in the real organism, bypassing the blocked reaction [9] [17].

- Suboptimal Behavior of Mutants: FBA typically assumes that deletion strains optimize the same objective (e.g., growth rate) as the wild type. In reality, knockout mutants may adopt suboptimal survival strategies or different metabolic objectives that are not modeled [17].

- Inaccurate Biomass Composition: The model's biomass objective function, which defines the stoichiometric requirements for growth, may not accurately reflect the actual composition of the mutant strain under the specific environmental condition [9].

Q3: How can I automatically reconstruct or validate GPR rules for a new organism?

Manual curation of GPR rules is time-consuming. Automated tools like GPRuler can reconstruct GPR rules by mining multiple biological databases [15]. The pipeline can start from just the name of a target organism or an existing metabolic model without GPR rules. It queries databases such as MetaCyc, KEGG, Rhea, ChEBI, TCDB, and the Complex Portal (which provides crucial information on protein-protein interactions and complexes) to establish the logical relationships between genes, proteins, and reactions [15]. The performance of such tools has been shown to reproduce original GPR rules with high accuracy and, in some cases, even correct existing errors in manually curated models [15].

Q4: How does network connectivity influence the prediction of gene essentiality?

The structure of the metabolic network is a key determinant of gene essentiality. A reaction is more likely to be essential if it is the only link in a pathway that produces a critical biomass precursor. However, high network connectivity and redundancy (e.g., through parallel pathways or isozymes) can provide robustness, making genes non-essential. Advanced methods now integrate graph neural networks with FBA to better capture these topological properties. These approaches represent the metabolic network as a graph and use machine learning to predict how perturbations (like gene deletions) propagate through the connected system, often improving prediction accuracy over FBA alone [17] [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Discrepancies Between Predicted and Experimental Gene Essentiality

Problem: Your FBA simulation identifies a gene as essential (predicted growth = 0), but laboratory experiments show the knockout mutant is viable.

Investigation Protocol:

Verify the GPR Rule:

- Action: Examine the Boolean logic of the GPR rule associated with the deleted gene.

- Check for AND/OR logic errors. An AND rule means all gene products are necessary for the reaction; an OR rule means any single gene product is sufficient [9].

- Consult primary literature and databases like UniProt and Complex Portal to validate the protein complex or isozyme structure [15].

Check for Network Gaps and Redundancy:

- Action: Manually inspect the metabolic pathway where the reaction is located.

- Look for known alternative pathways or isozymes in biochemical databases (e.g., KEGG, MetaCyc) that might not be present in your model [15].

- Use FBA to test if providing a known missing metabolite (a potential bypass) restores growth in silico.

Re-examine the Biomass Objective Function:

- Action: Review the composition of your model's biomass reaction.

- Ensure the biomass formulation is appropriate for your specific experimental condition (e.g., aerobic vs. anaerobic). An incorrect biomass objective is a common source of error [9].

Simulate Suboptimal Mutant Behavior:

- Action: If using standard FBA, consider algorithms that do not assume optimal growth for the mutant, such as MoMA (Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment), which can sometimes provide better predictions for mutant phenotypes [17].

Guide 2: Correcting GPR Rule Annotation Errors

Problem: A GPR rule in your model is suspected to be incorrect, leading to faulty gene deletion predictions.

Validation and Correction Methodology:

Data Mining with Automated Tools:

- Action: Input your model or organism name into an automated GPR reconstruction tool like GPRuler [15].

- Compare the tool's proposed GPR rules with your model's existing rules. Mismatches indicate areas requiring manual curation.

Manual Curation from Multiple Sources:

- Action: Systematically gather evidence from high-quality databases.

- UniProt: Check for information on protein complexes and isoforms [15].

- Complex Portal: Use this resource to find experimentally determined protein complex structures [15].

- KEGG ORTHOLOGY & BRITE: Investigate conserved protein complex modules across species [15].

- Literature Search: Use published experimental studies (e.g., enzyme assays, co-immunoprecipitation) as the highest form of evidence.

Incorporate and Test the New Rule:

- Action: Update the GPR rule in your model.

- Re-run the gene deletion simulation. A corrected OR rule, for instance, should show growth if an alternative isozyme is present.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational tools and resources essential for working with GPR rules and metabolic networks.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for GPR and Metabolic Network Analysis

| Item Name | Function/Application | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| GPRuler | Automated reconstruction of GPR rules. | An open-source Python tool that mines multiple databases (MetaCyc, KEGG, Complex Portal) to automatically generate Boolean GPR rules for metabolic models, minimizing manual effort [15]. |

| COBRA Toolbox | Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis. | A MATLAB suite that provides standard functions for performing FBA, gene deletion studies, and other analyses on genome-scale metabolic models, including those with GPR rules [9]. |

| MetNetComp / gDel_minRN | Database and algorithm for gene deletion strategies. | A web-based platform that curates thousands of pre-computed gene deletion strategies for growth-coupled production. The gDel_minRN algorithm finds minimal gene sets to knock out [18]. |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Predicting metabolic phenotypes. | A mathematical optimization technique used to simulate metabolism by calculating steady-state reaction fluxes (S∙v = 0) that maximize an objective (e.g., biomass). It is the foundation for in silico gene essentiality prediction [9] [16]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (e.g., FlowGAT, GraphGDel) | Predicting gene essentiality from network structure. | Machine learning frameworks that combine FBA solutions with graph-based representations of metabolism to improve the prediction of gene essentiality by learning from the network's connectivity [17] [18]. |

Experimental Protocol: Predicting Gene Essentiality Using FBA

This protocol details the steps for performing an in silico single-gene deletion study using Flux Balance Analysis to predict gene essentiality.

Objective: To identify metabolic genes that are essential for growth under defined environmental conditions.

Principle: The model is constrained to simulate the absence of a gene. If the GPR rule evaluates to false, the associated reaction(s) are forced to carry zero flux. The model then attempts to maximize the growth rate. A gene is predicted as essential if the maximum possible growth rate is zero or falls below a defined threshold [9].

Procedure:

- Load the Model: Import a genome-scale metabolic reconstruction that includes GPR rules. Ensure the model is functional and can produce biomass under your baseline condition (e.g., complete medium with glucose) [9].

- Define the Environmental Constraints: Set the exchange reaction bounds to reflect the experimental growth medium (e.g., lower and upper bounds for glucose, oxygen, and other nutrients) [9].

- Set the Fitness Objective: Define the biomass reaction as the objective function to be maximized [9] [16].

- Perform Wild-Type Simulation: Solve the FBA problem for the wild-type strain to establish a reference growth rate [9].

- Iterative Gene Deletion:

- For each gene in the model, computationally "delete" it by evaluating its GPR rule. If the rule evaluates to false, constrain the flux through all reactions associated with that gene to zero [9].

- Solve the FBA problem again to find the maximum achievable growth rate with the gene deleted.

- Classify Gene Essentiality:

- Compare the mutant growth rate to the wild-type growth rate.

- A gene is typically classified as essential if the predicted growth rate is below a small threshold (e.g., < 1% of wild-type growth) or zero [9].

Expected Output: A list of genes classified as either essential or non-essential for growth in the specified condition.

Logical Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

GPR Rule Evaluation Logic

The following diagram illustrates the logical process a constraint-based model follows to determine reaction activity based on GPR rules during a gene deletion simulation.

FBA and GPR Integration Workflow

This diagram outlines the overall integration of GPR rules into the FBA framework for a gene essentiality screen, connecting the logical evaluation to the mathematical simulation.

Solving for Solutions: Key Algorithms and Practical Applications in Biomedicine

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) and why is it necessary after performing Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)?

FVA is a constraint-based modeling technique used to determine the minimum and maximum possible flux value that each reaction in a metabolic network can carry while still satisfying all model constraints and maintaining a specified level of optimality for a biological objective, such as biomass production [19] [20]. It is necessary because the solution to an FBA problem is often highly degenerate, meaning multiple flux distributions can achieve the same optimal objective value [19] [3]. FVA characterizes this full range of possible optimal solutions, thereby revealing the metabolic flexibility of the network [21] [20].

Q2: My FVA computation is slow, especially for large models. How can I accelerate it?

Performance issues with FVA are common due to its computational intensity. Several acceleration techniques are available:

- Use High-Performance Implementations: Opt for specialized implementations like

fastFVAorVFFVA(Very Fast Flux Variability Analysis), which are designed for efficiency and can leverage parallel computing [22] [20]. - Enable Dynamic Load Balancing: Standard parallel implementations statically assign reactions to cores. Tools like

VFFVAuse dynamic load balancing to ensure all CPU cores are utilized efficiently, which is particularly beneficial for ill-conditioned models and can lead to a speedup factor of up to 100 [22]. - Employ Heuristics: The COBRA Toolbox offers heuristic levels that can pre-identify reactions that hit their flux bounds without solving an optimization problem for each one, significantly reducing the number of linear programs (LPs) that need to be solved [20]. One proposed algorithm uses solution inspection to reduce the number of LPs required, thus shortening the computation time [19].

- Utilize Efficient Solvers: Use solvers like CPLEX through their dedicated APIs (e.g., in

fastFVAorVFFVA) for faster performance compared to more generic interfaces [22] [20].

Q3: What are thermodynamically infeasible loops, and how can I prevent them in my FVA results?

Thermodically infeasible loops, or internal cycles, are network sub-cycles that can generate energy or metabolites without any net input, representing biologically unrealistic scenarios [21]. These loops can make the internal flux distribution of models unreliable [21]. To eliminate them, you can perform loopless FVA [20]. In the COBRA Toolbox, this is achieved by setting the allowLoops parameter to false when running the fluxVariability function, which applies additional constraints to remove thermodynamically infeasible solutions from the flux ranges [20].

Q4: How can I reduce the size of the solution space to get more precise flux predictions?

A large solution space with many variable reactions can lead to biologically unrealistic phenotypes [21]. To constrain the solution space, you can integrate experimental data as additional constraints to your model [21]. Effective data types include:

- Metabolic Data: Incorporate measured uptake and secretion rates of metabolites from the growth medium [21].

- Gene Essentiality Data: Set the flux of reactions to zero for genes that have been experimentally shown to be non-essential [21].

- Proteomic Data: Use enzyme abundance measurements to constrain the upper bounds of their corresponding reaction fluxes [21]. Studies have shown that step-wise integration of such data progressively reduces the number of reactions with variable fluxes, leading to a more robust and realistic solution space [21].

Q5: What is the difference between the various FVA implementations in the COBRA Toolbox?

The COBRA Toolbox provides several FVA implementations, each with different advantages [20]. The table below summarizes the key differences for selection.

| Implementation | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|

fluxVariability |

Most flexible; supports all options (e.g., loopless FVA, flux distributions). | Can be slow for large-scale metabolic models [20]. |

fastFVA |

High performance; advanced parallelization strategies [22] [20]. | Requires the CPLEX solver; has limited support for loopless FVA [20]. |

mtFVA |

Very high performance using a multi-threaded architecture [20]. | Requires CPLEX; offers no loopless support or flux distribution computation [20]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Performance and Computational Issues

Problem: FVA calculations are taking an excessively long time or running out of memory.

| Possible Cause | Solution | Relevant Protocol/Resource |

|---|---|---|

| Large Model Size | Use a high-performance implementation like VFFVA or fastFVA. |

Protocol: Configure VFFVA with dynamic load balancing using MPI and OpenMP for HPC clusters [22]. |

| Ill-conditioned Problems | Disable solver scaling to handle numerical instabilities. For VFFVA with CPLEX, set the SCAIND parameter to -1 [22]. |

Protocol: Use solver-specific parameters to fine-tune performance, such as setting PARALLELMODE=1 and THREADS=1 in CPLEX [22]. |

| Inefficient Parallelization | Ensure dynamic load balancing is active to prevent CPU cores from sitting idle while others process difficult LPs [22]. | Resource: The VFFVA software, available in C, MATLAB, and Python from its GitHub repository [22]. |

| Too many LPs solved | Activate heuristics in the COBRA Toolbox to pre-identify bounded reactions. | Protocol: In fluxVariability, set the heuristics parameter to level 1 or 2 to reduce the number of LPs that need to be solved [20]. |

Biological Interpretation Issues

Problem: The calculated flux ranges are too wide or suggest biologically impossible scenarios.

| Possible Cause | Solution | Relevant Protocol/Resource |

|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamically Infeasible Loops | Execute a loopless FVA. | Protocol: In the COBRA Toolbox, call fluxVariability with the parameter 'allowLoops', false [20]. |

| Insufficient Model Constraints | Integrate experimental data (e.g., metabolomics, proteomics) to further constrain the model's flux bounds [21]. | Protocol: Use the changeRxnBounds function in the COBRA Toolbox to update reaction constraints based on experimental measurements [3]. |

| Uncertainty in the Optimal Objective | Perform FVA at a sub-optimal objective level. This explores flux ranges that support near-optimal growth, which may be more biologically relevant. | Protocol: Set the optPercentage parameter to a value less than 100 (e.g., 99) to require only 99% of the optimal objective value [20]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standard FVA Workflow Using the COBRA Toolbox

This protocol outlines the steps to perform a basic FVA using the COBRA Toolbox's fluxVariability function.

1. Prerequisite: Perform FBA

- First, solve a Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) problem to find the optimal objective value (e.g., maximal growth rate) for your model [3] [20].

2. Configure and Run FVA

- Use the

fluxVariabilityfunction to compute the minimum and maximum flux for each reaction while requiring 100% (or a specified percentage) of the optimal objective [20].

3. Analyze Results

- The outputs

minFluxandmaxFluxare vectors containing the flux range for each reaction. Reactions with a small difference between min and max flux are considered tightly constrained, while those with a large range are flexible [21] [20].

The following diagram illustrates this standard FVA workflow and its role in characterizing the solution space of a metabolic model.

Protocol for Inspecting the Solution Space via Random Sampling

This method, inspired by research, helps investigate the robustness of FBA solutions and the variance of biological phenotypes by exploring alternate optimal flux distributions [21].

1. Determine Variable Reactions with FVA

- Perform an initial FVA. Identify all "variable" reactions, defined as those with a flux range larger than a chosen threshold (e.g., > 1x10⁻⁶) [21].

2. Generate Perturbed Flux Distributions

- For each variable reaction, fix its flux to several (e.g., 10) randomly selected values within its FVA-determined range [21].

- For each set of fixed fluxes, resolve the FBA problem. This generates a multitude of different optimal flux distributions.

3. Analyze Phenotypic Robustness

- Analyze the resulting flux distributions to see how sensitive the overall network phenotype is to changes in the variable reactions. This can reveal branching points where the model's behavior is highly sensitive and help prevent wrong conclusions based on a single FBA solution [21].

The logical flow of this solution space inspection protocol is shown below.

The following table details key software tools and resources essential for conducting effective FVA.

| Tool/Resource | Function | Usage Note |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox [3] [20] | A MATLAB-based suite providing the primary fluxVariability function and other constraint-based analysis methods. |

The most flexible environment for most FVA applications, including loopless FVA. |

| VFFVA [22] | A standalone, high-performance C implementation of FVA with dynamic load balancing. | Ideal for very large models or when maximum computational speed is required on HPC systems. |

| fastFVA [22] [20] | A C implementation packaged as a MEX file for the COBRA Toolbox, optimized for use with CPLEX. | A strong balance of performance and integration within the COBRA ecosystem. |

| CPLEX Optimizer | A commercial-grade, high-performance mathematical programming solver. | Using CPLEX (e.g., with fastFVA or VFFVA) can drastically reduce computation time compared to free solvers [22]. |

| Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | The core mathematical representation of the metabolic network, defining mass balance constraints [3]. | The quality and completeness of the model reconstruction directly determines the biological relevance of FVA results. |

The Problem of Underdetermined Systems in FBA

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a constraint-based modeling approach that uses mathematical constraints to predict optimal flux distributions in metabolic networks without needing detailed kinetic information [23]. A fundamental challenge in FBA is that metabolic networks are typically underdetermined, meaning there are more reactions than metabolites. This leads to multiple flux distributions that satisfy all constraints (steady-state mass balance, reaction bounds) while achieving the same optimal objective value (e.g., maximal biomass production) [23]. Consequently, standard FBA fails to provide a unique solution, complicating biological interpretation and experimental validation.

The pFBA Principle: Energy Efficiency as a Biological Objective

Parsimonious FBA (pFBA) addresses this limitation by introducing a secondary optimization criterion. After identifying an optimal growth rate or other primary objective, pFBA finds the flux distribution that achieves this objective while minimizing the total sum of absolute flux values throughout the network [23]. This principle is grounded in the biological hypothesis that cells have evolved to achieve metabolic objectives efficiently, minimizing protein cost and energy expenditure [23]. By selecting the most energy-efficient pathway among multiple alternatives, pFBA provides a unique, biologically realistic flux solution.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: My pFBA solution shows non-zero fluxes for apparently irrelevant reactions. What could be causing this?

- Incorrect Reaction Bounds: Check the lower and upper bounds (

lb,ub) for all reactions in your model. Ensure that reversible reactions have appropriate negative lower bounds and that irreversible reactions have a lower bound of zero. Incorrect bounds can force flux through unnecessary cycles. - Network Gaps: Search for and eliminate thermodynamically infeasible cycles (EFCs) that can carry flux without any net change in metabolites. Using a method called CycleFreeFlux might be necessary as a subsequent step.

- Overly Stringent Primary Objective: Verify that the primary objective (e.g., biomass) is indeed at its maximum. If the constraint is too tight, it might force flux through inefficient routes.

Q2: How does pFBA handle uncertainty in the biomass composition, which is a common issue in FBA?

- pFBA is sensitive to variations in the biomass equation, as the primary solution it refines is based on this objective [24]. If the macromolecular composition (e.g., protein, RNA, lipid ratios) is inaccurate or varies significantly with environmental conditions, the "optimal" solution from the first step will be flawed.

- Solution: Consider using an ensemble representation of the biomass equation to account for natural variation in cellular constituents [24]. This approach, known as FBAwEB (FBA with Ensemble Biomass), can mitigate inaccuracies arising from a single, fixed biomass composition.

Q3: The pFBA solution is unique for the given model and constraints, but how can I validate it against experimental data?

- Compare with (^{13}\text{C}) Metabolic Flux Analysis ((^{13}\text{C})-MFA): This is the gold standard for experimental validation of intracellular fluxes. Compare your pFBA-predicted central carbon metabolism fluxes with those measured via (^{13}\text{C}) tracing experiments [23].

- Integrate with Omics Data: Use transcriptomic or proteomic data to create context-specific models. Reactions associated with non-expressed genes can be down-weighted or constrained, which can bring pFBA predictions closer to measured physiological states [25].

- Gene Essentiality Predictions: Test if your pFBA model correctly predicts which gene knockouts will inhibit growth. A good model should accurately identify essential metabolic genes.

Q4: When should I use pFBA over other FBA variants like FVA (Flux Variability Analysis)?

- Use pFBA when you need a single, unique, and physiologically realistic flux map for analysis, such as predicting the primary metabolic state under a given condition or for generating inputs for machine learning algorithms [25].

- Use FVA when you want to understand the flexibility of the metabolic network. FVA calculates the minimum and maximum possible flux for each reaction while maintaining the optimal objective. This is useful for identifying alternative pathways and reactions with rigid flux requirements.

Experimental & Computational Protocols

Core Protocol for Implementing pFBA

The following workflow outlines the standard procedure for performing a pFBA simulation. This diagram summarizes the two-stage optimization process:

Detailed Steps:

Perform Standard FBA:

- Objective: Maximize the biomass reaction (

v_biomass). - Mathematical Formulation:

- Maximize ( Z = c^T \cdot v )

- Subject to:

- ( S \cdot v = 0 ) (Mass balance constraint)

- ( \alphai \leq vi \leq \beta_i ) (Flux capacity constraints)

- Output: The maximum theoretical growth rate, ( v_{biomass}^{max} ).

- Objective: Maximize the biomass reaction (

Implement pFBA:

- Objective: Minimize the sum of absolute values of all metabolic fluxes (( \sum |v_i| )), representing total enzyme investment.

- Add a Constraint: Fix the biomass flux to the value found in Step 1 (( v{biomass} = v{biomass}^{max} )).

- Mathematical Formulation (as a Linear Program):

- Minimize ( \sum |vi| )

- Subject to:

- ( S \cdot v = 0 )

- ( \alphai \leq vi \leq \betai )

- ( v{biomass} = v{biomass}^{max} )

- Note: The absolute value is handled by splitting each flux ( v_i ) into positive and negative components (( v_i = v_i^+ - v_i^- )) and minimizing the sum ( v_i^+ + v_i^- ).

- Output: A unique flux vector

v_pfbathat achieves maximum growth with minimal total flux.

Protocol for Integrating Transcriptomic Data with pFBA

This advanced protocol uses gene expression data to create more context-specific flux predictions [25].

Detailed Steps:

Data Preparation:

- Obtain transcriptomic data (e.g., RNA-Seq) for your condition of interest.

- Normalize the data (e.g., RPKM, TPM).

- Calculate fold changes relative to a control condition (e.g., minimal medium) by dividing the RPKM values for experimental conditions by the average RPKM of the controls. This centers the data around 1, facilitating integration [25].

Model Contextualization:

- Map gene expression data onto model reactions using gene-protein-reaction (GPR) rules.

- Use methods like E-Flux or a parsimonious enzyme usage framework to translate gene fold changes into constraints on the upper and lower bounds of the corresponding reactions. Reactions associated with lowly expressed genes will have their maximum allowed flux reduced.

Execution and Analysis:

- Run the core pFBA protocol (Section 3.1) on the constrained model.

- The resulting flux distribution will reflect both the optimal growth principle and the transcriptomic state of the cell.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key materials and tools required for conducting pFBA and related analyses.

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Use Case in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) | A mathematical representation of all known metabolic reactions in an organism. Serves as the core framework for FBA/pFBA. | Required for all protocols. Formats include .xml (SBML) or .mat (MATLAB). |

| Linear Programming (LP) Solver | Software that performs the numerical optimization (e.g., Gurobi, CPLEX, COIN-OR). | Essential for solving both the FBA (maximization) and pFBA (minimization) problems. |

| COBRA Toolbox | A MATLAB-based software suite for constraint-based modeling. Contains built-in functions for FBA and pFBA. | Simplifies the implementation of the core pFBA protocol and integration with other analysis tools. |

| Transcriptomic Dataset | Gene expression data (e.g., RNA-Seq) quantifying mRNA levels under specific conditions. | Used to create context-specific models in the advanced protocol (Section 3.2). Data is often in RPKM or TPM format [25]. |

| Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | A mathematical matrix where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions. Entries are stoichiometric coefficients. | The core of the model, used to formulate the mass balance constraint ( S \cdot v = 0 ). |

Advanced Integrations and Future Directions

Combining pFBA with Machine Learning

Machine learning (ML) can be used to analyze high-dimensional output from pFBA simulations across many conditions. Key applications include:

- Dimensionality Reduction: Techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) can reduce the complexity of pFBA-predicted flux distributions, helping to identify key metabolic differences between conditions [25] [26].

- Feature Selection: Algorithms such as LASSO regression can identify the most important transcripts or fluxes that predict a particular phenotypic outcome, linking gene expression to metabolic function [25] [26].

Dynamic and Multi-Objective Extensions

- Dynamic FBA (dFBA): pFBA can be incorporated into dFBA frameworks to simulate time-course experiments, providing unique flux solutions at each time point. Recent models, like the Integrated Multiphasic Continuous (IMC) model, hypothesize that cells adapt their FBA objective over time during processes like batch fermentation [27].

- Inverse FBA (invFBA): This approach infers the likely cellular objective function from measured flux data. pFBA-generated fluxes can serve as inputs for invFBA to test hypotheses about cellular goals beyond growth maximization [28].

Geometric FBA and Flux Sampling for Solution Space Exploration

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the core challenges of underdetermined systems in FBA, and what methods address them? Underdetermined systems in FBA arise when the stoichiometric constraints and other model conditions define a solution space with infinitely many feasible flux distributions, rather than a single, unique solution [10]. This occurs because the number of metabolic reactions typically exceeds the number of metabolites, leaving degrees of freedom [10]. Core challenges include:

- Non-Unique Solutions: Standard FBA returns a single, often extreme, flux vector, failing to represent the full range of possible metabolic states [29].

- Computational Intensity: Enumerating all possible states via Elementary Flux Modes (EFMs) becomes computationally prohibitive for genome-scale models due to a combinatorial explosion in their number [29] [10].

- Uninformative Bounds: Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) calculates the min/max range for each flux but produces a high-dimensional bounding box that occupies a negligible fraction of the actual solution space, offering limited insight [29].

Methods to address these challenges include:

- Geometric FBA: Finds a unique, central flux vector within the solution space that is in some sense "central" or "balanced" [30].

- Flux Sampling: Uses algorithms like OptGP or ACHR to generate a statistically representative set of flux distributions from the solution space, allowing for analysis of flux correlations and variances [31].

- Solution Space Kernel (SSK): Characterizes the solution space by identifying a low-dimensional, bounded kernel and a set of rays for unbounded directions, providing a manageable geometric description [29].

FAQ 2: My flux sampling results seem biased or do not cover the expected phenotypic range. How can I improve them? This common issue often occurs because default sampling parameters may not adequately explore the phenotypic range of key fluxes, such as substrate uptake, growth, or product secretion [31]. The following troubleshooting protocol can help:

- Define Phenotypic Constraints: Based on experimental data or literature, define plausible ranges for key phenotypic fluxes (e.g., glucose uptake, growth rate, acetate production).

- Generate Constraint Sets: Systematically generate multiple (e.g., 1000) sets of constraints for these key fluxes within their defined ranges. This can be done by randomly sampling values and using FBA to find feasible min/max bounds for other related fluxes [31].

- Perform Constrained Sampling: Execute the flux sampling algorithm (e.g., OptGP) for each set of generated constraints. This ensures the sampling process is guided to explore the full, biologically relevant solution space [31].

- Validate with Visualization: Use dimensionality reduction techniques like Multi-Dimensional Scaling (MDS) to visualize the sampled solution sets. Compare the distribution of samples generated with and without the phenotypic constraints to confirm improved coverage [31].

FAQ 3: The geometricFBA algorithm fails to converge. What steps can I take?

The geometricFBA function in the COBRA Toolbox iteratively finds a central flux. If it fails to converge, you can adjust its parameters [30]:

- Increase

epsilon: This parameter is the convergence tolerance. Increasing it from the default (e.g.,1e-6) to a larger value (e.g.,1e-9) can help achieve convergence [30]. - Use

flexRel: Introduce a small flexibility factor (e.g.,1e-3) to the flux bounds. This provides the algorithm with minor flexibility to adjust constraints that might be causing numerical instability [30].

FAQ 4: How can I identify which fluxes are most critical for predicting a specific metabolic phenotype from a sampled solution space? After generating a comprehensive set of flux samples, you can identify important fluxes through a query-based analysis [31]:

- Exhaustive Flux Query: For each reaction flux in your model, select a specific flux value (from your samples) and define a query range (e.g., ±10% of the selected value).

- Sample Extraction: For each query, extract all flux samples from your master set where the corresponding flux value falls within the specified range.

- Rank by Specificity: Rank all fluxes by the average number of samples returned across all such queries. Fluxes that consistently return a low number of samples for a given value are considered more "important" or "predictive" because their value strongly constrains the possible states of the entire network [31].

- Validation: The validity of these identified important fluxes can be checked by comparing the flux distributions extracted using their values against experimental data, such as 13C-MFA flux measurements [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Infeasible FBA Models and Gap-Filling

Problem: Your metabolic model is infeasible, meaning no flux distribution satisfies all stoichiometric, thermodynamic, and capacity constraints, often due to gaps in the network.

Solution - Multiple Gap-Filling with MetaFlux: This methodology uses Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) to systematically identify and suggest minimal additions to the model to restore feasibility [32].

- Step 1: Define Fixed-Sets and Try-Sets. Categorize your model components:

- Fixed-Sets: Components you are confident in (e.g., core metabolic reactions from a well-curated PGDB).

- Try-Sets: Candidate components from a reference database (e.g., MetaCyc) that can be added to fix the model. This includes try-reactions, try-biomass metabolites, try-nutrients, and try-secretions [32].

- Step 2: Start from a Trivial Feasible Model. Begin the gap-filling process with a simple, trivially feasible model. This often means starting with an empty set of biomass metabolites. This ensures a feasible starting point [32].

- Step 3: Run Multiple Gap-Filling. Execute the MetaFlux algorithm. The software will solve a MILP problem to find the minimal combination of elements from your try-sets that, when added to the fixed-sets, allows the production of the maximal possible subset of your desired biomass metabolites [32].

- Step 4: Inspect and Integrate Suggestions. Review the suggested additions (reactions, nutrients, etc.). Use pathway visualization tools to inspect these suggestions in the context of your metabolic network before integrating them into your model [32].

Guide 2: Implementing Flux Sampling with OptGP

Problem: You need to characterize the full range of metabolic behaviors in an underdetermined model, but single-point FBA solutions are insufficient.

Solution - Optimized General Parallel (OptGP) Sampling: This is a protocol for performing flux sampling using the OptGP algorithm, which is well-suited for genome-scale models and supports parallelization [31].

- Step 1: Prepare the Model. Load your genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., using COBRApy) and set default constraints (e.g., glucose uptake, oxygen exchange).

- Step 2: Generate Phenotypic Constraints (Optional but Recommended). To ensure coverage of key phenotypes, generate multiple constraint sets:

- Step 3: Configure and Run OptGP. Set the sampling parameters. For each constraint set (or for the unconstrained model), run OptGP.

- Step 4: Post-Process and Analyze. Combine samples from all runs. Analyze the data by calculating summary statistics (mean, variance), flux correlations, and by performing the important flux analysis described in FAQ 4.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key computational tools and datasets essential for implementing Geometric FBA and Flux Sampling.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specifications/Source |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | A MATLAB-based software suite for constraint-based modeling. Contains implementations of geometricFBA, FVA, and sampling algorithms. |

OpenCOBRA GitHub [30] |

| COBRApy | A Python version of the COBRA Toolbox, enabling integration with modern Python-based machine learning and data science libraries. | COBRApy GitHub [31] |

| SSKernel Software | A dedicated package for computing the Solution Space Kernel (SSK), providing a low-dimensional geometric description of the FBA solution space. | Available as supplementary software with the SSKernel publication [29] |

| MetaCyc Database | A comprehensive database of metabolic pathways and enzymes. Used as a reference "try-set" for gap-filling algorithms like MetaFlux. | MetaCyc Website [32] |

| iML1515 / iJO1366 | Highly curated genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) of E. coli. Serve as standard testbeds for method development and validation. | Biocyc (iML1515); Bigg Database (iJO1366) [33] [31] |

| BRENDA Database | A primary resource for enzyme kinetic data (e.g., Kcat values), used for applying enzyme constraints to FBA models. | BRENDA Website [33] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Computing a Central Flux with geometricFBA

Objective: To find a unique, central flux vector for a metabolic model using the geometricFBA function in the COBRA Toolbox.

Methodology:

- Model Loading: Load a validated COBRA model structure into the MATLAB workspace.

- Parameter Configuration (Optional): If the algorithm fails to converge with default settings, adjust parameters:

- Execution: Run the

geometricFBAfunction. - Output Analysis: The output

centralFluxis a vector of reaction fluxes. This vector can be painted onto metabolic pathway diagrams for visualization and interpretation within the network context [32].

Protocol 2: Flux Sampling with Phenotypic Constraints

Objective: To generate a representative set of flux samples that cover the biologically relevant phenotypic space.

Methodology: This protocol is adapted from the work on acetate production in E. coli [31].

- Model and Bounds Setup: Initialize the model (e.g., iJO1366) and set the default medium conditions (e.g., aerobic growth on glucose).

- Constraint Set Generation: Programmatically generate 1000 sets of constraints for key phenotypic fluxes:

- For each set, randomly select a glucose uptake rate within a predefined experimental range.

- For that uptake rate, use FBA to find the minimum and maximum possible growth rates.

- Randomly select a growth rate within the calculated range.

- With both glucose uptake and growth rate fixed, use FBA to find the min/max range for a target product flux (e.g., acetate excretion).

- Randomly select a product flux value within its range.

- Store this triplet (glucoseuptake, growthrate, product_flux) as one constraint set.

- Parallelized Sampling: For each of the 1000 constraint sets, run the OptGP sampling algorithm with the following parameters per set:

thinning=10000,n_samples=20,n_processes=10[31]. This yields a total of 20,000 samples spread across the phenotypic space. - Data Aggregation: Combine the 20 samples from each of the 1000 runs into a single, comprehensive sample matrix for all subsequent analyses.

Visualizations

Geometric Representation of FBA Solution Space

Workflow for Flux Sampling and Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) model become infeasible when I integrate measured exchange rates?

Infeasibility occurs when the measured exchange rates you input conflict with the model's steady-state mass balance, reaction reversibility constraints, or other thermodynamic and capacity constraints [5]. The system of linear equations and inequalities (including Nr = 0 and lb ≤ r ≤ ub) has no solution, meaning no flux distribution exists that satisfies all constraints simultaneously [5]. Common causes include:

- Measurement inconsistencies: The provided set of measured fluxes violates the network stoichiometry [5].

- Incorrect reversibility assumptions: A measured flux value might force a reaction to operate in a thermodynamically infeasible direction [34].

Q2: What methods can I use to resolve an infeasible FBA problem? Two primary mathematical programming approaches can find minimal corrections to your measured flux values to restore feasibility [5]:

- Linear Programming (LP) Approach: Minimizes the sum of absolute deviations (

L1-norm) required in the measured fluxes. This method is robust and often used [5]. - Quadratic Programming (QP) Approach: Minimizes the sum of squared deviations (

L2-norm). This method is equivalent to a weighted least-squares approach, which is standard in classical Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) [5].

Q3: How can I validate the internal flux predictions from my FBA model? Since internal fluxes are notoriously difficult to measure directly, several validation strategies are employed [35] [36]:

- Comparison with 13C-MFA Data: This is considered one of the most robust validations. You can compare your FBA-predicted internal fluxes for central carbon metabolism against those estimated via high-resolution 13C-MFA on the same organism and condition [35] [34].

- Growth/No-Growth Predictions: Test if your model correctly predicts the viability of knockout strains or growth on specific carbon sources [36].

- Quantitative Growth Rate Comparison: Compare the model-predicted growth rate against the experimentally measured value across different conditions [36].

Q4: What is the advantage of using Parallel Labeling Experiments (PLEs) over a Single Labeling Experiment (SLE) in 13C-MFA? Using PLEs, where multiple 13C-tracers are used in parallel cultures, provides complementary information that significantly improves the precision and accuracy of the estimated fluxes [37]. Different tracers illuminate different pathways, and fitting the data from all experiments to a single metabolic model creates a synergistic effect, reducing the confidence intervals of the fluxes [37].

Q5: What does a "redundant" system mean in classical MFA, and why is it important?

In classical MFA, a system is redundant if there are linear dependencies between the mass balance equations (rows of the stoichiometric matrix) [5]. The degree of redundancy (degR) is calculated as m - rank(NU), where m is the number of metabolites [5]. Redundancy is crucial because it allows for statistical consistency checks. A redundant system enables you to test the goodness-of-fit between your model and the measured data, typically using a χ2-test, to validate your model [35] [5].

Q6: How can I handle a 13C-MFA model that is underdetermined, even with my labeling data? An underdetermined system has infinite solutions. To tackle this, you can [10]:

- Add more constraints: Integrate additional experimental data, such as enzyme capacity constraints or quantitative metabolite concentration data for INST-MFA [10].