Untargeted Metabolomics: A Comprehensive Guide to Global Metabolic Profiling in Disease Research and Drug Discovery

Untargeted metabolomics provides an unbiased, comprehensive analysis of the complete set of small-molecule metabolites in a biological system, offering a direct snapshot of biochemical activity and physiological status.

Untargeted Metabolomics: A Comprehensive Guide to Global Metabolic Profiling in Disease Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

Untargeted metabolomics provides an unbiased, comprehensive analysis of the complete set of small-molecule metabolites in a biological system, offering a direct snapshot of biochemical activity and physiological status. This article explores the foundational principles, advanced methodologies, and practical applications of untargeted metabolomics for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the complete workflow from experimental design and data acquisition to bioinformatics analysis and biological interpretation, highlighting its transformative role in biomarker discovery, understanding disease mechanisms, and advancing precision medicine. The content also addresses key challenges in metabolite identification and data validation while comparing untargeted approaches with targeted strategies to guide appropriate experimental design.

The Foundations of Untargeted Metabolomics: An Unbiased Lens on Biological Systems

Untargeted metabolomics is a systematic, unbiased approach for comprehensively profiling the complete set of small-molecule metabolites within a biological system. Unlike targeted methods that focus on predefined compounds, untargeted metabolomics aims to detect and measure both known and novel metabolites without prior assumptions, providing a holistic view of the metabolic state [1]. This methodology has emerged as a pivotal tool in modern biosciences, enabling researchers to capture the holistic metabolic state of samples derived from cell cultures, clinical specimens, food matrices, or environmental sources [2]. By combining high-resolution mass spectrometry with complementary analytical techniques, untargeted metabolomics provides an unprecedented window into dynamic biochemical pathways, allowing scientists to discover novel biomarkers, elucidate complex disease mechanisms, and accelerate drug and nutritional research [2].

The fundamental value of untargeted metabolomics lies in its ability to reveal the functional outcome of physiological processes and environmental influences. As the most downstream product of the omics cascade, metabolites offer the most immediate reflection of cellular activity and phenotype. The metabolome represents the final response of a biological system to genetic, environmental, or therapeutic interventions, making its comprehensive profiling particularly valuable for understanding complex biological mechanisms [3]. This approach is especially effective for exploratory studies such as early-stage biomarker discovery, drug mechanism research, and evaluating the metabolic effects of diet or environmental exposures [1].

Core Principles and Technological Foundations

Analytical Platforms and Technologies

Untargeted metabolomics relies primarily on advanced separation and detection technologies to achieve broad coverage of diverse metabolite classes. The field is dominated by several complementary analytical platforms, each with distinct strengths and applications:

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS): Serves as the workhorse for broad-spectrum profiling due to its versatility in detecting metabolites across diverse molecular weights and polarities. LC-MS offers superior sensitivity for detecting both abundant compounds and rare, low-abundance metabolites with precision [3]. Modern high-resolution mass spectrometers now routinely achieve parts-per-billion sensitivity, enabling detection of low-abundance metabolites that were once beyond reach [2].

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS): Preferred for volatile metabolites in environmental or nutritional studies, offering excellent separation efficiency and reproducibility [2]. This technology is particularly valuable for analyzing volatile organic compounds and metabolites that can be readily derivatized for gas chromatographic separation.

Capillary Electrophoresis-Mass Spectrometry (CE-MS): Excels at polar compound detection, providing complementary coverage to LC-MS-based methods [2]. This technique is especially useful for analyzing highly polar ionic metabolites that may not be well-retained in reversed-phase liquid chromatography.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Facilitates non-destructive analysis of complex mixtures and provides structural information without extensive sample preparation [2]. While generally less sensitive than mass spectrometry-based approaches, NMR offers excellent quantitative capabilities and can identify novel compounds without reference standards.

Table 1: Key Analytical Technologies in Untargeted Metabolomics

| Technology | Key Applications | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| LC-MS | Broad-spectrum metabolic profiling | Excellent coverage and sensitivity; handles diverse compound classes | Matrix effects; requires method optimization |

| GC-MS | Volatile compounds, metabolic profiling | High separation efficiency; robust compound identification | Requires derivatization for many metabolites |

| CE-MS | Polar ionic metabolites | Excellent for polar compounds; minimal sample requirements | Limited compatibility with non-polar metabolites |

| NMR | Structural elucidation, absolute quantification | Non-destructive; provides structural information; quantitative | Lower sensitivity compared to MS techniques |

Metabolite Coverage and Chemical Diversity

Untargeted metabolomics platforms detect an extensive range of biochemical compounds spanning multiple chemical classes and pathways. Leading commercial platforms can identify thousands of metabolites, with coverage continuously expanding through technological advancements and database improvements. Metabolon's reference library, for instance, contains over 5,400 annotated metabolites across 70 major biochemical pathways, providing comprehensive representation of diverse biological phenotypes [3]. Other providers like MetwareBio offer databases encompassing over 280,000 curated compounds, combining in-house, public, and AI-augmented entries to ensure high-confidence metabolite identification [1].

The detectable metabolite classes include amino acids and their derivatives, carbohydrates, organic acids, nucleotides, lipids, amines, alcohols, ketones, aldehydes, steroids, bile acids, vitamins, and various secondary metabolites [1]. These compounds span critical pathways such as energy metabolism, amino acid metabolism, nucleotide biosynthesis, lipid metabolism, and redox balance, enabling comprehensive insights into cellular function and systemic metabolic regulation [1].

Table 2: Major Metabolite Classes Detectable in Untargeted Metabolomics

| Metabolite Class | Representative Compounds | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Amino acids and derivatives | Glycine, L-threonine, L-arginine | Protein synthesis; energy metabolism; signaling |

| Lipids | O-acetylcarnitine, γ-linolenic acid, lysophosphatidylcholine | Membrane structure; energy storage; signaling |

| Organic acids and derivatives | 3-hydroxybutyric acid, adipic acid, hippuric acid | Energy metabolism; detoxification; microbial co-metabolism |

| Nucleotides and derivatives | Adenine, guanine, 2'-Deoxycytidine | Genetic information; energy transfer; signaling |

| Carbohydrates and derivatives | D-glucose, glucosamine, D-fructose 6-phosphate | Energy source; structural components; glycosylation |

| Benzenoids and derivatives | Benzoic acid, 3,4-dimethoxyphenylacetic acid | Plant secondary metabolites; microbial metabolites |

| Coenzymes and vitamins | Folic acid, pantothenic acid, vitamin D3 | Enzyme cofactors; antioxidants; regulatory molecules |

| Bile acids | Glycocholic acid, deoxycholic acid, taurolithocholic acid | Lipid digestion; signaling molecules; microbiota interactions |

Experimental Workflow and Methodologies

The untargeted metabolomics workflow comprises multiple interconnected stages, each requiring careful optimization to ensure data quality and biological relevance. The entire process involves complex processing, analysis, and interpretation tasks where visualization plays a crucial role at every stage for data inspection, evaluation, and sharing capabilities [4].

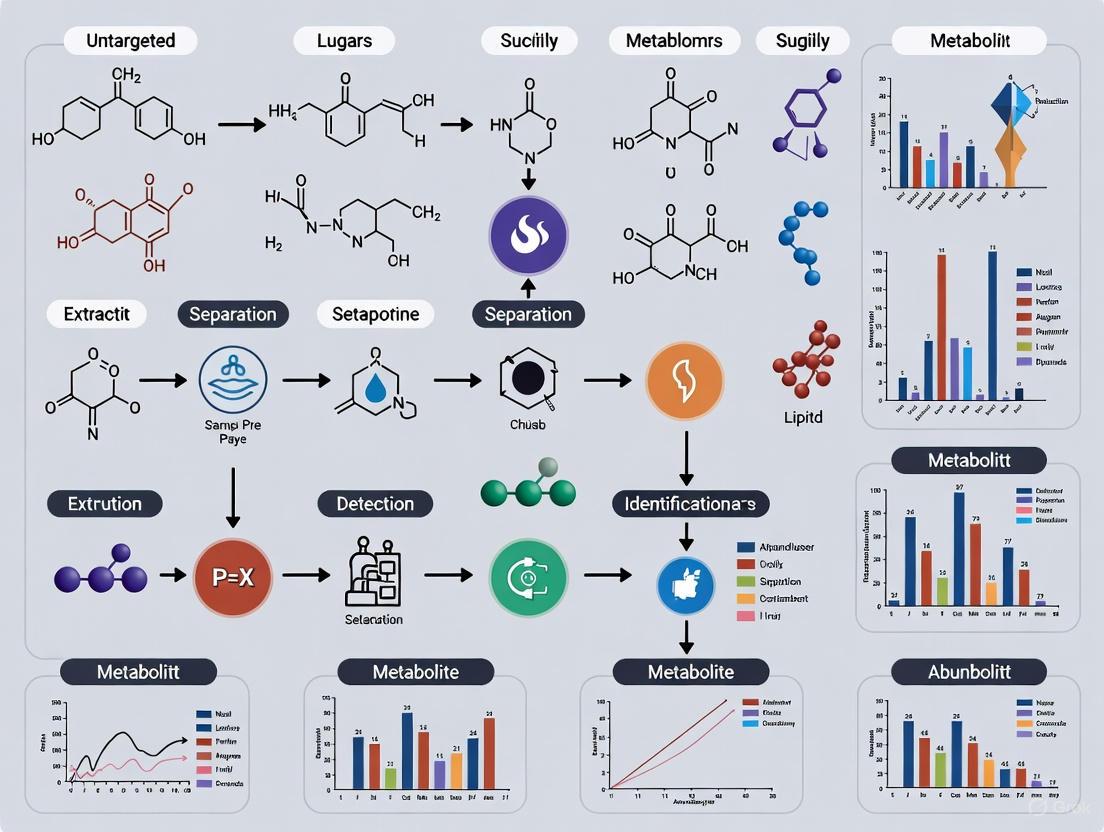

Figure 1: Untargeted Metabolomics Workflow

Sample Preparation and Metabolite Extraction

The initial phase of sample preparation is critical for maintaining metabolic integrity and ensuring analytical reproducibility. Sample-specific extraction protocols tailored to the physicochemical characteristics of each sample type maximize metabolite recovery and signal consistency for diverse matrices including tissues, biofluids, environmental samples, and cell cultures [1]. Key considerations include:

Sample Collection and Quenching: Rapid quenching of metabolic activity is essential to preserve the in vivo metabolic state. This typically involves flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen or using specialized quenching solutions for cell cultures.

Metabolite Extraction: Multi-solvent systems (e.g., methanol, acetonitrile, chloroform, water) are employed to extract metabolites with diverse physicochemical properties. The choice of extraction method significantly impacts metabolite coverage and should be optimized for specific sample types.

Quality Control Implementation: A standardized, multi-point quality control system includes over 10 indicators—such as blanks, solvents, pooled QCs, internal standards, and reference samples—to ensure data accuracy, reproducibility, and batch comparability throughout the workflow [1].

Recommended sample requirements vary by sample type. For liquid samples like plasma or serum, 100μL is recommended, with a minimum of 20μL, while biological replication should exceed 30 for human studies and 6 for animal studies [1]. Proper sample randomization and inclusion of quality control samples throughout the analytical sequence are essential for identifying and correcting technical variations.

Analytical Detection and Separation

Chromatographic separation coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry forms the core of untargeted metabolomics detection. Utilizing multiple chromatographic separation mechanisms significantly enhances metabolite coverage:

Reversed-Phase Chromatography (T3 columns): Effective for separating medium to non-polar metabolites including lipids, bile acids, and steroids.

Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography (HILIC): Ideal for polar metabolites such as amino acids, carbohydrates, nucleotides, and organic acids.

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) Parameters: Advanced LC-MS platforms utilize ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) with sub-2μm particle columns to achieve superior separation efficiency, coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometers capable of accurate mass measurements with errors <5 ppm.

Mass spectrometry detection typically employs both positive and negative ionization modes to maximize metabolite coverage. Data-independent acquisition (DIA) methods like SWATH-MS, as well as data-dependent acquisition (DDA), are commonly used to fragment multiple ions simultaneously, generating comprehensive MS/MS spectral data for confident metabolite identification [4].

Data Processing and Metabolite Identification

Following data acquisition, raw spectral data undergoes extensive processing to extract meaningful biological information. This complex process involves multiple computational steps where visualization provides core components of data inspection, evaluation, and sharing capabilities [4].

Figure 2: Data Processing Pipeline

The data processing workflow includes several key steps:

Peak Detection and Deconvolution: Algorithmic identification of mass spectral features from raw data, distinguishing true metabolite signals from chemical noise and accounting for in-source fragments, adducts, and isotopes [3].

Retention Time Alignment: Correction of retention time shifts across multiple samples to ensure consistent feature matching, addressing the challenging cross-sample alignment of features affected by retention time and mass shifts [4].

Metabolite Annotation and Identification: Confidence levels in metabolite identification follow the Metabolomics Standards Initiative guidelines, ranging from Level 1 (highest confidence, confirmed with reference standard) to Level 5 (lowest confidence) [3]. Leading platforms employ a chemocentric approach, prioritizing true metabolite identification over significant ion feature changes, enhancing statistical robustness [3].

Quality Assessment: Rigorous quality evaluation covers total ion current inspection, PCA, correlation analysis, and CV distribution, among other metrics [1]. This includes assessing potential matrix effects and experimental data quality affirmation throughout the processing steps [4].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful untargeted metabolomics requires carefully selected reagents and materials to ensure analytical robustness. The following table details key research reagent solutions essential for experimental workflows:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Untargeted Metabolomics

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Extraction Solvents (methanol, acetonitrile, chloroform) | Protein precipitation and metabolite extraction | Multi-solvent systems maximize coverage of diverse metabolite classes; pre-cooled solvents enhance metabolite stability |

| Internal Standards (isotopically labeled compounds) | Quality control and quantification correction | Correct for technical variability; should cover multiple chemical classes; added prior to extraction |

| Quality Control Materials (pooled QC samples, solvent blanks, reference standards) | Monitoring analytical performance | Pooled QCs from all samples assess system stability; blanks identify contamination; reference standards validate identifications |

| Chromatography Columns (T3 reversed-phase, HILIC) | Metabolite separation | Column chemistry selection dramatically impacts metabolite coverage; dedicated columns for different metabolite classes recommended |

| Mobile Phase Additives (formic acid, ammonium acetate, ammonium hydroxide) | Modifying separation and ionization | Acidic additives enhance positive ionization; basic additives enhance negative ionization; volatile buffers compatible with MS |

| Mass Spectrometry Calibrants | Instrument calibration | Ensure mass accuracy; infused continuously or periodically during analysis depending on instrument platform |

Data Analysis and Bioinformatics

Statistical Analysis and Visualization Approaches

Untargeted metabolomics generates complex, high-dimensional datasets requiring sophisticated statistical approaches and visualization strategies for meaningful interpretation. Data visualization is a crucial step at every stage of the metabolomics workflow, where it provides core components of data inspection, evaluation, and sharing capabilities [4].

The statistical framework typically includes:

Multivariate Analysis: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) are routinely employed to identify patterns, trends, and group separations within the metabolic data. These approaches help reduce data dimensionality while preserving metabolic variance structure.

Univariate Statistics: T-tests, ANOVA, and fold-change calculations identify significantly altered metabolites between experimental conditions. Volcano plots visually represent both statistical significance and magnitude of change, giving a snapshot view of treatment impacts and affected metabolites [4] [1].

Cluster Analysis and Heatmaps: Hierarchical clustering and heatmap visualizations organize metabolites and samples based on similarity, revealing coherent metabolic patterns and subgroups within the data [4].

Advanced visual analytics approaches have become increasingly important for untargeted metabolomics. Information visualization (InfoVis) research focuses on how to best understand, explore, and analyze data to generate knowledge through interactive and exploratory visualizations [4]. These visual analysis models represent sensemaking as a non-linear, often circular process involving data, models, visualizations, and knowledge, all connected by user-driven interaction [4].

Pathway and Functional Interpretation

Biological interpretation represents the ultimate goal of untargeted metabolomics, transforming spectral data into physiological insights. Pathway analysis tools map identified metabolites onto known biochemical pathways, revealing functionally coordinated metabolic changes:

Pathway Enrichment Analysis: Statistical approaches (e.g., Fisher's exact test, hypergeometric test) identify biochemical pathways significantly enriched with altered metabolites, prioritizing biologically relevant systems.

Metabolic Network Visualization: Network-based representations illustrate relationships between metabolites and pathways, highlighting key regulatory nodes and biochemical connections [4].

Integration with Multi-Omics Data: Combining metabolomic data with transcriptomic, proteomic, and genomic datasets provides systems-level insights into regulatory mechanisms and biological processes [1] [3].

Leading bioinformatics platforms, such as Metabolon's Integrated Bioinformatics Platform, combine multivariate analysis tools with data enrichment features like pathway mapping and specialized analytical lenses, enabling researchers to seamlessly transition between different analytical views and biological interpretations [3].

Applications in Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Untargeted metabolomics has become an indispensable tool across diverse research domains, with particularly significant impact in drug research and development. It greatly facilitates the entire drug development pipeline from understanding disease mechanisms and identifying drug targets to predicting drug response and enabling personalized treatment [5].

Key applications include:

Disease Mechanism Elucidation and Biomarker Discovery: By profiling global metabolic changes in patient samples, researchers can uncover metabolic signatures associated with cancer, metabolic disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, and other pathological conditions. This approach supports early diagnosis, patient stratification, and therapeutic monitoring in clinical and translational research [1].

Pharmacology and Drug Response Studies: Untargeted metabolomics enables comprehensive evaluation of drug-induced metabolic changes, helping assess drug efficacy, toxicity, and off-target effects by capturing metabolic shifts in blood, tissue, or urine samples [1]. This approach is widely used in preclinical studies to support drug mechanism elucidation and safety evaluation [1].

Microbial Metabolism and Host-Microbiome Interaction: This approach provides a powerful tool for studying microbial metabolism and host-microbiome interactions, allowing researchers to track microbial-derived metabolites, analyze gut microbial activity, and explore how microbiota influence host physiology [1].

The market growth for untargeted metabolomics reflects its expanding applications, with the market size estimated at USD 494.50 million in 2024 and expected to reach USD 540.40 million in 2025, at a CAGR of 10.42% to reach USD 1,093.34 million by 2032 [2]. This growth is driven by increasing adoption across academic and government research, pharmaceutical and biotechnology development, as well as food and beverage quality control [2].

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

Untargeted metabolomics continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping its future development. Algorithmic innovations have kept pace with analytical advancements, with machine learning frameworks now embedded into data processing pipelines to automate peak detection, deconvolution, and compound annotation [2]. These software advancements have dramatically increased throughput and reproducibility, allowing research teams to focus on biological interpretation rather than manual curation [2].

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning has transformed raw spectral data into actionable insights, reducing the time from sample acquisition to meaningful interpretation [2]. Concurrently, cloud-native infrastructures and FAIR data principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) have fostered a collaborative ethos, enabling secure, cross-institutional sharing of high-dimensional datasets without compromising privacy or intellectual property [2].

As untargeted metabolomics converges with precision medicine initiatives and environmental monitoring, these transformative shifts underscore a broader trend toward integrated, systems-level exploration of metabolic networks [2]. The approach continues to redefine our understanding of biochemical systems, providing an essential toolkit for decoding the complex metabolic underpinnings of health, disease, and therapeutic intervention.

In conclusion, untargeted metabolomics represents a powerful paradigm for comprehensive biochemical phenotyping, enabling researchers to move beyond targeted hypothesis testing to exploratory discovery of novel metabolic pathways and biomarkers. As technological capabilities continue to advance and computational methods become increasingly sophisticated, untargeted metabolomics is poised to remain at the forefront of systems biology and personalized medicine initiatives, providing unprecedented insights into the metabolic basis of biological function and dysfunction.

Untargeted metabolomics represents a groundbreaking approach in molecular biology, offering an unparalleled exploration of the metabolome—the complete set of metabolites within a biological sample [6]. Unlike targeted metabolomics, which focuses on pre-selected metabolites, untargeted metabolomics embraces a holistic strategy, aiming to capture as many small molecules as possible without bias toward specific compounds or pathways [6] [7]. This comprehensive scope allows researchers to gain deeper insights into the complex biochemical activities within cells, reflecting the cumulative effects of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors on an organism [6].

The fundamental advantage of this approach lies in its ability to uncover novel metabolites and unexpected metabolic shifts that might otherwise remain undetected in targeted analyses [6]. By providing a snapshot of the biochemical phenotype, untargeted metabolomics offers a unique window into the metabolic dynamics underpinning diverse biological processes, from disease mechanisms to therapeutic interventions [6]. The exploitation of untargeted metabolomics implies no prior decision about the metabolites or pathways to be studied, thus allowing screening of metabolic phenomena and bringing an objective perspective to biological discovery [7].

Core Advantages in Metabolic Discovery

Comprehensive Metabolome Coverage

The primary advantage of untargeted metabolomics is its capacity for extensive metabolome coverage without predetermined constraints. While targeted approaches focus on specific compounds, potentially overlooking significant metabolic changes, untargeted analysis captures a broader spectrum of the metabolome [6]. This inclusivity is essential for discovering unknown metabolites that could play critical roles in health and disease [6]. In practice, a single untargeted experiment can simultaneously analyze hundreds to thousands of metabolites, as demonstrated in a recent CHO cell study that identified 563 cellular and 386 supernatant metabolites [7].

Discovery of Unexpected Metabolic Shifts

Untargeted metabolomics facilitates the identification of unexpected metabolic shifts due to disease, environmental exposure, or therapeutic interventions [6]. Such discoveries can lead to new hypotheses and research directions, driving innovation in fields like drug discovery and personalized medicine [6]. For instance, in bioprocessing applications, untargeted approaches have revealed metabolic reprogramming events that correlate with higher productivity, including the shift from lactate production to consumption and the identification of unexpected metabolites like citraconate and 5-aminovaleric acid [7].

Table: Key Advantages of Untargeted Metabolomics for Novel Discovery

| Advantage | Technical Basis | Impact on Research |

|---|---|---|

| Unbiased Metabolic Profiling | No pre-selection of metabolites or pathways [7] | Enables discovery of previously unknown metabolic alterations [6] |

| Comprehensive Coverage | Detection of hundreds to thousands of metabolites simultaneously [7] | Provides holistic view of metabolic networks and interactions [6] |

| Novel Metabolite Discovery | Ability to detect unannotated spectral features [6] | Identifies new biomarkers and metabolic pathway components [6] |

| Unexpected Shift Detection | Data-driven analysis without hypothesis constraints [7] | Reveals unanticipated metabolic adaptations to stimuli [6] |

Experimental Framework and Methodologies

Untargeted Metabolomics Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for untargeted metabolomics, from sample preparation to data interpretation:

Sample Preparation Protocols

Proper sample preparation is critical for maintaining metabolic integrity and ensuring comprehensive metabolite detection. The following protocol outlines key steps:

- Rapid Quenching: Immediate termination of metabolic activity using liquid nitrogen or cold methanol (-40°C) to preserve metabolic profiles [7].

- Metabolite Extraction: Utilization of dual-phase extraction systems (e.g., methanol/chloroform/water) to recover both hydrophilic and lipophilic metabolites [7].

- Protein Precipitation: Removal of proteins by cold organic solvents or filtration to prevent interference during analysis [7].

- Sample Normalization: Adjustment based on cell count or protein content to ensure comparability across samples [7].

LC-MS/MS Analytical Parameters

Liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) serves as the cornerstone analytical platform for untargeted metabolomics. The following parameters are critical for optimal performance:

Table: LC-MS/MS Parameters for Untargeted Metabolomics

| Parameter | Settings | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatography | Reversed-phase (C18) or HILIC columns | Separation of diverse metabolite classes |

| Gradient | 10-20 minute organic solvent gradient | Optimal separation of metabolites |

| Mass Analyzer | High-resolution (Orbitrap or Q-TOF) | Accurate mass measurement for elemental composition |

| Mass Range | m/z 50-1500 | Broad coverage of small molecules |

| Fragmentation | Data-dependent acquisition (DDA) | Structural elucidation via MS/MS spectra |

| Collision Energy | Stepped (e.g., 20, 40, 60 eV) | Comprehensive fragmentation patterns |

Data Processing and Visualization Strategies

From Raw Data to Biological Insights

The transformation of raw spectral data into biological knowledge requires sophisticated computational approaches and visualization strategies:

Key Visualization Techniques for Data Exploration

Effective data visualization is crucial at every stage of the untargeted metabolomics workflow, providing core components of data inspection, evaluation, and sharing capabilities [4]. The following visualization strategies have emerged as particularly valuable:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA) Scores Plots: Provide overview of sample groupings and outliers, highlighting overall metabolic differences between experimental conditions [4] [7].

- Volcano Plots: Combine statistical significance (p-values) with magnitude of change (fold-change) to highlight metabolites most affected by experimental conditions [4].

- Cluster Heatmaps: Visualize patterns in metabolite abundance across sample groups, revealing co-regulated metabolites and sample clusters [4].

- Pathway Maps: Display metabolites within their biochemical context, highlighting affected pathways and network relationships [4].

- Interactive Spectral Viewers: Allow exploration of raw MS/MS spectra for structural elucidation and annotation validation [4].

Advanced Integration with Mechanistic Modeling

Data-Driven Modeling Approaches

The integration of untargeted metabolomics with mechanistic modeling represents a cutting-edge approach for extracting maximal biological insight from complex metabolic data. Recent advances have demonstrated the power of combining these methodologies:

Application Case Study: CHO Cell Bioprocessing

A recent study exemplifies the power of combining untargeted metabolomics with mechanistic modeling [7]. Researchers analyzed LC/MS/MS metabolomics data (563 cellular and 386 supernatant metabolites) to determine key metabolites involved in productivity improvement in CHO cell cultures [7]. The approach yielded significant insights:

Table: Key Discoveries from CHO Cell Metabolomics Study

| Discovery Category | Specific Findings | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Network Expansion | Original network: 127 reactions → Expanded network: 370 reactions [7] | Significantly enhanced coverage of metabolic capabilities |

| Novel Metabolites | Identification of citraconate and 5-aminovaleric acid [7] | Revealed previously unknown metabolic players in productivity |

| Pathway Analysis | 300 metabolic pathways identified; 25 associated with production [7] | Provided mechanistic understanding of productivity drivers |

| Key Metabolites | 21 key metabolites significant for productivity improvement [7] | Offered targets for rational process optimization |

The mechanistic modeling approach using elementary flux modes (EFM)-based column generation successfully identified and simulated the underlying metabolic pathways, paving the way for rational process optimization supported by mechanistic understanding [7]. This methodology demonstrates how untargeted metabolomics can move beyond simple biomarker discovery to provide genuine mechanistic insights into complex biological systems.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful untargeted metabolomics studies require carefully selected reagents and materials to ensure comprehensive metabolite coverage and analytical robustness.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Untargeted Metabolomics

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cold Methanol (-40°C) | Metabolic quenching and extraction [7] | Preserves labile metabolites and enzymatic activity |

| Dual-Phase Extraction Solvents | Simultaneous recovery of hydrophilic and lipophilic metabolites [7] | Chloroform:methanol:water systems provide broad coverage |

| UPLC/MS-Grade Solvents | Mobile phase for high-resolution separation | Minimizes background interference and ion suppression |

| HILIC & Reversed-Phase Columns | Chromatographic separation of diverse metabolites | Complementary selectivity for comprehensive coverage |

| Mass Spectrometry Calibrants | Instrument calibration for mass accuracy | Essential for confident metabolite identification |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Standards | Quality control and semi-quantitation | Corrects for matrix effects and analytical variability |

| Chemical Derivatization Reagents | Enhancement of detection for certain metabolite classes | Improves sensitivity for amines, organic acids, etc. |

| Database Subscription Services | Metabolite annotation and identification | Critical for structural elucidation (e.g., HMDB, MassBank) |

Untargeted metabolomics provides an unparalleled platform for discovering novel metabolites and unexpected metabolic shifts that underlie biological processes and disease states [6]. By embracing a comprehensive, unbiased approach to metabolic profiling, researchers can uncover previously overlooked metabolic alterations and identify new biomarkers and therapeutic targets [6]. The integration of advanced computational approaches, particularly mechanistic modeling and sophisticated visualization strategies, enhances our ability to extract meaningful biological insights from complex metabolomics datasets [4] [7]. As the field continues to evolve with improvements in analytical technologies, computational methods, and database resources, untargeted metabolomics is poised to remain at the forefront of biological discovery, systems biology, and precision medicine initiatives [6].

The Metabolome as a Direct Signature of Phenotype and Biochemical Activity

Metabolites, defined as the biochemical end products of cellular regulatory processes, constitute the metabolome of a biological system and provide a functional readout of its phenotypic state [8] [9]. Unlike other omics layers, the metabolome represents the ultimate response to genetic, environmental, and pathophysiological influences, capturing the dynamic biochemical activity within cells, tissues, or whole organisms at a specific point in time [8] [10]. The quantitative measurement of this dynamic, multiparametric metabolic response—a discipline known as metabonomics—offers a direct signature of phenotype by revealing the functional outcome of complex biological networks [10]. In the context of untargeted metabolomics for global metabolic profile discovery, researchers can simultaneously profile thousands of small molecules without predefined targets, thereby uncovering novel biomarkers and mechanistic insights into disease processes, drug responses, and physiological adaptations [11] [9] [12].

Analytical Foundations of Untargeted Metabolomics

Core Technologies and Instrumentation

Untargeted metabolomics relies on advanced analytical platforms to achieve comprehensive coverage of the metabolome, which exhibits vast chemical diversity and concentration ranges. The two primary technologies employed are Mass Spectrometry (MS) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, each with distinct advantages and applications [10] [2].

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) has emerged as the predominant platform due to its high sensitivity, broad dynamic range, and capability to detect thousands of metabolite features in a single analysis [11] [12]. A typical LC-MS workflow for untargeted metabolomics involves:

- Metabolite Separation: Ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) with reverse-phase C18 columns provides high-resolution separation of metabolites prior to mass analysis [12].

- Mass Analysis: High-resolution mass spectrometers, particularly quadrupole time-of-flight (Q-TOF) and Orbitrap instruments, enable accurate mass measurement with precision sufficient for putative compound identification [12] [2].

- Ionization Techniques: Electrospray ionization (ESI) is most commonly employed, with both positive and negative ion modes necessary to capture the broadest possible metabolome coverage [12].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy offers complementary advantages, including non-destructive analysis, minimal sample preparation, and absolute quantification capabilities without requiring internal standards [10]. NMR is particularly valuable for large-scale epidemiologic studies due to its high reproducibility and ability to detect a wide variety of metabolites from dietary, gut microbial, and host metabolism sources in a single analytical sweep [10].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Analytical Platforms for Untargeted Metabolomics

| Platform | Sensitivity | Coverage | Quantification | Throughput | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC-MS | High (pM-fM) | Broad (>10,000 features) | Relative (requires standards) | Medium-High | Biomarker discovery, pathway analysis, drug metabolism |

| GC-MS | High (pM-fM) | Volatile/semi-volatile compounds | Relative (requires derivation) | Medium | Metabolic disorders, toxicology, plant metabolomics |

| NMR | Low (μM-mM) | Limited (~100-200 compounds) | Absolute | High | Epidemiologic studies, in vivo metabolism, structural ID |

| CE-MS | High (pM-fM) | Polar/ionic compounds | Relative | Medium | Polar metabolome, energy metabolism, clinical diagnostics |

Experimental Workflow and Sample Preparation

Robust sample preparation is critical for meaningful untargeted metabolomics results. Variations in collection, handling, and storage can introduce artefacts that overshadow biological variation [10]. The following protocol for plasma metabolomics exemplifies the stringent requirements for sample integrity:

Plasma Sample Preparation Protocol [12]:

- Collection: Collect blood in EDTA tubes after 10-12 hours of fasting, followed by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C to separate plasma.

- Storage: Aliquot plasma (100-200 μL) into sterile tubes and store immediately at -80°C to minimize degradation.

- Metabolite Extraction: Thaw samples on ice and mix 100 μL plasma with 700 μL of cold extraction solvent (methanol:acetonitrile:water, 4:2:1, v/v/v) containing internal standards.

- Precipitation: Vortex for 1 minute, incubate at -20°C for 2 hours, then centrifuge at 25,000 × g at 4°C for 15 minutes.

- Preparation for Analysis: Transfer 600 μL of supernatant to a new tube, dry using a vacuum concentrator, and reconstitute in 180 μL of methanol:water (1:1, v/v).

- Clearance: Vortex for 10 minutes, then centrifuge at 25,000 × g at 4°C for 15 minutes to remove insoluble debris before LC-MS analysis.

For urine-based studies, 24-hour collections are preferred as they provide time-averaged metabolic patterns, though spot or overnight collections are acceptable when 24-hour collection is infeasible [10]. Strict standardization of operating procedures and comprehensive metadata recording are essential throughout the process [10].

Diagram 1: Untargeted metabolomics workflow from sample to biological insight.

Data Processing and Bioinformatics Pipeline

From Raw Data to Metabolic Features

The transformation of raw instrumental data into biologically interpretable information requires sophisticated bioinformatic pipelines. LC-MS-based untargeted metabolomics generates thousands of peaks, each with a unique m/z value and retention time, creating substantial computational challenges [11]. The primary steps include:

- Peak Detection and Alignment: Nonlinear retention-time alignment algorithms correct for experimental drift without requiring internal standards. The XCMS software package implements such algorithms to identify dysregulated metabolite features between sample groups [11].

- Feature Matrix Creation: Peak intensities are aligned across all samples to create a data matrix where rows represent samples and columns represent metabolite features [11].

- Meta-Analysis for Complex Study Designs: Tools like metaXCMS enable second-order analysis across multiple sample groups (e.g., "healthy" vs. "active disease" vs. "inactive disease") to prioritize interesting metabolite features prior to structural identification [11].

Statistical Analysis and Biomarker Discovery

Multivariate statistical modeling is essential for effective data visualization and biomarker discovery while controlling for false positive associations [10]. Both unsupervised and supervised methods are employed:

- Unsupervised Methods: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) provides initial data overview and identifies inherent clustering patterns and outliers.

- Supervised Methods: Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) and Orthogonal PLS-DA (OPLS-DA) maximize separation between predefined sample classes and identify features most responsible for differentiation.

Metabolome-wide association studies (MWA) share similarities with genome-wide association studies, enabling discovery of novel associations while generating complex data arrays requiring specialized statistical approaches to manage false discovery rates [10].

Advanced Applications in Phenotype Decoding

Distinguishing Disease Subtypes through Metabolic Signatures

Untargeted metabolomics has demonstrated remarkable utility in distinguishing pathologically similar conditions with different etiologies. A recent study of hypercholesterolemia subtypes exemplifies this application:

Experimental Design [12]:

- Cohorts: Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) with LDL-C ≥190 mg/dL and confirmed pathogenic variants; non-genetic hypercholesterolemia (HC) with LDL-C 130-159 mg/dL without FH variants; healthy controls with LDL-C <100 mg/dL.

- Analytical Platform: UPLC-Q-TOF/MS with both positive and negative ion modes.

- Statistical Analysis: Univariate and multivariate analyses followed by pathway enrichment using KEGG database.

Key Findings [12]:

- FH Signature: Distinct alterations in bile acid biosynthesis and steroid metabolism, with significant downregulation of cholic acid and elevation of 17α-hydroxyprogesterone.

- HC Signature: Characterized by increased uric acid and choline levels, with dysregulation in oleic acid and linoleic acid metabolism.

- Shared Metabolic Disturbances: Both groups showed alterations in sphinganine, D-α-hydroxyglutaric acid, and pyridoxamine, suggesting common pathways of cholesterol pathology.

Table 2: Key Metabolic Biomarkers Differentiating Hypercholesterolemia Subtypes

| Metabolite | Chemical Class | FH vs. Control | HC vs. Control | Proposed Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17α-Hydroxyprogesterone | Steroid hormone | Significantly upregulated | Unchanged | Potential FH-specific biomarker |

| Cholic Acid | Bile acid | Significantly downregulated | Unchanged | Impaired bile acid synthesis in FH |

| Uric Acid | Purine metabolite | Unchanged | Significantly upregulated | Gout risk indicator in HC |

| Choline | Quaternary ammonium | Unchanged | Significantly upregulated | Altered phospholipid metabolism in HC |

| Sphinganine | Sphingolipid | Dysregulated | Dysregulated | Common sphingolipid pathway disruption |

| Linoleic Acid | Fatty acid | Unchanged | Dysregulated | Oxidative stress and inflammation link |

Metabolomics Activity Screening (MAS) for Phenotype Modulation

Metabolomics activity screening integrates metabolomics data with pathway and systems biology information to identify endogenous metabolites that can actively modulate phenotypes [9]. This approach has revealed metabolites that influence diverse biological processes:

- Stem Cell Differentiation: Metabolic oxidation regulates embryonic stem cell differentiation through α-ketoglutarate and other TCA cycle intermediates [9].

- Oligodendrocyte Maturation: A metabolomics-guided approach discovered a metabolite that enhances oligodendrocyte maturation, with potential applications for remyelination therapies [9].

- Immune Function: Metabolites including L-arginine modulate T cell metabolism and enhance anti-tumor activity [9].

- Chronic Pain: Altered sphingolipids, including sphingosine-1-phosphate, have been implicated in chronic pain of neuropathic origin [9].

Diagram 2: Metabolomics Activity Screening (MAS) workflow for phenotype modulation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful untargeted metabolomics requires carefully selected reagents and materials to ensure reproducibility and accuracy. The following table details essential components for a typical untargeted metabolomics workflow:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Untargeted Metabolomics

| Category | Specific Items | Function & Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | EDTA tubes, citrate tubes, sterile Eppendorf tubes | Biofluid collection and preservation; prevents coagulation and metabolic degradation | Maintain samples at 4°C during processing; avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles [10] |

| Extraction Solvents | Methanol, acetonitrile, water (HPLC grade), chloroform | Metabolite extraction and protein precipitation | Use cold solvents (4°C or -20°C); methanol:acetonitrile:water (4:2:1) shown effective for plasma [12] |

| Internal Standards | Stable isotope-labeled compounds | Quality control, normalization, and quantification | Use standards not endogenous to sample; add at beginning of extraction for process monitoring [11] |

| Chromatography | UPLC BEH C18 columns, guard columns | High-resolution separation of metabolites prior to MS detection | Column temperature stability (±0.5°C) critical for retention time reproducibility [12] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Formic acid, ammonium formate | Mobile phase modifiers for improved ionization | 0.1% formic acid for positive mode; 10mM ammonium formate for negative mode [12] |

| Data Processing | Reference spectral libraries (HMDB, mzCloud) | Metabolite identification and annotation | Use multiple databases (HMDB, KEGG, LipidMaps) for comprehensive coverage [12] |

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The field of untargeted metabolomics continues to evolve rapidly, driven by technological advancements and growing recognition of its value in phenotype characterization. Several trends are shaping its future development:

- Technological Convergence: Integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with mass spectrometry data processing is transforming raw spectral data into actionable biological insights, reducing interpretation time and enhancing discovery potential [2].

- Multi-Omic Integration: Combining metabolomic data with genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic datasets provides systems-level understanding of biological processes and disease mechanisms [9] [10].

- Epidemiologic Scale Applications: Metabolic phenotyping is now being applied to large-scale population studies, enabling metabolome-wide association studies that capture information on dietary, xenobiotic, lifestyle, and genetic influences on health [10].

- Market and Infrastructure Growth: The untargeted metabolomics market is projected to grow from USD 494.50 million in 2024 to USD 1,093.34 million by 2032, reflecting increased adoption across academic, pharmaceutical, and clinical diagnostics sectors [2].

The metabolome indeed provides a direct signature of phenotype and biochemical activity, serving as the closest omics layer to functional outcomes. As untargeted metabolomics methodologies continue to mature and integrate with other technologies, they offer unprecedented opportunities to decode complex biological systems, discover novel biomarkers, and identify metabolic modulators of phenotype with significant potential for therapeutic intervention.

Untargeted metabolomics aims to provide a comprehensive, global analysis of all small-molecule metabolites within a biological system, offering a direct functional readout of cellular activity and physiological status [13] [11]. This field is a cornerstone of systems biology, enabling discoveries in disease mechanism elucidation, biomarker identification, and drug development [5]. The complexity and vast dynamic range of the metabolome mean that no single analytical technology can capture its entirety. Consequently, modern metabolomics relies on a synergistic, multi-platform approach. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS), and Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) constitute the three core technological platforms that provide complementary and comprehensive metabolomic coverage [14] [15] [16]. This technical guide details these platforms within the context of global metabolic profiling for discovery research, providing methodologies, comparisons, and practical resources for scientists.

Platform Comparison and Capabilities

The selection of an analytical platform is dictated by the specific research question, given the distinct advantages and limitations of each technology. The following table provides a summarized comparison of these core platforms.

Table 1: Core Analytical Platforms in Untargeted Metabolomics

| Feature | NMR | LC-MS | GC-MS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Principle | Detection of nuclei in a magnetic field | Chromatographic separation followed by mass-based detection | Chromatographic separation of volatilized metabolites followed by mass-based detection |

| Metabolite Coverage | Limited to tens to hundreds of metabolites; strong for sugars, amines, organic acids [14] [16] | Very broad; thousands of features; suitable for semi-polar and non-volatile compounds (e.g., lipids, secondary metabolites) [13] [17] | Broad for volatile or volatilizable compounds; hundreds of metabolites; strong for organic acids, amino acids, sugars, fatty acids [15] |

| Sensitivity | Low (μM range) [16] | High (pM-nM range) [13] | High (pM-nM range) |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal; often non-destructive; can use intact biofluids [14] [16] | Moderate to complex; requires metabolite extraction and protein precipitation [13] [18] | Complex; often requires derivatization to increase volatility [15] |

| Quantitation | Highly reproducible and absolute with a single internal standard or without [14] [16] | Relative quantitation is common; absolute quantitation requires specific internal standards [13] [17] | Excellent for absolute quantitation with internal standards; highly standardized [15] |

| Key Strengths | Non-destructive, highly reproducible, provides structural information, identifies novel metabolites, excellent for isotope flux studies [14] [16] | High sensitivity, broad metabolome coverage, can analyze labile compounds, no need for derivatization [13] [17] | Highly robust, reproducible, powerful spectral libraries for confident identification, considered a "gold standard" [15] |

| Primary Limitations | Low sensitivity, limited metabolite coverage due to spectral overlap [14] [16] | Ion suppression effects, requires method optimization (column, mobile phase), compound identification can be challenging [13] [4] | Limited to volatile/derivatizable metabolites, analysis time can be long, derivatization artifacts possible [15] |

Detailed Platform Methodologies

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

NMR spectroscopy is a highly reproducible and quantitative platform that excels in providing definitive structural elucidation of metabolites without the need for destruction or extensive preparation of the sample [14] [16].

Experimental Protocol for Biofluid Analysis (e.g., Serum, Urine):

- Sample Preparation: For biofluids like serum or plasma, a key step is the removal of macromolecules. This is efficiently achieved by ultrafiltration using molecular weight cut-off filters. This step minimizes signal broadening caused by protein binding, which can interfere with metabolites like TSP or DSS, making them unreliable as internal standards in intact biofluids [14]. The filtered sample is then mixed with a deuterated solvent (e.g., D₂O) for signal locking and a known concentration of a chemical shift reference, such as 3-(trimethylsilyl)-propionic acid-d4 sodium salt (TSP-d4) or DSS-d6, in a buffered solution to maintain consistent pH [14] [16].

- Data Acquisition: Standard one-dimensional (1D) ( ^1H ) NMR spectra are acquired using a pulse sequence with water suppression (e.g., presaturation) to reduce the intense water signal. For complex mixtures, two-dimensional (2D) experiments like ( ^1H )-( ^1H ) COSY (Correlation Spectroscopy) or ( ^1H )-( ^13C ) HSQC (Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence) may be employed to resolve overlapping peaks and assist in metabolite identification [14].

- Data Processing and Quantification: The free induction decay (FID) is subjected to Fourier transformation, phase correction, and baseline correction. Absolute quantification is performed by integrating the area of a target metabolite's resonance and comparing it to the integral of the internal standard's resonance (e.g., TSP), whose concentration is known. The concentration is calculated using the formula: ( C{met} = (I{met} / I{std}) \times (N{std} / N{met}) \times C{std} ), where ( C ) is concentration, ( I ) is the integral, and ( N ) is the number of protons contributing to the signal [16].

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS)

LC-MS is the workhorse of modern untargeted metabolomics due to its high sensitivity and expansive coverage of the metabolome. It couples the separation power of liquid chromatography with the detection power of mass spectrometry [13] [17].

Experimental Protocol for Global Profiling:

- Sample Collection and Metabolite Extraction: Rapid quenching of metabolism is critical for cell and tissue samples, typically using liquid nitrogen or cold methanol. A biphasic liquid-liquid extraction system, such as methanol-chloroform-water, is widely employed to simultaneously extract polar and non-polar metabolites [13]. For example, a common method uses a methanol:chloroform ratio of 2:1, followed by the addition of water to induce phase separation. Polar metabolites partition into the methanol-water phase, while lipids partition into the chloroform phase. Internal standards (e.g., stable isotope-labeled compounds) are added at the beginning of extraction to correct for technical variability [13] [18].

- LC-MS Analysis: Reversed-phase chromatography (e.g., C18 column) with a water-acetonitrile gradient containing 0.1% formic acid is standard for separating semi-polar metabolites. Mass spectrometry detection is typically performed using high-resolution mass analyzers (e.g., Q-TOF, Orbitrap) in both positive and negative electrospray ionization (ESI) modes to maximize metabolite coverage [13] [17]. Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA) or Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) methods are used to collect MS/MS fragmentation data for compound identification.

- Data Processing: Raw data processing involves peak detection, retention time alignment, and feature quantification using software tools like XCMS, MS-DIAL, MZmine, or integrated platforms like MetaboAnalystR 4.0 [11] [17]. This workflow converts raw data into a feature table of m/z, retention time, and intensity. Compound identification is achieved by matching accurate mass and MS/MS spectra against reference databases such as HMDB, MassBank, or GNPS [17].

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

GC-MS is a highly robust and standardized platform renowned for its excellent reproducibility and the availability of extensive, curated mass spectral libraries, making it a "gold standard" for identifying specific classes of metabolites [15].

Experimental Protocol for Primary Metabolite Profiling:

- Sample Derivatization: To make metabolites volatile, a two-step derivatization process is essential. First, methoximation is performed using methoxyamine hydrochloride in pyridine to protect carbonyl groups (e.g., in sugars). This is followed by silylation with a reagent like N-Methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (MSTFA), which replaces active hydrogens in functional groups (-OH, -COOH, -NH) with a trimethylsilyl (TMS) group [15].

- GC-MS Analysis: The derivatized sample is injected into a GC system equipped with a non-polar capillary column (e.g., DB-5MS). Metabolites are separated based on their volatility and interaction with the stationary phase as the oven temperature is ramped. The eluents are then ionized by electron impact (EI) at 70 eV, which produces rich, reproducible fragment patterns, and detected by a mass spectrometer [15].

- Data Processing and Identification: The acquired chromatograms are processed using AMDIS (Automated Mass Spectral Deconvolution and Identification System) or similar software for peak deconvolution. Deconvoluted mass spectra are then searched against commercial libraries (e.g., NIST, FiehnLib) that contain both mass spectra and retention index information, enabling a high level of confidence in metabolite identification [15].

The Untargeted Metabolomics Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the generalized logical workflow for an untargeted metabolomics study, integrating the three core platforms.

Untargeted Metabolomics Workflow

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of a metabolomics study depends on the use of specific, high-quality reagents and materials. The following table lists key items essential for the workflows described.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Metabolomics

| Reagent/Material | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., D₂O) | Provides a signal lock for NMR spectrometers and replaces exchangeable protons to avoid signal interference [16]. | NMR sample preparation for biofluids and tissue extracts. |

| Internal Standards (e.g., TSP-d4, DSS-d6) | Chemical shift reference and quantitation standard in NMR spectroscopy [14]. | Absolute quantitation of metabolites in an NMR sample. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (e.g., ¹³C-Phenylalanine) | Accounts for variability during sample preparation and analysis in MS; used for absolute quantitation [13] [18]. | Added at the beginning of metabolite extraction for LC-MS/GC-MS to correct for losses and ion suppression. |

| Methanol, Chloroform, Water | Forms a biphasic solvent system for comprehensive extraction of both polar and non-polar metabolites [13]. | Liquid-liquid extraction from cells or tissues (e.g., Folch or Bligh & Dyer method). |

| Derivatization Reagents (e.g., MSTFA, Methoxyamine) | Increases volatility and thermal stability of metabolites for GC-MS analysis [15]. | Two-step derivatization of polar metabolites (organic acids, sugars, amino acids) prior to GC-MS injection. |

| Protein Precipitation Solvents (e.g., Acetonitrile, Methanol) | Removes proteins from biofluids to prevent column fouling and ion suppression in LC-MS [13] [18]. | Preparation of plasma or serum samples for untargeted LC-MS profiling. |

The triumvirate of NMR, LC-MS, and GC-MS provides a powerful, complementary toolkit for comprehensive coverage of the metabolome in untargeted discovery research. NMR offers unparalleled quantitative robustness and structural elucidation, LC-MS delivers extensive coverage and high sensitivity, and GC-MS provides highly reproducible analyte identification. The convergence of data from these platforms, supported by robust experimental protocols and advanced bioinformatics tools, enables researchers to construct a deep and holistic understanding of metabolic phenotypes, thereby accelerating discovery in basic research and drug development.

Untargeted metabolomics is a powerful, hypothesis-free approach that measures the complete set of small-molecule metabolites in a biological sample, providing a comprehensive view of metabolic status. This methodology has emerged as a crucial tool in systems biology, capturing the functional outcome of complex cellular processes by analyzing metabolites with molecular masses typically under 1500 Da [19]. As the final downstream product of cellular regulation and response, the metabolome offers a unique window into phenotypic expression that closely reflects the functional state of biological systems, often more directly than genomics, transcriptomics, or proteomics [20]. The position of metabolomics at the end of the 'omics cascade enables researchers to observe the integrated response of organisms to genetic variation, environmental challenges, disease processes, and therapeutic interventions [21] [19].

The fundamental strength of untargeted metabolomics lies in its ability to simultaneously detect both known and novel metabolites without prior selection, making it exceptionally valuable for discovery-driven research [22]. By employing high-resolution analytical platforms—primarily liquid or gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC-MS/GC-MS)—this approach can detect thousands of metabolite signals from minimal sample volumes, enabling researchers to identify novel biomarkers and uncover unexpected metabolic changes [1]. This capability positions untargeted metabolomics as an essential technology for bridging basic scientific discovery with translational medical applications, from early-stage biomarker identification to elucidating mechanisms of drug action [21] [19].

Analytical Frameworks and Workflows

Core Technical Workflow

The untargeted metabolomics workflow follows a structured, multi-stage process designed to transform raw biological samples into biologically interpretable data. This workflow encompasses experimental design, sample preparation, data acquisition, processing, statistical analysis, metabolite identification, and biological interpretation [22]. Each stage requires specific technical considerations and quality control measures to ensure generated data accurately reflects the biological system under investigation rather than technical artifacts.

A standardized workflow is critical for obtaining reliable and reproducible results. The process begins with careful experimental design that defines sample size, control groups, and experimental conditions to ensure adequate statistical power while minimizing variability [22] [20]. Next, sample collection and preparation must be optimized for specific sample types (tissues, biofluids, cells) using appropriate extraction solvents like methanol or acetonitrile to isolate metabolites while preserving their structural integrity [22]. Consistency at this stage is vital to reduce technical noise and ensure data reflects true biological differences. Data acquisition then utilizes advanced analytical techniques, with LC-MS being particularly valued for its sensitivity and ability to analyze polar and semi-polar metabolites, while GC-MS excels for volatile compounds and NMR provides detailed structural information [22].

The subsequent data processing stage transforms spectral data into analyzable formats through peak identification, alignment across samples, and normalization to adjust for systematic biases [22]. Statistical analysis employs both univariate methods (t-tests, ANOVA) to identify individual metabolite changes and multivariate approaches (PCA, PLS-DA) to explore data structure and classify sample groups [22]. Finally, metabolite identification matches spectral data against curated databases (mzCloud, METLIN, HMDB), while biological interpretation maps identified metabolites to pathways using resources like KEGG to understand their functional roles [22].

Statistical Approaches and Data Visualization

Robust statistical analysis is particularly crucial for untargeted metabolomics due to the high-dimensional nature of the data, where the number of metabolite variables often exceeds sample numbers. Comparative studies have revealed that statistical method performance depends on dataset characteristics, with sparse multivariate methods like Sparse Partial Least Squares (SPLS) and Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) demonstrating superior performance in scenarios where metabolite numbers are large or sample sizes are limited [23]. These approaches excel at variable selection and maintain favorable operating characteristics by effectively handling the intercorrelations common in metabolomic data [23].

In contrast, traditional univariate methods with multiplicity correction (e.g., FDR) show limitations with increasing sample sizes due to their susceptibility to identifying false positive associations through correlation with true positive metabolites [23]. The choice between continuous and binary outcomes also influences statistical performance, with binary outcomes presenting greater analytical challenges, particularly in smaller sample sizes [23].

Effective data visualization represents another critical component throughout the analytical workflow, serving as a bridge between complex data and biological interpretation. Visualizations facilitate data inspection, evaluation, and sharing at every stage, from assessing data quality to presenting final results [4]. Modern visualization strategies incorporate interactivity, allowing researchers to explore data from multiple perspectives without manually regenerating plots. These approaches extend human cognitive abilities by translating complex data into accessible visual channels through scatter plots, cluster heatmaps, and network visualizations [4]. The field of information visualization (InfoVis) specifically studies how to optimize these processes for knowledge generation through interactive visualizations tailored to domain-specific goals [4].

Key Research Applications

Biomarker Discovery and Disease Mechanism Elucidation

Untargeted metabolomics has revolutionized biomarker discovery by enabling comprehensive profiling of metabolic alterations associated with disease states. This approach identifies metabolite signatures that serve as early indicators of pathological dysfunction prior to clinical disease manifestation [19]. The proximity of metabolites to phenotypic expression makes them particularly valuable for predicting diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment monitoring across diverse conditions [19]. Successful applications span cancer, metabolic disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, and cardiovascular conditions, where metabolomic profiling has revealed previously unrecognized biochemical pathways involved in disease pathogenesis [21] [19].

In cancer research, untargeted metabolomics has uncovered metabolic reprogramming in tumor cells, including alterations in energy metabolism, nucleotide biosynthesis, and lipid metabolism that support rapid proliferation [19]. These findings provide both diagnostic biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets for intervention. Similarly, in metabolic disorders like diabetes and obesity, metabolomic studies have identified specific metabolite patterns associated with disease risk and progression, offering insights into underlying mechanisms beyond traditional clinical markers [21] [23]. The ability to profile thousands of metabolites simultaneously from minimal sample volumes makes untargeted approaches particularly valuable for rare diseases or conditions where conventional biomarkers lack sufficient sensitivity or specificity [1].

Drug Development and Pharmacology

In pharmaceutical research, untargeted metabolomics provides powerful approaches for evaluating drug efficacy, toxicity, and mechanisms of action. By capturing global metabolic shifts in response to drug exposure, researchers can identify both intended and off-target effects, supporting more comprehensive safety and efficacy profiling [1]. This application spans preclinical development through clinical trials, where metabolomic analysis of blood, tissue, or urine samples reveals how drug interventions alter metabolic pathways in living systems [1] [19].

A key advantage in pharmacology is the ability to identify metabolic signatures that predict individual variation in drug response, advancing the goals of personalized medicine [21]. Untargeted approaches can uncover novel metabolite-drug interactions that might be missed in targeted analyses, potentially explaining unexpected efficacy or toxicity profiles [19]. The technology also facilitates drug repositioning by revealing similarities between metabolic effects of established drugs and new chemical entities, potentially identifying new therapeutic applications for existing compounds [19]. Furthermore, the ability to monitor metabolic changes over time provides dynamic information about treatment response, enabling earlier assessment of therapeutic effectiveness than conventional endpoints [19].

Nutritional Science and Environmental Health

Untargeted metabolomics has emerged as a transformative tool in nutritional science, where it helps decipher the complex relationships between diet, metabolism, and health outcomes. By profiling metabolic responses to dietary interventions, researchers can identify biomarkers of nutrient intake, assess bioefficacy of nutritional compounds, and understand individual variation in response to specific dietary patterns [1]. This application extends to animal health and nutrition, where metabolomic analysis of serum, tissue, feces, and milk enables monitoring of growth, immunity, and overall health status to optimize feeding strategies and improve welfare [1].

In environmental health, untargeted metabolomics detects metabolic dysregulation in organisms exposed to pollutants, providing sensitive indicators of environmental stress and toxicity mechanisms [22]. Studies applying GC-MS to aquatic organisms exposed to industrial contaminants have revealed altered fatty acid profiles and other metabolic stress markers that serve as early warning systems for environmental contamination [22]. This approach offers insights into the biochemical pathways affected by environmental exposures, helping establish causal relationships between contaminants and biological effects while identifying potential intervention points to mitigate adverse health outcomes [22].

Table 1: Research Applications of Untargeted Metabolomics

| Research Area | Key Applications | Sample Types | Representative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Biomarker Discovery | Early diagnosis, patient stratification, prognostic assessment | Plasma, serum, tissue, urine | Identification of metabolic signatures for cancer, diabetes, neurodegenerative diseases [19] |

| Drug Development | Mechanism of action, toxicity assessment, treatment response | Biofluids, cell cultures, tissues | Comprehensive evaluation of drug-induced metabolic changes [1] |

| Nutritional Science | Dietary biomarker discovery, nutrient bioefficacy, metabolic phenotype | Serum, feces, urine | Metabolic signatures of healthy diets and specific nutrients [22] |

| Environmental Health | Toxicity mechanism, exposure assessment, ecological monitoring | Aquatic organisms, soil, water | Altered fatty acid profiles in pollutant-exposed organisms [22] |

| Microbiome Research | Host-microbe interactions, microbial metabolism, therapeutic monitoring | Feces, gut content, biofluids | Microbial-derived metabolites influencing host physiology [1] |

Translational Pathways and Clinical Implementation

From Discovery to Clinical Applications

The translation of untargeted metabolomics discoveries into clinically applicable tools faces several challenges that must be systematically addressed. While metabolomics studies have produced significant breakthroughs in biomarker discovery and pathway characterization, the implementation of these research outcomes into clinical tests and user-friendly interfaces has been hindered by multiple factors [21]. These include the need for robust validation of candidate biomarkers, standardization of analytical protocols across laboratories, and demonstration of clinical utility beyond established diagnostic markers [21] [20]. Successful translation requires moving from initial discovery in controlled research settings to validation in larger, more diverse patient populations, ultimately leading to clinically implemented tests that inform medical decision-making.

The evolution of other omics fields provides instructive models for metabolomics translation. Genomics has achieved the most substantial translational success, with nearly 75,000 genetic tests reportedly available by 2017, particularly in prenatal testing and hereditary cancer risk assessment [21]. In contrast, proteomics and transcriptomics have seen more limited clinical implementation, with only one proteomic assay and five transcriptomics assays translated into clinical settings as of 2018 [21]. This disparity highlights both the maturity of genomics and the additional complexities involved in translating dynamic molecular measures like metabolites that fluctuate in response to numerous environmental and physiological factors [21].

Implementation Challenges and Solutions

Several specific challenges impede the translational progress of untargeted metabolomics. Analytical variability stemming from different instrumentation, protocols, and data processing methods can limit reproducibility across sites [20]. Biological interpretation of complex metabolomic data remains difficult due to incomplete knowledge of metabolic pathways and the influence of multiple confounding factors on metabolite levels [20]. Additionally, the correlational nature of many untargeted discoveries requires extensive follow-up studies to establish causal relationships and mechanistic insights [21] [19].

Addressing these challenges requires coordinated efforts across multiple domains. Standardization of experimental procedures, particularly for cell culture metabolomics where external variables can be better controlled, provides a foundation for reproducible results [20]. Implementation of rigorous quality control systems incorporating blanks, solvents, pooled quality controls, and internal standards ensures data accuracy and batch comparability [1]. For biological interpretation, integration with other omics data (genomics, proteomics, transcriptomics) through systems biology approaches provides more comprehensive insights into the regulatory networks underlying observed metabolic changes [21] [19]. Finally, developing clear reporting standards and validation frameworks similar to those established for genomics (e.g., Institute of Medicine guidelines for omics-based tests) will strengthen the evidence required for clinical adoption [21].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Untargeted Metabolomics

| Reagent/Platform Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Systems | Liquid Chromatography (LC), Gas Chromatography (GC) | Separation of complex metabolite mixtures | LC for polar/semi-polar metabolites; GC for volatile compounds [22] |

| Mass Spectrometry Platforms | Orbitrap, Q-TOF, Triple Quadrupole | Metabolite detection and quantification | High-resolution accurate mass (HRAM) instruments for precise identification [22] |

| Metabolite Databases | mzCloud, METLIN, HMDB, NIST | Metabolite identification and annotation | Spectral matching for compound identification [22] |

| Extraction Solvents | Methanol, Acetonitrile, Chloroform | Metabolite isolation from biological samples | Solvent systems tailored to sample type and metabolite classes [22] |

| Pathway Analysis Resources | KEGG, MetaCyc, MetaboAnalyst | Biological interpretation and pathway mapping | Contextualizing metabolites within biochemical pathways [22] |

| Quality Control Materials | Internal standards, pooled QC samples, reference materials | Monitoring analytical performance and reproducibility | Ensuring data quality throughout workflow [1] |

Future Directions and Emerging Applications

Technological Advancements and Integration Opportunities

The future trajectory of untargeted metabolomics points toward several promising technological developments that will expand its applications across biological research. Mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) technologies now enable simultaneous visualization of spatial distribution for small metabolite molecules within tissues, providing unprecedented insights into metabolic heterogeneity in pathological conditions like cancer [19]. Single-cell metabolomics has become increasingly feasible with sensitivity improvements in instrumentation, allowing researchers to investigate metabolic variation at cellular resolution and uncover previously masked heterogeneity in cell populations [20]. Additionally, advancements in computational tools and artificial intelligence are enhancing metabolite identification, particularly for novel compounds not present in existing databases [1] [22].

Integration with other omics technologies represents another significant direction, creating multi-dimensional datasets that offer more comprehensive views of biological systems. Combining metabolomics with genomics helps connect genetic variation to metabolic phenotypes, while integration with proteomics and transcriptomics reveals how molecular regulatory networks translate into functional metabolic outcomes [21] [19]. Such integrated approaches are particularly valuable for elucidating complex disease mechanisms and identifying therapeutic targets within disrupted biochemical pathways [19]. The growing emphasis on personalized medicine and nutrition further drives the need for metabolic phenotyping that can account for individual variation in response to treatments, diets, and environmental exposures [21].

Expanding Translational Impact

The translational potential of untargeted metabolomics continues to expand beyond traditional clinical applications into diverse fields including agriculture, environmental science, and biotechnology. In agricultural research, untargeted metabolomics approaches have been applied to characterize cereals and derived products, uncovering metabolic profiles linked to drought resistance and nutritional quality that can guide crop improvement strategies [22]. In environmental science, metabolic profiling of organisms exposed to pollutants provides sensitive indicators of ecosystem health and reveals mechanisms of toxicity [22]. Microbiome research represents another growing application, where untargeted metabolomics helps decipher metabolic interactions between hosts and their microbial communities, elucidating how gut microbiota influence host physiology and contribute to health and disease [1].